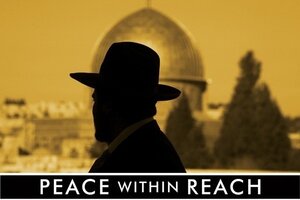

A holy city's peaceful purpose

Centuries of religious tension in Jerusalem must yield to an inspired vision.

While revolt across the Arab world makes the process of peace talks between Israelis and Palestinians less certain, it makes their outcome more urgent. Can the revolutionary spirit sweeping the region open the door to fresh ways to resolve the Middle East’s most troublesome conflict? This is the third essay of "Peace within Reach," a three-part commentary series that explores why peace may be closer than you think.

Photo Illustrations by John Kehe/Staff; Photos by AP

St. Paul, Minn.

To the Gospel writer John, it was "the great" and "holy" city. To the writer of Hebrews, it was "the city of the living God." To the poet Dante, it was "the city where God dwells and reigns."

Of Jerusalem it is safe to say that no city has ever been the object of such heavenly visions – or such earthly discord. At the confluence of the world's three great monotheistic faiths – Judaism, Islam, and Christianity – Jerusalem has long been, in the words of author David Shipler, "an arena for the conflict of certainties." Faith, politics, and the promise of salvation converge in Jerusalem to produce unyielding emotional and spiritual attachments that test the very limits of peacemaking.

At issue is whether Jerusalem is to be the undivided capital of Israel, the home of two capitals in the event of Palestinian statehood, or the object of international jurisdiction.

Deep attachments to sacred space

For a place where God is presumed to be so immanent, religious history has proved more a barrier than a bridge to peace.

It was here that David united the disparate tribes of Judea and Samaria into a united kingdom. It was here that Jeremiah thundered against the backsliding of the Jews and called for a more exalted worship of God. It was here, atop the Temple Mount, that Solomon built the first great Jewish temple, and where, centuries later, Herod built another.

And it is Jerusalem – the city and the ideal – that provided the most durable symbol of unity for the millions of Jews forced into 2,000 years of exile after Herod's temple was destroyed by Roman legions in AD 70. For Israelis, history leads to only one conclusion: Jerusalem belongs to the Jews.

Not so, say Palestinians, who reject Israel's demand for exclusive control of Jerusalem. The ancestral roots of today's Palestinians precede the Jewish presence in Jerusalem, they insist. For 14 centuries, Jerusalem has been one of Islam's holiest sites. Islamic tradition has it that it was from the Dome of the Rock, a shrine erected on the spot where the temples of Solomon and Herod once stood, that the prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven one night to talk with God.

The unique hold Jerusalem has on the religious imagination is reflected in the concept of sacred space. Jews believe that Jerusalem is where divinity comes closest to humanity. Muslims believe that any good deed done in Jerusalem has a thousand times the normal weight, while any sin, a thousand times the gravity.

Such deep attachments have magnified the impact of historical injustices, ancient and modern. Israelis remember with considerable bitterness that between 1948 and 1967, when Jordan controlled the Old City of Jerusalem including the Temple Mount, they were barred from the holy places, some of which were desecrated. For Jews, this is the ultimate argument for maintaining exclusive control of Jerusalem. Just as bitterly, Arabs complain that Israel has seized entire Arab neighborhoods in Jerusalem and replaced them with their own, in violation of international law. For Arabs, this is the ultimate argument for demanding that the city be divided into Arab and Jewish jurisdictions.

The question that hangs over any future negotiations is whether the dead weight of history can be lifted sufficiently to arrive at a compromise and to preclude the often-discussed possibility – still considered remote – that the United Nations or some coalition of powerful nations would define the "final status" of Jerusalem on their own, perhaps by internationalizing the city.

Pessimism and cynicism come easily in the city, whose disposition has posed the biggest stumbling block to peace – meaning that, to succeed, aspiring peacemakers may need to embrace a broader frame of reference.

The city has long been the object of religious nationalism and proscriptive theology. But in a larger sense, it has also been a repository of the highest aspirations and ideals of the generations of Jews, Muslims, and Christians who have lived in or made pilgrimage to this holiest of cities. It is a place where the deeds of prophets, teachers, and disciples have proclaimed history's grandest moral lessons.

'Founded peaceful'

In the end, it may be the very concept of Jerusalem itself that will redeem the city from its long history of strife. It is a concept hinted at in its name, from the ancient Hebrew meaning "founded peaceful." It draws its essence from and bears the mark of the holy men and women who have trod its narrow streets, preaching, teaching, healing, and, in different ways, defining the exalted aspirations that make peace the city's logical final status.

The cycles of violence and recrimination that mark the history of Jerusalem and the wider Arab-Israeli conflict have been abetted by the devotion of both sides to the ethos of "an eye for an eye." Over the years, Christians have urged acceptance of the lessons of forbearance and forgiveness taught by Christ Jesus in the very streets of Jerusalem.

Many Jews and Arabs have been articulate advocates not only of mere peaceful coexistence but of something much more: the empathy that comprehends the circumstances of an adversary. And not among peace groups alone do such views surface. Several years ago, a former head of Israel's internal security service drew a burst of attention by criticizing the government's handling of relations with Palestinians living under Israeli occupation. "If we do not begin to understand the other side," he said, "we will not get anywhere. We must, once and for all, admit that there is another side, that it has feelings, and that it is suffering...."

A central question hovering over on again, off again peace talks is whether this is a voice crying in the wilderness or the voice of the future.

The point, peace advocates argue, is not to sacrifice vital national interests, but to understand that no long-term national interest can be served when relations between Arab and Jew are governed by doctrines that sanctify retaliation. Weighing in the balance are powerful forces of religious extremism: Muslims, especially in Gaza, who continue to call for the elimination of the Jewish state; and Jewish extremists, concentrated in the "settler" movement, who systematically and with government support expropriate Arab land in the West Bank.

Perhaps the underlying fears of both reflect the insecure sense of national identity of Palestinians, who have never had a state, and of Jews, surrounded by often-hostile Arab nations, whose sense of national identity has always been fragile.

Three questions we must answer

The apostle Paul once defined Jerusalem as "the mother of us all." It is unlikely that any peace that fails to accommodate the fact of Jerusalem's unique status in the eyes of the world can survive. History and religion have imposed their heavy, arguably unsustainable burdens on Jerusalem and on the long string of diplomats who have striven to lift it. Nevertheless, three persistent questions posed by the prophet Malachi, inconvenient to extremists on both sides, remain to be answered by all the protagonists in the long contest between Arabs and Jews: "Have we not all one father? Hath not one God created us? Why do we deal treacherously every man against his brother...?" Answered aright, "the joy of Jerusalem" that Nehemiah once proclaimed will once again be heard, "even afar off."

George Moffett is a former Middle East correspondent for the Monitor.

Editor's note: This is the third essay of "Peace within Reach," a three-part commentary series about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.