As ISIS advances, what future for Iraqi Christians?

Loading...

| Dair Mar Matti, Iraq

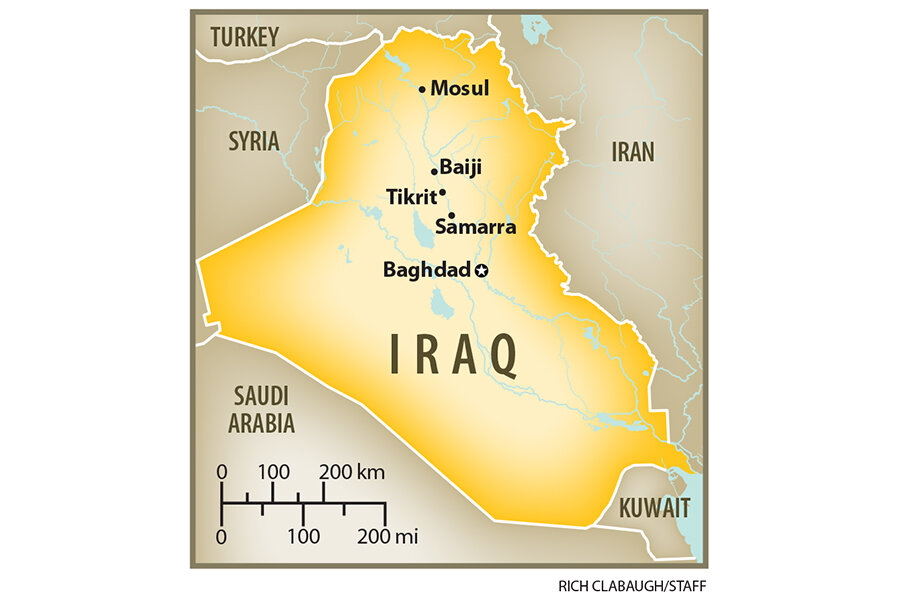

Just a few miles from Mosul, the map of Iraq is being redrawn in a cataclysmic restructuring of an area that was home to some of the earliest Christians.

The takeover of the city and wide swaths of other territory by the Al Qaeda offshoot Islamic State of Iraq and Syria has pushed half a million people out of Mosul, including tens of thousands of Christians and members of other ancient Iraqi religious minorities that have been a target of Al Qaeda attacks. Most of them are seeking refuge farther north in Kurdish-controlled territories.

“I believe we are seeing a rearrangement of the region,” says Patriarch of Antioch Ignatius Aphram II, the new head of the world’s Syriac Orthodox Christians, as he visits a 4th-century monastery. The monastery, like most other communities, has taken in dozens of families who have fled Mosul, one of Iraq's largest cities. Amid the stone walls, the faithful seeking blessings throng to kiss the jewel-encrusted gold crosses draped on the patriarch's purple robes.

“The last time the region was split into countries and states was during the Sykes-Pikot agreement,” he says, referring to the agreement a century ago between France and Britain that carved up the Middle East. “I believe we are seeing a new Sykes-Pikot in the works.”

Few communities here feel more vulnerable than the cities and towns along the Nineveh plains between Mosul and Kurdish-controlled Iraq – the heartland of Christian and other ancient minorities considered infidels by ISIS. Although part of the northern Iraqi province of Nineveh, they are within territory claimed by both the Kurdish region and the Iraqi central government.

Along with Iraqi Shiites, Christians and other minorities have been targeted by Sunni extremists for the past decade – much of it in waves of violence centered in Mosul and Baghdad. But the fall of Mosul marks the first time the entire city has fallen under their control.

“Most of our people in Mosul were too afraid to stay when the soldiers left the city along with police and all the security forces,” says Monsignor Amil Nouna, the Chaldean Catholic Bishop of Mosul, in the courtyard of a church in Bashiqa, less than 20 miles from his occupied home city. "Christian families, Muslim families, they all left and came to this region.”

Some of the roughly 80,000 Christians who fled – almost 90 percent of the Christian population of Mosul – are waiting to return home. Many others are trying to join relatives in the West. Since 2003, two-thirds of Iraq’s 1.5 million Christians have emigrated, a move church leaders believe is the death knell for Christianity in the Middle East.

“We have been here since the beginning of Christianity. We were here even before the beginning of Christianity,” says the patriarch, whose church was first founded in Antioch in present-day Turkey in 37 AD. “The blood of our martyrs is mixed with the soil here, some of the apostles of the lord Jesus were here and they preached the gospel in this land.… How can you tell people to leave here? How can you encourage them to leave this much behind?”

Bashiqa is dotted with churches, mosques, and the Yzedi temples, another ancient faith, in a testament to centuries of religious coexistence here. In the church courtyard as the monsignor spoke, veiled Muslim women from Mosul lit candles to the Virgin Mary – revered by both Muslims and Christians.

In Mosul, though, that tranquility came to an abrupt end as Al Qaeda put down roots after the US invasion of Iraq. Monsignor Nouna’s predecessor was kidnapped and killed there in 2008.

“I was there until 2006, when they shot my older brother, so me and my family had to leave Mosul because they tried to kill my youngest brother,” says another priest from Mosul, Father Youssef Ibrahim. “Since then we are living in the Nineveh plains.”

For now, according to Mosul residents who have gone back, ISIS is trying to make clear that citizens of all faiths will be protected in its version of an Islamic state. While new city bylaws distributed last week recommend that women dress modestly and remain in their homes, Christians have been told they will be protected along with other city residents.

The communities along the Nineveh plains and Kurdish authorities are taking no chances, however. Kurdish peshmerga fighters have moved farther south to fill the vacuum left by Iraqi security forces retreating in the face of the ISIS onslaught. The joint peshmerga-Iraqi Army checkpoints hailed as breakthrough by the US government in defusing Kurdish-Arab tensions just three years ago are now manned only by the Kurds.

At one village school, closed after the fall of Mosul, Kurdish fighters patrolled the roof and stood watch from classrooms emptied of desks.

In Karamlas, where residents six years ago dug a trench around the town in fear of Al Qaeda fighters, entrances to the town were sealed with parked cars. “How do I know you’re not ISIS?” asked an armed civilian, stopping strangers from entering the town before summoning the local priest.