- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for October 30, 2017

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Last week, we wrote about how, amid the chaos of a redone election in Kenya, a silver lining was the growing assertiveness of an independent judiciary. Kenya might seem a long way from Washington, but today was a reminder of how crucial that underlying ideal remains.

President Trump’s former campaign manager, Paul Manafort, was indicted on charges of money laundering and conspiracy Monday. The charges do not appear to point to Mr. Trump, though a guilty plea by another former Trump official, George Papadopoulos, is significant. He admitted to lying to the Federal Bureau of Investigation and is working with investigators.

That investigation could soon become enormously divisive. Many of the loudest voices in politics are not inclined to trust the motives of those seemingly aligned against them. But, as the Founders realized, law is law. It is where politics must ultimately yield. It is perhaps the one place where facts can outweigh spin, “fake news,” and polarization, and establish some shared rules for society.

Kenya, it seems, is seeing glimmers of the power of that idea. For the United States, the nation itself is a testament to it.

Click here for a piece by Laurent Belsie and Mark Trumbull on how federal officials’ best weapon in targeting corruption is to follow the money.

And here are five stories for today, highlighting identity, responsibility, and one of the unlikeliest models for energy conservation you could imagine.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Amid federal tax reform tiff, one state’s saga of cuts and spending

Since President George H.W. Bush broke his promise – "no new taxes" – and was voted out, many conservative lawmakers have rejected the idea of tax increases out of hand. But there are signs that that mind-set might be changing.

The Republican penchant for tax cuts is being tested at the state level. Oklahoma gave generous tax breaks for businesses and high earners, and now is struggling to pay for basic public services. Deep cuts in education funding have led dozens of districts to adopt four-day school weeks to save money. Health-care services are also under strain. So conservatives and business leaders in this state are rethinking priorities, as has also occurred in nearby Kansas. Oklahoma’s largely Republican Legislature voted last week on one measure to fill the gap. But it failed to win the needed three-fourths supermajority, with the Legislature's Democratic minority calling for the state to collect more from oil companies. Even some oil producers agree the industry should start paying more. “We can’t cut our state government to the bone and expect our state to do well,” says Dewey Bartlett Jr., past president of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association.

Amid federal tax reform tiff, one state’s saga of cuts and spending

As past president of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association, an industry body that his father helped to create, Dewey Bartlett Jr. is a familiar voice in policy debates.

So when he began calling this year for higher state taxes on oil producers to help fund cash-strapped public services, Oklahomans sat up and listened. “I came out of the closet,” jokes Mr. Bartlett, a two-time Republican mayor of this city, once called the Oil Capital of the World.

Many of Bartlett’s oil-industry peers didn’t like what they heard. Soon Bartlett was facing calls to stick to the group’s talking points – keep taxes low to encourage oil exploration – or resign from its board of directors. So far he’s done neither, insisting that he has a right to speak out.

Now, as Oklahoma stumbles through a budget crisis after years of steep tax cuts, his call for higher taxes on his own industry and a rethink of what makes a state’s economy viable has struck a chord here.

On Wednesday, the Republican-dominated legislature failed to muster the supermajority needed to pass an interim bill to fund essential health services, deepening a political impasse. But many Republican legislators agree with Bartlett that what's needed is to put Oklahoma’s finances in order so that it can afford to pay teachers more and invest in social programs and infrastructure.

“We can’t cut our state government to the bone and expect our state to do well,” Bartlett says.

Echoes of Kansas

As in Kansas, where tax cuts in 2012 led not to supersized economic growth but to a fiscal cliff, Oklahoma may serve as a cautionary tale in the national debate over the efficacy of cutting personal and business taxes in order to spur spending and investment.

Like Kansas’s Republican governor, Sam Brownback, Oklahoma’s Mary Fallin was elected in 2010’s “Tea Party” wave election that gave her Republican party a free hand at fiscal experimentation. Governor Fallin vowed to eliminate state income taxes and make Oklahoma more attractive to business, in part by shrinking the state government.

Fallin’s tax cuts were less drastic than those in Kansas, which saw an immediate drop in revenues. But the global crash in oil prices in 2014 laid bare Oklahoma’s fiscal vulnerabilities. Yet the state failed to roll back generous tax breaks for oil and gas producers and other powerful industries, even as budget deficits piled up, year by year.

Mike Mazzei, a former state senator, says oil and gas is a vital industry in Oklahoma, but argues that lawmakers “went overboard” in granting special incentives. They “went way beyond what we could afford if we wanted to maintain some prudent financial management,” says Mr. Mazzei, a Republican, who left the Senate last year due to term limits.

A recent stress test by Moody’s Analytics of states’ ability to weather another recession ranked Oklahoma 48 out of 50 states based on the gap between its actual reserves and what it would need. The report found that 14 other states were similarly unprepared, and only 16 states currently had enough in reserves to withstand a moderate recession.

‘Communities are feeling it’

In the past few years, as Oklahoma’s state agencies, from prisons to schools to hospitals, struggled to cope with steep budget cuts, Fallin has recanted. The governor has urged a Republican-dominated legislature to mobilize the three-fourths majority required to raise taxes and restore funding. Deep cuts in K-12 spending have led dozens of districts to adopt four-day school weeks to save money.

“We’re seeing Republicans who recognize they can’t cut any further, that they cut taxes too much and that we need revenues,” says David Blatt, who runs the Oklahoma Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank in Tulsa. “Tax cuts have consequences.”

Mr. Blatt, a former fiscal expert in the state Senate, says “Oklahoma has always been a low-tax state that underfunds public services…. Communities are feeling it.”

In May, lawmakers narrowly passed a $6.8 billion budget that, as in previous budgets, relied heavily on nonrecurring sources to close a $748 million deficit. Three months later, the state Supreme Court ruled a cigarette tax designed to fund health services unconstitutional, forcing a special session to convene since last month.

The bill unveiled Monday by Republicans would have raised taxes on cigarettes, fuel, and beer to make up the shortfall. It also set aside money for higher salaries for teachers and other public officials amid widespread concerns about staff recruitment and retention. But the bill spared tax breaks for oil producers, to the frustration of Democrats and some Republicans.

