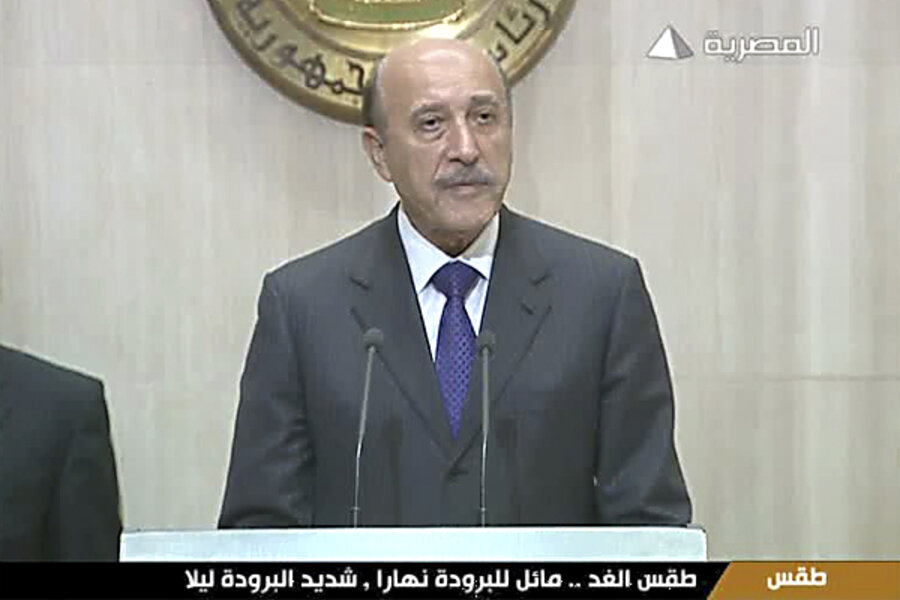

Egypt crisis: What role will Omar Suleiman play?

Loading...

| Boston

Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak today said he was apportioning a measure of power to his vice president, Omar Suleiman, in his latest attempt to quell weeks of demands for his resignation from protesters and growing pressure from Western governments. But debate is swirling over exactly how much authority he is ceding to his vice president.

Mr. Mubarak proclaimed in a TV address – in which many had expected him to announce his resignation – that he was staying at the helm until elections in September and would "not accept or listen to any foreign interventions or dictations."

Many among the crowds at central Cairo's Tahrir Square were skeptical of any regime effort to mollify protesters without delivering real change in the form of Mubarak stepping down.

“I think they’re just playing for time, and I’m worried that they’re setting the stage for the military to suddenly strike at us,” says Mohammed Hawas, a businessman who ran for president in 2005 and seeks to run again in September elections. “None of us should go home before the regime is swept away.”

While reports had swirled ahead of the speech that Mr. Suleiman would be taking Mubarak's place to lead the country through a political transition, the announcement tonight potentially sets Mubarak on a collision course with angry protesters.

"The stage is set for a tragedy," says US Army Col. (Ret.) W. Patrick Lang, a former senior official at the Defense Intelligence Agency who was based in the Middle East.

Mubarak sees himself 'as the state'

After Mubarak's speech, Egypt's ambassador to the US, Sameh Shoukry, told CNN that Mr. Suleiman was now the "de facto" president: "President Mubarak transferred the powers of his presidency to his vice president." He added that Mubarak was the "de jure" president only.

Pressed as to whether Mubarak now had no powers, Mr. Shoukry said: "That is an interpretation you can make."

Lang says there is no reason not to take the ambassador's statements at face value. "In the dim murky world of Egypt’s culture and politics, what is sought here is a way for Mubarak to save face," he says. But, he adds, Mubarak has "thrown down the challenge to what is now a revolutionary movement."

Analysts say that Mubarak apparently has the backing of the popular Army and the respected Suleiman, whose Jan. 29 appointment as vice president was seen as a first step toward the end of Mubarak's rule. Now, that transition is in doubt, with Suleiman adding in a speech following Mubarak's that the protesters in Cairo's Tahrir Square should "go home."

“I call upon the young people, the heroes of Egypt: Go back to your houses, go back to your work,” said Suleiman in a short televised address. “The homeland needs your work.”

With those words, many hopes died that Suleiman might lead the country into elections.

"This negates whatever impact [Sulieman] might have had," says Mr. Lang, adding that this in itself is a loss for Egypt.

Who is Suleiman?

Born to a humble family in Qena on July 2, 1936, Suleiman attended Egypt’s military academy, trained in the former Soviet Union, and studied political science at Cairo University and at Ain Shams University in Cairo. Before being appointed vice president, Suleiman had long held the posts of chief of the General Intelligence Service, director of military intelligence, and deputy head of military intelligence.

In 1995, Suleiman famously insisted that Mubarak's armored limousine be flown with them for a conference in Ethiopia, likely saving the president's life when their vehicle came under gunfire during an assassination attempt. Foreign Policy magazine in 2009 proclaimed him the most powerful spy in the Middle East.

"This is a guy that Mubarak took up on the basis of his supreme competence," says Lang, who first met Suleiman in 1987 while working as the Pentagon's Defense Intelligence Officer for the Middle East and has maintained ties with him. He recalls their first meeting in Cairo, seated opposite one another at a palace conference and dining together every night.

"He is a very humorous guy. A dry, witty sort of person," says Lang. He describes Suleiman as considerate, willing to listen to subordinates, and the most capable man in the current government.

A man for all seasons

Over the years, the stress of working under President Mubarak has taken its toll.

"Working for Hosni Mubarak is the kind of job where you sit at a desk waiting for the red phone to ring," Lang says, noting that even Suleiman fears the president. “Off with your head is not an exaggeration,” he adds.

"Mubarak is Pharaoh in his own mind. He’s laughingly referred to as Pharaoh all over the Arab world. I don’t think this guy [Suleiman] sees himself that way at all. I think he would see himself as public servant who would take the country toward elections," Lang says.

Lang argues that Suleiman would not have the stamina or the desire to become Egypt's next president. He adds, however, that Suleiman "is also not afraid to use force to put the country in order."

Having come from the military, like all Egyptian leaders since 1952, along with his tough stances on Hamas, Iran, and political Islamism, make him a popular choice with the armed forces in Egypt and the governments in Israel and US.

According to a US diplomatic cable dated May 14, 2007, titled "Presidential Succession in Egypt" and released in December by WikiLeaks, Suleiman was being groomed for succession:

"Egyptian intelligence chief and Mubarak consigliere, in past years Soliman was often cited as likely to be named to the long-vacant vice-presidential post. In the past two years, Soliman has stepped out of the shadows, and allowed himself to be photographed, and his meetings with foreign leaders reported. Many of our contacts believe that Soliman, because of his military background, would at least have to figure in any succession scenario."

But would Suleiman be good enough?

While Suleiman has no time for hobbies, according to Lang, he is a voracious reader, especially of the works of Ernest Hemingway. "He's probably read everything that Hemingway ever wrote," says Lang.

And now, with Mubarak increasingly under pressure to step down, eyes are looking to him as the man who will be tasked with keeping Egypt afloat amid a sea of public unrest and demands for political reforms.

But for tens of thousands of protesters in Tahrir Square, it’s not just Mubarak who is the problem – it’s his whole regime, including stalwarts like Suleiman.

“Yes, it’s Mubarak, but it’s the system, too,” says Ahmed Dadr, a soft-spoken student who said he was exhausted from participating in street battles with the police. “Getting rid of Mubarak and keeping the system means the revolution hasn’t succeeded.”

Staff writer Dan Murphy contributed reporting from Cairo.