Finally – giving women artists their due

Loading...

Back when she attended college in the 1980s, Bridget Quinn flipped through her gigantic art history textbook in search of a female artist. And she flipped some more.

Five hundred pages passed before she encountered a woman painter in a section on the early 17th century. "That's a really long time," she says. "Then I started keeping track page by page of all the women. By the time I reached the early '80s, 16 were mentioned."

It could have been worse, and it was. All the previous editions, the professor joked, only included females without their clothes on – nothing but nudes.

"Not really, but you know what I mean," her professor said. "No women artists."

Quinn became an art historian, devoting much of her career to upending myths about women who created art. "There was an assumption that there weren't any women artists, or there weren't any good women artists, or that just somehow congenitally women are just not very good," she says.

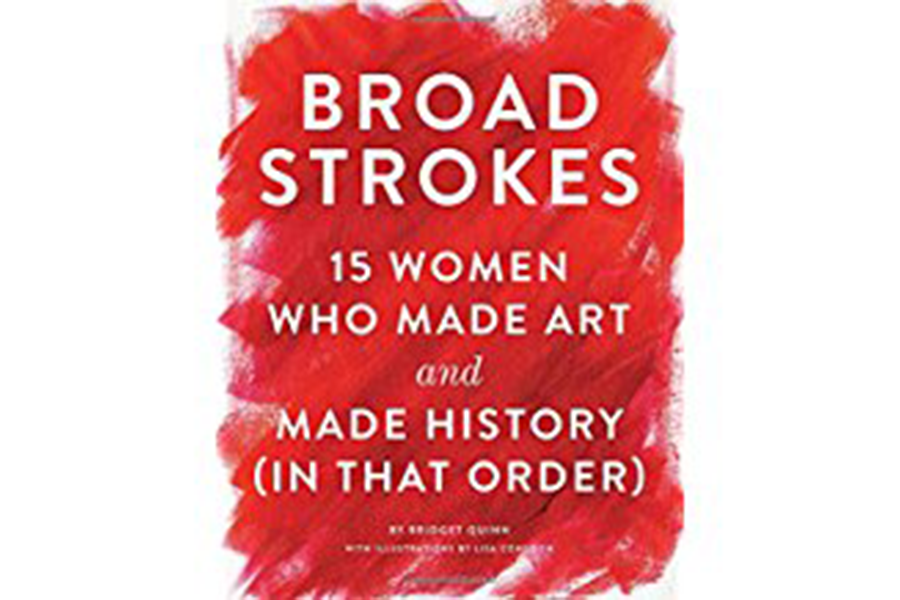

We may think we know better now, but most of us could probably name a handful of female artists at most. Quinn aims to boost that number in her new book Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order).

As its title suggests, "Broad Strokes" isn't stuffy. There's plenty of scholarship here about women artists over the centuries, but Quinn combines her research with a lively, breezy tone that turns her subjects into more than feminist symbols. They're masters in their own right, bold and brilliant despite the limits they faced – getting trained, finding buyers and being taken seriously.

"It's not enough to say, 'There were women artists,'" Quinn explains in an interview with the Monitor. "There were very good artists who were successful in their time and are overlooked and forgotten. They're worth remembering for the quality of their work."

Q: Who's one of your favorite artists in the book?

Edmonia Lewis. Her life is so remarkable that's it's amazing someone like that could be forgotten in America.

Q: You describe Lewis as one of the nation's most important and celebrated sculptors of the 19th century. As you write, her masterpiece went missing for a century, only to be discovered in a storage shed at a shopping mall in Ohio in the late 1980s.

Where did she come from and what did she do?

She's born to an Haitian-American father and a Chippewa mother and raised in upstate New York. She gets a scholarship to Oberlin College where they had a mixed student body – black and white, male and female – and attends during the Civil War.

She's accused of drugging fellow female students with Spanish fly, an aphrodisiac. She's taken out by vigilantes and beaten, defended by one of the first black lawyers in Ohio, and found innocent.

Sponsored by abolitionists, she goes to Boston and begins to study with a male sculptor. She becomes an excellent sculptor, goes to Europe and becomes a renowned artist with a great career, one of several successful woman sculptors in Rome. When Frederick Douglass and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow are traveling abroad, they stop to visit her.

But then she's forgotten to the point where her masterpiece was hidden for years and years.

Q: Earlier this year, Google's home page celebrated Lewis and her recovered masterpiece "Death of Cleopatra" with a "Google Doodle," giving her some newfound fame. (The Monitor published a brief story about her work and influence after Google honored her.)

How has the appreciation of women artists changed over the last few decades?

When I was in grad school 30 years ago and interested in looking at women artists, there was this feeling that to do so was to lower your sights in terms of quality. It seemed very marginal.

Now, gender is not a major component of an assessment or discussion of the art that women are making today. That's great. But if you look at auction records, gallery shows, and museum exhibits, men are responsible for 70 percent of the work. The disparity is still there for sure.

Q: What should we think about the progress that's been made?

I'm realizing how these artists were successful but how nothing came of it in terms of being recognized because things change so much in history.

In the 18th century, for example, women were painters in the French royal court and could not have been more successful. But then the revolution comes and Napoleon makes it impossible for women to study at royal academies.

The past is not a progression toward progress – "This happened, and women got this, and now everything is great." Gains can be lost, rights can be lost, and the ability to create your own life can be lost. History doesn't have to move in one direction.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is immediate past president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.