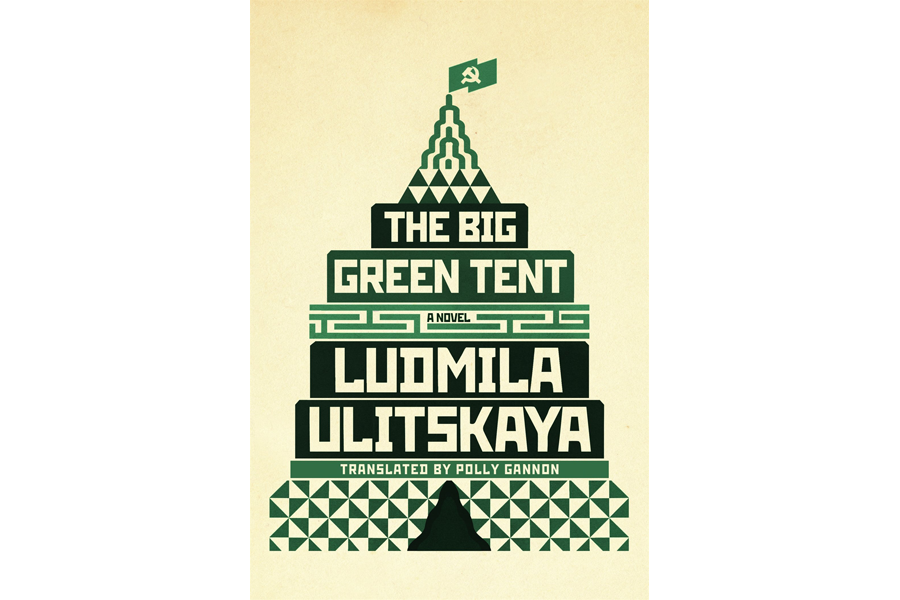

'The Big Green Tent' wraps history and literature into a very Russian story

Loading...

Despite being out of favor with President Putin’s minions, the amused and gracious Ludmila Ulitskaya is, since the demise of the Soviet Union, the most highly awarded literary artist in Russia. Her novels and story collections have sold millions. Now, in her latest novel, she pegs the center pole of her big tent of a story in Moscow in 1953, when the ogre Stalin died and her heroes and heroines, born in the last year or two of World War II, were in grade school.

Born in 1943 herself, to non-religious Jewish parents in Ufa, 700 miles from Moscow, Ulitskaya is fond of her creations, with whom she seems familiar in the way one is with friends; she knows their parents, their pasts, their awkward adolescences, their educational and artistic ambitions and failures, their loves and losses, their admirable pluck and their ridiculous idealism, their weary concessions or principled resistance to forces too strong for any Soviet citizen to withstand. We get to know, from a smiling observer’s distance, her budding heroines Olga, Tamara, and Galya, and her budding heroes Mikha, Ilya,and Sanya. Some of them become creative artists, some of them are Jewish (a designation marked on their passports for possible use against them).

All of them run up against walls in their schooling or careers in the USSR. Some of them emigrate. All of them suffer. All of them are distinct in their roles, even if not always vivid.

Privileged and brave Olga plays the biggest role, but it’s Afanasy, her father, a retired general, whom we meet as he putters in his carpentry workshop, who steals every episode in which he appears. Though disapproving of Olga’s conduct in her marriages, his only regrets, we learn, are the woes he caused the love of his life, his former secretary and mistress: “He only knew she was a goddess. And he worshipped her. He was never plagued by the trifling thought that he might be betraying his wife. His wife was one thing; Sophia was another. Completely other. And if she hadn’t turned up in Afanasy Mikhailovich’s life, he would never have known that love was sweet, or what a woman was, and what profound solace she could bring to the troubled life of a builder.”

In 1949, more than a dozen years into the affair, he cowardly consigned Sophia to prison (her siblings, actors in the Jewish theater, were suspected of anti-Soviet sentiments). Four years later, after her release, they resume the affair: “And all their former closeness returned, even more intense than before – for they had lost each other forever, and found each other again by chance.

“And the second part of their double-feature true-love movie began. One thing, it goes without saying, had changed. They never talked about work.”

Ulitskaya’s easy-going manner and sense of humor are attractive and it doesn’t take long to trust she knows what she’s doing. But this is not a friendship novel in the mode of Elena Ferrante’s. Where Ferrante is intense and demandingly absorbing, with Ulitskaya it’s as if the author has sat us across the kitchen table from her, over tea and cookies, and begun reminiscing. She starts and ends, fills in middles, remembers an experience through the eyes of another character. She criss-crosses.

We can’t see the quilted patterns until we start reencountering characters whose deaths we have already heard about or witnessed, but now they’re younger and alive. She surveys their long lives, savoring their childhoods and sympathizing with their middle-aged difficulties. To a storyteller, fate is simply knowing what’s going to happen before it does. “It’s incomprehensible, improbable – but the generosity of fate also extends to the likes of these C list extras,” she reminds us in a typically confiding aside. She applies what I like to call the Tolstoy-rule: Everybody’s life is, to him- or herself, a novel in itself.

Ulitskaya was a geneticist after college before soon losing her job for distributing samizdat, the hand-copied literature that disaffected truth-loving Soviet citizens disseminated at the risk of arrest and prison. Her characters also participate in this dangerous activity, which was made famous in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s post-exile memoir, "The Oak and the Calf."

As "The Big Green Tent" proceeds forwards and backwards and sideways through time and space, Ulitskaya dips us back into a history lesson now and then. It may be about the Khrushchev era. Or it may segue into the story of Boris Pasternak’s Nobel Prize in 1958, which led to his being denounced by the government. Or it could focus on "The Gulag Archipelago," Solzhenitsyn’s indictment of the USSR labor camp system, a portion of the manuscript of which is, in Ulitskaya’s unlikely telling of a possibly true event, accidentally and fortuitously spirited away, during a KGB search, in a boot. Ulitskaya takes up history not as in "War and Peace" or other epics but quietly, as it consequentially collides with the private lives of her crew.

She, her own narrator, reflects, “we live not in nature, but in history”; her sense of Russian history is her country’s glorious literary past: “And Pasternak walked down this very lane twenty years before. And one hundred fifty years ago – Pushkin. And we are walking down it, too, skirting the eternal puddles.”

For her and her heroes, literature is, if not the purpose of life, then its moralizing center: “A small but mighty army of young people had learned the art of reading Pushkin and Tolstoy. Victor Yulievich [the influential teacher of her heroes in their adolescence] was certain that his students were thus inoculated against the ills and evils of existence, both petty and grand. In this he was, perhaps, mistaken.” The translation, by Polly Gannon, is light and lively, wonderfully devoid of accent or awkwardnesses. (Another reader will have to check it against the original 2010 Russian publication.)

For all the novel’s reach and extension, however, there’s a hastiness that is perplexing: Ulitskaya occasionally but abruptly loses interest in one character or another, and then, practically yawning, she dashes off elsewhere. It’s not that she’s partaking in that familiar Tolstoyan scene-switching or in Dostoevskian power-driving and cliff-hangers; bored or her imagination having flagged, she’ll suddenly summarize a decade of a hero’s life in a paragraph.

But after all, these are her friends!, and their lives in their entirety can’t continuously fascinate her. She concludes her acknowledgements page with a testimonial that American authors, perhaps leery of lawsuits, almost never acknowledge: “Finally, with gratitude, I would like to remember the dear departed who have served as the inspiration for my characters, the innocents who stumbled into the meat grinder of their time, those who survived, and those who were maimed; the witnesses, the heroes, the victims – in their eternal memory.”