- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for December 18, 2017

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Christmas is a peculiar topic about which to have a war. Yet in certain quarters of the media, that appears to be precisely what is going on. Businesses that wish “Happy Holidays” are seen as betraying treasured Christian traditions. Meanwhile, wishing “Merry Christmas” to those who don't celebrate it can be seen as insensitive and overbearing.

Must Christmas be sacrificed to political correctness? Or must it be forced on others against their will? The “war” seems to set up an either/or choice.

But the spirit of Christmas is not overbearing. The child whom Christmas commemorates was born in a barn after his pregnant mother was turned away by everyone in the town.

And Christmas is not in need of promotion. The original story was announced to the shepherds in the field and wise men from the East without electric-powered twinkle lights or “50 percent off” sales.

Christmas is the promise of “on earth peace.” It is the commitment of goodwill toward all. These terms can't lead to a “war.” They should, in fact, be an antidote to it.

Today, our five stories include two on the nature of progress: For women in Africa or for conservationists trying to save elephants, how do you move forward when the way seems blocked? We also look at how the Muslim right is viewing the United States' Jerusalem move.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How Trump's security agenda echoes election campaign

President Trump made a big deal out of the release of his National Security Strategy Monday. The reason seems clear: It is intended as a clear break from the past and a robust statement of his worldview.

-

Harry Bruinius Staff writer

Per congressional legislation, presidents are supposed to issue a formal National Security Strategy every year. Most don’t. And when they do, presidents don’t normally give a speech about them. But President Trump is nothing if not a mold-breaker, and on Monday he went to a federal office building and delivered a speech on his newly released NSS that might have been lifted from the 2016 campaign. It emphasized the need to control immigration, the faults of his predecessors, and the defining aspects of his own election – all while underscoring a view of the world as a dangerous place where the United States needs to aggressively carve out its advantage. It represents an attempt to define a practical realism for the modern world. It lessens the importance of spreading democracy and working with alliances and emphasizes the need to protect US economic interests in a world where other nations always have their elbows out. In the words of one analyst, “This is a clear break from 70 years of American statecraft. It is a uniquely assertive nationalist approach to the way America engages the world.”

How Trump's security agenda echoes election campaign

President Trump’s new National Security Strategy might be summed up by the first subhead in its introduction: “A Competitive World.”

If the 56-page document has a defining theme, it is that the globe is a dangerous place, and the United States needs to shove its elbows out more in the struggle for comparative advantage. It plays down the importance of multilateral cooperation (though it still backs traditional US alliances such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization). It explicitly emphasizes such domestic priorities as economic prosperity and jobs as key national security components. A stock phrase used by virtually all presidents since Harry Truman, the US as “indispensable leader” of the free world, is largely missing from Mr. Trump’s new NSS.

“This is a competitive vision. It is not a leadership vision,” says Gordon Adams, former White House defense budget official and current distinguished fellow at the Stimson Center, a nonpartisan security policy research organization in Washington.

It does not promote democracy per se, and indeed seems to indicate little concern for how other countries are governed. What matters most is how the behavior of those other countries affects the welfare of the American people, an attitude the strategy defines as “principled realism.”

“This is a clear break from 70 years of American statecraft. It is a uniquely assertive nationalist approach to the way America engages the world,” says Professor Adams, who teaches foreign policy at American University.

'A competitive vision'

National Security Strategy documents are generally interesting efforts whose final product belies their name. Mandated by 1986 congressional legislation, they are not actual national strategies that spell out specific policy goals and match those goals with resources and detailed timelines. Instead, they tend to be long and detailed summaries of approaches to the globe. They tend to be serious speeches, elongated.

They are supposed to be issued annually, but recent presidents have not met that goal. Barack Obama issued two in eight years in office. George W. Bush issued one.

The Trump administration should be commended for producing an NSS so early in its term in office, say some Washington experts. National security adviser H.R. McMaster and a National Security Council aide, Dr. Nadia Schadlow, pulled it together.

“It is important that this is a first year document,” says Anthony Cordesman, the Arleigh Burke Chair in National Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

The lengthy NSS released by the White House is divided into four main sections: protecting the homeland and way of life, promoting American prosperity, demonstrating peace through strength, and advancing American influence in an ever-competitive world.

The strategy depicts both China and Russia in relatively harsh terms, despite Trump’s generally good relations with the leaders of both nations. Both countries “challenge American power, influence and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity,” the document says.

It also warns against the general belief that “engagement with rivals” will turn them into “trustworthy partners” – possibly a slap at former President Obama’s dealings with Iran and Cuba.

The US has too often looked at relations with other countries as being binary, either peaceful, or warlike, according to the Trump strategy. Actually, the world is in a state of “continuous competition,” according to the NSS.

“We will raise our competitive game to meet that challenge,” says the document.

Overall, the Trump NSS has some familiar parts and some not-so-familiar parts, according to Adams of the Stimson Center.

Its non-promotion of democracy is one unfamiliar part, he says. So is its chilly attitude toward multilateralism, with its talk of “free riders” in military alliances and insistence on allies paying up.

Conspicuously missing from the document, says Adams, is any treatment of how the US will have to adapt to a rapidly rebalancing world, with China a rising superpower, and other nations such as Turkey increasingly playing an independent role.

“Everybody is playing outside the boxes of the old system ... that is not recognized,” says Adams.

The nuance is in the details

In Dr. Cordesman’s view, politics in the US has become so polarized that people are judging the National Security Strategy on the extremes of the document rather than its overall tone and meaning.

Yes, the Trump NSS talks about “America First,” a slogan from his campaign that critics say carries more than a tinge of isolationism. But it’s not the same thing, according to Cordesman.

“You look at what Trump says about America First, and most of it is very international in character and has a great deal of continuity with, say, US national security policy under Clinton, Bush, and in many ways even under Obama,” he says.

