Israeli Oscar contenders force citizens to confront uncomfortable questions

Loading...

| Jerusalem

A former spy chief is making gripping statements about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but at Jerusalem’s chic Cinamatheque, two university students can’t keep their eyes on the screen. One sends text messages and checks Facebook; the other shifts uneasily.

“I felt uncomfortable in my chair,” says one of them, Shay Amiran, a former combat soldier, after the screening of Oscar-nominated “The Gatekeepers.” He especially bristled at a comparison between Israel and Nazi Germany during World War II.

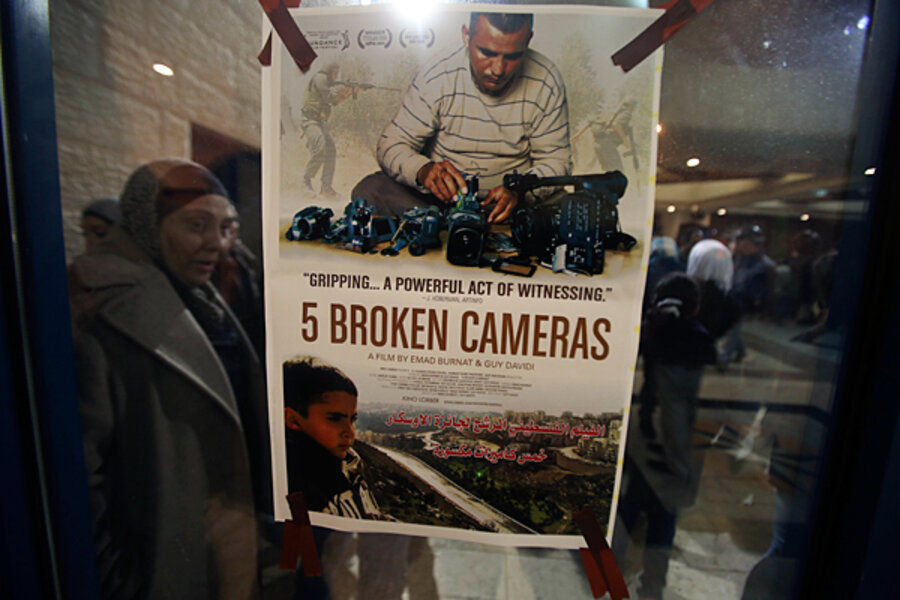

“The Gatekeepers,” which interviews six former heads of Israel’s Shin Bet intelligence agency, along with “5 Broken Cameras,” which captures a Palestinian family’s life amid protests against construction of Israel’s separation wall, are the first Israeli-funded films to receive Academy Award nominations for best documentary since 1975. While winning international acclaim, the movies are riling people on both sides of the political aisle in Israel – from those who see them as government-funded “self-flagellation” to those who see the movies as raising crucial issues that the Israeli public and government are unwilling to address.

“It’s an incredible achievement for the Israeli film industry,” says Amy Kronish, an Israeli film critic. “Both of these films deal with issues that are not being grappled or tackled by the Israelis at this time.”

While the movies were initially pigeonholed as boutique films that would draw only a fraction of Israelis, “The Gatekeepers” recently became the first documentary to be shown in commercial theaters in Israel and is the second-highest grossing Israeli film of the year.

The overriding message of the films, which both received indirect government funding through subsidies to the Israeli film industry, is that the status quo in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is unsustainable. What sets them apart from the many other films on the topic is the rarity of the voices that share the message: Israelis from the heart of the defense establishment in “The Gatekeepers” and a young Palestinian boy in “5 Broken Cameras.”

In the opening scene of “5 Broken Cameras,” Palestinian Emad Burnat, who shot the footage and co-directed the movie, describes the birth of his children as symbolizing different phases of the conflict. His first son was born, he says, “in the optimism of Oslo,” his second at the start of the second intifada. His third son, Gibreel, was born in 2005 at the same time his village began protests against construction of the Israeli separation barrier through their farmland.

The movie captures Gibreel’s first words: “wall” and “soldiers.”

In “The Gatekeepers” all six former heads of Shin Bet call, in varying degrees, for collaboration with Palestinians. Sitting calmly in suspenders or polo shirts, the former chiefs reflect on the moral dilemmas they faced, such as deciding whether to drop a one-ton bomb on a Gaza militant if it meant others in the neighborhood would be killed.

The movie portrays the ex-chiefs as questioning whether they succeeded at a tactical level, but lacked a broader strategy to bring lasting peace.

“We’re winning all the battles,” says Ami Ayalon, Shin Bet chief from 1996 to 2000, in the movie. “And we’re losing the war.”

'Occupation' should end

The directors and their supporters say that Israel’s policies toward the Palestinian territories are ultimately undermining the longevity of the Jewish state.

Dror Moreh, director of “The Gatekeepers,” says he intended his film for Israelis plus an international audience that would exert pressure on the Israeli government.

“I wanted this movie to change things, to stir up debate, to stir up beliefs and to challenge people who believe in one thing,” he says. “The message [is] that the occupation of the West Bank is bad for the safety and security of Israel.”

Guy Davidi, the Israeli co-director of “5 Broken Cameras,” also believes pressure should come from Israeli society and abroad if government policies are to change.

“I don’t believe that change comes from just inside, or just outside,” he says. “It’s natural to want pressure from other countries to stop occupation because from my point of view stopping occupation is something good for Israel.”

For some Israelis, however, the films present an incomplete portrait of a complex conflict. Some see them as part of a broader asymmetry, in which the international community focuses disproportionately on Israeli missteps without regard to transgressions by Palestinians – like in the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign, which seeks to penalize Israel financially and isolate it internationally for its policies toward the Palestinian territories.

“While the films are well-made, we can suspect that their nomination does not stem from international recognition of the Jewish state’s filmmaking abilities, but from an international obsession with shaming it,” wrote opinion columnist Hagai Segal in Israel’s YNet News.

There’s also a sense that those abroad are overly critical of Israel without understanding the security concerns of its citizens, many of whom have had to contend with violence in their daily lives – whether through army service, suicide bombings, or rocket attacks.

Indeed, security is of top concern for Mr. Amiran and his friend Hila, who went to the Jerusalem Cinamatheque screening of “The Gatekeepers” out of curiosity from the Oscar buzz. Their view is shaped by personal loss and a distrust of Palestinian desire for peace, which they believe was discredited by the outbreak of the second intifada after a peace offer by former Prime Minister Ehud Barak.

“If you want to talk about morality, you have no justification for killing kids, teenagers,” says Hila, whose friend was killed in 2001 in an attack on a cafe when she was 15.