Report: China bolsters state hacking powers

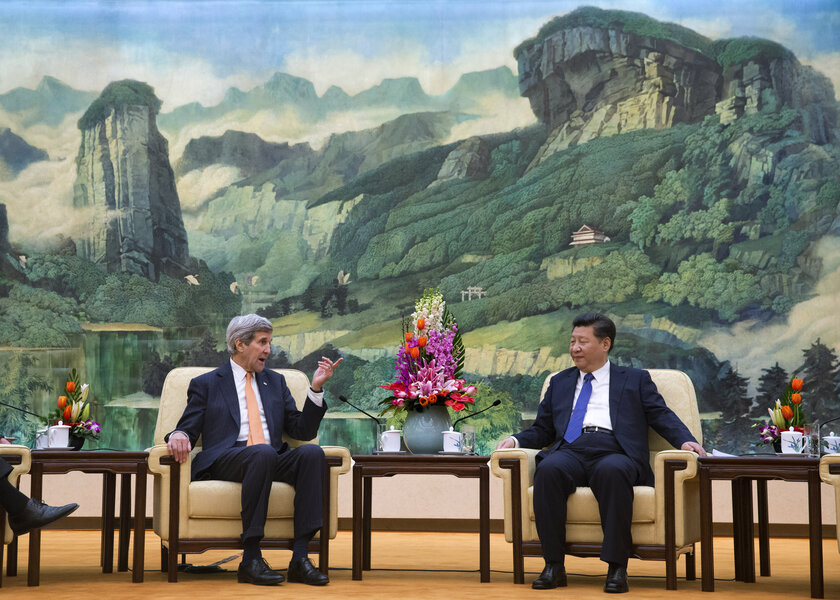

After the US and China inked a landmark agreement not to conduct cyberespionage to steal each other’s trade secrets, American officials wondered if Chinese President Xi Jinping would – or would be able to – keep up his end of the bargain.

US officials have long accused hackers from the powerful Chinese military of carrying out attacks on the US government and private companies, and September’s deal, to many experts, appeared overly optimistic.

As all eyes remain on President Xi, a new report by American cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike finds new evidence the leader is giving more power over the country's digital operations to the state-run Ministry of State Security (MSS) and the Ministry of Public Security (MPS). "We’re seeing a mission shift," said Adam Meyers, CrowdStrike’s vice president of intelligence.

The report released Wednesday says the move could be part of a broader effort to put more control over the country’s Internet operations under Xi – and a sign that he is trying to put China's military on a tighter leash.

However, the report found, the shift does not mean China's economic espionage is stopping – but it could mean Xi may have closer oversight over some of the organizations directing it. "Beneath the surface, however, China has not appeared to change its intentions where cyber is concerned," the report said.

In the first three weeks after the US and China agreed to halt economic espionage, CrowdStrike in October detected several Chinese attempts to steal intellectual property and trade secrets from American companies in the technology and pharmaceutical sectors – including those by Deep Panda, a hacking group that has been linked with the military.

CrowdStrike has now spotted more evidence that the civilian spy and homeland security agencies, Mr. Meyers said, have targeted foreign healthcare and technology firms to benefit the country's economic sector. The CrowdStrike report suggests Chinese hackers are likely to continue targeting industries such as agriculture, healthcare, and alternative energy – where China’s growth has lagged.

"Although the majority of MPS' actions aim to counter internal issues and enforce censorship for Chinese citizens, the global activities carried out by the MPS not only demonstrate the Ministry's capability and willingness to support [Communist Party] regulations and objectives, but also its intent to carry out operations on foreign soil," the report added. The agency is also, the report found, developing units within the People’s Public Security University in Beijing – China’s school for elite police training – to train hackers and carry out cyberattacks.

MPS, China’s chief homeland security agency, has indeed begun to play a leading role in enforcing new Internet restrictions and digital antiterrorism campaigns – including by arresting alleged online criminals, the CrowdStrike report said.

Some of those efforts began last August, when MPS announced the arrests of 15,000 people on charges they had "jeopardized Internet security" – part of a broader campaign described by the Chinese government as a plan to clear the Internet of illegal and harmful material.

CrowdStrike also traced massive denial-of-service attacks aimed at the coding website GitHub in April, which had hosted Chinese anticensorship websites, back to China’s Internet backbone, suggesting that high-level government officials may have known of the hack. Now, MPS will step up efforts to assert more control over online messages and content – including by running network security offices at Chinese Internet companies such as Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent.

The consolidation of power to civilian agencies is especially striking since it comes at a time when the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) plans to lay off 300,000 troops – the largest cuts for the service in almost a decade – and the military revamps under a unified command structure.

For years, US officials and experts have accused PLA hackers, especially Unit 61398, one of the army's top hacking units, of carrying out attacks on US government and private networks – potentially without coordination from the government. Though China has denied carrying out such espionage campaigns in the past, in 2014, the Department of Justice indicted five members of the PLA on charges of hacking into six US companies in the nuclear power, metals and solar products industries, as well as a labor organization, to steal intellectual property to benefit Chinese companies.

Xi has taken some public steps, however, that appear designed to demonstrate goodwill, especially as China was named the lead suspect in the massive Office of Personnel Management breach that compromised the personal information of nearly 22 million former and current US government employees. Beijing reportedly arrested several hackers in connection with the OPM hack, although public evidence substantiating those arrested were actually the true hackers has not been released.

Yet while Xi might have more leverage to stop hackers with the antiespionage agreement and the reorganization CrowdStrike describes, experts caution that cracking down on Chinese spying on foreign companies may that may not be his main priority.

"I think [Xi]'s serious about the commitment he made to President Obama, and there is a strong private hacker market in China that the Chinese try to control," said James Lewis, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. However, Mr. Lewis said, "priority No. 1 for them is political stability. If you're a hacker and you're committing crime, they may not like it, but you're not priority number one for them."

And now that he's taken steps to bring the country’s cyberoperations under his control, Xi may face a difficult balancing act when it comes to his priorities, experts say.

"[China is] worried about Chinese hackers threats to their own companies and to their own data, and then they have to balance that with the external pressures from the United States," said Adam Segal, a senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. "A lot of it is not completely under their control – since the hackers are freelancing and probably moving back and forth between the MSS and the MPS and commercial criminal networks. So, for whatever vision they have, at the end, it’s going to take them a while to get there."