Poor and vulnerable, Syrian refugee families push girls into early marriage

Loading...

| Amman, Jordan

Sara has stopped listening to news from her hometown, Homs, one of the most heavily bombarded cities in Syria’s civil war. Instead, the 17-year-old waits for word of her husband, Fuad, a Saudi national 25 years her senior.

Last October, Fuad paid her family a hefty dowry of 4,000 Jordanian Dinars ($5,600). He then brought her from the sprawling Zaatari refugee camp near the Syrian border to live with him in the capital, Amman. After their desperate flight from Syria, a better life, he promised, awaited her and her family in Saudi Arabia.

But after just a month and half, Fuad left without a word, disconnected his Jordanian cellphone, and left the family “alone here, suffering poverty and neglect,” says Sara’s mother, Arij.

Since the Syrian conflict began in March 2011, more than 1.2 million refugees have poured into neighboring countries, of whom 70 percent are women and children, according to UN estimates. Also showing up in refugee centers: Arab men on the hunt for child brides.

Aid workers and refugees say that vulnerable teenage women are at risk of sexual exploitation under the pretense of marriage. These marriages are often not consensual, lack legal standing, and can lead to abandonment–as in Sara’s case–or far worse outcomes, including forced prostitution.

But, as the war rages on in Syria, many displaced families have married off their daughters early, either in the belief that it can protect them from rape, or to “cover” the disgrace of past sexual abuse both during the conflict and in the camps.

Early marriage, as young as 14, is common in rural Syria, where many of Jordan’s refugees hail from. However, the average age has slightly dropped since their arrival, according to a UN Women survey. With that drop, comes higher risk for sexual abuse, experts say.

In Syria, rape has been used as a weapon of war to terrorize civilians, says Lauren Wolfe, director of Women under Siege, an organization in New York that maps sexual violence in Syria. In a report released in January by the International Rescue Committee, refugees in Jordan and Lebanon cited the fear of public armed assault or gang rape, often staged in front of family members, as their primary reason for fleeing.

“There’s so much stress, and a lot of that violence is coming out toward women,” says Ms. Wolfe. She says that high levels of sexual violence and exploitation exist in Syria, and refugees are facing the threat once again in camps and in squalid neighborhoods in neighboring Jordan.

Hospitality fades

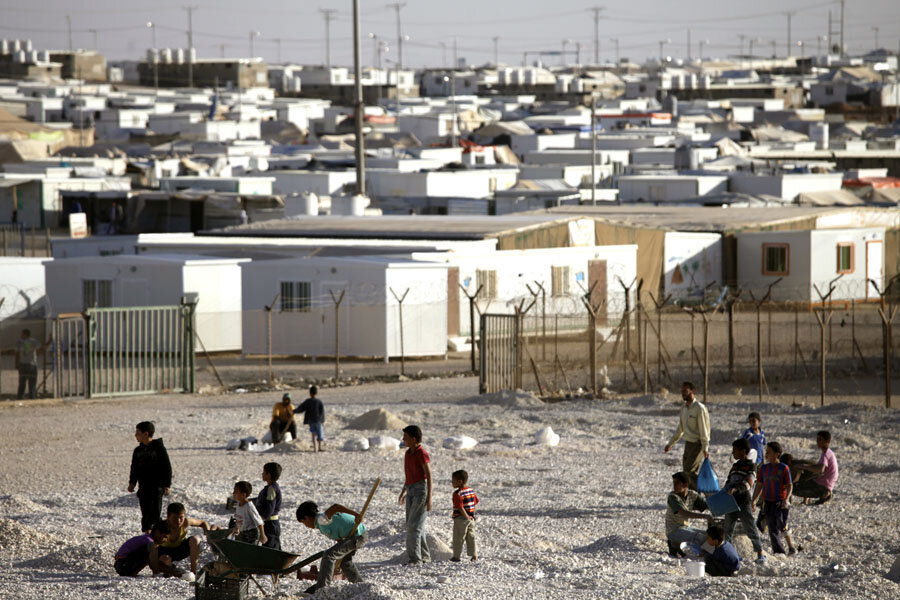

With a daily influx of Syrians, hospitality and resources in Jordan are starting to wear thin. Zaatari alone houses some 160,000 refugees, the world’s second-largest camp and now the fourth-largest city in Jordan, a country of 6.5 million. The total number of Syrians in Jordan is put at 500,000, with many of those living outside the camps and often working illegally.

