In Iran, outrage over patriarchy spurs change

Loading...

| LONDON

The tug of war over the role of women in Iranian society – a battle that has been going on since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 – has taken a new turn.

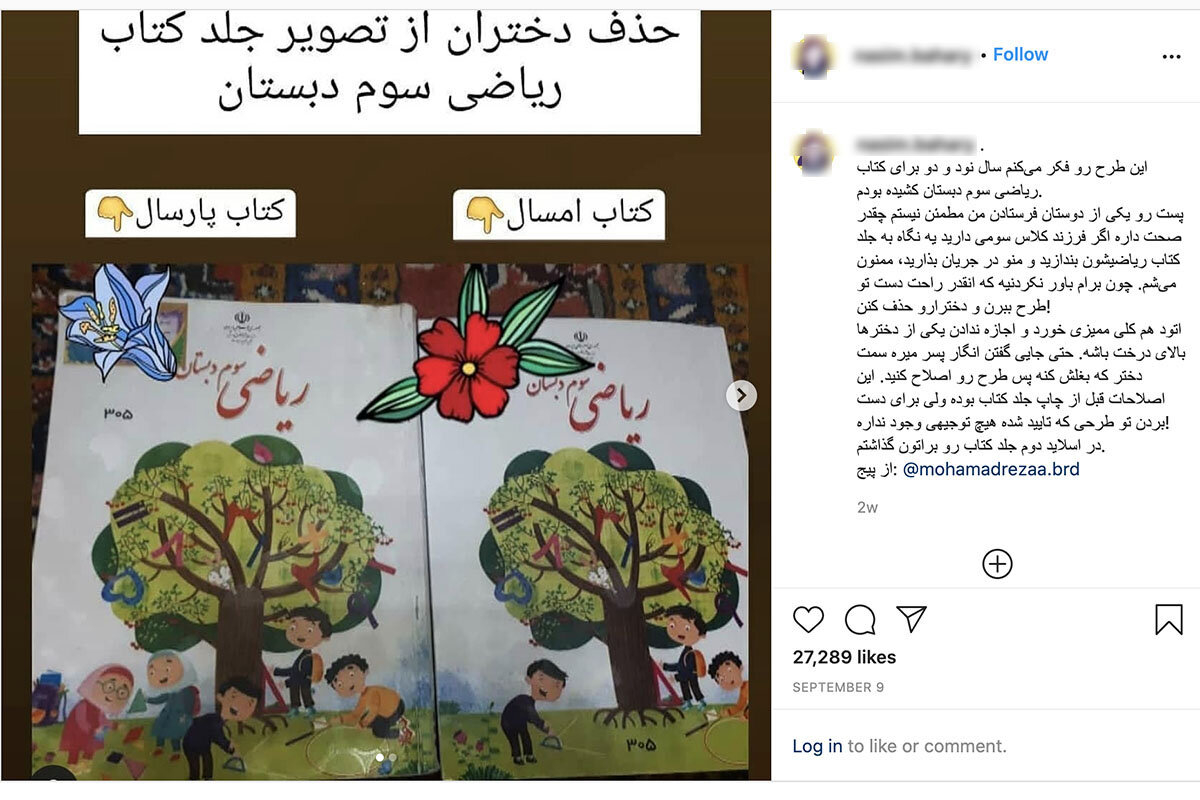

A recent court ruling, sentencing a man to just nine years in jail for the “honor killing” murder of his daughter, sparked unusual public outrage. (A woman was recently imprisoned for 15 years for removing her head covering in public.) Then parents ridiculed the Education Ministry for removing two girls from the cover of a third grade math textbook, leaving only boys in the illustration.

Why We Wrote This

How does change come to a traditional society? In Iran, a lenient sentence for the murder of a 14-year-old girl and the removal of girls’ images from a math textbook are fueling anger at the patriarchy.

Such was the level of anger at the girl’s murder that parliament finally passed a law against child abuse that had been stalled for 11 years, and it is moving on a bill to criminalize violence against women.

“There is an emerging and fast-growing trend among different layers of the Iranian public to demand answers and accountability,” says a sociology teacher in Tehran.

First there was popular outrage in Iran over the sentence handed down to a farmer who killed his own 14-year-old daughter, Romina, in a so-called honor killing.

Last month the father was sentenced to just nine years imprisonment for the murder, despite calls from even hidebound Iranian conservatives for “severe” punishment.

Then popular anger was stoked again when third grade math books were handed out in classrooms this month. The cover image had been modified – removing two girls but leaving three boys – because from an “aesthetic and psychological point of view,” the Ministry of Education said in a statement, the scene was “overcrowded.”