The rhetoric of foreign policy often does not match the reality, he says. In NATO and other strategic partnerships, the Trump administration has made very few changes, and in some ways has actually strengthened the American presence overseas.

“I think almost all of our allies are going to find this document reassuring,” says Cordesman. “But the truth is, most of them probably see Secretary [of Defense James] Mattis, General McMaster, and Secretary [of State Rex] Tillerson as figures in which basically they see the same basic national security policies that they would have seen under Bush – or even Reagan for that matter.”

That may be true, but the NSS document is not the only thing allies are closely studying, says Julianne Smith, senior fellow and director of the Transatlantic Security Program at the Center for a New American Security. They are closely studying the president’s behavior as well, and that often sends messages that are at odds with the most sober language of his senior staff and Cabinet members.

Trump’s tweets and words have put very little value on NATO and other alliances, for instance.

“So there are definitely parts of [the NSS] that don’t ring true if you closely watch what the president has said over the last year,” says Ms. Smith. “It’s hard to assume that he would agree with everything that’s in here.”

Indeed, Trump’s Monday speech on the security strategy touched on many things not mentioned in the document. Much of it could almost have been a campaign speech from 2016, as it emphasized the need to control immigration, the faults of Trump’s predecessors, and other more emotional aspects of his approach to politics.

Share this article

Link copied.

US move on Jerusalem reignites Muslim Brotherhood

Now that President Trump has recognized Jerusalem as the Israeli capital, the world is recalibrating. The big news Monday was a failed United Nations attempt to force Mr. Trump to abandon his plan. But in the Middle East, a bigger emerging story line might be the stirring of a key player on the Muslim right.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

The conservative Muslim Brotherhood has stood against the Arab-Israeli peace process for decades. During the first Palestinian uprising in 1987, the Brotherhood’s Egyptian branch formed the militant movement Hamas. Its intent: establishing an Islamic Palestinian state in the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel. And Jerusalem, say Brotherhood members and supporters, is a symbol more important to Muslims than Mecca. So when President Trump recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, he was also throwing a lifeline to an organization suppressed in Egypt, outlawed in much of the Gulf, and marginalized elsewhere in the Middle East. The Arab world has reacted angrily to Mr. Trump's decision, but analysts say the Brotherhood’s strong language and decisive action leading protests have filled a void left by regimes that have condemned the declaration but are cautious not to strain ties with the United States. After five years of attacks by secularists, leftists, minorities, and others, the Brotherhood seems to be getting broad support. Says a Brotherhood member in Jordan’s parliament: “On the issue of Jerusalem, there are no two Jordanians who disagree, no two Arabs who disagree, no two Muslims who disagree.”

US move on Jerusalem reignites Muslim Brotherhood

President Trump’s declaration recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital has elicited criticism and outright condemnation from world leaders ranging from traditional US allies to long-time adversaries.

In the Arab world, scene of multiple demonstrations since Mr. Trump’s declaration, the reaction has been especially angry and has created one clear political winner: the conservative Muslim Brotherhood.

The Islamist organization – violently suppressed in Egypt, outlawed in much of the Gulf and marginalized elsewhere in the region – has stood against the Arab-Israeli peace process and negotiations over Jerusalem for decades.

Analysts and politicians say the Brotherhood’s strong language and decisive action have filled a void left by Arab regimes that have condemned the declaration but are cautious not to strain ties with the US and Israel.

The movement, which has witnessed a stunning rise and rapid fall since the Arab Spring, has been given a new lease on life as it attempts to rebuild its credibility with the Arab street. It is now setting its sights on a return to the political scene as it leads popular protests in multiple Arab states.

In Jordan, where the Brotherhood has been largely absent from the streets for three years, the movement spearheaded nationwide protests against the US and Israel, organizing the largest protest Jordan has seen in nearly a decade.

In Kuwait, the Brotherhood’s Islamic Constitutional Movement led protests against the Trump declaration, with the group’s members of parliament even calling on the Kuwaiti leadership to reconsider its relationship and investments in the US if Washington refuses to retract the decision.

Brotherhood-aligned clerics in Libya, Qatar, and elsewhere have also denounced the US and Israel and have urged popular action.

Search for a message

After calling for freedoms and democratic reforms during the Arab Spring in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Jordan, and elsewhere, the Brotherhood recently has struggled to come up with a message to appeal to Arabs sick of revolutions, instability, wars, and extremism.

After five years of being attacked by secularists, leftists, minorities, and regime loyalists, the Brotherhood suddenly seems to be getting support from all segments of society.

“The Arab Spring exposed our differences: when we demanded reforms and freedom, other groups and people disagreed with our priorities and approach,” says Saud Abu Mahfouz, an MP from the Brotherhood’s Islamic Action Front party in Jordan.

“On the issue of Jerusalem, there are no two Jordanians who disagree, no two Arabs who disagree, no two Muslims who disagree.”

According to Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington and co-editor of “Rethinking Political Islam,” “The Brotherhood has been on its back foot for some time and has struggled to adapt to the post-Arab Spring environment and find a political high ground where it is difficult for people to take issue with them.”

Jerusalem, he says, “is one of those issues.”

Religious claims

While the Brotherhood’s stances have evolved over time, such as accepting a civil state, the role of the Quran as a source of law, and women’s and minorities’ rights, its language and position on Jerusalem have remained largely unchanged for decades.

Since the Brotherhood’s founding in Egypt in 1923, Jerusalem and the Palestinian cause have been at the core of its appeal, rooted both in its ideology and Islamic claims to the holy city.

Muslims originally prayed facing Jerusalem, where tradition holds that Muhammad ascended to heaven. Jerusalem’s Old City is also the location of the Al Aqsa Mosque, the third-holiest site in Islam. The holy city is the burial site of thousands of prophets and companions to Muhammad, and the city plays an important part in the end-of-days beliefs of Muslims.

