At oldest Palestinian camp in Lebanon, violence adds to struggles

Loading...

| SIDON, Lebanon

Ain al-Hilweh, the oldest and largest Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, was created in 1948, when Palestinians uprooted by the war that accompanied the formation of the state of Israel fled north.

In recent weeks, the camp has been the site of an eruption of deadly clashes between Palestinian factions and Islamist militants, drawing the attention of the Lebanese army and raising the prospect of an even more destructive battle.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAn eruption of violence has brought into sharp focus the oft-forgotten plight of Lebanon’s Palestinians, who for decades have lived in crowded camps amid chronic poverty and limited services. Yet individuals strive to maintain dignity and hope.

For Mahmoud, who was born at the camp and has taught there for 30 years, the lethal escalation signifies a deeper crisis for Palestinians in Lebanon, a further affront to their dignity after decades of dislocation and poverty.

“We face a problem today as Palestinian people: The world takes a different view of us, after they see what happened in Ain al-Hilweh,” says Mahmoud. “We are proud people; we are well known for how well educated we are,” he adds. “What we are demanding now is to control these weapons all over the place.”

Mahmoud says “shrinking” opportunities and poor education have led young men to find paid work with armed groups, but he teaches his students to “see their future differently.”

“Our duty is to treat the problem, to make changes,” he adds. “It’s hard, but it’s not impossible.”

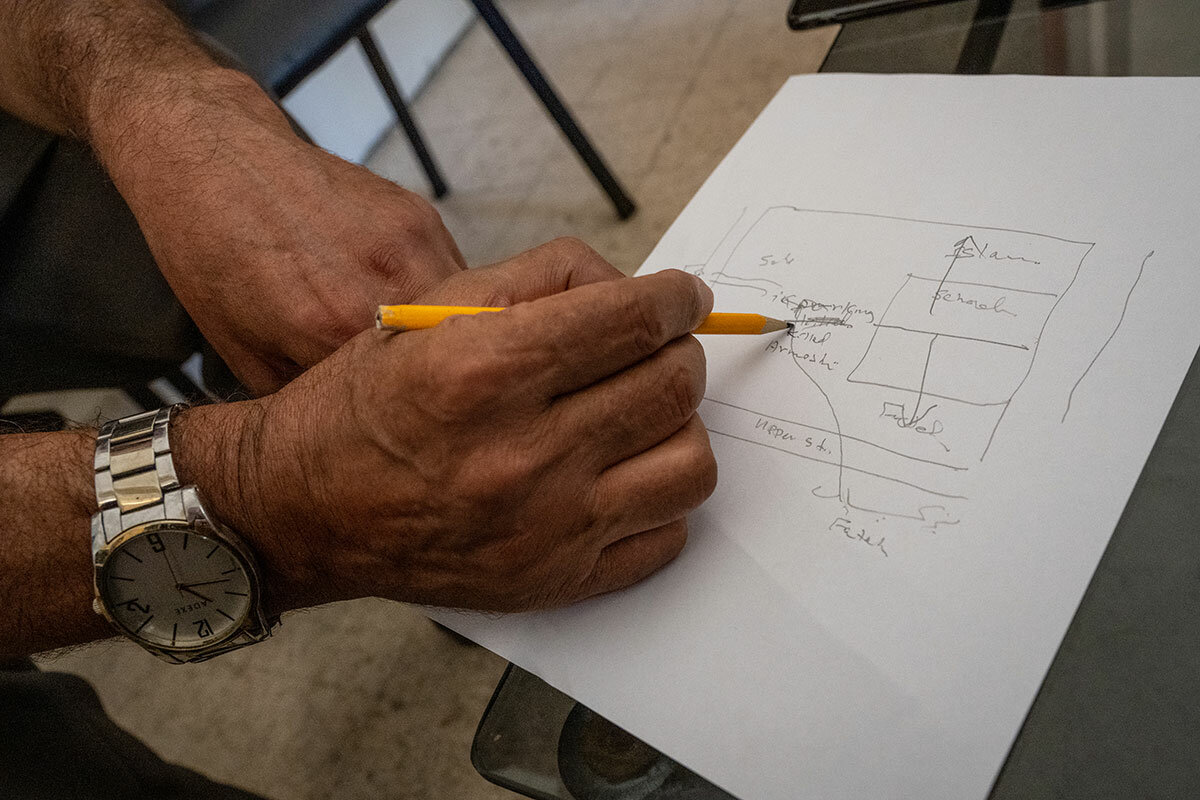

With a yellow pencil missing its eraser, the Palestinian educator draws from memory the layout of fortress-like schools in the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp in Lebanon that have become the front line in a fight between Palestinian factions and Islamist militants.

