Rust Belt revival: a bounce back for rubber?

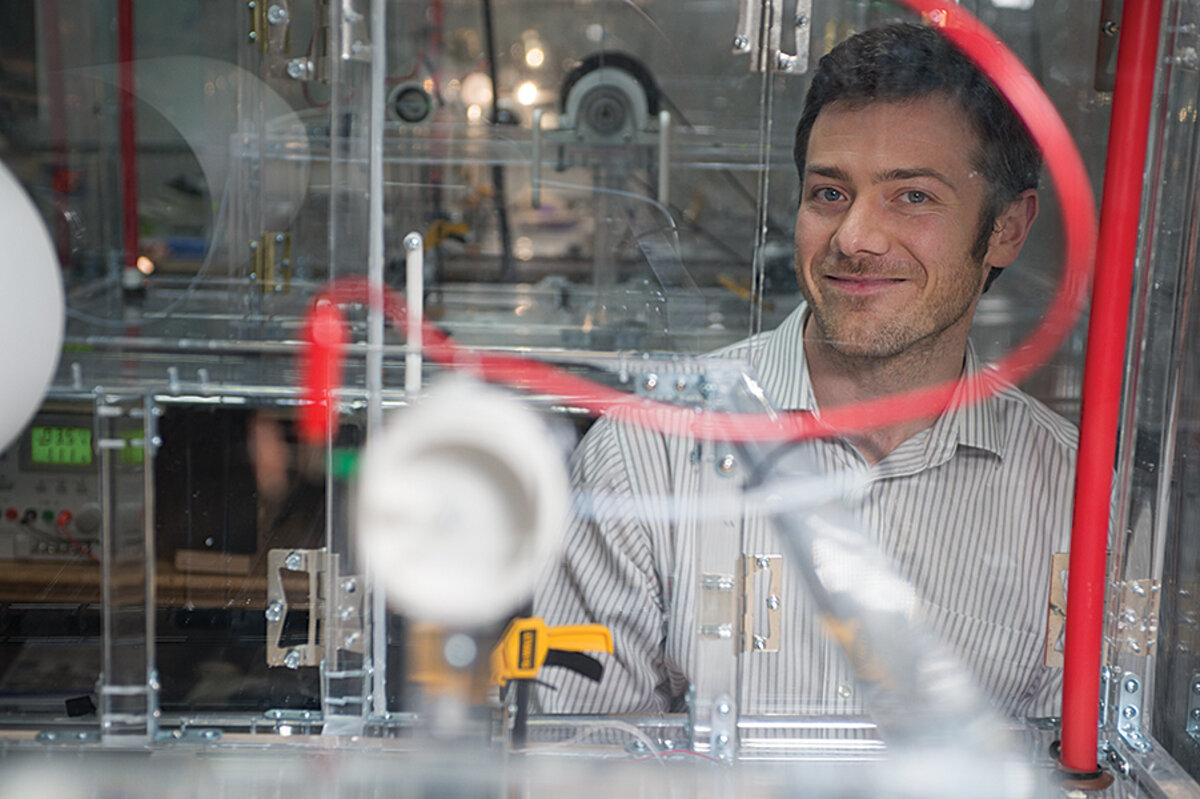

Inside a clear plastic box the size of a rabbit hutch, a 12-inch drum turns slowly on its axis. At each turn the drum is coated with polymer threads, 100 times as thin as a human hair, fired from a needle-and-syringe electrospinner, just as Spider-Man shoots his webs. It takes 20 minutes to produce an adhesive film.

What exactly that film – which mimics the feet of the wall-scaling gecko – could do, and in which industries, is still being determined. But the promise of a dry adhesive – a binding material that uses no glue and can be applied and removed as needed, like invisible thumbtacks – has sparked commercial interest in Akron Ascent Innovations (AAI), the start-up that runs this lab in a refurbished red-brick tire factory.

It’s a “universal magnet,” says Kevin White, the start-up’s chief operating officer, who has Spider-Man posters on his walls, sticking without pushpins or tape.

It’s the kind of innovation on which Akron, Ohio, wants to build its economy, one less dependent on the ups and downs of labor-intensive manufacturing that can be outsourced or automated. That it involves polymers is no coincidence. A century ago, this was “Rubber City,” the hub of tire production that supplied Detroit’s assembly lines. When US tire manufacturers moved out in the 1970s and ’80s, decimating the economy and depleting its population, much of the expertise remained.