Jerusalem, say Brotherhood members and supporters, is a symbol more important than Mecca.

Hassan al-Banna, the founder of the Brotherhood, sent fighters to Jerusalem to aid the Arab uprising in British-mandate Palestine in 1936, and established several branches across Palestine in the 1940s.

Opposition to Oslo

During the first intifada in 1987, the Brotherhood’s Egyptian branch formed the militant Palestinian movement Hamas with the intent of “liberating” all of Israel and establishing an Islamic Palestinian state in the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel.

The Oslo peace accords between Israel and Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization in 1993 gave a new mission to Brotherhood branches across the Arab world, particularly in the occupied Palestinian territories and in neighboring Jordan.

The Brotherhood stood against the peace process and any Arab normalization with Israel. Its branches in Jordan and Egypt opposed the two countries’ treaties with Israel, and used the talks’ failure to end the Arab-Israeli conflict as a wedge to drive between Arab regimes beholden to the US on the one hand, and their publics who were wary of the peace process on the other.

The movement’s disciplined messaging on Palestine has been noticed by the younger generation, many of whom had not yet come of age when the Arab Spring erupted six years ago.

“I am not political, I am not part of a party, and I have no ideology,” says 17-year-old Osama Bashnaq, who was protesting for the first time in a Brotherhood-led protest in downtown Amman on Dec. 8.

“But the Brotherhood have been the strongest standing by Jerusalem. They deserve our support.”

Boost for Hamas

Perhaps no Brotherhood branch has seen a turnaround in fortunes like Hamas. Recently, cracks were showing in the group’s hold on an increasingly marginalized and economically depressed Gaza Strip; in January, thousands of Gazans protested against Hamas’s administration and ongoing electricity cuts.

As recently as September, in a head-to-head matchup for president, 50 percent of Palestinians polled said they would choose the embattled and deeply unpopular Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas over Hamas’s Ismail Haniyeh, who was backed by 42 percent of respondents, according to the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR).

In the wake of the Trump move on Jerusalem, Palestinian voters shifted, saying they would prefer Mr. Haniyeh over Mr. Abbas by a 53 percent to 41 percent margin, according to a PCPSR survey taken days after the declaration.

The same poll saw that the percentage of Palestinians calling for armed resistance – long advocated by Hamas – has risen from 35 to 44 since the declaration.

“I think Hamas benefits from being able to say that they were the ones who were right to be opposed to the peace process. They can point to this announcement as the evidence of the failure of the peace process or that the peace process never existed in the first place,” says Mr. Hamid at Brookings.

Next steps

Yet Islamists stress that they are not using the issue to undermine or even oppose Arab regimes.

“We are only strengthening the official Jordanian response, Arab response, and Islamic response,” says Zaki Bani Irsheid, who masterminded the movement’s 2016 electoral campaign in Jordan.

“We are not replacing it or dictating it.”

Yet if the US does not rescind its decision, the Brotherhood in Jordan is ready to push further. Its 14 MPs in Jordan have led an effort to debate the kingdom’s 1994 peace treaty with Israel, a motion that was passed unanimously. The Islamist bloc is demanding Jordan close the Israeli Embassy in Amman and aid all “resistance movements,” including Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and Al Aqsa Brigades. Brotherhood leaders say privately they want Jordan to reopen Hamas’s offices in Amman and downgrade ties with the US.

Expecting dramatic action in the near future is “unrealistic,” the leaders say, but there’s a chance of shifting the narrative for future generations.

“The next generation will be the ones to realize the will of the Islamic and Arab nation,” says Mr. Abu Mahfouz, the Jordanian MP. “And we are patient.”

Florida election mystery: the case of the destroyed ballots

For the moment, questions about the safety and fairness of American elections center mostly on allegations of Russian interference. But an inquiry in Florida shows how things can become contentious even without foreign interference.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The Democratic primary in Florida’s Broward County was being closely watched across the United States in August 2016. A month earlier, amid bitter controversy, incumbent Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz had been ousted as chairwoman of the Democratic National Committee over allegations that she and other party officials had rigged the presidential primary process to favor Hillary Clinton over Bernie Sanders. Now, enraged Sanders supporters would have an opportunity to fight back by voting for her opponent, Tim Canova, a Sanders ally. After Ms. Wasserman Schultz won by a margin of 6,104 votes, Mr. Canova did not contest the result, but he later sought to examine the ballots, and in June, he filed a lawsuit asking a judge to order the ballots be made available for inspection. Yet despite the ongoing litigation, Broward’s supervisor of elections in September ordered the ballots destroyed, according to papers filed in circuit court here. Their destruction comes at a time of intense public alarm over potential attempts by Russia and others to hack into US election systems. One safeguard against such efforts is the ability to conduct robust audit procedures based on a close examination of paper ballots. “When something like this happens, where all the ballots are destroyed, it completely undermines people’s faith in the system,” Canova says. “What is the Broward supervisor of elections hiding?” Wasserman Schultz’s office has offered no statement.

Florida election mystery: the case of the destroyed ballots

A South Florida law professor, running to unseat Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz, is calling for a federal investigation into the destruction of all ballots cast in the August 2016 Democratic primary in Broward County.

The challenger, Tim Canova, has made repeated public-records requests and filed a lawsuit seeking access to paper ballots cast in his unsuccessful race last year against the former Democratic National Committee chair in Florida’s 23rd congressional district.

A statistical analysis of the primary conducted last year suggested the election results were “potentially implausible.”

Over the past year, the Broward supervisor of elections, Brenda Snipes, has taken no action on requests by Mr. Canova and journalist and documentary filmmaker Lulu Friesdat to examine the ballots. Instead, Dr. Snipes has urged a judge to throw Canova’s lawsuit out.

Despite the pending records requests and the ongoing litigation, Snipes ordered the ballots and other election documents destroyed, according to papers filed in circuit court here.