Should lawmakers fail to plug the gap, health officials have said they would slash staff and programs, including virtually all outpatient services for mental health. A spokesman for Oklahoma’s Association of Chiefs of Police said on Wednesday that the criminal justice system couldn’t cope with any further cuts.

“If we don't act immediately, we will be killing Oklahomans on a daily basis because we are not providing them the necessary mental health treatment,” Brandon Clabes, a police chief, told a press conference in Oklahoma City.

Effects on growth?

Unlike the federal government, most states have to balance their budgets, which makes them an inexact analog for federal tax policy. A 2015 study by the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center found little evidence that state tax cuts had a positive or negative effect on economic growth, contrary to the claims of free-market think tanks influential in Republican circles.

Defenders of Kansas and other tax-cutting states argue that lawmakers gave up too quickly on their fiscal experiments. In June, moderate Republicans and Democrats in Kansas voted to raise taxes, overturning Governor Brownback’s veto. Still, Kris Kobach, a Brownback ally who is vying to replace him when his term ends next year, stood firm. “Kansas does not have a revenue problem. Kansas has a spending problem,” he said.

In Oklahoma, Mazzei says similar arguments are losing steam because many voters are seeing the results of government cutbacks, particularly at local schools. “Your typical Republican in this state now understands we’re behind the curve, and we can’t fix the problem with more cuts,” he says.

A debate over oil incentives

Bartlett, on the board of the oil industry trade group, opposes one particular tax break: a 2 percent rate on oil production from new horizontal wells, which are drilled into shale beds, typically by larger companies. The tax break was first introduced in 1994 to incentivize what was then a new and risky technique. Traditional vertical wells, which Bartlett’s family firm operates, are subject to a 7 percent tax.

Today the majority of wells in Oklahoma are horizontal, and Bartlett says the tax break is no longer needed. “In my view, we should say hurrah, it was a success,” he says.

Tim Wigley, the trade group’s president, says he sympathizes with legislators trying to balance their budget and points to other oil-related tax breaks that have already been phased out. “We’re in this situation not because the oil and gas industry doesn’t pay enough tax,” he says.

He argues that the 2 percent rate, which covers the first three years of output, is paying off because more companies are drilling in Oklahoma rather than in rival states like North Dakota and Texas, and that means more jobs and tax revenues. “We’ve become the No. 1 target of outside investment in oil and gas,” he says.

Bartlett is still on the board of the industry group, and there has been no formal attempt to remove him, says Mr. Wigley. “He has a difference of opinion with the vast majority of our board members,” he says.

“They’re not quite as friendly to me as they used to be, which is too bad,” says Bartlett.

Share this article

Link copied.

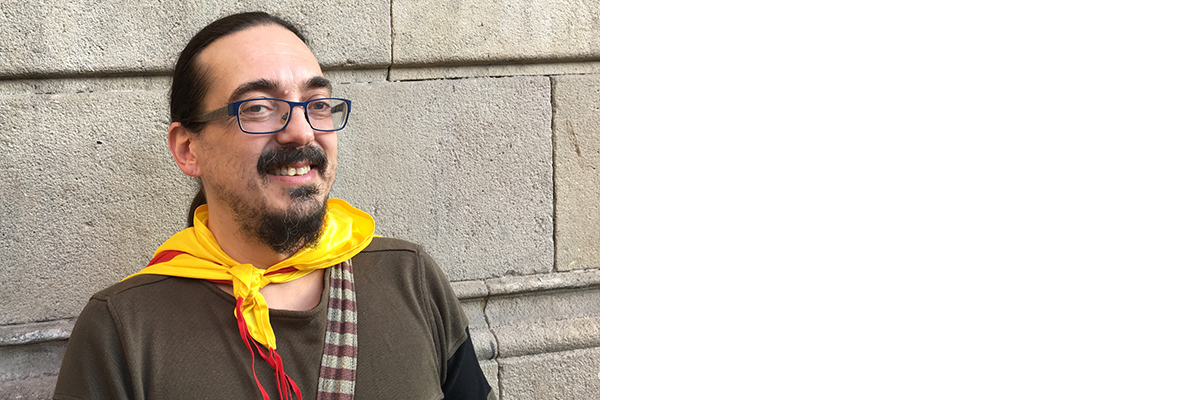

What makes a ‘nation’? Amid Catalonia furor, Spaniards speak.

It can be easy to forget, but Spain is still relatively new to this democracy thing. The tension over Catalonia, many Spaniards say, shows that the country is still trying to forge a sense of identity and unity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Monday morning in Catalonia had echoes of normalcy as officials headed to work and reported to their offices. But it was hardly business as usual: In an extraordinary moment for Spain, the region, formerly autonomous, is now under Madrid’s direct control. Many Spaniards are breathlessly following the play-by-play as Catalonia's politicians spar with Madrid’s. The Monitor asked a variety of people what most concerned them. What surfaced were the difficult issues they are wrestling with – about what their country stands for, about its troubled recent past, and what an independent Catalonia might mean. Some, like Pau Valvas, a high-schooler in Barcelona, says that in his heart, he does not feel Spanish. Carmen Perez counters that she is a Catalan who also feels Spanish. Others are defusing tensions with humor. And still others harbor deep misgivings that their country – which transitioned to democracy only after the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975 – is slipping backward.

What makes a ‘nation’? Amid Catalonia furor, Spaniards speak.

The jokes arrived on cue: As a high-speed train from Barcelona, the capital of Spain's Catalonia region, crossed into the autonomous region of Aragon just hours after Catalonia declared independence, one woman quipped: “We have just left a foreign country.” Behind her, another piped up: “But I don't have my passport.”

Behind the nervous laughter, however, lies a great sense of uncertainty across Spain, including Catalonia, after regional authorities voted to break free Oct. 27 and the central government in Madrid quickly voted to impose order.

It is an extraordinary moment here. Spaniards are jumping on every news alert as the first workweek with Catalonia under Madrid's control begins. Yet beyond the play-by-play, Spaniards are pondering tougher questions about what binds a nation, about what Spain is, and what a nation called Catalonia might mean.