UN-run refugee camps like Zaatari are largely unpoliced. Girls are terrified of venturing out to unlit bathrooms at night, says Bushra, a widow and mother of four from Homs, who lived at a northern refugee camp for four months.

“We heard all the time about kidnappings and rape of girls. I never let my daughters leave the tent,” she says.

Bushra, who like all of the Syrians interviewed for this story did not want her full name used, smuggled her family out of the camp and found lodgings in Amman. But this has not allayed her fears of violence against her two teenager daughters. Now she is considering finding husbands for them, which she says would be out of the question had they stayed in Syria.

While the minimum marriage age in Jordan is 18, a special waiver requiring official identification papers can be obtained for children as young as 15. For Syrians who arrive with little more than the clothes on their backs, informal marriages are often preferred.

The process includes a brokered dowry and an unauthorized sheikh. The contracts, which require women to forgo many of their legal rights, are illegal under Jordanian law.

Maha Homsi, a UNICEF child protection specialist in Jordan, says that in 2012, 18 percent of the registered marriages of Syrians in Jordan involved girls under the age of 18, up from 12 percent a year before. As most such marriages go unregistered, however, numbers are thought to be much higher.

But "what’s really alarming here is that 48 percent of the [informal marriages] Famil cases involve men 10 years or older,” says Ms. Homsi. That is above the age difference accepted in many Arab societies, she says.

Economic hardship is one factor driving Syrian women to marry early. Another is family honor. “The majority of Syrian refugee marriages are sutra [protection marriages], for the protection of her honor and womanhood,” says Ms. Homsi.

Fears of online trafficking

Women from the Arab Levantine, referring to Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan, are often characterized as the most beautiful in the Arab world. So the idea of rescuing a “Levantine houriya [virgin]” has fired the imaginations of wealthy Arab men. Requests for such women from countries like Saudi Arabia and Egypt abound in Internet forums, classified ads, and matchmaking networks.

“Honestly I am looking for a Syrian woman with the following qualifications: she must know the path of Allah and the meaning of raising a family; she must be very beautiful, with white skin and smooth hair,” one Facebook post read, purportedly by a married Egyptian university professor.

Moreover, Saudi clerics have issued fatwas encouraging marriages with Syrian widows and girls, deeming the act a form of Islamic charity. The men fulfill a Muslim deed by rescuing girls from exploitation and shame, while also supporting the admirable Syrian revolution, the fatwas state. Saudi Arabia, a Sunni state, has armed and financed rebel forces fighting President Bashir Al-Assad, who belongs to a sect of the rival Shiite community.

Yet the phenomenon has also incited outrage in Arabic language press and social media sites, which say the practice treats vulnerable women as war booty.

Hammoudeh Makkawie, the Amman coordinator of “Refugees, Not Prisoners,” a campaign group for female Syrian refugees, criticizes the hypocrisy of wealthy Arab men driven by ‘white knight’ fantasies.

“In Arab countries there’s support only for weapons, violence, terrorism, there’s no support for women,” he says.

The campaign organizes workshops for displaced Syrian women in countries like Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, in hopes of raising awareness of the dangers of “protection marriages.” The activists also offer vocational training programs to help women earn money so that they can stave off unwanted suitors.

Nour, a teenager who also escaped from Homs, wishes she could have joined such a training program. When she fled two years ago with her family to a camp in Jordan near the Syrian border, her mother refused dozens of marriage requests from Jordanian and Gulf men, saying it was a matter of dignity.

Now married to a Syrian and four months pregnant, she regrets having not finished her medical studies. She prays that her two “very smart” younger sisters can stay in school and not succumb to offers of an early marriage.

When relatives from Syria call, she tells them to stay there. “In our country it’s easier, even though there is war,” she says.