“When something like this happens where all the ballots are destroyed, it completely undermines people’s faith in the system,” Canova says in an interview.

“What is the Broward supervisor of elections hiding?” he asks.

The Monitor reached out to Snipes and to her lawyer. They did not respond to requests for comment.

Congresswoman Wasserman Schultz’s office offered no statement on the issue.

The supervisor’s destruction of the documents comes at a time of intense public alarm over potential attempts by Russia and other foreign powers to hack into American election systems. One safeguard against such efforts is the ability to conduct robust audit procedures based on a close examination of paper ballots cast by voters.

Election experts agree that the lack of a paper trail verifying voter choices undercuts the ability to identify systemic election fraud and might make such fraud impossible to detect.

The Aug. 30 Democratic primary in Broward was being closely watched across the country. A month earlier, amid bitter controversy, Wasserman Schultz was ousted as chairwoman of the DNC. She was removed over allegations that she and other party officials had rigged the Democratic presidential primary process to favor Hillary Clinton over Bernie Sanders. The pro-Clinton fix was first divulged in DNC emails allegedly obtained by Russia-backed hackers and released to the public in the months leading up to the election.

Wasserman Schultz is a Clinton ally. Canova is a Sanders ally.

The Democratic primary in Florida’s 23rd district was seen by some as an opportunity for enraged Sanders supporters and other voters to fight back against DNC favoritism – by voting for Canova.

Nonetheless, Wasserman Schultz defeated Canova, winning 26,608 votes (56.48 percent) versus Canova’s 20,504 votes (43.53 percent). The seven-term incumbent’s margin of victory was 6,104 votes.

Florida's regulations on ballots

After the election Canova did not contest the result, but later contacted the election supervisor’s office seeking to examine the ballots. Two initial public-records requests were submitted in November 2016 by Ms. Friesdat. She submitted a third request in March under Florida's Public Records Act. Canova later joined the requests and in June, filed a lawsuit asking a state judge to order Snipes to show the ballots.

Snipes’s order to destroy the requested documents is dated Sept. 1, 2017. It authorized the destruction of 106 boxes containing vote-by-mail certificates.

In addition, the order authorized the destruction of 505 boxes of in-person cast ballots and 40 boxes of early-voting ballots.

In total, the destruction order called for election department officials to locate and dispose of 688 boxes containing 894 cubic feet of documents, according to a copy of the order.

Under Florida law, ballots and other election documents are public records that must be made available for inspection by members of the public “at any reasonable time, under reasonable conditions.”

One limiting factor is that only the supervisor of elections or designated staff members are permitted to physically handle the ballots. But the law establishes that ballots are public documents and members of the public are entitled to see and examine them.

In addition, Florida regulations require retention of records related to a federal election for 22 months. That would mean that documents from the August 2016 Democratic primary election would not become eligible for routine destruction until late June 2018.

Florida regulations also prohibit destroying records that are the subject of a public-records request or lawsuit. “When a public agency has been notified that a potential cause of action is pending or underway, that agency should immediately place a hold on disposition of any and all records related to that cause,” the regulations say. (The added emphasis is written into the regulations.)

Dispute over scanning ballots

Friesdat's and Canova’s requests for access to the ballots bogged down in a dispute over whether each ballot could be “scanned” into a digital system by Canova’s team for analysis. Snipes and her lawyer refused to allow the documents to be scanned, insisting that use of such technology was not part of their public-records procedure.

In addition, they took the position that the Canova team could view each ballot as it was held up by an office staff member, but they would not be permitted to videotape the process or have a court reporter produce a transcript during that review process.

In April, Snipes’s office advised the Canova team its request to view the election records would cost $71,868.87 in government fees, according to court documents.

Susan Pynchon of Florida Fair Elections Coalition, an elections watchdog group, says Broward County is famously uncooperative.

“We’ve always had an impossible time dealing with Broward County,” she says. “It is very difficult to get records from them.”

She noted that during the August 2016 primary, Broward County’s election results were posted online too early, causing some county websites to crash.

Ms. Pynchon says that an election vendor set up a special webpage to allow the Broward elections office to monitor the primary election results as they were being collected. Such an arrangement is unusual, she says.

“This horrifies me, the thought of them having these results streamed to them online ahead of the final results,” Pynchon said.

Lawsuit still pending

As supervisor of elections, Snipes is an elected official.

In November, Snipes herself was on the ballot as an unopposed Democrat seeking her fourth term as elections supervisor.

She received more votes than any other candidate on the ballot in Broward County – 657,167 votes, or 96.71 percent of votes cast. That is nearly 104,000 votes more than Mrs. Clinton received in Broward.

Canova’s lawsuit is pending before Broward Circuit Judge Raag Singhal. The judge has yet to rule on whether Canova is entitled to examine the ballots and, if so, under what circumstances.

Snipes’s lawyer filed a motion in July urging Judge Singhal to throw the case out. A hearing on that motion was held in October – a month after the documents were already destroyed.

Canova’s lawyer and the judge were not informed of the destruction of the ballots until a Nov. 6 hearing, according to court documents.

“The defendant’s counsel told the court and [Canova’s] counsel that [Canova] could inspect and copy the public records during the October 3, 2017 hearing…, but failed to advise the court or [Canova] that records were destroyed on September 1, 2017 – resulting in [Canova] spending significant sums of money to inspect and copy records that no longer exist,” Canova’s lawyer, Leonard Collins, wrote in a motion to the court.

“It is beyond perplexing,” Canova says. “Why would somebody commit felonies and risk criminal liability to prevent turning over ballots?”

He adds: “The public-records law is very clear. These are public records.”

The value of paper

The primary purpose of maintaining paper ballots after an election is to facilitate a reliable audit of election results.

Election security experts warn that computerized ballot tabulators – such as those used in Broward County – can be hacked and reprogrammed to award more votes to one candidate and withhold votes from another.

