Israel’s own ‘witch hunt’ ... and a test for the rule of law

Loading...

| TEL AVIV

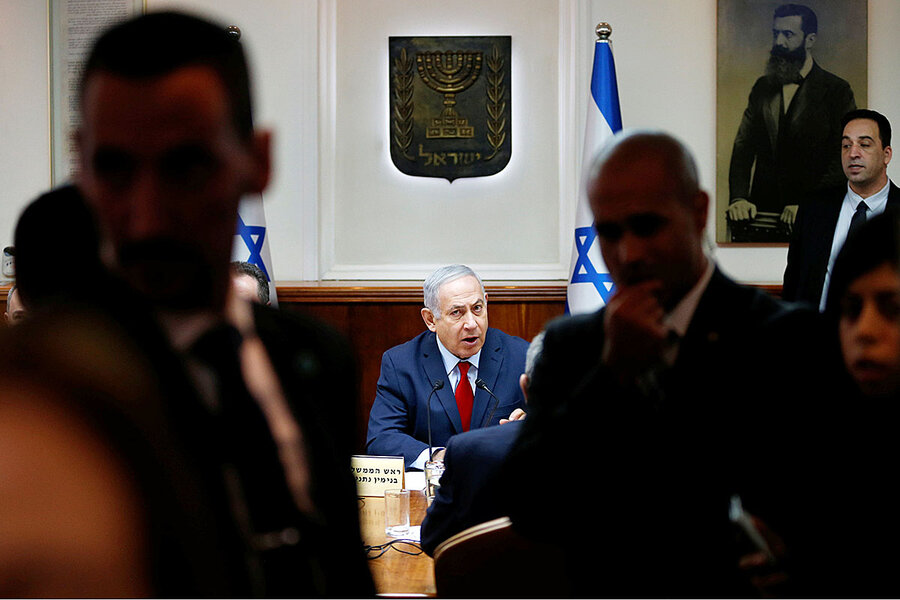

Israel has had corruption scandals. But now comes what is shaping up to be a real collision between political survival tactics and the rule of law. Police investigators say Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu should be indicted for dealings with an Israeli tycoon who owns the country’s phone monopoly and a news website. Mr. Netanyahu is alleged to have backed regulations that benefited the phone company in return for favorable news coverage. Netanyahu has shown no signs of stepping down, and is denigrating Israeli law enforcement and media, accusing them of conspiring to bring down a lawfully elected government. He has political cover. The decision to indict rests with the attorney general, a political appointee, and former Netanyahu aide. And there is no law that disqualifies an indicted prime minister from continuing to serve. Critics say Netanyahu is imperiling democratic institutions. “Everything is being undermined,” said law professor Yedidia Stern, vice president at the Israel Democracy Institute, in a radio interview. “There’s no reason to think that the rule of law in Israel is fortified in a way that it can’t be cracked. We are cracking it daily in our arguments.”

Why We Wrote This

Corruption allegations against Benjamin Netanyahu raise basic questions: To what extent may an elected leader maneuver to stay in power, and at what cost to democratic institutions?

Allegations by the combative head of government of a sustained “witch hunt” by prosecutors and the media. Talk of a looming constitutional crisis. Heard this all before?

The leader being scrutinized, however, is not President Trump, but Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who over the past two years has been the focus of a raft of bribery investigations.

Yet with legal pressures mounting, the deft political tactician shows no signs of stepping down, instead denouncing the police and setting up what some say is a collision between political survival tactics and the rule of law in a democracy.

Why We Wrote This

Corruption allegations against Benjamin Netanyahu raise basic questions: To what extent may an elected leader maneuver to stay in power, and at what cost to democratic institutions?

Israel certainly has had its share of political corruption scandals: Two prime ministers have even been forced to resign.

But now, after police investigators said last week that Mr. Netanyahu should face charges in a third bribery case – this time for dealings with an Israeli tycoon who owns the country’s fixed-line phone monopoly and a news website – Israel finds itself heading into uncharted legal and political waters ahead of an election scheduled for next year.

Netanyahu’s campaign to insist on his innocence and stay in office has many worried that his attacks on Israel’s legal institutions may do lasting damage.

Israeli voters might face the choice of reelecting a prime minister whom the police have recommended be indicted – or who already has been indicted. At the same time, Israel’s Supreme Court might find itself weighing an appeal to order the prime minister to resign, as it has done in the past with other elected officials under indictment – setting up a potential showdown between Israel’s executive and judiciary branches.

“We are already in the middle of constitutional crisis,’’ says Avraham Diskin, professor of political science at Hebrew University. “According to many prosecutors, Netanyahu should resign if he is indicted. That means just by indicting someone – without even convicting them – it’s possible to change the government in Israel.”