Nicolas Liendo, a chef from Argentina and 19-year resident of Barcelona, says he hasn't taken Spanish nationality because he is waiting for a Catalan passport. To him the creation of Catalonia is aspirational.

A nation is something that is the exact opposite of Spain. Spain is a kingdom. The US is a nation. … A resident of Washington does not feel like a Texan, and the Texan doesn't feel Californian, but all feel American. No one is questioned if they feel different. That is a nation, when all the voices feel represented, not when voices feel silenced. … We are in favor of a country without corruption, without authoritarianism, without the repression we experienced Oct.1 (when the Catalan independence referendum was held). We want a country that is more equal, fairer. We want a country that doesn't benefit the economic hierarchies, that is a country of the people. … It is a demand for a different kind of democracy.

For Pau Valvas, a high school student waiting outside the Generalitat (the seat of Catalonia's regional government) in Barcelona to see if independence were declared, a new nation is a clear protest against Madrid.

A nation is a group of people who think the same, want the same, who support one another. In my heart I do not feel Spanish, even though I have been part of this country for many years. But you get tired of all the corruption in the central government. You don't like it. As a young person, I feel our future is at risk. We invest money in Spain, and they spend it, and we do not get the money back, to invest in education, to invest in our future.

Yet many other Catalans, like Carmen Perez, says she has a dual identity, and a new Catalan nation robs her of that.

I am Catalan. But I also feel Spanish. I want to live in Catalonia, a Catalonia integrated in Spain and above all in Europe. I think Catalonia is different than Spain, but in Spain the regions are all very different. ... I think Spain has the fortune to have many personalities. But I think Madrid is very centralized and doesn't give us what we need. There was a plan to make Spain federal, like Germany. And this is very important. Oh that Spain were federalist! I believe the Generalitat has some people inside it that are not thinking about Catalonia globally, but in only what they want. They are taking us to ruins. Better put, they have already brought us to ruins. Because 1,500 companies have already gone (since the referendum), the most important companies here, and they are not going to come back. There will be less work here. This is a very tough moment for Catalonia.

Manuel Lopez put a photo of a slice of Iberico ham turned sidways on his Facebook page to represent the Spanish flag (red of the ham and yellow stripes of fat) “because we all love ham,” he says. Despite his sense of humor, he says the independence drive risks taking Spain backward.

If Catalonia becomes an independent country, then it would be the Basque Country, then Galicia ... next. And then we would return to the Kingdom of the Taifas, and then the Moors would have to come back and conquer us, and then we would have to reconquer again. Who has an interest in going down that path again? A nation is a territory, with inhabitants who are more or less homogeneous, with one set of laws for all, a language and a history. It is hard to explain. I have lived in Barcelona for 31 or 32 years. ... I don't ever put Catalan TV channels in my house. Once in a while I will put on a soccer match but with the volume turned off. I decided not to learn Catalan when we moved here and my son, who didn't know a word of Catalan, was forced to speak it exclusively at school.

David Ubico, who was at a protest in Zaragoza the night after Catalonia declared independence to support the region's right to decide, worries about Spain going backward, too, but because of Madrid's takeover.

Catalonia has a very old culture. … The concept of nation in Spain is not clear. Because it is very much determined by the fascist coup of 1936 (that triggered the Spanish civil war). And this history has weighed on the notions of nationality, especially for the left. It has been difficult for the left to identify with the nation when the nation comes from a fascist coup. ... I was born in 1951. In 1975 and 1976, I was in jail. There were a lot of workers' movements on the streets, there were constant strikes, it was the fall of the dictatorship. There was a lot of tension. I was just one of many arrested. My identity is internationalist. At the same time that I am from Aragon, I identify with any community that feels it has the right to decide its own fate.

Olga Moreno, an art teacher in Zaragoza who started an organization to regenerate politics, says that all Spaniards should have a say in whether Catalonia decides to become independent.

Today the Spanish Constitution doesn't contemplate the separation of territories. If there was a referendum it would have to be set up so that all of us can express our opinions. They think this is their problem, they don't realize that others are there, too. Above all we in this region (Aragon) with a physical border. I think we would deserve to have a say, too, to make sure we are in agreement with this.

Yet as Spain remains unsettled by this kind of polarization, the vast majority just care about their own lives. That's the case with Cesar Valencia, a car mechanic in Zaragoza who is originally from Ecuador but has Spanish nationality.

To me a nation is Spain. This crisis with Catalonia, I don't like it. Catalans and Spaniards are equal. Catalonia is Spain. It just a few hours from Madrid, and Madrid is the capital of Spain. … But it is not something that I care deeply about, as long as I have work. This could hurt the economy. Or maybe not. What I care about in life is to be able to progress, to have work, and to move ahead.

Nerea Fernandez, a resident of Zaragoza, says she has faith that Spain's democracy will prevail.

For me Catalonia continues to be Spain. But if Catalonia decides to leave Spain, Spain would continue being Spain, just without Catalonia. I am Aragonesa, from Spain. But my father is from the Basque Country, and I also feel Basque. Spain is very diverse. We are distinct in every region, but this is what is nice. In some places it gets very cold, in others it rains a lot, in others it is hot, people are different, some are harder workers, others are more happy-go-lucky. This is what is nice, this diversity. I do believe Catalans have a right to decide. But it should be done right. … I am worried about the future, but not too much. In the end I think it will resolve itself. I think at the end the two sides will find a way to talk to one another.

Facing deportation, ‘Dreamers’ weigh risk of speaking out

For many young unauthorized immigrants, now is the time to lie low. Yet for others, this is the time their voices are needed most. They want Congress to hear.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

When President Trump ended the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program in September and gave Congress six months to find a legislative alternative, the announcement left Stefanny Amorim and other DACA recipients to grapple with an old question for unauthorized students here – whether to engage in public activism and the risks that could come with it – in a new political climate. Some, like Ms. Amorim, a sophomore at Eastern Connecticut State University in Willimantic, have been inspired to share their stories for the first time, viewing their voices as the most powerful tool for advocacy. Others have pointed to perceived additional risks and growing hostility toward immigrants who are here illegally as reason to back out of the public eye. “We have had a lot more people much more willing to share their story because they sense the urgency of the moment,” says Camila Bortolleto, founder and campaign manager for the statewide advocacy organization Connecticut Students for a Dream. Amorim, whose family moved to the United States from Brazil when she was 5 years old, is one of those. “I feel like it’s really important to have my story out there so people can somewhat understand and sympathize with our cause,” she explains.