Today Akron sits in a region that boasts a major plastics industry. But like many other Rust Belt cities, Akron has a workforce that’s increasingly involved in services such as health care, retail, and education; manufacturing continues to decline, with thousands of jobs shed since the Great Recession.

Few expect those factory jobs to return under President Trump. What they hope is that Akron can become a center of advanced manufacturing, where the United States has a comparative advantage and which rewards pioneers of new materials and applications fresh out of the lab.

With a research university, industrial infrastructure, and public-private partnerships, Akron is among several US cities poised to lead a revival in US manufacturing, says Antoine van Agtmael, an economist and coauthor of “The Smartest Places on Earth: Why Rustbelts Are the Emerging Hotspots of Global Innovation.” His book names Akron; Albany, N.Y.; and Minneapolis as examples of “Brain Belt” cities on the rise.

He argues that the outsourcing of factory work to China, Mexico, and other emerging markets – a term he coined in 1981 – may have run its course. A new era of 3-D printing, smart devices, big data, and automation makes the US and Europe more attractive as places to develop and build new products that can be quickly brought to market.

“We are regaining our competitiveness in manufacturing irrespective of who is the US president. It’s a trend,” says Mr. van Agtmael, who runs a consultancy in Washington.

Akron has survived the death of old-fashioned manufacturing. Now it wants to hitch its fortunes to the industries of the future. “Akron is a city that has always reinvented itself,” says Sam DeShazior, the deputy mayor who oversees economic development.

Mr. DeShazior grew up on his family’s farm in Georgia. In 1919, his great-uncle Herbert was a demobilized soldier at a train station in New York, headed back to the farm after fighting in Europe, when his life took a turn.

“Firestone was there trying to get labor to come out here. Herb took [the recruiter] up on it [and] said, ‘So where’s Akron again?’ He comes here and makes more money than he ever made in his life,” says DeShazior.

Firestone later sent Herbert back to Georgia to recruit more African-Americans like himself to move north. He drove a new Ford and wore fine clothes, a walking advertisement for the weekly wages that awaited economic migrants to Akron in the 1920s.

Today DeShazior is selling a different story about Akron, one rooted in its strengths in high-tech plastics and metalwork, software start-ups, and hospitals. He pitches foreign companies looking to plant a flag in the US and drums up state funds and private capital for economic projects.

He knows that an upswing in US manufacturing won’t mean a return to the payrolls of the past. Since 2009, the recession’s nadir, manufacturing output has grown by 20 percent, but employment has risen only 5 percent. Advanced industries tend to employ fewer people in smaller facilities and prioritize education and computer skills in hiring technical staff. But the jobs they create often pay well and are less dirty and dangerous than the ones in the factories of yesteryear.

Akron has yet to see the full gains from its economic restructuring. Its average household makes less than $35,000 a year, heroin overdoses are soaring, and the city is short of funds. Only an influx of refugees is keeping its aging population of 200,000 from shrinking further.

But developers are building downtown and tapping demand for Millennials to live and work and bike in the city, breathing life into distressed districts.

For its leadership, there’s no turning back. “We’ve been innovative for 150 years. We’re not going to stop now,” says Dan Horrigan, the city’s mayor.

A start in fire hoses

When Benjamin Franklin Goodrich founded a rubber company in Akron in 1870, his main product was fire hoses. In the 1890s, that changed to pneumatic tires for bicycles – followed by tires for automakers that by 1913 were going on more than a million cars a year. Akron became the world’s rubber capital, a title it held for much of the 20th century. (Today, it’s perhaps most famous as the hometown of National Basketball Association star LeBron James.)

The big rubber companies – including Good-rich, Goodyear, and Firestone – built vast factory complexes and housing estates for workers and their families. By 1960, the city had grown to 290,000 residents. Unionized employees working six-hour shifts earned enough to buy vacation homes and boats.

The good times didn’t last. Tiremakers that had been nimble and inventive – working together to develop synthetic rubber in 1942 after Japan stopped natural-rubber supplies from Asia – grew complacent.

In the 1970s, France’s Michelin rolled out the radial tire, a breakthrough that would become the new standard. US tiremakers just “pooh-poohed it. They said, ‘It’s a fad that will go away,’ ” says David Lieberth, a former city official and local historian.

Instead, the industry itself went away. Akron made its last passenger tire in 1982. That same year, a politician first used the phrase “Rust Belt” in a speech. “Akron, because it was so closely tied to a single industry ... was feeling a sudden and profound loss of identity. The term Rust Belt was sucked hard into that void and there it would stay,” wrote David Giffels, an author and journalist, in a 2014 collection of essays.