The safeguard against such hacking is to use paper ballots. If necessary, the paper ballots can be counted by hand and the hand-counted vote totals compared to those recorded on computerized tabulators.

If the tabulators were hacked or malfunctioned, the paper ballots would provide a reliable paper trail to determine the correct outcome of the election, security experts say.

Canova says the elections office has retained its own scanned, electronic copies of the ballots from the 2016 primary. But computerized images don’t offer the same high level of protection as paper ballots, he says. Computerized images can be manipulated in ways that paper ballots cannot, he adds.

“We are left dependent on scanned ballot images created and sorted by scanning software that requires inspection by software experts,” Canova says. “But the scanning software is considered proprietary software and is routinely protected from such independent inspection and analysis.”

'We'll schedule a time'

Although Snipes did not respond to requests for an interview for this article, she was asked about Canova’s request for access to the ballots during an earlier interview with the Monitor in October.

She was asked why it was necessary for Canova to file a lawsuit simply to view election ballots.

“It has to be scheduled,” she said. “We get it on the schedule and arrange the staff and then he can come in and review the ballots.”

The Monitor: “But they sued to have that [access.] And you are fighting them.”

Snipes: “Absolutely not. As long as it is a public-records request he can have the ability to come in and look at the ballots. We are not fighting Tim Canova. We’ve been working with them for a very long time. But we are not fighting them.”

She said the Canova team wanted to video record the ballot examination process. They wanted to make it into a “big production,” Snipes said. “A public-records request is not a big production.”

Then Snipes added: “We’ll see where it goes, but we’ll schedule a time for them to come in and see the ballots.”

The comments were made Oct. 19, more than a month and a half after Snipes signed the order to have the ballots destroyed.

To protect Africa's girls, local voices matter

What does it take to change deep-seated traditions? Threats and laws only go so far. Often, it's the example of a trusted friend, a neighbor – someone who understands your experience – that makes the difference, as this story shows.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Two hundred million women have undergone some form of female genital mutilation, or FGM – including most girls Aminata Mané grew up with here in southern Senegal. But when her in-laws summoned Ms. Mané’s eldest daughter for the rite, a long-buried instinct clawed its way to the surface. “I told them no – absolutely not,” she says. That was 33 years ago. Since then, she has told her cutting story dozens of times, perhaps hundreds: in packed rooms and under baobab trees, on the radio, and at her own kitchen table. FGM has become something of a cause célèbre in the international advocacy world. Dozens of countries have banned it. But without local buy-in, activists and researchers say, punishment does little to change people’s minds. The message must come from women like Mané, making it harder to argue that the push against FGM is simply an import of a finger-wagging West. “You have to be part and parcel of that culture,” says Mary Small. “When people know you accept them, that you are not condemning them for how they live, they begin to listen.”

To protect Africa's girls, local voices matter

It was the biggest party Aminata Mané had ever been to, a riot of colorful dresses and exuberant dancing. There were enough fluffy piles of rice and roasted sheep’s meat for the entire village to eat until their stomachs hurt – and it was all to celebrate her.

But Mrs. Mané, who was 11 at the time, couldn’t stop crying. She cried as her aunt led her from the ceremony into the party, whooping and cheering. And she cried as her mother leaned over her and whispered how proud she was. You were so brave, she said. She kept crying through the congratulations and the dances and the dinner, right up until the moment she was finally allowed to go home.

“How can you enjoy a party when you are in pain like that?” she says. “But it wasn’t only physical pain – I cried because I didn’t want this, I didn’t choose this.”

For years, Mrs. Mané rarely talked about that day, when she and several other girls from her village returned from an initiation rite known locally as xarafal jiggeen, and in the parlance of the global aid world as FGM, or Female Genital Mutilation.

What was there to say? It had happened to her, just like it had happened to every other girl she knew in her community in Senegal’s southern Casamance region. It was as ordinary as the crackling call to prayer at the local mosque, or cooking chebujin, spiced tomato rice and fish, on a Sunday morning.

And so afterwards, they had all simply carried on.

It wasn’t until nearly two decades later, when Mané’s in-laws summoned her eldest daughter for the rite, that a long-buried instinct clawed its way to the surface.

“I told them no – absolutely not,” remembers Mané, who is now the president of Santa Yalla, a local women’s advocacy group. “I know the psychological pain I still suffer from this, and I cannot let her go through that.”

Globally, more than 200 million women and girls have undergone some variation of FGM, according to the World Health Organization, most of them scattered across some two dozen countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Many of these women go on to suffer severe medical complications, often during childbirth. Sex is frequently unbearably painful.

In recent decades, their plight has become something of a cause célèbre in the international advocacy world, sprouting dozens of polished NGOs and high-level promises from bodies like the United Nations, which has pledged to end the practice entirely by 2030. Forty two countries – including both Senegal and its banana-shaped neighbor, The Gambia, have now partially or totally banned the practice.

But in countries where FGM is also widely practiced, such vast international advocacy can backfire, by creating the uncomfortable implication that local culture is “wrong” and needs help from Westerners who know better. One study of Senegal’s 1999 law banning FGM, for instance, found that without local advocacy and buy-in, the threat of punishment alone did little to change people’s minds about cutting.

Instead, many activists say, the call to end FGM must come not just from lawmakers or international NGOs or UN resolutions.

It must come from inside. In other words, it must come from women like Mané.

Since she first stood up to her in-laws 33 years ago, Mané has told her own cutting story dozens of times, perhaps hundreds – in packed rooms and under baobab trees in remote southern Senegalese villages, on the radio to thousands of people she doesn’t know and at her own kitchen table, to her own daughters.

“When you are a victim yourself, then you have unique skill to talk about what’s happening,” she says.

And a unique moral authority, too.