Facing deportation, ‘Dreamers’ weigh risk of speaking out

Stefanny Amorim almost didn't appear in this article.

When Ms. Amorim, a sophomore at Eastern Connecticut State University, first opened the email from an advisor asking for undocumented students to speak to a reporter about Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), she hesitated to volunteer. She’d avoided publicly exposing herself as undocumented in the past, cautioned by her mother and deterred by the arrest of a friend.

But in the current political moment, with the fate of DACA up in the air, she felt compelled to speak out.

“We have this time where Congress can really do something about DACA and hopefully, maybe, change something for the better,” explains Amorim, whose family moved to the United States from Brazil when she was 5 years old. “I feel like it’s really important to have my story out there so people can somewhat understand and sympathize with our cause.”

Throughout his campaign, President Trump repeatedly signaled that he would not revoke DACA, which granted temporary protection to some 800,000 undocumented young people who were brought to the US as children and allowed them to apply for work permits. On Sept. 5, in a reversal of that position, the president announced that he was rescinding the Obama-era policy – pending a six-month delay – giving those whose DACA status was set to expire before March one month to submit an application for renewal.

The announcement left Amorim and other DACA recipients to grapple with an old question for undocumented students – whether to engage in public activism and the risks that could come with it – in a new political climate. Some, like Amorim, have been inspired to share their stories for the first time, viewing their voices as the most powerful tool for advocacy. Others have pointed to perceived additional risks and growing hostility toward undocumented immigrants as reason to back out of the public eye.

“We have had a lot more people much more willing to share their story because they sense the urgency of the moment,” says Camila Bortolleto, a founder and campaign manager for the statewide advocacy organization Connecticut Students for a Dream. “But we’ve also seen the exact flip side: people who are much more hesitant and scared to get involved and speak out because of the political climate.”

The moment has presented a challenge for educators, too, as they navigate how best to offer support to their undocumented students.

“Sometimes what’s hard for me is: What does support mean?” says William Lugo, associate professor of sociology at Eastern Connecticut State University (ECSU) and faculty advisor of the Freedom Club, an organization founded by DACA students on campus. “How do I support them in the best way that I can, as effectively as I can? And how do I make sure I’m representing as many [undocumented students] as I can in my support?”

A different environment for sharing

For undocumented students publicly sharing their stories in 2017, the challenges and risks look slightly different than in previous years, says Ms. Bortolleto of Connecticut Students For a Dream. She compares the political atmosphere to that in 2010 – prior to the introduction of DACA – when she first began publicly identifying as undocumented as a student at Western Connecticut State University. It was around that time when large numbers of students began to “come out” as undocumented to share their stories.

“The climate was a lot different because people were a lot more scared back then,” says Bortolleto. “The administration might have been friendlier, but the risks felt a lot more real.”

Seven years later, the youth movement has grown, and “people are more comfortable” publicly identifying as undocumented, she notes, despite new fears brought about by recent anti-immigration rhetoric and steps taken by the Trump administration.

Public opinion polls show broad support for DACA across political lines: 86 percent of respondents in a Washington Post/ABC News poll published in September said they supported the policy.

“Here’s an issue that over the last several years has become a household issue,” says Roberto Gonzales, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. “It’s a segment of the immigrant and undocumented population that has overwhelming and bipartisan support.”

That overwhelming support may explain in part why, in the year since the 2016 presidential election and increasingly in the wake of the Sept. 5 announcement, universities have taken additional steps to create a welcoming, accommodating environment for undocumented students.

Many have made symbolic gestures, declaring their school a “sanctuary campus.” Others, following the news of DACA’s rescission, leapt into action, offering additional counseling support, legal advice, or establishing funds to help students who qualified for the Oct. 5 deadline pay their renewal fees.

“There’s just a heightened awareness and sensitivity that colleges now have about what they can and should be doing to protect undocumented students,” says Candy Marshall, president of TheDream.US, a private organization that provides scholarships to undocumented students at ECSU and other colleges.

Colleges provide safety and support

For undocumented students at ECSU, a public school in Willimantic, Conn., that's home to 104 DACA recipients – and just over 4,000 full-time undergraduate students overall – both institutional and personal support are readily available.

The school is one of a handful across the country that serves as a safe haven of sorts for students from the 15 US states where undocumented residents face significant barriers to getting an education at a public university, such as having to pay out-of-state tuition or not being permitted to enroll at all. Students from these states have been welcomed by ECSU, where they can access scholarships funded by TheDream.US, and find a unique institutional support system that's heavy on one-on-one advising and personalized assistance.

Michel Valencia, a first-year student majoring in psychology, says that growing up in Bridgeport, Conn., where very few of her friends or classmates were undocumented, she didn't often talk about her status. Here, it's a different story.

“When I first came here, I wasn’t expecting to meet a lot of people...who are undocumented,” she says. But “it’s like a whole big community. I feel more [motivated] to tell my story because there are a lot of people like me.”

Support for undocumented students at ECSU comes from the top down: the university's president, Elsa Núñez, has been an outspoken advocate for DACA. Shortly after Mr. Trump's Sept. 5 announcement that he would rescind the policy, school President Núñez led a rally in support of DACA students on campus.

Still, not all DACA students at the school are forthcoming about their status, even – or, in some cases, especially – as the policy has become more politically controversial, says William Bisese, director of the school’s Academic Services Center, who advises students in the scholarship program.

Among the undocumented students at the school, there's a wide range of beliefs, opinions, and approaches to the situation, Mr. Bisese says, noting that the population contains both Democrats and Republicans; activists and those who would rather stay out of the political fray entirely.

Staying quiet not an option

Enilse Ramirez, a junior at ECSU, has never really considered staying out of politics as an option.

