'The Spectacle of Skill' reminds us how dazzling critic Robert Hughes could be

Loading...

The late Australian-born art critic, historian, and TV documentary-maker Robert Hughes could be unpredictable when encountering a new work of art.

Sometimes he would lay one sausage finger across his lips and stare at the thing, whatever it was (painting, sculpture, installment, even outfit), his head tilted slightly downward, the very image of the Fifth Avenue connoisseurs whose pretensions he so readily mocked. Far more often, he would seem not even to notice the new work of art; he'd continue with his stream of cheerful talk, maybe make a casual comment or two, and it would only be hours later, over dinner or drinks, that the work would finally register with him – and fill the next four hours of excited discussion.

That such a register-moment took a second place to human conviviality made him great company; that it would certainly, inevitably happen made him a great critic. As Adam Gopnik writes, “Robert Hughes was many things, but he was never a meta-thing. He was the real thing: living and breathing and red with exertion and, sometimes, rage.”

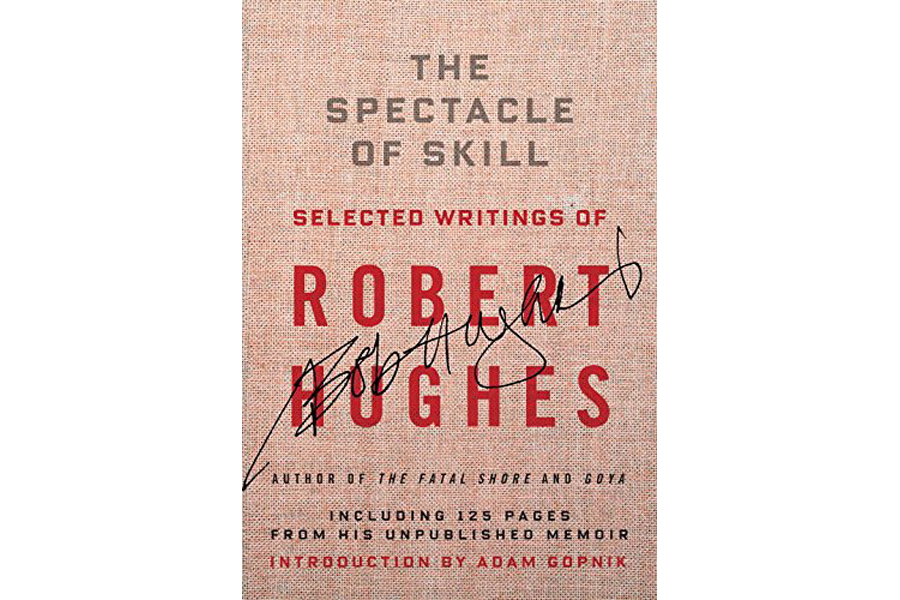

Gopnik's comment is part of his brightly perceptive Introduction to The Spectacle of Skill, a new posthumous volume of the writings of Robert Hughes. For those who knew the man or knew his work, there could scarcely be any sadder words in English than “a posthumous volume of Robert Hughes,” but Gopnik is surely right to set such a warm and inviting tone to this collection. Hughes wrote many kinds of things in a career that spanned four decades – history, commentary, criticism, journalism – but his primary goal was always the same: to entertain, especially while he was educating.

"The Spectacle of Skill" will serve as a generous reminder to all those familiar with Hughes's prose of just how dazzlingly he succeeded at that goal, and it will introduce newcomers to one of the great critical voices of the late 20th century.

The collection itself is a trifle odd. It consists of two excerpts from 1981's "The Shock of the New"; three pieces from his 1987 history of Australia, "The Fatal Shore"; nine essays from his brilliant 1991 anthology "Nothing If Not Critical,"; four excerpts from his 2001 piece of travel-writing, "Barcelona,"; three excerpts from his 1998 tour d'horizon of American art history, "American Visions,"; three sections from his 2004 appreciation "Goya,"; five from his 2006 memoir "Things I Didn't Know,"; two chapters and the prologue from his 2011 book "Rome,"; and eleven segments from an unfinished memoir.

The critical essays from books like "The Shock of the New" or "Nothing If Not Critical" aren't the odd part, naturally; they're hard, glittery gems as perfect now as when they were crafted years ago for such periodicals as "The New York Review of Books." But the excerpts from longer works sometimes seem quickly or even randomly chosen, and some of them have been snipped and massaged a bit by an unknown hand (the volume lists no editor). Likewise odd is the long chunk of that final memoir. Some of its segments are far more polished than others – indeed, some are almost sloppy. Yes, the thing is billed as “unpublished,” but much of it also often feels unready, which makes it an odd capstone to the publishing history of such a perfectionist as Hughes.

Fortunately, that perfectionist hardly ever published a sentence that isn't worth re-reading, and "The Spectacle of Skill" is crowded with that particular kind of spectacle. About John Singer Sargent: “Sixty years after his death, his “paughtraits” (as Sargent, who kept swearing he would give them up but never did, disparagingly called them) provoke unabashed nostalgia.” About the death of Jackson Pollock: “Pollock became Vincent van Gogh from Wyoming, and his car crash – the American way of death par excellence – was elevated to symbolism, as though it meant something more than a hunk of uncontrolled Detroit metal hitting a tree on Long Island.”

Even the uneven memoir-fragment contains some some very touching reflections about his son Danton, who would eventually commit suicide but whose boyhood excursions to the beach (down a thicketed pathway “like a detail of a Courbet”) are recounted in hues of pure sunlight: “to the beach, Danton prancing and laughing in front of us, then running up to grab my hand. How I loved him, and at that moment, at least, I was finding out how to be a father, and it made our life so simple.”

It would be sad to think this volume is the last we'll see of Robert Hughes, sad especially if his punchy, eternally wise art criticism were allowed to fade away. Throughout his life he echoed the precept of Baudelaire: “Je resous de trouver le pourquoi, et de transformer ma volupte en connaissance” – I made up my mind to find out the why of it, and to change my pleasure into knowledge. He succeeded enormously in this, and if Knopf were to follow this “Selected Prose” volume with a “Collected Essays,” we'd all be the better for it.