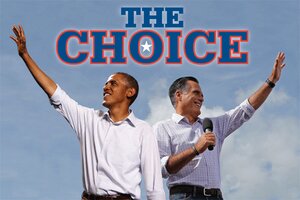

Election 2012: How another Obama term might be different

Would four more years of Obama change the Washington dynamic? A two-part election 2012 report profiles the stark differences and interesting similarities of a second-term Obama White House vs. a Romney White House – either of which would have to deal with a highly polarized Congress.

This two-part cover story for the Oct. 15 issue of The Christian Science MonitorWeekly looks here at how a second-term Obama White House might be different, and in a companion article at how Romney White House might operate.

Staff illustration

Washington

Suppose President Obama wins reelection and the Republicans win control of at least one house in Congress. In other words, the status quo prevails.

Are Americans, therefore, in for four more years similar to the past two, defined by intense partisanship and gridlock? Or would Mr. Obama's reelection change the dynamic in Washington and pave the way for compromise?

Obama is asserting the latter. By definition, he has said in recent interviews, being reelected will put to rest Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell's priority of making Obama a one-term president, and will add new fuel to Obama's agenda – to lock in place health-care reform, raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans, and cut subsidies for oil companies, to name a few of his goals.

"The American people will have spoken," the president told The Associated Press.

It is that vote of confidence, Obama hopes, that will bring Republicans back to the table ready to make a deal – not just on the critical "fiscal cliff" issues that must be resolved by the end of the year, but also toward a "grand bargain" on deficit reduction: spending cuts, including on entitlement programs such as Medicare, in exchange for Republican concessions on revenue.

But it remains far from clear just what kind of mandate, if any, Obama will have gained from reelection, especially if he wins by a slim margin. After all, the Republicans – having lost the presidential race – will probably be embroiled in their own internal battles over the future of their party, and may be in no mood to give ground to a newly energized Democratic president, just as they weren't in the mood in January 2009 after Obama's first inauguration.

"Any kind of dream that it will be 'Kumbaya' up there and that gridlock will suddenly end and Republicans will work with him, that ain't happening," says Democratic strategist Peter Fenn.

But that doesn't mean Obama would give up. Far from it. During his first presidential campaign, in an interview with a Reno, Nev., newspaper, he portrayed himself as a Reaganesque figure who could change the trajectory of America. President Reagan, Obama said, "tapped into what people were already feeling, which was, we want clarity, we want optimism." The senator from Illinois suggested he would do the same.

Early in his presidency, Obama swung for the fences – and succeeded, against the odds, in passing the Affordable Care Act, despite the economic emergency he inherited and that still threatens his reelection amid lingering high unemployment and sluggish economic growth. A second term would present more opportunity for bold action, though more on Republican terms than when he first took office.

"This is a guy who came in here wanting to do big things," Mr. Fenn says. "Everybody thinks he's wedded to some labor union or some senior citizens organization or some environmental group, but if they think he's going to knee-jerk his way through a second term, I don't think so."

And as much as Republicans insist a reelected Obama would feel free to let his true "leftie" self run wild (since he won't face voters again), the more probable scenario is that he would feel less constrained by his liberal base and would be willing to cut deals with the Republicans, analysts say.

"He may end up really ticking off folks on the Democratic side," says Fenn.

Obvious opportunities for dealmaking early in Obama's second term would center on deficit reduction and tax reform. But voters wouldn't know that from the campaign. Both Obama and Republican challenger Mitt Romney have only outlined goals, staying vague on details and allowing each to spin the other's plans in equally unappetizing ways.

The better bet is to read Bob Woodward's new book, "The Price of Politics," which shows how far Obama was willing to go in the grand bargain negotiations of summer 2011 – particularly on the restructuring of Medicare, the biggest driver of the nation's unsustainable fiscal path.

According to Mr. Woodward, Obama and House Republicans were willing to raise the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 67, but couldn't agree on how quickly to phase in the change. Another negotiation, between Vice President Joe Biden and House majority leader Eric Cantor, contemplated higher premiums for wealthier seniors.

In 2013, just as a reelected Obama could feel freer to negotiate on deficit reduction, so, too, could congressional Republicans – widely expected to retain control of the House, though with a smaller majority – claim a voter mandate to keep taxes low. But there are lots of moving parts: How much leeway each side would have, given the demands of their respective caucuses, is impossible to predict.

"I'm not deeply optimistic here, I must say," says Norman Ornstein, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. Still, he paints a scenario in which a reelected Obama enjoys "considerable leverage" in December, during a lame-duck session of Congress, when the nation reaches its so-called fiscal cliff. At the end of 2012, a package of tax increases and dramatic spending cuts are due to take effect, threatening another recession, if agreement isn't reached.

"Obama can go to Republicans and say, 'Look, if you guys insist on this, then I'm going to hold firm, and we'll let the fiscal cliff be reached,' " says Mr. Ornstein.

Obama, in that case, could go to the American people and explain the situation – how another recession could result, but how he would also be empowered to address the nation's long-term debt and deficits, Ornstein says. And, he adds, expect Obama to make greater use of the bully pulpit this way.

It's also possible the lame-duck Congress would pass a short-term fix and leave solving the fiscal cliff to the new Congress. But the longer urgent fiscal issues eat into Obama's second term, the less time he would have for other priorities, beyond tax and entitlement reform.

Comprehensive immigration reform is one area where analysts see possibility for new action. If Obama is reelected, it's likely that Mr. Romney would have done poorly with the Latino vote – creating a GOP urgency to retool its approach to this fastest-growing segment of the electorate. Obama, too, is under some pressure to deliver with a reform that goes beyond his stopgap measure halting deportations of some young illegal immigrants.

Along with his inability to close the Guantánamo Bay prison camp, Obama's failure to enact immigration reform is his biggest unfulfilled campaign promise. In a recent appearance on Spanish-language Univision TV, journalist Jorge Ramos grilled Obama over the issue, and Obama said: "As you remind me, my biggest failure is that we haven't gotten comprehensive immigration reform done. So we're going to be continuing to work on that. But it's not for lack of trying or desire."

But given the urgent fiscal issues up first, it's not clear that Obama and the Republicans will get to it. Nor are prospects high for major initiatives on other lingering matters, such as climate change and energy policy. In an interview with Grist magazine, Obama's former climate czar, Carol Browner, suggested that a "sector-by-sector approach to reducing greenhouse gases" might have more success than one big bill.

The reality of second-term presidents is that they struggle to achieve big things and, by the last two years, end up focusing on foreign policy. Upon reelection, President George W. Bush declared he had a mandate to reform Social Security, and got nowhere. Obama may have to settle for protecting the biggest initiative of his first term: health-care reform. Or he may look at the legacy of Reagan, who did have a productive second term on both domestic and foreign policy, and swing for the fences once again.