After all, when a local woman – a woman people in the community have gossiped with in the local market or knelt beside in mosque – stands up and says she suffered, it’s much harder for those around her to claim that anti-FGM activism is simply an import of a finger-wagging West, says Mary Small, the acting executive director of GAMCOTRAP, The Gambia Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, an NGO founded in the 1980s to fight FGM.

“To do this you have to be part and parcel of that culture, to show that their experience is your experience too,” she says. “When people know you accept them, that you are not condemning them for how they live, they begin to listen.”

Often, that work is slow going. In Gambia, three-quarters of adult women have been cut, and in Casamance, where Mané works, figures from 2005 put the number at 69 percent.

But activists like Ms. Small and Mané are not dissuaded. They know that cultural values shift slowly – often imperceptibly at first. At the root of their work, they say, is trusting that the women they work with are those best equipped to decide what is right for them and their communities.

“If you tell women the truth about what is happening to them, they will listen,” says Small, who before becoming an activist worked as a nurse in the delivery wards of several Gambian hospitals, and saw firsthand the painful medical complications of FGM. When she explains them to women now, she says, she finds they are often relieved to finally understand the cause of symptoms they have experienced.

Many are often equally surprised, she says, to learn that there are no references to FGM in either Islamic or Christian religious texts (cutting is practiced by both groups in Senegal).

“They think it is a religious obligation for them,” she says.

Both Senegal and The Gambia have formally outlawed FGM – Senegal in 1999 and The Gambia in 2015. But activists say that resorting to the law is, at best, a last resort. Their goal, after all, isn’t to make families who practice FGM out to be monsters, but to help them decide freely to change their minds, Small says.

So far, indeed, there has been only one successful prosecution under the new Gambian law. GAMCOTRAP, meanwhile, has convinced more than 150 “cutters,” the women who traditionally perform FGM, to abandon the practice, and given them money to start new businesses. The group’s support comes from a diverse array of organizations, from Kuala Lumpur-based Musawah (which advocates “For Equality in the Muslim Family”) and the African Women’s Development Fund to UN Women and the European Union.

“Things are changing, but not because of the law,” says Jaha Dukureh, another Gambian anti-FGM activist.

Instead, says Mané, it’s happening because women are making it happen.

“In all the years I’ve been doing this, I haven’t seen any turning point, really,” she says. “But each day perhaps you change one person’s mind. And that’s a success. That’s one more girl who doesn’t suffer.”

Maguette Gueye and Saikou Jammeh contributed reporting. Ryan Lenora Brown's reporting in Senegal and The Gambia was supported by the International Reporting Project.

Why saving elephants might hinge on finding common ground

Conservationists are split over how best to save elephants from the ivory trade. Now the question is emerging: Is that division itself a part of the problem?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

There's a giant elephant in the wildlife conservation room, scientists say. Some elephant conservationists are calling for a total ban on ivory, while others argue that a regulated market would better protect the animals. Frustrated by nearly 30 years of debate, nearly two dozen scientists have banded together in a call to unite these two causes for good. The first step, the authors of a paper published last week in the journal Science say, is to recognize that the two sides share the same goal: halting the slaughter of elephants for their ivory. The debate is rooted in a fundamental clash of perspectives on the best way to discourage undesirable behavior, through blanket prohibition or through controlled regulation. It's a theme that has surfaced repeatedly in conversations around controlling the abuse of alcohol, gambling, and smoking. Despite this impasse, the paper's authors say they are confident that common ground can be found with a little work and a willingness to compromise.

Why saving elephants might hinge on finding common ground

Imagine that an elephant approaches a village inhabited by blind men. Having never encountered such a creature, each approaches with arms outstretched eager to feel what they cannot see.

One man, touching a leg, declares the beast thick and strong like a tree trunk. Another, after encountering the trunk, describes the animal as squirmy like a snake. A third, after feeling the tip of a tusk, notes it is sharp like a spear. Eventually, a sighted man arrives and informs the men that they are all partly right but that they are also all wrong, a product of perceptions formed in isolation.

This ancient Indian parable offers a valuable lesson for the challenge facing elephant conservationists today, says wildlife researcher Gao Yufang. For decades, two distinct camps of elephant advocates have butted heads over how best to protect elephants. Each group has been so focused on their unique perspective that they have become blind to the entirety of the issue – and the common ground they share.

“We are all limited by our own perspective,” says Mr. Gao, a PhD student at Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in New Haven, Conn. “People tend to see the same problem in very different ways.”

Elephant conservationists share a common goal to halt the slaughter of elephants for their ivory. But they diverge into two distinct approaches toward that mutual aim: some advocate for a total prohibition of ivory on moral grounds while others see practical value in overseeing a regulated market.

At the root of the debate lies a fundamental clash of perspectives on the best way to discourage undesirable behavior, through blanket prohibition or through controlled regulation. It's a theme that has surfaced repeatedly in conversations around controlling the abuse of alcohol, gambling, and smoking.