Unlike some of her classmates, Ms. Ramirez has years of experience advocating for undocumented Americans, and has long been open about her own status. Between earning her associate’s degree and resuming her education at ECSU, Ramirez worked as a paralegal at an immigration law firm in her native Kansas City, Mo., where she found that being forthcoming about her own undocumented status helped the clients she worked with feel more comfortable.

Since Trump's announcement last month, she's attended rallies, contacted lawmakers, and regularly encouraged friends on social media to do the same. Ramirez sees it as a tiring but necessary way of life.

“It is just an extra hassle on top of anything that any other student has to deal with,” she says. “You have to work, you have to go to school, you have to get your assignments in, and then on top of that, worry about changes in the political world.”

Professor Lugo is conflicted when it comes to students putting themselves out there as public faces of DACA, as Ramirez has. He worries that jumping into advocacy efforts could distract from his students' academic work.

“Am I supporting you one hundred percent even if I feel like you’re exposing yourself unnecessarily?” he wonders. “I know you want to be unafraid, but is this the time for that?”

Focus on schoolwork

Throughout and since the presidential election last November, Mr. Bisese has encouraged the undocumented students he works with to focus their attention on schoolwork rather than politics – partly, he says, because he believed Trump would keep his campaign vow to protect DACA recipients.

The reversal on Sept. 5 didn't change Bisese's approach to advising. He still urges his students to prioritize their schoolwork and to stay out of the public eye.

“There’s not going to be vans pulling up to the campus to grab anybody. I try to buffer that,” he says. “Think about now, think about now.”

President Núñez echoes the importance of taking things one day at a time.

“I said to them, the gift that you can give your families is to stay here,” she says. “Finish the semester. Finish the next semester. Let’s get to March, and let’s see what happens with Congress.”

To help alleviate fears, Núñez reassures students that should the worst case scenario – deportation – occur, the school is prepared to help students find higher education opportunities in their birth countries.

“Even if they ship you back to your country, you can finish there,” she says. “There’s a dream to be had there.”

'We're human, too'

Whether now is the time for exposure is a question that Amorim has given a lot of thought to as of late. Her “coming out” process has been slow but steady, marked by one-on-one conversations with strangers rather than public declarations. Several weeks ago, she found herself telling her story to a worker at a local car dealership who, unaware that he was speaking to an undocumented student, struck up a conversation about illegal immigration and voiced support for ending DACA.

Amorim still harbors many of the same concerns about speaking out that she did before; perhaps even more so now, as the end of DACA as she knows it approaches. But she feels that those concerns make sharing her story all the more necessary.

“It’s important for people to know that we’re human, too,” she says. “We’re your friends and neighbors, and we’re not giving up and going away.”

Dreamers tell their stories

Exploring the link between ‘power’ and predatory behavior

Power doesn't necessarily corrupt, but a sense of entitlement does, and the allegations against Harvey Weinstein offer a window into how power can lead to entitlement if not opposed by a commitment to goals that embrace others.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Amid the cascade of accusations against powerful men of engaging in sexually predatory behavior, it’s natural to wonder, “What was going through these men’s minds?” But perhaps it's better to ask, “What was not going through their minds?” Experiencing power, say psychologists, can have a disinhibiting effect, potentially interfering with individuals’ ability to control their impulses and to read other people’s feelings. Studies show that people higher on the socioeconomic ladder are much more likely to engage in selfish behaviors, such as cutting off other motorists and taking candy that had been set aside for children, and experiments have found that inducing feelings of power in subjects encourages them to lose their manners. The good news is that the negative effects of power can be mitigated by social equality – and that not all people succumb to power's seductive influence. “This is not inevitable,” says Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner, who has studied power dynamics for two decades. “When you give really good people – nice people, kind people – power, they become kinder.”

Exploring the link between ‘power’ and predatory behavior

“I’m used to that,” said Harvey Weinstein, in a telling moment, to the model Ambra Battilana Gutierrez.

It was March 2015, and Ms. Gutierrez was wearing a wire furnished by New York Police Department’s Special Victims Division, in a sexual abuse investigation of the Hollywood producer. As The New Yorker’s Ronan Farrow reported earlier this month, Gutierrez asked Mr. Weinstein why, during a business meeting in his Tribeca office the previous day, he had lunged at her and groped her breasts. This was Weinstein's response: that he was used to it.

How does someone get used to committing sexual assault? While responsibility ultimately falls squarely on the perpetrator, experts say holding power can make it harder to control impulses and easier to justify selfishness, even to the point of disregarding other people’s humanity. The good news is that not everyone is influenced by power quite the same way, and that its effects can be mitigated with social equality.

“Status and power can change the way people think and the way that they act,” says Joe Vitriol, a postdoctoral researcher at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania who studies stereotyping and social cognition. “They perhaps are less concerned about the consequences of their behavior; they feel more entitled to resources.”

In extreme cases, power – defined as the ability to influence the world, particularly through social interaction – can fuel a sense of entitlement over other people's bodies and can smooth the path to sexual impropriety, or, as the cascade of revelations over the past month have shown, sexual assault.

“Money tends to create the context of the impulsive pursuit of sex,” says Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who has studied power dynamics for two decades. “Wealthy people are more likely to have sexual affairs … they’re more likely to flirt inappropriately.”

This impulsive pursuit can include everything from "pursu[ing] relationships" with junior colleagues, as journalist Mark Halperin admitted to last week, inappropriately touching women from behind, as former president George H.W. Bush admitted to last week, to illegally dispensing hypnotic-sedatives to women before having sex with them, as comedian Bill Cosby admitted to in 2005. And it can be prolific: on Saturday, actress Asia Argento posted a list of 82 women who say they were victimized by Weinstein. For director James Toback, that number stands at 310.

That said, people in positions of power can and do wield their power responsibly. Indeed, power typically flows to those who advance the greater good. But as a person rises higher in a social hierarchy, it can become more challenging to maintain a sense of kindness and empathy, a phenomenon that Keltner calls the Power Paradox. And social psychologists have repeatedly shown that power can often cloud people’s moral judgments. Understanding the way power can fuel harmful behavior can also help better mitigate its effects.

