A message from Homs

Loading...

(Update: Without providing much in the way of details, the British Foreign Ministry said Conroy is leaving Syria. No mention of Edith in the AFP piece, but it's reasonable to assume she'll be leaving with him, however that was arranged.)

The reporters should never be the story. The reporters should never be the story. We're told this when we're starting out by the older and wiser, we tell ourselves this again and again when we think about doing something brave (or stupid, depending on your perspective), and I've been muttering this under my breath following the recent deaths of Anthony Shadid, Marie Colvin, and Remi Ochlik in Syria.

Anthony passed because his asthma caught up with him while being smuggled out of Syria, far from modern medical care. Marie and Remi were killed in a mortar and rocket attack in the Syrian city of Homs, which by the day is looking more like Grozny during the height of the Russian assault on the Chechen capital over a decade ago (the city is even being hit by the same ghastly weapons).

All three of them would agree, were they still here to speak, that their deaths are not the story. Marie's last dispatch for the Sunday Times described a devastated city and in an email to friends described a baby dying of his wounds in a makeshift hospital. Remi, not yet 30, had survived the mortar barrages on the Libyan city of Misrata last year (which claimed the lives of fellow photographers Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros). Anthony's sensitive reporting from Iraq about a nation struggling with the legacy of a brutal dictator and a new war (that we were sadly reminded today is far from over) won him a Pulitzer.

Scott Peterson, who knew both Marie and Anthony, writes for us today about their commitment:

Like most of us who have willingly inhabited the world's war zones, Anthony and Tyler, Marie and Remi, were and are motivated by a powerful impulse to tell the stories of those who suffer and fight under the most appalling circumstances; to shed light into the darkest places.

Speaking at a memorial service for fallen journalists in London in 2010, Marie noted the dangers: "We always have to ask ourselves whether the level of risk is worth the story. What is bravery, and what is bravado?" she said. "Journalists covering combat shoulder great responsibilities and face difficult choices. Sometimes they pay the ultimate price."

But while their focus was on the combatants, and the civilians who bear the brunt of war, it's an inescapable truth that familiar faces and bylines have brought international attention to the escalating war in Syria like never before (I wrote a few weeks ago about how we were all becoming inured to the brutal videos of the casualties there).

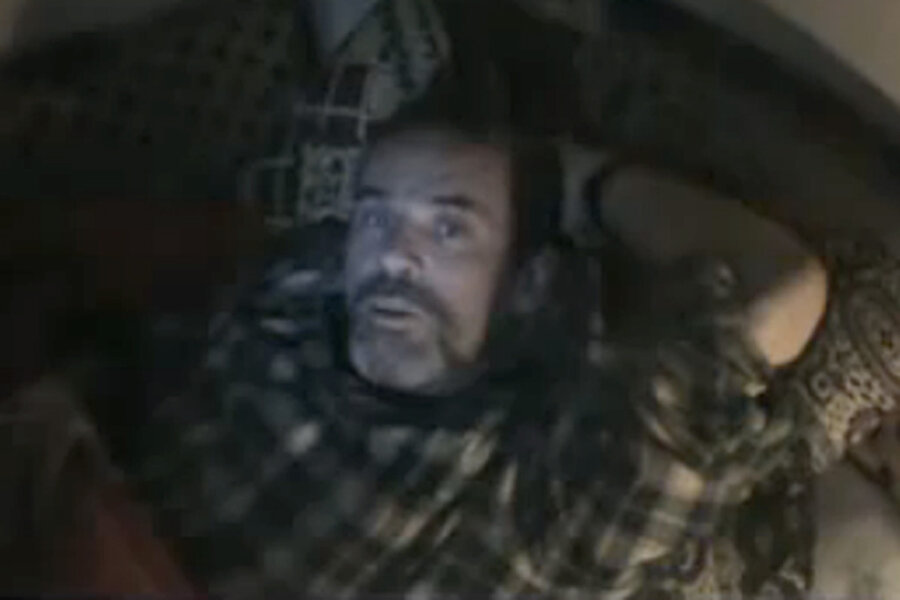

Photographer Paul Conroy was one of the survivors of the attack that killed Remi and Marie. He, and Le Figaro reporter Edith Bouvier, are now trapped in Homs's Baba Amr neighborhood along with its terrified residents, who have been allowed neither safe passage from the area by Bashar al-Assad's troops nor any relief from daily artillery barrages for weeks. Humanitarian organizations and governments have been seeking a ceasefire to extract the journalists, and perhaps the worst of the wounded, with no positive response from Assad's government.

Conroy spoke briefly from the field hospital where he's being treated earlier today. Look at the bare walls, the simple couch that is his hospital bed, the lack of equipment for the earnest young doctor treating him and others. Listen to Mr. Conroy, and remember he isn't the story. There are tens of thousands of Syrians in a similar predicament. But listen.