Fearing boycott, Israeli academics warn against accrediting West Bank school

| Ariel, West Bank

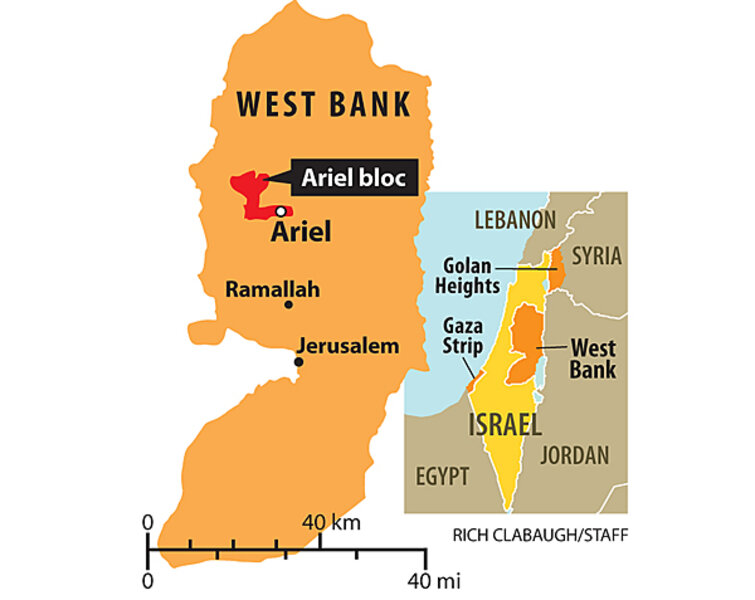

Perched on a hilltop range in the northern West Bank, the Ariel University Center (AUC) looks west toward the Tel Aviv skyline 20 miles away and north to the minarets of Palestinian villages a few miles off.

The ivory tower has sprouted up amid the red-roofed settler homes and olive tree groves at the edge of Ariel. In between classes, stylishly dressed students stretch out on manicured lawns shaded by pines. It's a cutting-edge place, too: A promotional video touts an optical laboratory that tests non-invasive surgical tools while academic officials brag about a laser project and students talk about their research on water desalinization.

Built up over 15 years, the facilities, professors, and research are central to AUC's next goal: becoming Israel's eighth accredited university.

That would be a milestone for both the school and Ariel. It would bestow a new kind of national gravitas on the settlement, the fourth largest in the West Bank, making it more difficult to uproot in the case of a peace agreement with the Palestinians.

Political and academic officials have not been shy about that secondary goal. In AUC's promotional video, Strategic Affairs Minister Moshe Yaalon praises the school: "With its strategic location, [AUC] enables defensible borders for the state of Israel."

That's why what would likely be a simple accreditation process in almost any other country has instead become a controversial political decision. The question of whether to make AUC official raises explosive questions about Israel's long-term military occupation of the West Bank.

Now, after Israel's committee on higher education in the West Bank formally upgraded the university, concern is growing that such a move could fuel international efforts to boycott Israel, particularly its academic community, which often finds itself viewed by international colleagues as a proxy for the Israeli government. Accreditation of a university in the West Bank, they say, may be one step too far.

"It's a strategic threat to the state," said Hebrew University President Menahem Ben-Sasson, according to Israeli news outlets. "We are putting the next Nobel Prize in danger."

Fair protest or delegitimization?

Since the second intifada and the collapse of the Oslo peace process more than a decade ago, Israel has faced efforts by Palestinian solidarity activists to promote an international boycott of Israeli professors, companies, and concerts because of their alleged association with Israeli government policies.

Palestinians and their supporters say the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel, intended to persuade the Jewish state to end more than four decades of military occupation in the West Bank and to remove settlements, is a legitimate form of political pressure.

But even though some boycott proponents say they are solely focused on settlement activity considered illegal by the international community, many supporters of Israel consider boycotts part of a broader campaign to delegitimize Israel's right to exist.

Organized efforts at a boycott of Israeli academia started in 2002 in Britain, when a pair of Israeli language experts from universities inside Israel were dismissed from the editorial board of a British journal on translation studies.

Other universities have been dragged into the debate. In 2005, Jonathan Rynhold, a Bar-Ilan University political science professor, led a delegation of Israeli academics on a trip to Britain to help defeat a motion at the national Association of University Teachers that would have boycotted Haifa University for trying to censure a revisionist historian and Bar-Ilan University for operating classes on the Ariel campus, which was initially an outgrowth of Bar-Ilan.

Mr. Rynhold, who says he opposes academic boycotts in principle, says the core supporters of BDS would seek a boycott against Israel regardless of its policies in the West Bank. But he also says AUC's accreditation would hurt the work of Israeli professors because it would bolster boycott advocates' message among moderates.

"The ability of these people to gain wider sympathy depends on resonating with more liberally minded people. There's no doubt in my mind that by making Ariel a university, this is bad news for the antiboycott movement," Rynhold says. "It makes [the anti-boycott] case much more difficult to make."

The move to accredit AUC comes as support for a commercial boycott of Israeli companies with activities in the West Bank is growing. South Africa's ministry of trade recently announced that it would insist on special labeling for Israeli products from the West Bank – they are currently marked "Made in Israel" – to give consumers the option of avoiding the purchase of settlement goods.

