His father fled China. It took years for him to talk about it.

The desire to know one’s roots runs deep across most cultures. For Edward Wong, a diplomatic correspondent for The New York Times, learning about his Chinese ancestry has particular resonance. He can trace his origins back more than 30 generations.

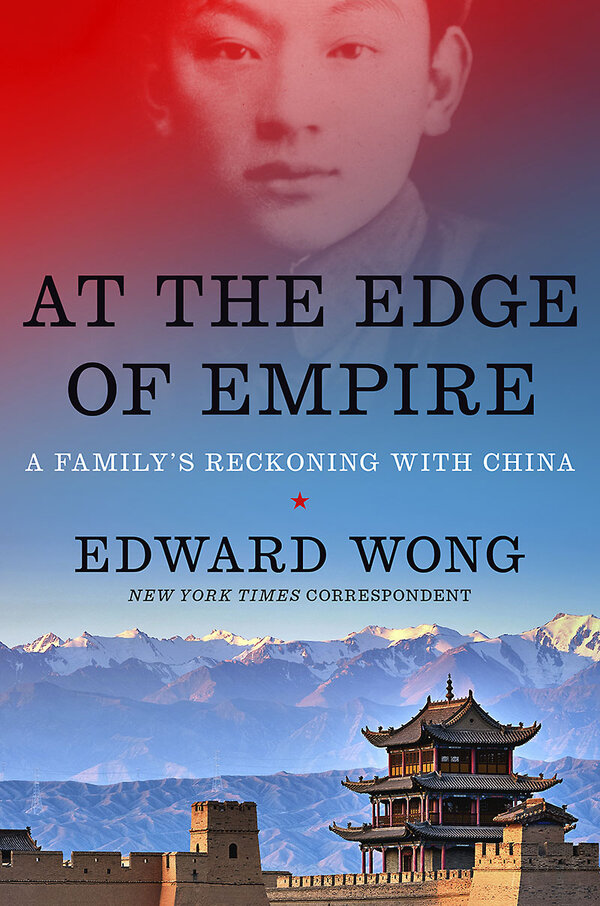

In “At the Edge of Empire: A Family’s Reckoning With China,” Wong investigates his father’s life and the events that led his father to flee China in the 1960s, before Wong was born. Wong is also eager to compare his father’s lived experience with the China that Wong witnessed as a journalist in Beijing for the Times from 2008 to 2016 – the last two years as bureau chief. The result is a multifaceted, deeply personal, and moving account that helps us understand how China has evolved.

Yook Kearn Wong, the author’s father, was born in Hong Kong in 1932. When the Japanese conquered the British colony at the outbreak of World War II, he moved, along with his family, to his ancestral village in southern China. He survived the Japanese occupation and finished high school in 1950, just after the Communists seized control of the country. Wong’s father quickly embraced the Communist cause and moved to Beijing to attend college in hopes of being part of the effort to build a new China.

Once again, war disrupts Wong’s father’s life. When China enters the Korean War, he drops out of school to join the air force. He enthusiastically completes basic training. But he is stunned to be rejected – without explanation – from enlisting in the air force. Instead, he is sent to the army and assigned to a series of increasingly remote outposts in the country’s northwest provinces.

It dawns on Wong’s father that the family’s connections to Hong Kong and to the West (his brother was then a university student in Washington, D.C.) have placed him under government suspicion. He resolves to rededicate himself to the Communist cause, but as his hopes for advancement and a life of purpose diminish, he begins to see how the party’s efforts to create a new China produces failures that kill millions of people.

Wong’s father, determined to flee China, devises a plan that involves fooling the Chinese authorities about his health, obtaining permits to leave China through a family friend, and offering some timely bribes. Carrying only a small bag of clothes and some opera albums, Wong’s father arrives in Hong Kong in January 1963. Before long, he moves to the United States with a wife he met before leaving, settles near Washington, and works in a Chinese restaurant for 23 years.

The author’s family does not really discuss his father’s past. It is only as Wong becomes a graduate student and a foreign reporter that he starts to ask his father questions about China. After the author moves to Beijing, he visits the places where his father lived. Wong feels “like I was a phantom shadowing him through the decades, an echo of his earlier presence.”

The story is largely chronological, and the chapters on his father’s life are compelling: One can feel Wong’s father’s illusions being stripped away as he continues to – in the eyes of the party – fall short. Wong is a careful and insightful observer in describing his own time in China, but those chapters are choppier and less well integrated. Interestingly, Wong’s mother does not feature much in the story. One suspects there is another compelling account that could be told about her life.

China today is assertive, aggressive, and expansionist. Wong lays out the ways that China seems intent on challenging the U.S. This is not new. Still, “At the Edge of Empire” is a valuable reminder that China’s goals haven’t changed in 75 years.