As the Civil Rights Act turns 60, a call to recommit to what it stands for

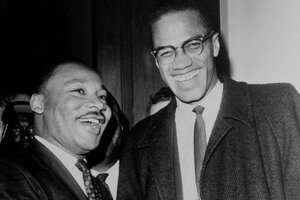

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (left), of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Malcolm X smile for photographers in Washington, March 26, 1964. Several months later, on July 2, the Civil Rights Act became law.

Henry Griffin/AP/File

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 turns 60 on Tuesday. Its birthday is important because it is a living piece of legislation and a predecessor for laws impacting women’s and LGBTQ+ rights.

I can’t help but think about this momentous act and its unifying power and be reminded of the time it brought together two of the greatest men of their generation – Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Their presence encapsulated the urgency of the moment, and the youthfulness that constitutes dreams. And yet, it is hard to see a piece of paper turn 60 while these two men were assassinated just before their 40th birthdays. Their blood, like President John F. Kennedy’s, is proverbially mingled in with the ink that codified antidiscrimination rulings and secured voting protections for Black people. When Dr. King met Mr. Kennedy in March of 1962, they spoke of a “second Emancipation Proclamation.” That promise, in some ways, was fulfilled two years later, though Dr. King’s heartbreaking words from 1968 still endure: “I might not get there with you.”

Why We Wrote This

The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, which turns 60 on Tuesday, represents a lineage of legislation that protects against discrimination. Whether that legacy endures depends on us, our columnist writes.

We are here now, in a maelstrom of court cases and ideological wars that are chipping away at the values and rights we hold so dear. But this has always been the case. The promises of the Civil Rights Act were the promises of Reconstruction – being protected from discrimination, and voting without inhibition or intimidation, among other essential freedoms. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights legislation since the law of the same name in 1875. The Brown v. Board of Education decision, which began with a handful of concerned parents from South Carolina, initiated a series of laws that yielded the landmark civil rights legislation of 1964.

Black activists embraced the urgency of civil rights, which means they represented the best of America. Where even officials such as President Dwight Eisenhower were initially hesitant to push forward on the issue, Malcolm X’s words ring out: “I’m throwing myself into the heart of the civil rights struggle.”

While Malcolm was skeptical of the legislation – he was concerned it would belie how Black folks were treated in America – he was intentional about his fight for freedom. Aside from forming the Organization of Afro-American Unity that same year, he wanted to shift the conversation from “civil rights” to “human rights,” which raised the profile from a domestic viewpoint to an international perspective.

Despite deliberation among advocates, or filibustering from opposing senators, The Civil Rights Act persevered. It wasn’t just a triumph of Dr. King, or Malcolm X, or “Black Cabinet” influencers such as Mary McLeod Bethune. It was a victory for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and activists such as Ella Baker and Stokely Carmichael, who later changed his name to Kwame Ture. It was a victory for past generations of freedom fighters, who witnessed emancipation from chattel slavery, however delayed, only to watch the rise of Jim Crow.

History, for its stories of triumph over oppression, also denotes a cruel reality – those oppressive forces never relent. Even today, the irony of book bans and the dismissal of African American studies in states such as South Carolina is that such restrictive measures are made in the name of “freedom.” But how is it liberating to withhold the stories and legacies of those who fought for a better world?

This is what we are up against in the present hour. Less than a week ago, U.S. Representative Terri Sewell, a Democrat from Alabama, lamented the Supreme Court’s gutting of the Voting Rights Act in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision. A press release from Representative Sewell’s office notes this harrowing fact from The Brennan Center For Justice: At least 31 states have passed 103 restrictive voting laws since the Shelby decision.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, along with the Voting Rights Act of the subsequent year, are perhaps the two most important legislative flashpoints of the time period, and in this country’s civil rights history. Conversations about their legacy should include champions as well as opponents. Our failure to tell these stories with accuracy and regularity are part of the reason why battles over fundamental rights wage on.

We should approach them as Malcolm X did – by throwing ourselves into the heart of the struggle. Civil rights, quite simply, are the fulfillment of our independence: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Denying them is to deny America itself.

According to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, when the civil rights bill passed the Senate in 1964, “King hailed it as one that would ‘bring practical relief to the Negro in the South, and will give the Negro in the North a psychological boost that he sorely needs.’”

I would contend that a recommitment to civil rights, 60 years later, would be relief and refuge for us all.