Little cooperation so far

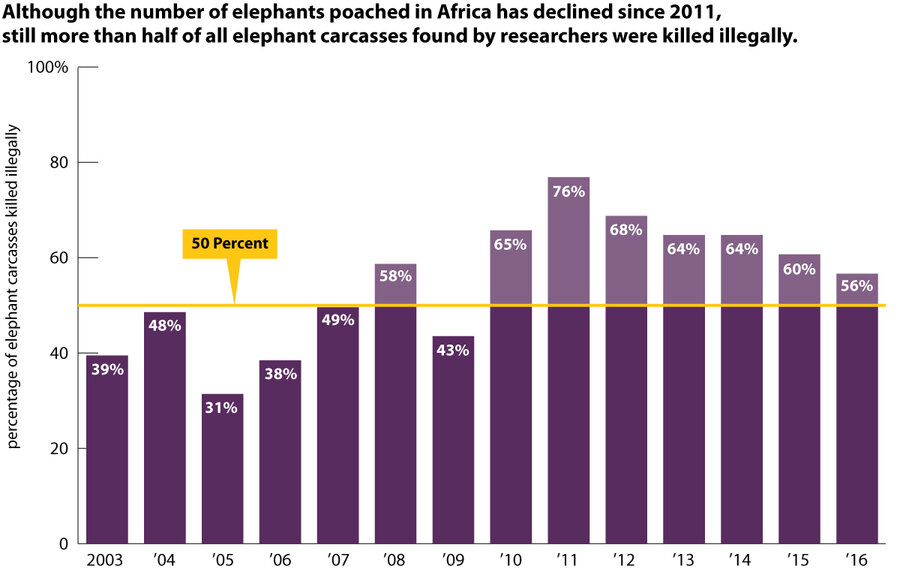

Elephant conservationists have seen some success in recent years. According to 2016 data, from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), poaching of African elephants has declined since its peak in 2011. However, poaching rates still remain higher than natural population growth, which means the overall population continues to decline. Advocates argue that is evidence a more concerted effort is needed to stem the tide.

Advocates for a regulated market assume there will always be a demand for ivory. They presume it best to satiate that demand with tusks harvested from elephants that have died of natural causes and invest the profits in conservation. Advocates of a total ivory ban counter that an absolute prohibition provides consumers and law enforcement officials a clear line of demarcation that eliminates any possible gray area.

There has been little cooperation between these two groups, as evidenced by the contradictory proposals that each have advanced over the years. Frustrated by nearly 30 years of debate, Gao and nearly two dozen scientists have banded together in a call to unite these two causes for good.

On Dec. 14, the researchers outlined a five-step process to break through the current impasse in the journal Science. The first step, they say, is to bring the two sides to discuss their goals for elephant conservation, with the aim of highlighting not just where their objectives diverge but also where there is common ground.

The truly difficult work needs to begin with a respectful discussion of “taboo trade-offs” between conflicting secular and sacred values – in other words, a search for common ground between one stakeholder’s sense of morality and another’s practicality. During this discussion, stakeholders should prepare to feel uncomfortable and to address “moral outrage,” says Robert Scholes, a co-author of the report and ecologist at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

“You can’t sweep the emotional aspect under the rug and say that doesn’t count,” says Professor Scholes. “You have to develop a process that considers people’s values, the evidence, and uses both to come to a workable outcome.”

Getting both sides to the table

Getting stakeholders to the table may be prove difficult, as some see these suggestions as more cycling through the same debate that has been hashed out for years. Even some among the original group of scientists who collaborated on the recent report had trouble reaching total consensus.

Some felt that the paper should advocate for one position over the other, but the majority of collaborators felt this would “raise the stakes, not calm them,” explains Scholes. This choice meant that a few original authors who fell on the extreme sides of the debate backed out of the paper during production because they felt that placing each side on equal footing created a false equivalency.

Still Scholes is confident that common ground can be found, because this approach has worked before.

In the mid-to-late 20th century conservationists were at a similar impasse over how to keep elephant herds in check. Advocates of controlled kills argued that culling was necessary to disrupt the cycle of spikes in population leading to shortages of food. Between 1967 and 1995, wildlife managers in South Africa’s Kruger National Park killed more than 14,500 elephants, a practiced that was strongly opposed by anti-culling advocates.

But the conversation changed when the two groups came together and realized that they had the same objective.

“It was by understanding that we weren’t fighting about elephants,” says Scholes, “we were fighting about the appropriate way to treat them in different circumstances.”

Now, instead of culling, the park’s wildlife managers rely on indirect methods such as reducing artificial water supplies that had allowed elephants to survive droughts and fostered unnatural population booms.

The solution to resolving the ivory impasse could be similarly simple, says Duan Biggs, lead author of the report and ecologist at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia.

“This is not rocket science,” says Professor Biggs. “We now need to have the political will to implement common sense so we can move forward, get past this deadlock, and focus on conserving elephants.”

CITES Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

When corporations come clean on climate effects

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A change may be going on among several of the world’s largest fossil fuel companies, names such as ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP. One of the biggest reasons: pressure from the companies’ shareholders. Climate Action 100+ is a shareholder action group that is asking corporations to make stronger commitments to meeting the 80 percent cut in carbon emissions proposed by the Paris agreement signed two years ago by nearly 200 nations (the United States has since indicated it will not abide by the agreement). Last week, international energy giant ExxonMobil said it will step up reporting to shareholders and the public about the impacts climate change will have on its business. Meanwhile, Shell has announced it will reduce its carbon emissions by 20 percent by 2035 and 50 percent by 2050. Vanguard, a huge mutual fund and big investor in ExxonMobil, is prodding the companies it invests in to make public the risks the companies face from climate change. Around the world, governments are shaping policies in an effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level that will not allow global temperatures to rise more than 2 degrees Celsius. But investor pressure is unique in that, principally, it asks only for clear, complete, and accurate data. Then shareholders can make informed decisions about where they want their capital to flow.

When corporations come clean on climate effects

Giant corporations often claim to be “green,” pointing to programs they’ve undertaken aimed at being environmentally conscious.

But sometimes these efforts don’t really amount to much. They can be no more than “greenwashing,” a public relations effort that doesn’t represent any fundamental shift in thinking.

But such a change may actually be going on among several of the world’s largest fossil fuel companies, names such as ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP. One of the biggest reasons: pressure from the companies’ shareholders.

Investors are asking corporations to make more transparent the effects climate change will have on their businesses, as well as explain what they are doing to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

While shareholder motives are certainly aimed at helping in the worldwide fight against global warming, they also represent a practical need to better understand a company’s prospects. If the burning of oil and gas is greatly curtailed as a result of the December 2015 international Paris climate agreement, for example, how might that affect the bottom line of a corporation whose chief source of revenue is extracting and selling carbon-emitting oil and gas?