Lab experiments, surveys, and observational data reveal that the higher a person is on the socioeconomic ladder, the more likely he or she is to betray a spouse, cheat at a game involving a cash prize, shoplift, and endorse bribery and embezzlement. On college campuses, male athletes, who tend to occupy the upper rungs of the campus social scene, are more likely to admit to acts of sexual aggression. People who drive expensive cars are more likely to cut off other motorists and blow through crosswalks with pedestrians waiting to cross. One experiment even found that rich people are actually more likely than poor people to steal candy that had been set aside for children.

What's more, those who score high on a psychological measure that assesses a person’s likelihood of committing sexual harassment are more likely to unconsciously associate power with sex, which helps explain why many powerful men who make unwanted sexual advances seem surprised to learn that their actions are inappropriate. For those prone to sexual aggression, experts say, simply experiencing power can turn the mind to sex.

This association can lead powerful men to believe that sex is in the air, and that women are happy to be in their presence, an assertion that Keltner doubts. “Our data are suggesting that it’s not necessarily thrilling and exhilarating, and it's more a source of anxiety and shame,” says Keltner.

'Drunk' with power?

Like alcohol, power can have a disinhibiting effect, research shows, increasing a person’s impulsivity, risk-taking behavior, and disregard for social conventions. Power can also interfere with the ability to pay attention to other people's emotions: Studies find that powerful people are less able to “read” the faces of those around them.

Powerlessness, by contrast, inclines people to be more inhibited, more anxious and risk-averse, and more empathetic, although they more readily interpret ambiguous behavior as aggressive.

“You’re sending out these signals of anxiety and fear, and regrettably powerful people don't pick them up, they don't discern that this person they're interacting with is worried or fearful about what might happen,” says Keltner. “I think a lot of problems ensue from that myopia.”

Power and powerlessness are not fixed traits: Indeed, they can be induced in a laboratory setting. In one experiment, known as the “cookie monster” study, Keltner and his colleagues gave groups of three people a group writing task, and randomly assigned one to a position of leadership. Thirty minutes into the task, the experimenter placed a plate of five cookies, allowing each subject to take one cookie and for at least one to comfortably take a second cookie, thus leaving one cookie on the plate for the three people.

Nearly every time, the leaders helped themselves to the final cookie. During the experiment, the researchers noticed that the leaders were more likely to chew with their mouths open, smack their lips, and let crumbs fall on their clothes.

In another experiment conducted in Keltner’s lab by psychologist Paul Piff, now a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, subjects played a rigged game of Monopoly, in which one player, randomly selected with a coin toss, started the game with $2,000 and got to roll two dice, while the other player started with $1,000 and could roll only one die.

Within 15 minutes of play, the researchers observed changes in how the advantaged player behaved. They would speak more rudely, use dominant body language, slam their pieces on the board more loudly, and even hog a bowl of pretzels left out for the players.

After the advantaged player inevitably won, and the experimenters asked them about their experiences, they would attribute their success to their strategy in buying properties, not to the coin toss.

A just world?

“What happens with people of status and privilege – earned or otherwise – is that, because they infer that they’ve acquired that standing by virtue of characteristic qualities unique to them, while discounting the role of chance and situational factors or the presence of others,” says Dr. Vitriol, “they believe that they’re entitled to the benefits that come with that social standing.”

Such rationalization is common. We are disposed to believe that the universe is basically fair, that smart, moral choices bring rewards and that unwise, wrongful actions invite trouble. At its best, this so-called just world hypothesis can give people a sense of control over their lives and can help them better accept negative events, experts say. At its worst, it can justify victim-blaming.

“It may be easier for some people to believe that women and victims of sexual violence and injustice are themselves to blame for these acts than to accept the possibility that we live in a chaotic, uncertain, and, at times, immoral world,” says Vitriol. This thinking, he says, “detracts … from perceiving the perpetrator as wholly responsible for leveraging their position of power and influence to exploit somebody in need.”

Reducing the potentially toxic effects of power will ultimately require making our hypothetically just world a reality. Take Hollywood. Even though women comprise 52 percent of moviegoers, among the top 100 grossing films of 2016, women made up only 19 percent of producers and just 4 percent of directors. “In really unequal situations where women don’t have power or money or authority within an organization there is more of this, ‘I have beauty and I’ll trade it for wealth,’ ” says Keltner. But, he says, “when you move toward more egalitarian power structures with respect to gender, that doesn't work.”

And power does not affect everyone the same way. Power-holders who make an effort to take seriously the interests of the less powerful and link their power to socially responsible goals, as opposed to self-oriented ones, can use their power to effect positive social outcomes.

“This is not inevitable,” says Dr. Keltner. “When you give really good people – nice people, kind people – power, they become kinder.”

Sun City: Las Vegas emerges as standout on solar

Here's something we doubted we would ever be able to write: Las Vegas – the international symbol of reckless excess – is quietly becoming a leader in sustainable energy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

We often associate Las Vegas with extravagance, but the city is quickly also becoming a model for conservation. In December the city announced that all of its municipal and public buildings are now powered by renewable energy, helped in part by the world's third-largest solar energy facility, which went on line last year. In June, Nevada's Republican governor, Brian Sandoval, signed legislation restoring net-metering, which allows people who generate their own electricity to use that electricity anytime, not just when it's generated. These developments, along with other large-scale solar projects and growing public support for energy independence, signal a bright future for a city that gets about 294 sunny days each year. “Nevada is moving forward as progressively as any state in anticipating the advantages and encouraging the deployment of solar power,” says retired US Navy Vice Adm. Lee Gunn, who studies the impact of climate change and renewable energy on national security for Washington-based think tank CNA. “It’s a terrifically exciting place to be.”

Sun City: Las Vegas emerges as standout on solar

For Marcia Bollea, switching to solar energy was a dream come true. A lifelong environmentalist, she had hardly dared hope she would ever see solar panels become affordable for home use. And she’d never imagined it would happen for her in Las Vegas, of all places.

“Social services and environmental issues – those kinds of things weren’t really on the radar when I first moved here,” says Ms. Bollea, a retired nurse who left California for Las Vegas with her son in 1986. “I can’t tell you how thrilled I was when [solar] finally became available to me.”

