Land-mine casualties show signs of global decline

Loading...

In January 1997, Diana, princess of Wales, famously walked through an active minefield in Angola to raise awareness of the ongoing threats posed by land mines. During her visit, with the help of a removal expert, Diana detonated one of the remaining mines.

“One down, 17 million to go,” she said while pushing the button.

This year marked the 20th anniversary of the death of Diana, a passionate advocate for land-mine eradication, as well as the 20th anniversary of the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty. The treaty, signed Sept. 18, 1997, is an international agreement signed by 163 countries (most recently the Marshall Islands) with the goal of creating a mine-free world by 2025.

The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) and the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC) are sister organizations that monitor that 1997 treaty and the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, respectively. And each year, the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, a program within ICBL-CMC, issues reports on international progress.

The Monitor’s most recent reports did highlight some negative trends: 2015 reached a 10-year high with 6,461 mine casualties, and casualties from cluster munitions doubled in 2016 from the year before, to 971 casualties.

All land-mine casualties are unfortunate, says Stephen Goose, director of the Human Rights Watch’s Arms Division, but it is important to remember how far the world has come. Before the treaty in the mid-1990s, says Mr. Goose, it was common to have 26,000 casualties per year, almost nine times greater than recent annual rates. And despite the overall increase, largely due to the civil war in Syria, the majority of countries saw a decline.

“The increased casualties are alarming,” says Jeff Abramson, program manager at the Monitor, “but the bigger picture is that these have been successful treaties.”

International support for the treaties has not only drastically reduced civilian casualties, but also stigmatized the use of these weapons. Because of these treaties, even countries who are not signatories (such as the United States), feel a responsibility to disavow the new use of land mines and cluster munitions and aid cleanup efforts around the world.

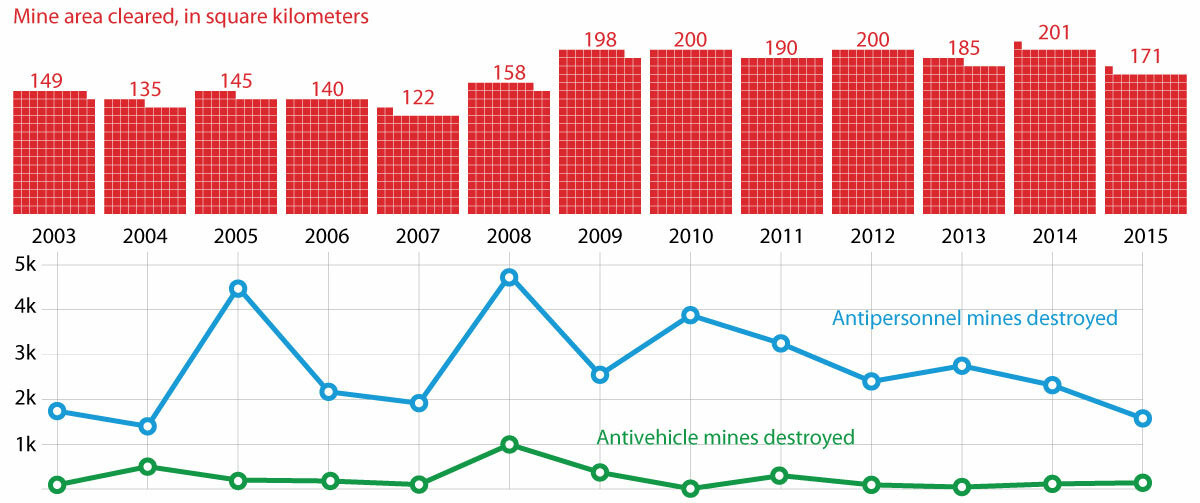

Cleared land, where children can walk to school without fear of stepping on land mines, is a direct result of this aid. According to the 2016 Landmine Monitor report, almost 370 square miles of land were cleared of mines in the past five years, destroying 1.3 million antipersonnel and 66,000 antivehicle mines in the process.

“Any time land mines or cluster munitions are removed from the ground there is tangible progress for the people who live in these communities,” says Mr. Abramson. “Every year you see land cleared, it means areas are available for people to farm or engage in livelihood.”

More than 77 percent of cleared land in 2015 occurred in Cambodia, Croatia, and Afghanistan, three countries where agriculture is a major part of the economy. In Afghanistan, for example, where almost 79 percent of the country’s labor force is employed by agriculture, 14 square miles were cleared in 2015 – enough land for 2,706 Afghans to start their own family farms.

“The human cost was huge, but there was also socio-economic cost,” says Goose at HRW. “Countries like Angola and Mozambique couldn't recover from war and build up their economy. They couldn't even drive on roads or get water. It was a concrete denial for a country to emerge successfully from war – all due to land mines.”

Along with land clearance, stockpile destruction is another preemptive protection effort that has seen particular success. Of the 163 states signed to the treaty, 156 have declared themselves stockpile-free – destroying more than 51 million undetonated antipersonnel mines in the process.

But above all, says Goose, the Mine Ban Treaty showed the world that diplomatic solutions can solve humanitarian crises.

“If the Mine Ban Treaty has made a difference in the world, it is because the partnership between governments and civil society forged through the process … has continued to this day,” Archbishop Desmond Tutu wrote in the forward of the 2008 book “Banning Landmines.” “Such examples offer us hope and inspiration, but we must be very clear that they are the result of determination and hard work … Such examples must be analyzed and studied so that we learn from the lessons they have to offer.”

[Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct cluster munition casualties.]