Moonbase Alpha: New NASA game lets you run a virtual lunar station

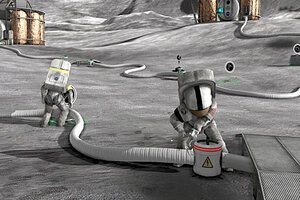

Moonbase Alpha has players working together to restore oxygen flow and critical systems on a virtual lunar base after a meteor strike.

Developed by NASA, Moonbase Alpha lets players step into the role of a lunar astronaut.

Screenshot from moonbasealphagame.com

NASA may not be sending astronauts back to the moon anytime this decade, but the space agency hopes to give virtual explorers a sense of what life on the moon would be like in a new computer game launching this month.

The game, "Moonbase Alpha," will allow players to work together in a futuristic lunar base. It will be available for PC download from Valve's Steam network on July 6. Players must tackle the challenge of restoring oxygen flow and critical systems after a meteor strike cripples a solar array and life support system.

This comes as a precursor to NASA's massively multiplayer online game, called "Astronaut: Moon, Mars & Beyond," where players would take on astronaut roles, such as a roboticist, and explore virtual versions of the moon and other extraterrestrial locations. [Video: Moonbase Alpha trailer]

IN PICTURES: Controversial video games

NASA and the game developers had debated about whether to keep the "Moonbase Alpha" setting on a lunar base, after the cancellation of NASA's Constellation Program that aimed to return astronauts to the moon. But they eventually decided to forge ahead with their original plans.

"The moon's not going anywhere," said Daniel Laughlin, project manager for NASA Learning Technologies at the agency's Goddard Earth Science and Technology Center in Maryland.

A game of their own

Games that recreate real space environments inside a user's computer can entertain casual gamers and perhaps spread the word about space exploration activities. At least that's the hope among NASA's "Moonbase Alpha" designers, and the U.S. space agency isn't alone in trying to tap into that potential.

Consider: If paying $200,000 for a real-life suborbital spaceflight on a Virgin Galactic space liner sounds like a hefty price, that ticket price still falls short of the $330,000 one gamer spent to buy a virtual space station in the online game "Entropia Universe."

The company behind "Entropia Universe" has since created a demo for the European Space Agency (ESA) to show how online gaming could promote space exploration.

The developers at MindArk used their "Entropia Universe" game engine to create a virtual base set on Jupiter's moon Europa. Their scripted demo shows players cooperating on in-game missions, such as repairing a broken-down rover

"[ESA] was expecting a mock-up, but not a prototype," said Christian Bjorkman, chief marketing officer for MindArk. "But for us to create the mock-up, we might as well create the environment and run around in it."

But Joachim Fuchs, a technical officer and system modeler at ESA, had also seen examples of engineers holding collaborative work sessions in online games. He wondered if an online game could not only promote space exploration among gamers, but also allow engineers to play out scenarios for future space missions.

"The next generation of engineers we're going to get in this agency is going to have grown up in a world dominated by [gaming] technologies and social networks," Fuchs told SPACE.com.

To educate or entertain

Massively multiplayer online games have attracted millions of players worldwide who are willing to pay about $15 per month to run around a virtual world with thousands of other people. Researchers have even looked into using popular games such as "World of Warcraft" to encourage group learning among students.

That doesn't mean NASA and ESA can simply cram knowledge down the throats of gamers. Successful online games provide players with entertainment first and foremost — a fact that both the U.S. and European space agencies have recognized.

NASA has recruited the help of game developers such as Virtual Heroes, which created the free online game "America's Army" for the U.S. Department of Defense. The U.S. Army has dubbed the game its single most effective recruitment tool for reaching out to young people.

"America's Army" works because most of it feels like any other action-oriented, shoot-'em-up game. Yet it also immerses players in virtual Army training, such as learning how to use different weapons on the firing ranges, or diagnosing and treating virtual wounded soldiers.

Games that advertise their intent to educate players and promote learning have fared less well, according to the MindArk developers. They also emphasized the need to create a self-sustaining, profitable game that players would want to keep playing.

"The absolute majority of these educational games have been a failure in terms of attracting the interest and keeping it among the kids," Bjorkman explained. "This means that the fundamental criteria should always be to have an entertainment base in which learning factors are built upon and added to."

Exploring the virtual frontier

ESA considered many software and game developers to examine the idea of an online game, but ultimately chose MindArk based on its success with "Entropia Universe." The commercial game allows players to pay real money for better in-game guns or equipment, but players can also earn virtual game currency and then cash out for real money.

MindArk already offers commercial partners the choice of adding on new planets to "Entropia Universe," making it easy to put together the Europa base demo.

"In the ESA study our game developers could put together the prototype environment in a short time and publish the finished 'game' for ESA to access and evaluate; it is actually still online," Bjorkman said.

The study suggested several game development scenarios for an ESA-themed game, depending on the space agency's goals. An online game with fewer players could represent a more suitable choice for exploratory learning. Another game could reach out to more casual players through social media, but at the expense of education.

ESA has yet to decide on a full-fledged game, and has not signed any developers on. But both ESA and MindArk representatives were enthusiastic about the possibility of pushing forward.

"Increasing the awareness and knowledge about space are issues far too important NOT to be played out in a game," the ESA study concludes.