People left in droves. In the 1980s, says Professor Giffels, who teaches English at the University of Akron, the city was so empty that you could drive downtown on a snowy night and follow your own tire tracks home.

Akron desperately needed a new economic model. But what would it be?

The answer lay in the industry on which the city built its fortunes. Tire companies that had shut their factories kept on many of their engineers and executives. “We lost the blue-collar jobs. But the highly paid white-collar people stayed,” says Mr. Lieberth.

Companies that had supplied tiremakers began developing synthetic materials and products for Ohio’s plastics industry. The health care and transportation industries also started to grow. But the transition was slow, and city officials had to beg for state and federal funds to rebuild the scarred downtown, where squatters took refuge in empty office buildings.

Piles of tires

DeShazior, the deputy mayor, moved to Akron in 1986, when reinvention was more talk than action. At the time, he recalls, piles of scrap tires stood in abandoned factory yards. He knew of the Rubber City’s glory years from family lore about his great-uncle Herbert, the recruiter who drove south to find laborers.

After earning a master’s in urban planning and economics, DeShazior joined the regional development board and had a hand in the revitalization of the city’s manufacturing base, including companies founded by former tire-industry employees who came out of early retirement to go it alone.

“People began to say, ‘There are things I always wanted to do but I never did because I had such security in my job. Now I’m going to try that,’ ” he says. Had the tire industry not collapsed, this entrepreneurship may never have happened. “There’s such a safety blanket that you don’t have to think outside the box.”

‘Polymer Valley’

In 1999, the University of Akron appointed Luis Proenza as its president. He would lead an ambitious $650 million, debt-funded expansion program that would transform the campus and the city, raising Akron’s profile and orienting its academics toward commercial discoveries.

At the time, the university enrolled about 18,000 students. Under Mr. Proenza, the campus grew in size and added 22 new buildings and 34 acres of green space. Other buildings were renovated to create a campus that is integrated with the city and its housing stock.

By 2011, enrollment had swelled to 30,000. Downtown Akron was no longer a ghost town: A new convention center, baseball stadium, and museum also brought in visitors and revenue.

Proenza’s vision went beyond a vibrant campus. He wanted the university to become an engine of regional economic development, a place where industry and government could find and support research that would lead to marketable products and services. Polymer science, in his view, was the perfect place to start looking.

“What was unique about Akron was this strong underpinning of academic and research capacity to make this expansion from rubber,” says Proenza.

Much of this research takes place in the Goodyear Polymer Center, a 146,000-square-foot glass and steel tower that is the tallest on campus. Built in 1991, it houses the College of Polymer Science and Polymer Engineering, top-ranked in the country, with hundreds of graduate students from around the world.

This is where AAI began, in the lab of a professor who was experimenting with polymer nanothreads. Matthew Becker, associate dean for research, joined the faculty in 2009. He has since founded two start-ups to develop biodegradable materials for reconstructive surgery, including one bone-repair material that will be part of a trial conducted by the US military this year.

His research is supported by federal grants and private companies, and he trains graduate students from seven countries. “I’m in the right ecosystem here,” he says.

Most research and development in the US is done by companies. But the private sector has long relied on scientific research at public institutions – such as government labs, universities, and military facilities – to unearth new technologies, from the internet to microchips to GPS.

After 2008, many US corporations cut their R&D budgets, says Barry Rosenbaum, a chemical engineer who spent 25 years working at Exxon. That left a void that needed to be filled.

“Industries were cutting back, and funding agencies for universities were encouraging universities to focus more of their attention on bringing their research to industry,” he says.

Proenza recruited Mr. Rosenbaum and other retired executives as unpaid advisers to the University of Akron Research Foundation (UARF), a nonprofit he set up in 2001. The aim was to link more closely the ideas hatched on campus with the needs of industry, and to promote entrepreneurship by faculty and students so that start-ups like AAI could emerge from research labs. (Rosenbaum is chief executive officer of AAI.)

“It’s not about doing research and throwing it over the wall. It’s about changing the way we do research projects,” says Eric Amis, dean of the polymer college.

Instead of waiting for companies to read academic papers on new discoveries, UARF promotes the university’s breakthroughs and finds companies to partner on projects. Akron also works with nearby Kent State University and Case Western Reserve University, with Northeast Ohio now sometimes referred to as “Polymer Valley.”

