Unmasking Elena Ferrante: why privacy matters

Loading...

She's an award-winning, bestselling novelist, recognized on an international scale, two of whose novels have been turned into films, but Italian novelist Elena Ferrante kept her identity a secret ever since she published her first novel in 1992.

That changed on Oct. 2, when Italian investigative journalist Claudio Gatti claimed to have revealed the person behind Ms. Ferrante, a pseudonym, as Anita Raja, a Rome-based translator born in Naples. The unmasking immediately sparked a firestorm, and overnight, Ferrante fever – the popular author has always fiercely guarded her privacy – turned to international Ferrante furor.

In a piece for the New York Review of Books, Mr. Gatti cited the author as, "Anita Raja, a Rome-based translator whose German-born mother fled the Holocaust and later married a Neapolitan magistrate."

Though not definitive, Gatti's conclusion comes from financial records and real estate transactions that show payments to Raja, listed as a consultant at the publishing house that publishes Ferrante's work, skyrocketing since 2014, when her four Neapolitan novels became an international phenomenon.

Gatti said Ferrante was one of the most well-known Italian figures in the world, and that there was a “legitimate right for readers to know ... as they have made her such a superstar.”

The reaction was swift.

“We just think that this kind of journalism is disgusting,” Sandro Ferri, Ferrante’s publisher and one of the few people who is known to know her identity, told the Guardian. “Searching in the wallet of a writer who has just decided not to be ‘public.'"

“There is something troubling in the whole pursuit, as if male critics see her refusal to reveal herself as an insult. Do we pursue reclusive male writers in the same way? What do you know about Thomas Pynchon’s finances? Or JD Salinger’s address?" British novelist Jojo Moyes wrote in an essay published in the UK's Telegraph.

And Twitter was alight with scathing criticism all week.

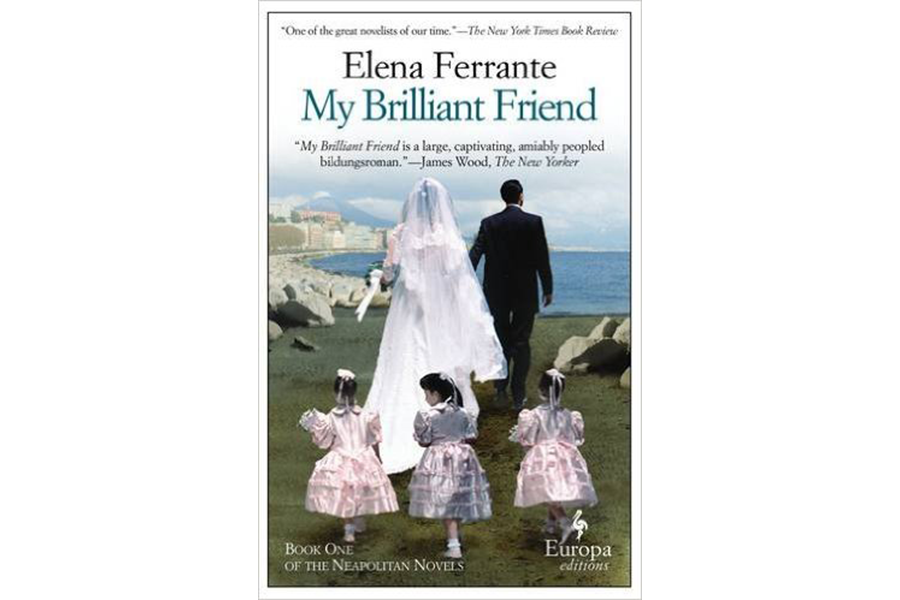

Not all writers shared that position, however. Literary critic Marco Roth said the outing was inevitable. “Conditions change for all writers once they’ve been published and it’s naïve to assume that Ferrante’s pseudonymity (had it been protected) would have allowed her to flower forever in the brilliant vein of ‘My Brilliant Friend,’” Mr. Roth wrote on Facebook, referring to the first of Ms. Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels.

“Anita Raja will now have to work this new twist in her life into the next stage of her work, whatever that may be. No writer can control or really has the right to control the conditions of her reception,” he added.

Roth was in the minority, however, and for many fans, Ferrante's unmasking was a violation.

That's because Ferrante has always zealously guarded her anonymity, insisting it allows her to be brutally honest in her writing. In fact, she has repeatedly insisted that anonymity is a precondition for her work.

“The wish to remove oneself from all forms of social pressure or obligation. Not to feel tied down to what could become one’s public image. To concentrate exclusively and with complete freedom on writing and its strategies,” she wrote in an email interview for the Gentlewoman.

"To relinquish it would be very painful," she once told Vanity Fair.

"Readers – and critics – particularly admire Ferrante for her ability to capture the inner lives of women, a feat that the author has always suggested requires her to be shielded from public scrutiny," writes the Guardian.

And public scrutiny has not been entirely kind to Raja. Some of Ferrante's fans have been disappointed to think that Raja might be Ferrante because (1) the details of Raja's life do not correspond to the autobiographical hints dropped in Ferrante's book "La Frantumaliga," (2) Raja has spent most of her life in Rome and not Naples, and (3) Raja's husband is the novelist Domenico Starnone – sometimes speculated to have been connected to Ferrante's work because of stylistic similarities between the two writers. Some of the purists among Ferrante's fans do not like the idea that there could have been an established male writer influencing Ferrante's novels.

Male power and gender are central themes in Ferrante's works. Some readers have also suggested that the "puncturing of Ferrante's anonymity was an act of masculine aggression."

"Ferrante has talked about 'male power, whether violently or delicately imposed, still bent on subordinating us,' and – while I am sure this was neither the motivation of Gatti or the NYRB – there is the regrettable, sulphurous whiff of a female artist being ‘mansplained’ here," explained the Times Literary Supplement.

While it's not the first literary "outing" – Robert Galbraith was revealed to be J.K. Rowling in 2013, Richard Bachman has been outed as Stephen King, among many others – it draws fresh attention to the importance of privacy for many writers.

"Privacy is essential for writers," novelist Roxana Robinson wrote for The Washington Post. "It may be mental isolation rather than physical – some like to write in coffee shops, some prefer the cork-lined study – but wherever she is, a writer must be able to be alone with her work. This is not just a question of concentration; it can be a question of creation. Being alone with your work is essential to making it."