Teacher Mahmoud, who asks that his full name not be used, knows every inch of Lebanon’s oldest and largest camp for Palestinian refugees: He was born there, taught for 30 years there, and feels deeply how surges of violence raise the level of anguish inside the overcrowded camp.

He points to a school parking lot on his map. Here, says Mahmoud, is where a senior commander of the mainstream Palestinian Fatah faction, Abu Ashraf al-Armoushi, and four of his bodyguards were ambushed and killed by Islamist militants at the end of July. The attack deepened a blood feud and led to days of clashes that left 13 people dead and forced 4,000 from their homes.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAn eruption of violence has brought into sharp focus the oft-forgotten plight of Lebanon’s Palestinians, who for decades have lived in crowded camps amid chronic poverty and limited services. Yet individuals strive to maintain dignity and hope.

Violence erupted again over this past weekend, wrecking a fragile four-week cease-fire with heavy gunfire and explosions that spread across much more of the camp. Another cease-fire agreed to Monday collapsed by Wednesday night, reportedly bringing the death toll of the newest fighting to 16.

Lebanese Army Forces began to deploy toward the camp, raising the prospect of a broader and more destructive battle. A hospital was evacuated after its walls were struck by bullets, and – with several schools occupied by fighters and damaged in the fighting – the United Nations is urgently looking for safer alternatives for 5,900 students to start the school year.

For Mahmoud, the lethal escalation signifies a deeper crisis for Palestinians in Lebanon, a further affront to their dignity after decades of dislocation and poverty.

“The Palestinians here want to go back, but they can’t go back home, and 75 years in we have an unresolved economic, social, and status issue, and it translates into these situations as we see in Ain al-Hilweh,” says Dorothée Klaus, Lebanon director of the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, or UNRWA.

“We are proud people”

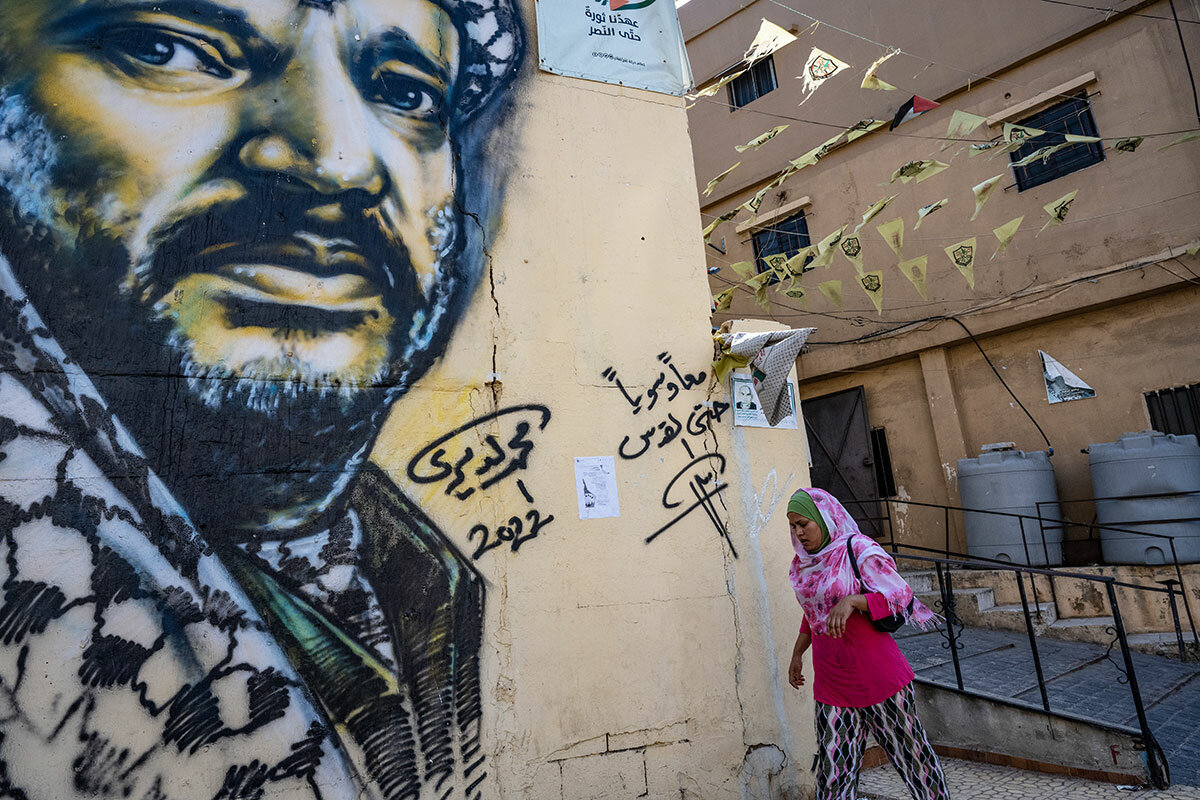

Ain al-Hilweh was created in 1948, when Palestinians uprooted by the war that accompanied the formation of the state of Israel fled north. More recently, residents of the camp include Syrian refugees and remnants of the Islamic State and Al Qaeda, as well as known fugitives.

