Jackie Robinson changed baseball 75 years ago. That was just the start.

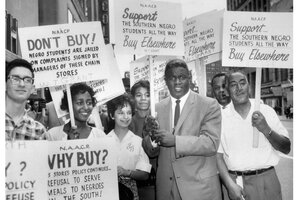

Former baseball star Jackie Robinson grabbed a sign and joined a picket line in Cleveland to protest discrimination against Black people at Southern lunch counters, 1960. The picketing was organized by the NAACP, for which Robinson spearheaded a successful $1 million fundraising effort in 1957, the year he retired from baseball.

AP/File

It is a challenge not to limit Jackie Robinson’s life to a single date – April 15, 1947. On that date, Robinson crossed the color line into Major League Baseball and eventually transformed No. 42 into a symbol of progress.

And yet, Robinson was more than a number, more than a world-class athlete. As a member of the NAACP and a columnist, he was a champion for baseball and for Black people.

“You have made every Negro in America proud through your baseball prowess and your inflexible demand for equal opportunity for all,” Martin Luther King Jr. wrote to Robinson as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in May 1962. King frequently spoke of how Robinson’s nonviolent approach to the integration of baseball inspired him.

Why We Wrote This

Fame often tells an incomplete story. Jackie Robinson is known for breaking barriers in baseball. But he was a champion for civil rights off the field as well.

Robinson made his presence felt in civil rights organizations while still playing baseball, as his 1956 Spingarn Medal awarded by the NAACP shows. He described his civil rights and entrepreneurial endeavors as a way to help Black people attain full citizenship through “the ballot and the buck.”

In 1957, the year he retired from baseball, Robinson spearheaded the NAACP’s Freedom Fund Drive, which raised $1 million for the organization. In 1964, he co-founded and chaired the Freedom National Bank in New York’s Harlem neighborhood, designed to assist African Americans financially.

Robinson famously stole home in the 1955 World Series; 15 years later, he founded a construction company named after him that provided housing for low-income families.

It is remarkable to think of Robinson as an activist and philanthropist. One of his most impactful efforts, the Jackie Robinson Foundation scholarship program, still serves young people of color.

A voice in the Black press

There is a more fiery Robinson, though. The man who often suppressed his anger over baseball’s racism during his playing career found an outlet for that passion as a columnist.

The chronicles of Robinson’s time with the Dodgers were noted in the Black press, thanks to the Pittsburgh Courier and journalist Wendell Smith. Robinson lauded the Black press in his second autobiography, “I Never Had It Made.”

“In a very real sense, black people helped make the experiment succeed,” he wrote, speaking of his commitment to integrate baseball. “I learned that clergymen and laymen had held meetings in the black community to spread the word. We all knew about the Negro press,” referring to their promotion of the idea.

Robinson wrote for the New York Post and the Black-owned New York Amsterdam News. The fact that Robinson sometimes publicly disagreed with both King and Malcolm X is a reflection of the diversity of Black thought during that turbulent time. Robinson’s views on integration put him at odds with the separatism of Malcolm X, and he spoke out against King’s opposition to the Vietnam War.

“A black man in a white world”

Yet despite his influential role in society far beyond the baseball field, Robinson always remembered what it meant to endure as a trailblazer, and he showed those scars in his autobiography. In one excerpt, he described how he felt prior to the first game of the 1947 World Series:

There I was, the black grandson of a slave, the son of a black sharecropper, part of a historic occasion, a symbolic hero to my people. The air was sparkling. The sunlight was warm. The band struck up the national anthem. The flag billowed in the wind. It should have been a glorious moment for me as the stirring words of the national anthem poured from the stands.

But the song didn’t speak to him.

As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.

Up until his death, Robinson pushed to break baseball’s other color lines – in coaching and management. Untiring in his approach to life and baseball, he loved the game with all of his heart, even when it didn’t love him back.