Why We Wrote This

How does change come to a traditional society? In Iran, a lenient sentence for the murder of a 14-year-old girl and the removal of girls’ images from a math textbook are fueling anger at the patriarchy.

The two episodes have shone fresh light on systematic gender discrimination in Iran, and the popular outcry has forced change on the ruling elite.

They are the latest incidents in the constant tug of war over the role of women in Iranian society. Ever since the 1979 revolution, it has pitted a traditional patriarchal Islamic system bent on imposing control and restrictions on women – such as one-sided divorce laws and the mandatory wearing of a hijab head covering – against increasingly powerful demands by women for equal rights and recognition.

Demand for accountability

“There is an emerging and fast-growing trend among different layers of the Iranian public to demand answers and accountability,” says an Iranian sociologist, a lecturer at a university in Tehran who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the issues.

The lenient court ruling in Romina’s case was widely denounced as a case study in women’s inequality and the diminished value of girls. By contrast, a woman was recently sentenced to 15 years in prison for removing her headscarf in public.

“Romina’s father picked up the sickle in full consciousness and beheaded his teenage daughter, because he was aware of the anti-women laws of this country,” fumed female journalist Niloufar Hamedi on Twitter. The father had checked with a lawyer before the murder, to be sure he would avoid the death penalty.

In the case of the math textbook, parents saw a government ploy to literally render girls invisible. They forced the education minister to apologize and launched a campaign to put new covers on the books that often include an image of the late Iranian mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, who in 2014 became the only woman ever to win the prestigious Fields Medal, the math equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

“The wrath against the [honor killing] verdict has not been exclusive to elites, intellectuals, and women’s rights activists,” says the university sociology lecturer. “It’s been more far-reaching and has been expressed even by conservative-minded people.”

Popular anger over the gruesome murder in May of Romina, a schoolgirl who ran away from home with her older boyfriend, led the Iranian parliament to approve measures criminalizing child abuse and neglect, now called “Romina’s law,” that had been stalled for 11 years.

Another law that would criminalize sexual and physical abuse of women, first written 10 years ago, is also moving forward, albeit slowly.

Parents get book recovered

The textbook cover change has prompted many parents to seek to hide the offending image. When the father of a third grader visited a stationery shop in Tehran recently, the owner offered him three different images of Ms. Mirzakhani – the math medal winner who taught at Stanford University.

“I have had eight customers today with different photos of Maryam, asking me to print them on the cover. Who are these sick people [officials behind the removal]?” he wondered. “They can’t even tolerate pictures of two little girls in hijab?”

In mid-September, the uproar prompted the minister of education, Mohsen Haji Mirzaee, to issue a formal apology, saying there was “tastelessness behind such a decision.”

He also praised Iran’s support for female education: “The old-time discrimination that characterized women’s access to education has been entirely abolished,” he said. “Today, no girl is deprived of education in any spot in this country.”

Achievement and hurdles

Indeed, Iran is renowned for the most widely and highly educated female population in the region. Women fill 60% of the country’s university places. Despite challenges, Iranian women from Iran have been ministers, lawmakers, professors, lawyers, firefighters, and even an astronaut and Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

But the controversy has exposed again how Iranian textbooks are slanted toward masculine names and images, with one former official recently putting the figure at 70% in favor of boys.

Research into the “role and status of women” in Persian textbooks by the state-funded Center for Cultural Studies and Research in Humanities found in 2007 that only 16% of 3,029 names used were female, only 37 women were among the 782 prominent figures mentioned in lessons, and only one woman was listed among 122 notable personalities.

Agreeing that the cover “should not have been changed,” the deputy minister of education whose bureau is responsible for the math book, Hassan Maleki, demands that critics “should be fair.”

“Why don’t they see the cover on the science book for the same grade?” he asks. “The kids on that book are all girls. This indicates that there is no negative approach toward girls,” he argues.

The covers of most school textbooks in Iran show either boys or girls, but not both. This seeks “to institutionalize gender segregation among children and to indirectly teach them the very concept from such very early stages,” worries the Tehran sociologist.

For her part, the cover designer, Nasim Bahary, says she was surprised by the Education Ministry’s move, because she thought she had already complied with “multiple censorship orders” imposed in 2013 that led to the previous cover design showing both girls and boys.

But it was no surprise to Ebrahim Asgharzadeh, one of the student leaders of the 1979 U.S. Embassy seizure in Tehran, who today is a reformist politician.

“The policy of elimination [of women] and gender segregation has hit rock bottom,” he said in an Instagram post. He urged his daughter to “paste the photo of Mirzakhani on the cover of the book and take pride in being a girl.”

An Iranian researcher contributed to this report.