Oil prices drive Delta Air Lines to buy its own refinery. Will that work?

Loading...

In an age of volatile and sky-high oil prices, Delta Air Lines is trying to cut its costs in a novel way – by purchasing its own refinery.

A Delta subsidiary this week announced plans to buy the Trainer refinery complex near Philadelphia, saying it could reduce the airline's annual fuel bill by $300 million.

That's a sizable chunk of change. Of course, owning the refinery doesn't insulate the airline from the impact of changes in the price of crude oil, which has risen over the past year due to factors ranging from the geopolitics of Iran to signs of reviving demand.

But Delta chief executive Richard Anderson says the move will help the firm control fluctuations that can occur in the so-called "crack spread" – the gap between the price of crude oil and the cost of refined products such as jet fuel.

"What we're tackling here today is the jet crack spread, which you cannot hedge in the marketplace effectively," Mr. Anderson told reporters Monday, according to the Associated Press. He called it Delta's fastest growing cost.

Some energy analysts say it may take a while before it's clear whether Delta's strategy will reap the intended benefits. The refining business can see sharp swings in costs and revenues, and the Trainer refinery complex requires substantial new investment by Delta.

But they also say the company has its eye on an important cost problem.

"There's a real scarcity of jet fuel in the Atlantic basin market," says Andrew Reed, an industry analyst at the consulting firm Energy Security Analysis in Wakefield, Mass. He says Delta may have found a solid strategic move – "if it works out." The airline is "moving from one difficult sector into another."

If successful, the step could become a model for other airlines.

Although the facility will now focus on boosting jet fuel output, that won't be a bad thing for car drivers in the region. ConocoPhillips had already shut down the facility, and it might never have reopened without the Delta deal. Now the facility will continue to make a variety of oil-based products including gasoline.

"It's just that much less gasoline that we're going to need to import," Mr. Reed says.

The future of two other East Coast refineries, including a larger one owned by Sunoco, is also in doubt. They have come under financial pressure because of weakened demand and imports from places like Europe. Reed says he will be surprised if both survive.

Delta's Monroe Energy subsidiary will pay $150 for Trainer, plus make a $100 million investment to convert the facility to maximize its jet-fuel output.

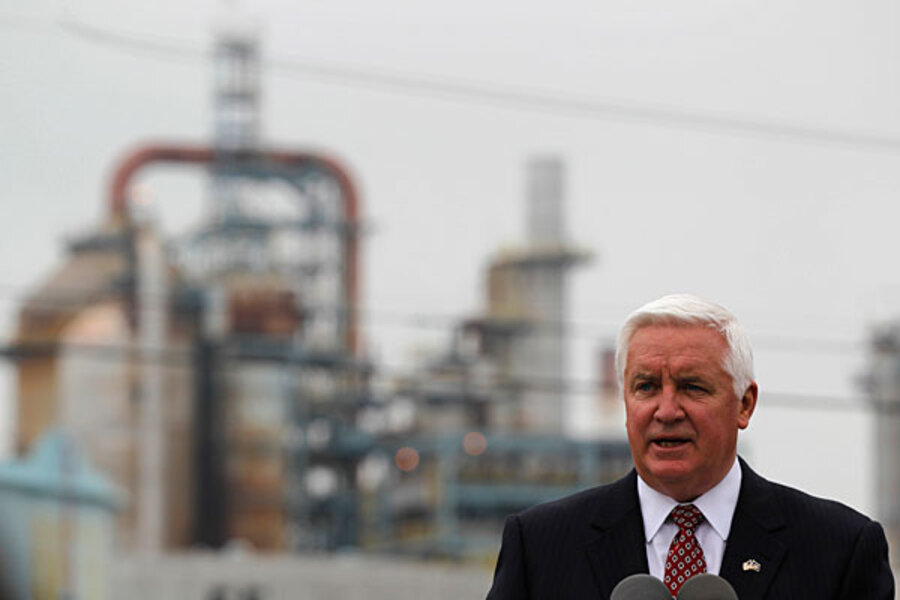

Preserving the Trainer refinery means more than 5,000 jobs there and in related industries, Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Corbett said in a statement. Because those jobs were at stake, the state is kicking in $30 million to help the deal happen.

The jet fuel will flow by pipeline to the region's major airports, including those in New York City, where many Delta planes fill up.

Delta's Monroe unit will enter multiyear partnerships with BP and Phillips 66 to buy the needed crude oil and to exchange the refinery's nonairline products for jet fuel elsewhere in the country. Delta said it hopes the refinery deal will thus meet 80 percent of its US fuel demand.

The Trainer facility can refine 185,000 barrels per day, Delta said.

Fuel has become the largest and most volatile expense for most airlines. Delta planes burned 3.9 billion gallons of fuel last year, about 36 percent of the firm's operating expenses, according to the Associated Press. Against that huge $11.8 billion cost, the savings from the refinery deal appear to be modest.

But in the highly competitive airline business, something like the hoped-for "crack spread" edge can be important.