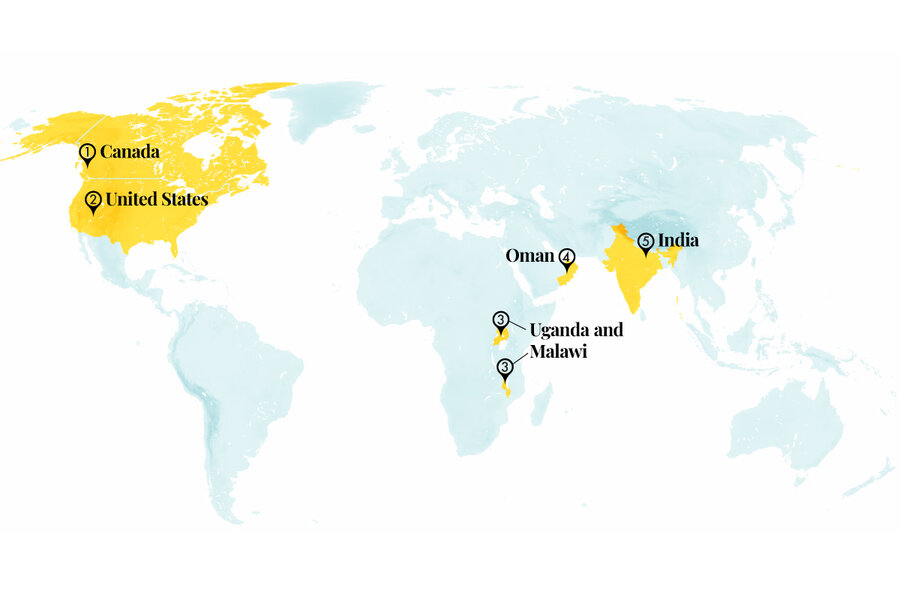

For safer drinking water, the ingenuity of simple solutions

1. Canada

Scientists used sawdust and tannins to trap microplastics in water, potentially paving a way to fight plastics pollution. A filter developed by a team at the University of British Columbia and in Chengdu, China, combined wood dust with the natural compound found in unripe fruit, creating a biodegradable material that trapped up to 99.9% of micro and nanoplastics.

Plastic debris from industrial waste and the breakdown of consumer goods can wreak havoc on aquatic ecosystems, in part by introducing toxic chemicals to marine life. For humans, the ubiquity of microplastics emerged with the first reports of plastics in drinking water in 2017. Researchers say their “bioCap”-filtered water, given to lab mice, demonstrated the effectiveness of the filter by showing a lower level of absorbed nanoplastics in the mice.

Scientists have struggled to find an effective method of filtering microplastics, which vary widely in size, shape, and electrical charge. But the team says that bioCap, made from renewable materials, can be easily scaled for both home and municipal use.

Sources: Advanced Materials, University of British Columbia

2. United States

To address the child care shortage, programs in Nevada and Colorado are helping to house child care providers. In many states, licensed providers who want to work in their own homes must own or rent a single-family home. High costs and objections to these home-based businesses by landlords and homeowner associations can be barriers to entry in an already low-wage industry. But new housing programs are boosting the Black and Latina women who are disproportionately represented in this workforce.

CARE Nevada, a partnership using state and private funds, acquires property and rents to caregivers who are vetted by the initiative. Mission Driven Finance – a social impact firm, which prioritizes public value in its for-profit investments – selects the homes and renovates them to child care standards. Renters pay a discounted rate and later have the option to buy. CARE Nevada hopes to double the number of in-home child care slots in Las Vegas’ Clark County by the end of 2024.

In southwest Colorado, nonprofit housing developer Rural Homes is using donated land and modular construction to funnel more homes to child care providers. In Ouray, a bedroom community near the wealthier Telluride, a survey by the nonprofit Bright Futures found that 80% of respondents don’t have adequate child care. Bright Futures identifies the caregivers who qualify for the homes. The program currently provides just two homes for child care, but it’s a substantial increase for Ouray’s 900 residents.

Sources: EdSurge, Urban Institute

3. Malawi and Uganda

The number of people with access to safe water in Malawi and Uganda doubled in the last 18 months. A nonprofit focused on scalable solutions, Evidence Action, provides free chlorine treatment via 52,000 dispensers that are serving 9.8 million people across both countries. Residents collect water at their community’s source and add pre-measured chlorine to reduce pathogens.

The United Nations estimates 33 children a day in Uganda and 1.2 million people worldwide each year die from diarrhea. Poor sanitation and hygiene cost Malawi $57 million annually in health care expenses and productivity loss.

Evidence Action says that its model takes inspiration from behavioral economics and that its intervention has achieved an adoption rate five times higher than other purification methods. The group’s chlorine dispensers now provide safe water for 10% of Uganda’s population and 15% of Malawi’s, and serve 2 million people in Kenya. The nonprofit hopes to expand its dispenser network and is evaluating an in-line chlorination system, which would add chlorine in pipes through a simple device installed near the water collection point.

Sources: Future Crunch, Evidence Action

4. Oman

Oman decreed a sweeping labor law that follows other reforms this year to improve conditions for private sector workers. The new law lowers the maximum workweek from 45 hours to 40, more than doubles the number of annual sick days, and increases the length of maternity leave from 50 days to 98 days – the highest in the region. The law also provides one week of paternity leave for the first time. Passport confiscation – commonly used to coerce migrants into forced labor – became illegal.

Worker advocates say the law is discordant with International Labor Organization standards on workplace discrimination, excludes domestic workers, and, unlike other Gulf countries’ laws, does not explicitly prohibit sexual harassment. Labor laws in Oman remain underenforced, particularly for migrants, who make up 80% of the country’s private-sector labor force. But some new protections were introduced. End-of-service benefits were increased, and a migrant worker who sues an employer for back wages is allowed to remain in the country until the case is decided.

Sources: Future Crunch, Migrant Rights

5. India

Kashmir banned corporal punishment in schools in response to the advocacy of mental health professionals and their reports of children requiring care after being punished at school.

In June, the Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences-Kashmir cited 106 cases from 2020 to 2022 in which children sought psychiatric care at the institute after experiencing corporal punishment. The institute’s letter to the Directorate of School Education Kashmir emphasized that corporal punishment has “severe, long lasting and detrimental effects on children’s mental and emotional wellbeing.” Across the country, media reports of corporal punishment also cite instances of severe physical injury and at least one fatality in December.

Although Kashmir was not subject to certain Indian laws when the country prohibited corporal punishment in 2009, the new ban references India’s provisions for imprisonment and fines for perpetrators of corporal punishment in schools. The directorate recommended promotion of healthy relationships and positive guidance rather than punitive action. An extensive list of physical and mental harassments, including intimidation and name-calling, are all banned. Among its other recent orders, the directorate made a no-homework rule for the youngest children and put weight limits on school bags.

Sources: Directorate of School Education Kashmir, Greater Kashmir, Hindustan Times