“We face a problem today as Palestinian people: The world takes a different view of us, after they see what happened in Ain al-Hilweh,” says Mahmoud, speaking after the first round of clashes. He now lives outside the camp but provides services inside such as music, gym, and school support, which he says teach students to “see their future differently.”

“We are proud people; we are well known for how well educated we are,” he says. “Now the whole world is looking at us as a bunch of ignorant people in the camps, and this is something we are suffering from.”

The escalating violence has brought into sharp focus the oft-forgotten plight of some 200,000 to 250,000 Palestinians in Lebanon, who for decades have lived out of a dozen crowded camps where unemployment and poverty are chronic, services are limited and shriveling, and paroxysms of violence by a multitude of factions vying for control are frequent and destructive.

The result has been widespread atrophy in this society of refugees. They say they are struggling to hold on to their history, and to pass from one generation to the next a hopeful ambition of “going home” to a Palestine that no longer exists as they remember it.

During the clashes Sunday night, rocket fire from inside the camp also struck two Lebanese Army Forces bases, prompting the army to warn of “consequences.”

Those warnings raised concerns among residents of a repeat of the events of 2007, when the army destroyed the Nahr al-Bared camp during a 15-week campaign to rid it of Islamist groups. Lebanese authorities have no jurisdiction inside the Palestinian camps; under a decades-old agreement, a committee of Palestinian factions rules the camps.

The International Committee of the Red Cross “is extremely concerned by the alarming intensification of armed violence seen in Ain al-Hilweh camp, as the constant violence over the last days had a profound impact on people’s lives, homes, essential services, and infrastructure,” says Shady Ramadan, head of the south Lebanon subdelegation for the International Committee of the Red Cross.

“We are continuing to provide critical assistance,” he says, including supplying the hospital and treating wounded people.

For teacher Mahmoud, the fresh violence has multiple threads.

“What we are demanding now is to control these weapons all over the place,” says Mahmoud, who describes how “shrinking” opportunities and poor education have led young men to find paid work with armed groups as a job only, instead of for “ideological reasons, for Palestine.”

“These [Islamist] people in the camp, they belong to a master; they are tools in the hands of someone,” says Mahmoud. “Some people take orders from others without thinking. Some people underestimate the impact of clashes, and what it means to grab a gun and open fire inside the camp ... which shuts everything down.

“Our duty is to treat the problem, to make changes,” he adds. “It’s hard, but it’s not impossible.”

Resources in chronic short supply

Critical to making those changes is UNRWA, which has been charged since 1949 with the mammoth task of providing for all aspects of life for displaced Palestinians across the region, now an estimated 5.9 million refugees and their descendants.

At the end of August, UNRWA mounted an emergency appeal for $15.5 million to relieve the needs of those affected by the first round of clashes. The appeal noted that Ain al-Hilweh has become “a magnifier of different actors vying for control,” with humanitarian needs “high and rising, driven largely by systematic discrimination over generations, failed governance structures [and] unprecedented” economic crises.

Since taking her UNRWA post last February, Dr. Klaus meets every four weeks with all Palestinian faction leaders, including Islamic groups, to find better living solutions for refugees.

“What you have in Lebanon is a population that for 75 years has experienced recurrent hostilities, frequent displacement, and destruction through generations,” says Dr. Klaus. She ticks them off to include, after 1948, the destruction of three Palestinian camps in 1976 and the massacre in the Sabra and Shatila camp in 1982.

“This results in recurrent trauma, with no space for healing, and it translates often into severe depression [so] that people can no longer take care of themselves,” says Dr. Klaus.

Limited resources have been a constant problem since UNRWA began, with Dr. Klaus noting that reports sent to U.N. headquarters since 1949 have included requests for more funding.

The recent violence only compounds such problems, she says, with an estimated 30,000 textbooks stored in the occupied schools for the new school year likely destroyed, and reports of serious damage to buildings.

Opportunity for change

Still, as UNRWA searches for temporary solutions for students, Dr. Klaus says there may be a broader opportunity to build new school buildings that do not as easily lend themselves to becoming fortified positions for fighters.