Or, conversely, how is a company planning to take advantage of the business opportunities that emerge from a shift away from fossil fuels?

Climate Action 100+, for example, is a shareholder action group that is asking corporations to make stronger commitments to meeting the 80 percent cut in carbon emissions proposed by the Paris agreement signed two years ago by nearly 200 nations (the United States has since indicated it will not abide by the agreement). Some 225 investment groups who manage more than $26.3 trillion have signed on in support.

Last week, international energy giant ExxonMobil said it will step up its reporting to shareholders and the public about the impacts climate change will have on its business, including any expected increased risks.

The new policy follows a vote by ExxonMobil investors at the company’s annual meeting in May that called for a yearly assessment of the effects of climate change on the company.

The new position represents a sea change for ExxonMobil, which until the early 2000s had disputed the need to take action on climate change.

Last month, ExxonMobil, along with many other oil and gas companies, committed to stronger measures to reduce leaks of methane, an especially potent greenhouse gas, during its extraction operations. Meanwhile, Shell has announced it will reduce its carbon emissions by 20 percent by 2035 and 50 percent by 2050.

Vanguard, a huge mutual fund and big investor in ExxonMobil, is prodding all the companies it invests in to make public the risks the companies’ face from climate change.

Around the world national governments are shaping new policies in an effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level that will not allow global temperatures to rise more than 2 degrees Celsius. In the US, individual states and cities are pursuing lawsuits against companies that fail to deal responsibly with greenhouse gas emissions, which they contend harm the public.

But investor pressure is unique in that, principally, it asks only for clear, complete, and accurate data. Then shareholders can make informed decisions about where they want their capital to flow.

“Markets need the right information to seize the opportunities and mitigate the risks that are being created by the transition to a low carbon economy,” notes Bank of England Governor Mark Carney.

The world benefits as corporations provide that important information.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding God’s presence in ‘sacred solitude’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

Too many people today face a sense of isolation, especially at this time of year. But we don’t need to resign ourselves to inevitable loneliness. God, infinite Love, is right there for us to turn to, lifting the gloom of loneliness. As God’s creation, made in the very likeness of Love, we are never truly alone. God’s ever-present goodness is our greatest companion at Christmastime and at all times. When we open our hearts to this healing presence, loneliness is eased and evidence of needed human good comes to light as the love of divine Love becomes truly tangible, wherever we are.

Finding God’s presence in ‘sacred solitude’

I just break down as I look around

And the only things I see

Are emptiness and loneliness

And an unlit Christmas tree.

These poignant lyrics from a hit 1974 pop song resonate with too many people when aired anew in Britain each December (“Lonely This Christmas,” Mud). For instance, almost 4 million seniors in Britain see the TV as their main source of company, according to Age UK.

But TV is not the only available companion in such lonely homes. At any time we can seek and experience God’s presence through making space for “sacred solitude.”

That phrase was penned by 18th-century English poet Edward Young. And as theologian Paul Tillich has suggested, there is a distinction between loneliness and solitude. He wrote: “Language has created the word ‘loneliness’ to express the pain of being alone. And it has created the word ‘solitude’ to express the glory of being alone.” Seeking God in silent prayer opens our hearts to spiritual reassurance that can lift the gloom of loneliness with the healing realization that we’re never truly on our own, because God is omnipresent, ever present.

Admittedly, when we yearn for a touch, a hug, or familiar laughter, “sacred solitude” might sound rather abstract. Yet it offers us the un-aloneness of communion with the Divine, in which we can feel God’s all-encompassing love taking away any sense of being separated from good.

This love of Deity and its practical healing impact were most vividly experienced and expressed by the man whose birth is celebrated each Christmas, Christ Jesus. His healing love enabled many, whose illnesses left them isolated from others because of the customs of their day, to find a place back in their community. For instance, a hemorrhaging woman whose 12-year “issue of blood” would have ostracized her from family and society reached out to Jesus, and was immediately healed (see Mark 5:25-34). Her restoration to health removed the very reason for her isolation.

Such a turnaround points to an underlying reality in all such situations: that rather than being the isolated individuals we can sometimes seem to be, each of us is God’s creation, representing the fullness and the consciousness of God’s love.

If that’s truly what all men, women, and children represent, then any sense of lack, including the specific lack that is loneliness, is an impostor. It’s one aspect of a mistaken sense of ourselves as being material rather than spiritual. Contrastingly, an aspect of being spiritual – made in God’s likeness, as the Bible puts it – is having the constant companioning of the ever-present God. And when we glimpse what it means to us that this companionship is forever established and responsive, tangible evidence of human good comes to light.

I saw this happen for an older woman living alone and struggling to cope. I was one of several people helping to care for her, and one afternoon I felt inspired to read her a particular article based on Christian Science ideas. I can’t recall the theme of the piece, but I can still clearly remember how uplifted her thought seemed after I had read it. She felt God’s tender care. The room seemed to be filled with the presence of Love.

I felt the divine Love that is always with us had been revealed to her, and a practical solution to her need for loving company followed. The next day she received an unexpected visit from relatives she barely knew, who asked her to come and live with them. They wanted a companion for their loved dog because of their busy daily schedules. She was thrilled and took the opportunity to join this loving couple in their home. While there are many ways companionship can be felt, this perfectly met her need. I saw her a few months later and she was the picture of happiness.

God’s ever-present goodness is our greatest companion at Christmastime and at all times. When, in sacred solitude, we open our hearts to this healing presence, loneliness is eased as the love of divine Love becomes truly tangible, wherever we are.

Adapted from an editorial in the Dec. 11, 2017, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Season of light

A look ahead

Thank you for spending some time with us today. Tomorrow, we'll be looking at the train derailment in Washington State. The delayed implementation of long-called-for safety technology shows how differently the US approaches rail and air safety. Please join us again.