The corruption cases

Concluding its investigation into what has been dubbed “Case 4000,” the police said last week that Netanyahu pushed regulations favoring Israel’s telephone monopoly, Bezeq, to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars. As an alleged quid pro quo, the police said, the company’s controlling stakeholder, Israeli tycoon Shaul Elovitch, allowed Netanyahu and his wife, Sara – also implicated in the case – to dictate content decisions on the news website Walla, which Mr. Elovitch also owns.

Earlier this year, the police recommended Netanyahu be indicted in two other bribery cases. In “Case 1000,” the police allege that the prime minister accepted gifts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars from Israeli tycoons. And in “Case 2000,” Netanyahu is accused of offering to pass legislation that would improve the competitive position of the daily Yediot Ahronot newspaper against a rival, in return for favorable coverage.

(There is a “Case 3000.” Netanyahu is not a suspect in that investigation, but his brother-in-law, a lawyer, is. He was paid for advising a German submarine maker that sold hundreds of millions of dollars worth of Dolphin submarines to Israel.)

“The chance that Netanyahu will be indicted on criminal charges, at least on breach of trust, is significantly greater than the chance that these three cases will be closed without anything,” wrote Chen Maanit, a legal columnist for the Israeli financial newspaper Globes. “And a situation in which a prime minister is put on criminal trial while continuing in office is unacceptable.”

Anti-police sentiment

Echoing Mr. Trump, Netanyahu has inveighed against Israeli law enforcement, prosecutors, and the Israeli media – accusing them of conspiring to bring down a lawfully elected government.

“The witch hunt against me and my wife continues,” he said, accusing the police of deliberately targeting himself and right-wing politicians, while ignoring ties between newspaper publishers and opposition figures. Since the start of the police investigations against him more than two years ago, Netanyahu has repeated the mantra that “nothing will come of it, because there’s nothing” to the allegations.

Critics say Netanyahu is fanning conspiracy theories to inflame public sentiment against the country’s police, prosecution, and the courts – imperiling institutions at the heart of Israel’s democracy.

“You can’t sacrifice everything in order to delegitimize those who are investigating you,” said Yedidia Stern, a law professor at Bar-Ilan University and vice president at the Israel Democracy Institute, in an interview with Israel Radio.

“Everything is being undermined,” he said. “There’s no reason to think that the rule of law in Israel is fortified in a way that it can’t be cracked. We are cracking it daily in our arguments.”

Layers of political protections

Conspiracy theories and rhetoric aside, there are layers of political protections that Netanyahu can marshal.

The ultimate decision on whether or not to take the prime minister to court, and what the severity of the charges should be, belongs to Attorney General Avichai Mandelblitt, a political appointee of the prime minister who served as Netanyahu’s cabinet secretary.

Critics of Mr. Mandelblitt have accused him of slow-walking the decision on whether or not to indict, and warned he plans to water down the charges. A former justice minister said Mandelblitt should have recused himself from handling the case.

There is no Israeli law that disqualifies a prime minister who has been indicted from continuing to serve, but there is a judicial precedent: The Supreme Court has ordered government ministers and other officeholders to step down after being indicted. The court would likely be called on to decide if the same precedent should be applied to a prime minister, but this time it would likely mean bringing down the government.

Though parliamentary elections are scheduled for next November, Netanyahu could call a snap vote. His authority is unchallenged within his Likud party, which has continued to lead public opinion polls despite the corruption allegations. If reelected, the prime minister could use that vote as a populist flak jacket against political or legal pressures to resign the premiership.

“Bibi could run as someone under investigation, and if he wins he could claim that he has a popular mandate,” says Jonathan Rynhold, a political science professor at Bar-Ilan University. “The danger is that the Netanyahus will go right up to the edge of what is permissible. He’ll stir it up into a major political crisis.”

Two who resigned

Former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert was forced to resign in 2008 by his coalition partners when indictment over his involvement in a Jerusalem real estate project became unavoidable. He eventually was convicted and sent to jail. Ending his first tenure as prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin resigned on his own initiative in 1977 after it was revealed that his wife, Leah, had an illegal foreign currency bank account.

If Netanyahu were charged, his fate ultimately would lie in the hands of the right-wing and religious parliament members who are partners in his coalition. Meanwhile, the Likud has sought to pass laws that would shore up the power of the prime minister. Earlier this year, the coalition tried to pass a law to protect a sitting prime minister from indictment, but the measure did not advance.

Compared with the United States, where the president is limited by the constitutional checks and balances of Congress and the courts, an Israeli prime minister with a loyal majority has more power to stay in office at all costs short of a conviction.

“We don’t have a constitution ... and there are no term limits,” says Tal Schneider, a political correspondent for Globes. “The government controls the parliament, and the government can change the laws. Here, the opposition is only getting weaker.”