“This is not a matter of reconstructing a school,” says Dr. Klaus. “This is reconstruction through a participatory, reflective process, involving the stakeholders about what society you want your children to grow up in.”

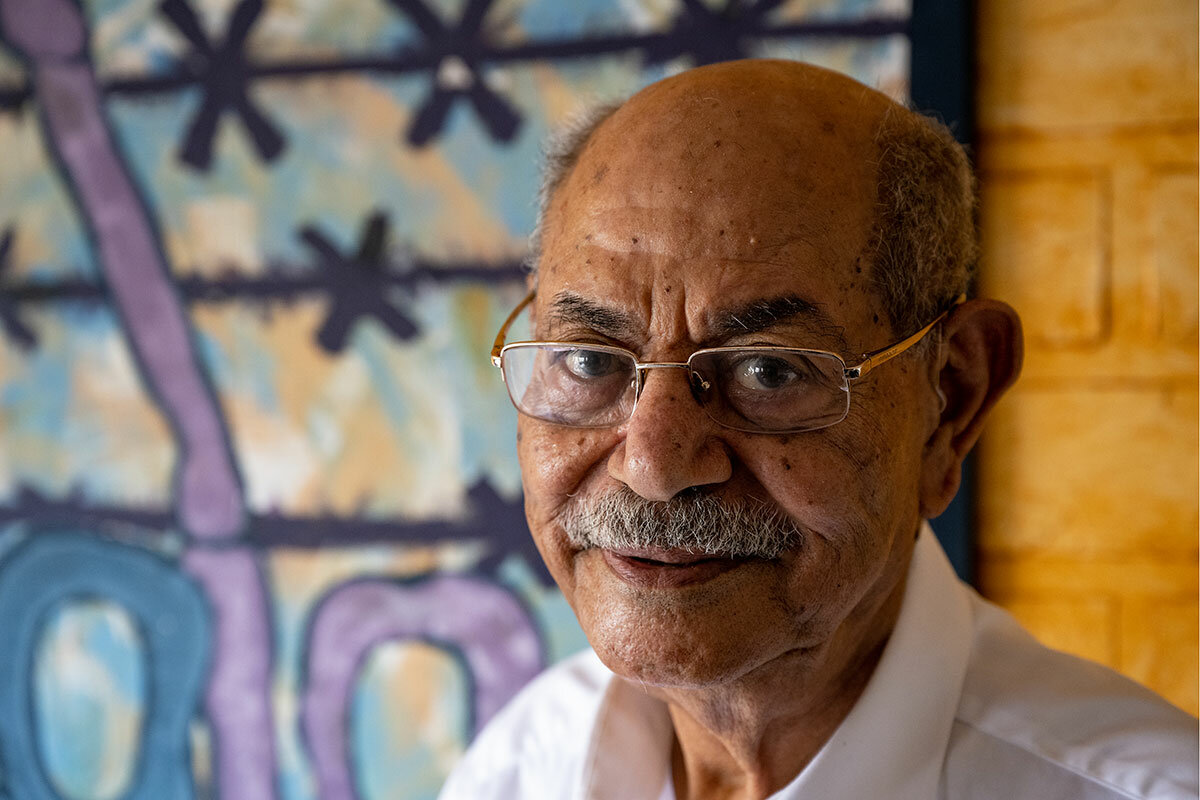

Such change is also the desire of Salah Salah, the octogenarian head of the refugees camps for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine in Beirut. He speaks of a young generation – including his son, Mohammed, a university student who sits beside him – doing better at easing the despair of Palestinian refugees.

He says the presence of Islamists in Ain al-Hilweh is “the same time bomb” that “could explode at any moment” that led to the destruction of the Nahr al-Bared camp in 2007. “We are dealing with confusion in the camps. ... You have to ask the Lebanese army how [Islamist militants] got there, and with those weapons.”

Mr. Salah asserts that there is a deliberate policy by Lebanon to keep Palestinians frustrated by barring them from certain professions and from owning property, and by the international community to pressure UNRWA to shrink services in camps, so that the Palestinians “will melt away.”

“People are frustrated, people are depressed, but we have a new generation in the camps that are educated to say, ‘No, no, no, we are Palestinians and we will defend our country and our rights,’” adds Mr. Salah. “They are rebelling against what is happening to them right now.”

“Look at my generation: What kept us going? We still talk about liberation, and we pass this hope to the next generation by teaching them who they are, and their place,” says Mr. Salah. “All talk is ‘Palestine, Palestine.’ ... Always ‘Palestine’ is in their mouth.”