Obama on justice: Could gentler exit from prison halt the revolving door?

While visiting a drug treatment center in Newark, N.J., Monday, President Obama is expected to announce steps to help formerly jailed and imprisoned people re-enter society.

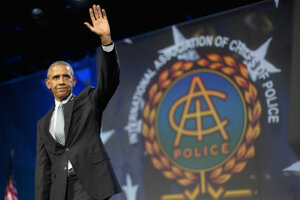

President Obama waves after speaking at the 122nd International Association of Chiefs of Police Annual Conference in Chicago on Oct. 27. Mr. Obama on Monday will appear in Newark, N.J., where he is set to announce steps to help formerly incarcerated people re-enter society.

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

As part of a broader effort to make criminal justice reform a priority of his final years in office, President Obama on Monday will unveil steps to help former inmates re-enter society.

The actions, which Mr. Obama will announce at a speech in Newark, N.J. , are part of a national conversation about justice, race, and violence in America that has been driven by outrage over racism and the use of excessive force by police. These White House moves also mark a shift in tone from previous presidents and politicians, who over the last few decades have been less concerned about being too hard on criminals than being too soft on crime.

“I believe we can disrupt the pipeline from underfunded schools to overcrowded jails,” Obama said during his weekly address Saturday. “I believe we can address the disparities in the application of criminal justice, from arrest rates to sentencing to incarceration. And I believe we can help those who have served their time and earned a second chance get the support they need to become productive members of society.”

The steps would include new guidelines regarding the use of arrest records in qualifying for assisted housing, and the allocation of up to $8 million for education programs for formerly incarcerated people. The president is also instructing the Office of Personnel Management to put off any inquiries into applicants’ criminal backgrounds until later in the hiring process.

"While most agencies already have taken this step, this action will better ensure that applicants from all segments of society, including those with prior criminal histories, receive a fair opportunity to compete for federal employment," the White House said in a statement.

It’s a marked change from discourse in the late 1980s, when Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, the Democratic nominee for president, was all but blamed for the crimes of Willie Horton, a convicted murderer who committed assault, armed robbery, and rape while out on a weekend furlough. By the mid-1990s, President Clinton was calling for "the toughest crime bill in history” and appealing to Congress to help him "reclaim our streets from violent crime and drugs and gangs."

The result was a spike in the prison population; today, the United States accounts for only 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prison population, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

"There was an inclination in the old days to get tough, or at least not be a leader on this [criminal justice] issue,” Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, a Washington, DC-based nonprofit that advocates for sentencing reform, told the Associated Press. “Now I think it's much safer politically. Nobody is going to lose an election based on crime policy like they might have once.”

In July, Obama became the first sitting president to visit a federal prison. He has called on Congress to overhaul sentencing laws to to help cut the population of people serving long sentences for nonviolent drug crimes. And he has made it a point to identify both with police and the people being policed.

Speaking to law enforcement in Chicago last week, Obama said, "There were times when I was younger and maybe even as I got a little older, but before I had a motorcade – where I got pulled over.”

"Most of the time I got a ticket, I deserved it,” he added. “I knew why I was pulled over. But there were times where I didn't."

Some political opponents have criticized the president for his position on policing. At last week’s GOP primary debate, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie raised Obama's remarks to police, saying, “When the president of the United States gets out to speak about it, does he support police officers? Does he stand up for law enforcement? No, he doesn't.”

Some experts, however, note that while recent efforts to reform the country’s policing and criminal justice systems have not yet been in place long enough for them to have any measurable impact on police behavior or incarceration rates, they have made it clear that change is in the air.

The whole conversation about policing has changed dramatically. We have a huge opportunity to make some real changes,” said Samuel Walker, a criminologist who has been studying policing for the past four decades, to the Monitor. “We have a lot of very good ideas that are out there. And the public understands these problems in a way that has not been true in the past.”

This report contains material from The Associated Press and Reuters.