Bollea’s experience is a small but potent testament to how much the city – and the state of Nevada – has changed. Though gambling and hospitality still make up the heart of Nevadan industry, the past decade has also seen the technological and clean energy revolutions take root in the state. Just outside of Reno sits the most striking symbol of this transformation: the Tesla Gigafactory, a 5-million-square-foot manufacturing facility that opened in 2016 and is meant to supply the company with the lithium-ion batteries it needs to produce electric vehicles.

But in sunny southern Nevada, the focal point of change is solar energy. Last year Acciona, a global infrastructure and renewable energy company, unveiled a 400-acre, 64-megawatt solar power plant in Boulder City, just south of Las Vegas. The third-largest such plant in the world, the facility can power more than 14,000 homes a year – and helped the Las Vegas city government fulfill its promise to power all its municipal and public buildings entirely with renewable energy. The city has since been named among the nation’s top 10 metros leading the way on solar power.

In June, Gov. Brian Sandoval (R) signed nine of 11 clean energy bills passed by the state Legislature. Among them is a measure that restores net metering in Nevada, an issue that was the center of an 18-month tug-of-war between the state’s Public Utilities Commission (PUCN) and clean-energy advocates.

Today, solar sees support from a variety of stakeholders in Las Vegas and across Nevada. Beyond environmentally conscious homeowners like Bollea, there are small businesses looking to boost the economy, libertarians defending energy independence, and community leaders working to improve energy cost and access in low-income neighborhoods.

“Nevada is moving forward as progressively as any state in anticipating the advantages and encouraging the deployment of solar power,” says retired US Navy Vice Admiral Lee Gunn, who studies the impact of climate change and renewable energy on national security for Washington-based think tank CNA. “It’s a terrifically exciting place to be.”

'The Saudi Arabia of solar'

Louise Helton remembers the moment when she decided that her future was going to be in solar. It was in 2005, at a gathering where former President Bill Clinton spoke to Nevadan luminaries about diversifying their economy. “And President Clinton said, ‘If it were up to me, y’all would be the Saudi Arabia of solar,’ ” says Ms. Helton, adopting Mr. Clinton’s Arkansas drawl. “That really clicked with me.”

Now Helton is chief executive officer of 1 Sun Solar Electric, a residential and commercial installation company she and her partner started in 2007 – and one of a slew that has since cropped up in the city and its surroundings. And while Las Vegas’s relationship to solar is not exactly from what Saudi Arabia’s is to oil, the industry has made major strides.

Rooftop solar took off as the cost of residential installation fell. In 2017, homeowners are paying, on average, between $2.87 and $3.85 per watt – compared to about $9 per watt in 2005. It’s still not super affordable, considering the average American home runs on about 5 kilowatts of power and would need a system with a price tag of more than $11,000 after tax credits to install.

But analysts say the cost is likely to keep dropping. Leasing models also gave homeowners an option that doesn’t involve cash up front. In Vegas, that has meant a surge in installations among residents eager to turn their city’s relentless sunshine to their advantage.

What really transformed the solar landscape in southern Nevada are the large-scale projects. 2007 saw the construction of a 14-megawatt solar power station at Nellis Air Force Base, just northeast of Las Vegas, marking a milestone in the US military’s march toward renewable energy. Last year, Nellis – home to the world’s largest advanced air combat training mission – added another 15-megawatt solar array on its grounds.

Not to be outdone, casinos like MGM Resorts and Wynn Las Vegas began transitioning to solar despite facing hefty fees for leaving NV Energy, the state’s main utility. Mandalay Bay, an MGM property, now boasts the largest commercial-rooftop solar array in the country – a 28-acre system that could power 1,300 homes.

The Las Vegas city government also pledged to run all its facilities – including parks, streetlights, and community centers – on 100 percent clean energy through a combination of credits and direct generation. Around 2010, the city began installing solar panels in parks, on parking structures, and on its wastewater treatment plant. The most iconic display is City Hall, a seven-story paneled glass structure built in 2012 with a grove of solar “trees” arrayed proudly along its front plaza.

The goal became reality last year, after the Boulder City solar plant went online. The facility dedicates a portion of the power it generates to the city.

“This really exemplifies our commitment to sustainability,” says city planner Marco Velotta.

Strange bedfellows

Rooftop solar advocates across the state say the PUCN’s decision to end net metering in 2015 was a hard blow to the industry. Although a bill passed in the 2017 legislative session reversed the ruling, it will likely take years to regain lost ground, proponents say. Advocates are also disappointed at the governor’s decision to veto two bills: one that would have increased the state’s renewable portfolio standard to 50 percent by 2030, and another that would have expanded community solar use in the state. Meanwhile the debate over whom solar power benefits, and how, rages on. And as of 2015, renewables only made up of about a fifth of Nevada's electricity generation – with solar only a fraction of that.

Still, the industry is on the upswing. A wide range of stakeholders have found reason to support solar expansion in the region, outside of the fact that Vegas sees about 294 sunny days a year.

Some of it has to do with consumer support of clean energy. Polls show that a majority of Nevadans stand behind the transition to clean energy because of the environmental benefits, the economic potential (clean energy jobs saw a 9.5 percent bump in Nevada in 2016), the relative cost savings, or some combination of the three.

At least as powerful a driver is energy choice.

“They’re an independent group of folks,” Helton says of her fellow Nevadans. “They like to be able to take care of things themselves. If you can provide energy for yourself, that appeals mightily to people.”

“The fact that NV Energy has a monopoly on the delivery and distribution of power in Nevada is basically the antithesis of the free market ideal,” adds Sam Toll, communications director for the Libertarian Party of Nevada. “The notion of pushing technology in the free market with respect to solar power, and advancing the capacity and efficiency of panels and systems, is spectacular” – though he draws the line at government actions that favor solar, or any industry, above others.

The military’s presence in the state adds another dimension to the solar power argument. The Navy, Army, and Air Force have all invested increasingly in solar and other renewables in a bid to make the military more efficient, economical, and resilient.