“If we can apply the inherent expertise that universities have to solve our industrial and community problems, it creates economic development and jobs for our students and value for our university,” says Rosenbaum.

Some start-ups move downtown into the Akron Global Business Accelerator, the old tire factory where AAI spins its webs. Since 2010, tech-heavy companies based there, including foreign-invested start-ups, have created a combined 791 jobs and have secured $165 million in investment, according to its chief executive officer, Anthony Margida. GOJO Industries, the maker of Purell hand sanitizer, is across the street: It employs about 600 people in a former Goodrich building.

Handcrafted tires

Even the tire business is expanding again, though not in mass manufacturing. Bridgestone opened a $100 million research center in Akron in 2012, and other tiremakers have added research labs in Northeast Ohio.

Goodyear rebuilt its corporate headquarters in an airy seven-story complex with an innovation center grafted onto its old red-brick plant, where it still makes highly engineered tires for race cars.

Every year Goodyear produces more than 100,000 tires for NASCAR teams, all made by hand. It’s a labor-intensive process, more artisanal than industrial, with a $2,000 price tag for a set of tires that will be raced only once. Nearly 300 workers assemble the tires on three floors of the 845,000-square-foot building.

On a recent afternoon, a Goodyear technician lays black composite strips on a turning spindle, building a NASCAR tire. Each strip was cut to specifications and monitored by sensor chips, yet the careful layering is that of a pastry chef preparing a mille-feuille slice.

Once the technician is satisfied, the tire is inflated and sent downstairs to be cured, finished, and sent to the racetrack.

Speed bumps

Proenza stepped down as the University of Akron’s president in 2014. By then, funding for research projects had grown dramatically and dozens of start-ups were mining the results. But the breakneck expansion also hit speed bumps: Enrollment was down to 26,000, a $62 million football stadium hadn’t attracted the promised crowds, and a much-hyped bioinnovation center flopped.

With its current enrollment of 23,000, the university faces a $30 million deficit this year. It pays about $38 million a year in interest on the bonds issued for the campus expansion program, says Dan Minnich, a spokesman for the university.

Proenza defends the buildup of debt and putting the stadium on campus. Still, he concedes that the timing was bad.

The Austen BioInnovation Institute, a joint venture between the university and local hospitals, got shortchanged by funders, including the state government, says Proenza.

A broader criticism of the approach is that it tilts publicly funded education toward a form of corporate welfare in which faculty and students become adjuncts to private capital.

On some campuses, the sponsorship of labs blurs the lines between academic and corporate research, says Douglas Oplinger, newly retired managing editor of the Akron Beacon Journal. “Ohio has turned universities into research facilities for industry where students who pay tuition are doing the work,” he says.

And yet Goodyear, unlike its competitors, never left Akron. “One of the reasons we decided to stay here was the University of Akron and their researchers,” says David Zanzig, director of global materials science.

In 2014, when the company announced plans to build a factory employing about 1,000 people to produce premium tires, Akron vied publicly with South Carolina’s Chester County to be its location. Goodyear chose neither. Instead, it is building a factory in Mexico.

Had Goodyear added a new plant in the US, it would have been an outlier: Factories of such size, while dominant in the public imagination, are no longer the norm. Only 15 percent of manufacturing workers, or just over 1 percent of the US labor force, punch clocks in factories with 1,000 or more employees. The majority of factories have fewer than 100 workers.

Start-ups like AAI, which has five full-time employees, hold out the promise of rapid growth that rewards investors and encourages more entrepreneurship. It fits Akron’s self-image as a bootstrap city of inventors taking what writer Giffels calls “the hard way on purpose.” But it may never match the employment levels and job security of the old assembly lines.

“If you define manufacturing as you need someone to pull a lever, those days are gone,” says Mr. Becker of the University of Akron.

‘What happened to Uncle Herb?’

After DeShazior moved to Akron, he grew curious about his great-uncle’s past in the glory days of tiremaking. “I’ve heard the stories from parents and grandparents. I said, ‘What happened to Uncle Herb?’ ”

Eventually he tracked down his great-uncle’s medical records and found that he had been diagnosed before his death with lung cancer, probably from the carbon black used to make tires. “That was so common, so common,” he says.

It’s a story he sometimes tells when people in Akron wax nostalgic for the tire-industry jobs that were lost here, glossing over the acrid smoke that shrouded the city’s east side and the health risks inside the factories that ran day and night.

“If you want that particular environment to come back, I don’t know you’d be able to get that back,” he says.