In April, The Co-operative Group, Britain's No. 5 food retailer, said it would end trade with companies that export produce from Israeli settlements. Earlier this month, European Union members got a legal opinion stating they could legally ban trade with the settlements. Efforts at the Park Slope Food Coop in Brooklyn, N.Y., to ban Israeli goods from the shelves were ultimately rejected, but only after a bitter battle.

Though the South African boycott provoked an angry response from the Israeli government, one former top official expressed support. Alon Liel, who served as Israeli ambassador to South Africa and foreign ministry director general, wrote in a commentary this month for South Africa's Business Day that he supported the South African decision as a "small but symbolic" protest "that holds a mirror up to Israeli society."

While a few companies, such as lockmaker Mul-T-Lock Ltd., have relocated from West Bank industrial zones to factories inside Israel, the trade boycott efforts have had a negligible impact on the overall economy, say Israeli officials.

"In the big picture it hasn't yet impacted Israel," says Paul Hirschhorn, a spokesman for the foreign ministry. "Culturally and economically, Israel continues to be a remarkably successful venture."

Academic community wrings its hands

The same can be said for Israel's seven public universities, many of which enjoy world-class reputations. Last month, the presidents of those institutions published an open letter to the government suggesting that accrediting AUC would cannibalize already strained higher education budgets.

An eighth university "would lead to a mortal injury to the higher education system in Israel," the letter read. "There is no real need for an additional university in Israel."

A petition of 1,000 academics was more political, warning of an end to international academic cooperation.

"There is already a selective academic boycott in place: Researchers at Ariel are unable to submit grant requests at many funds around the world.… The identification of the entire Israeli academy with the settlement policy will put it in danger."

Supporters of the school in Ariel, however, say the opposition is politically motivated. "It's the leftists that are pulling the strings," says Hila Vaknin, a marketing student from Jerusalem, on a break between classes at AUC.

Talking about the decision and the resistance by Israeli academics sends Eldad Halachmi, AUC's gregarious vice president for development, into a frustrated rant.

On Mr. Halachmi's desk is an architectural rendition of a modern Jewish cultural center and synagogue for prospective donors. Just outside his office, a crane looms over the building site of a future library. Uncertainty about AUC's status is hurting his fundraising effort, he complains.

He alleges that many of the Israeli academics who warn of a boycott have a political ax to grind against Ariel and support a boycott of the settlements among Israelis.

"They are riding this horse because they know it's very PC in the world … that everything over the Green Line is a terrible thing," Halachmi says, referring to the 1949 cease-fire line separating the West Bank and Israel. According to officials, 85 percent of the 13,000 students hail from inside Israel.

Halachmi says that AUC participates in "dozens, if not hundreds" of instances of academic collaboration. But it is ineligible for money from Israel-US funds that promote joint research because of its location in a Jewish settlement, considered illegal by most of the international community.

Earlier this month, a funding committee of Israel's Committee on Higher Education ruled that a decision on accreditation should be postponed a year to allow time to determine whether there's a need in Israel for an eighth university.

The postponement is seen as a politically driven attempt to buy time to gain opposition to accreditation, although that hasn't eliminated the possibility that politicians in the right-leaning governing coalition may intervene on AUC's behalf.

However, the Committee on Higher Education in Judea and Samaria (the Jewish biblical name for the West Bank, often used by settlers and their supporters), which has the formal authority to establish a university in the West Bank, decided today to accredit Ariel anyway.

'Like blaming the University of California for… Iraq'

The battle over AUC highlights how Ariel, possibly more than any other settlement, has sought to establish itself as a normal Israeli bedroom community, complete with industrial parks, manicured lawns, and a performing arts center.

Perhaps for that reason, the city of Ariel has recently been the target of boycott efforts by Israel's far left. Two years ago, a group of actors from the national theater company Habima stirred up controversy when they refused to perform in Ariel. A group of left-wing Israeli academics refused to work with AUC and called on students and staff to leave.

Paul Frosh, a Hebrew University communications professor who was active in the antiboycott movement, says AUC's accreditation would undercut efforts by Israeli universities to separate themselves from the government's West Bank settlement policy.

For now, pinning blame on the universities is "like blaming the University of California for any American actions in Iraq or Afghanistan," Mr. Frosh says.

But that argument would gain traction if AUC is accredited.

"Once you make the college of Ariel a full-fledged university, you basically say that higher education authority is not autonomous from the Israeli government, and it is directly supporting the occupation," Frosh says.

For now, however, the main damage to Israel from the BDS campaign seems to be a stubborn public relations stain. Almost every major musical artist who visits Israel faces pressure to cancel performances, and many Israeli performance troupes traveling abroad risk running into boycott protests.

Earlier this year, jazz vocalist Cassandra Wilson canceled a visit to Israel just days before a scheduled appearance, and novelist Alice Walker refused to have her book "The Color Purple" translated into Hebrew for a new edition.

Israel and its supporters abroad remain vigilant of actions that could boost the BDS movement. A musical performer canceling a Tel Aviv concert is one thing, but the campaign could eventually extend to more critical areas like trade and academia.

"There's always a concern," says a Western diplomat here who has followed boycott efforts. "They're worried it could develop into something in the future."