“There are a lot of people around the country who believe that there is a coming transition from fossil fuels to renewables, but are reluctant to speak about it because it’s tied to climate change,” Vice Admiral Gunn says. The national security argument helps pave the way for “a sensible, well-reasoned conversation about advanced energy,” he says.

Such collaborations have led some to hold high hopes for the solar community in the region.

“Our vision for Nevada is that we will get to demonstrate to the rest of the country what investing in clean energy means for our economy, for our environment, for our pocketbooks ... when you do it right,” says Andy Maggi, executive director of the Nevada Conservation League. “I also think it is a demonstration of the power and the importance of local and state governments in really driving the clean energy revolution.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Tanks in Barcelona’s streets? Not on EU’s watch.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

With Spanish authorities seizing control of the government in the autonomous region of Catalonia, both sides are wondering if violent conflict is inevitable. So far, sentiments for peace seem strong, in large part because of one important background player: the European Union. Several moves by Catalan secessionists, such as a referendum and a declaration of independence, have been made outside Spain’s Constitution. But Spain’s government has also erred – for example, in using police violence during the Oct. 1 referendum vote. Any confrontation that leads to violence will only hurt both sides, especially in their critical relationship with the rest of Europe. Rule of law and economic ties are exactly the EU’s foundations. The Union was designed to suppress the kind of rampant nationalism that challenges borders and leads to war. The higher principles of the EU are at work in this crisis, even if they may be hard to see.

Tanks in Barcelona’s streets? Not on EU’s watch.

Spain’s crisis over the independence bid of its Catalan region keeps escalating in its legal and electoral drama. Yet with Spanish authorities now seizing control of the autonomous region’s government, both sides are wondering if a violent conflict is inevitable. So far, sentiments for peace seem strong, in large part because of one important player in the background: the European Union.

The continent’s relative peace since World War II has been rooted in the EU’s promise of shared prosperity and common democratic principles. Several moves by Catalan secessionists in recent weeks, such as a referendum and a declaration of independence, have been done outside Spain’s Constitution. This is in sharp contrast to the use of rule of law by other places in the EU that had attemped to gain independence, such as Scotland in a failed 2014 referendum.

Spain’s government itself erred in using police violence during the Oct. 1 referendum vote in Catalonia. Nearly 900 people were injured as police tried to suppress the voting. Widespread reaction to this official crackdown, especially among top EU officials, has now helped temper any tendency for more violence.

“I hope the Spanish government favors force of argument, not argument of force,” tweeted European Council President Donald Tusk.

The ousted president of the Catalan government, Carles Puigdemont, has called for “democratic opposition” to Spain’s takeover. And many pro-independence Catalans plan massive civil disobedience. Yet any confrontation that leads to violence will only hurt both sides, especially in their critical relationship with the rest of Europe. They need only recall the tough economic sanctions against Russia for its use of armed force to take Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula.

To help defuse possible tensions, Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has called for a Dec. 21 election of leaders for Catalonia. The vote will not only be constitutional but may officially reveal what the pollsters have found: Most Catalans prefer to stay with Spain, although with greater powers of autonomy. In addition, Catalans have seen more than 1,000 businesses leave the region as tensions have grown.

Rule of law and economic ties are exactly the EU’s foundations. The Union was designed to suppress the kind of rampant nationalism that challenges borders and leads to war. The higher principles of the EU are at work in this crisis, even if they may be hard to see.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Excellence at school

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

School can be an exciting place where stimulating opportunities meet up with energetic learners. For some, the path to success can seem difficult or even impossible. But everyone has an innate ability to express qualities such as intelligence and creativity. These are qualities we reflect from God, divine Mind, who created all of us as complete, not lacking. Even a small understanding of this can protect children – and adults – from limits and stereotypes that might seem to block opportunities to succeed at school and beyond.

Excellence at school

School can be such an exciting place to be: Stimulating opportunities meet up with energetic learners. But what if there are problems at school? Is the path to success just inevitably hard for some?

When our daughter was in the third grade, her teacher devoted the year to character-building, and the curriculum focused on the students writing and performing an opera together. By year’s end, they had refined skills of cooperation, respect, and selflessness, but they hadn’t learned much math. When she started the fourth grade, our daughter fell behind, and she struggled to pass any of her math tests. At the first parent-teacher conference I was told that if she did not do well on the next test, she would be placed in a class for slow learners.

Of course I wanted to do all I could to help my daughter, including with her need for the necessary academic teaching of math. Many times before, though, I had found that acknowledging her inherent spirituality helped me better support her expression of youthful energy and intelligence in the most productive way, whether at school or elsewhere. So as I drove home from the meeting with the teacher, I prayed.

Christian Science explains that every one of us is the complete spiritual expression of God, divine Mind. The uniqueness and intelligence of this limitless Mind are expressed in and as its creation. No one is simply one of a series on an assembly line. Our identity is secure in Mind, including opportunities to express qualities such as originality and ability.

I considered how Mind manifests its attributes throughout creation. Everyone has an innate ability to discover the brilliance of Mind and express qualities such as understanding, intelligence, and logic. God’s attributes are fully individualized in us – not parceled out in bits and pieces. At God’s table, everyone is fully served, even while each one’s experience at the table is naturally one of a kind. Even a small understanding of this can protect children – and adults – from limits and stereotypes that might seem to block opportunities to succeed.

I continued praying with these ideas, recognizing that God had prepared a path forward for our daughter to express her natural intelligence. This lifted any fear that her potential could be thwarted because her previous school experience had been unique, or for any other reason.

That evening, I talked to our daughter about the qualities of Mind that God has given her to express, and encouraged her to know herself as the intelligent reflection of Mind. I never told her what the teacher had said. The next day she passed the math test, and no more mention was ever made of remedial classes or being labeled as “slow.” Rather, from that point on she continued to study and apply herself, and she always got exceptional grades in math.

We can pray to recognize everyone’s infinite spiritual potential to express intelligence. Everyone has the inherent right and ability to demonstrate excellence at school and beyond.

A message of love

A new Eurasian connection

A look ahead

Thank you for reading today. Please come back tomorrow, when staff writer Harry Bruinius will look at how the era of free online news might be evolving into a model more like Netflix's.