- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for December 19, 2017

Yes, we’re watching Congress vote on the tax reform bill today. But we’ve also got one eye on a selfless 8-year-old boy.

A few weeks ago, Jayden Perez decided the children of hurricane-battered Puerto Rico needed his Christmas toys more than he did. Then, his mom posted a video on Facebook, in which Jayden asks: “Can you donate one toy, from the bottom of my heart and the bottom of your heart?"

Jayden’s generosity struck a chord: More than 1,000 toys were donated and $9,300 has been collected on a GoFundMe page. Jayden now plans to help distribute those toys on the island during Three Kings Day, when Latino children traditionally receive gifts.

But selflessness isn’t limited to this third-grader from New Jersey.

In Ohio, 9-year-old Mikah Frye made a similar choice. When he learned his grandmother planned to buy him an Xbox One game console, he said the $300 would be better spent on blankets for a local homeless shelter. You see, Mikah’s family had previously availed themselves of the Ashland Church Community Emergency Shelter Services. And Mikah took it a step further, adding a handwritten note with each blanket.

We probably shouldn’t be surprised that children are often the best examples of the Christmas spirit. In prophesying the coming of Christ Jesus, Isaiah wrote: “and a little child shall lead them.”

Now let's look at the five stories we've selected that include a look at the fairness of US tax cuts, security shifts in the Middle East, and compassion vs. the rule of law for foreigners.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

What does tax bill mean for middle class?

Our reporters are looking at the Republican tax plan by examining the principles of fairness (tax cut), and simplicity (tax reform) as well as an emerging perception gap among US voters about the benefits of this change.

-

Laurent Belsie Staff writer

With Congress on the verge of passing historic tax reform Tuesday, Americans will now have to figure out how the myriad changes will affect their tax bill next year. The good news: Almost all Americans will qualify for a tax cut. The not-so-good news: Those tax cuts will peter out over time, so that a decade from now, only businesses and the high-income earners will be paying less. Of course, the real impact on particular households is complicated. The measure includes many changes to deductions and other provisions. People who don’t itemize, such as Minnesota schoolteacher Jeff Vogel, may benefit from the near doubling of the standard deduction from $13,000 for joint filers to $24,000. Some 55 percent of Americans oppose the measure, a new CNN poll found. The actual arrival of lower taxes could begin to change some minds. Or not. “It’s going to help our taxes out quite a bit,” says Mr. Vogel, “but I would much rather see that money go toward lowering our national debt and helping improve programs.”

What does tax bill mean for middle class?

Here’s the paradox of the Republican tax plan: It promises to deliver tax cuts to most Americans, but that doesn’t mean Americans like it.

Partly that reflects the politics of a bill that’s been widely publicized as favoring business and the wealthy over average households.

The plan, which cleared Congress with a House vote Wednesday, is also controversial because of projections that tax cuts will add to federal deficits at a time when the government chronically fails to balance its books – even during good times. [Editor's note: A timing reference in this paragraph has been updated.]

But it may also be that this bill is simply so fresh off the drawing boards that many Americans have little idea how it will affect their own pocketbooks.

A new CNN poll, which found 55 percent of Americans opposing the bill compared with 33 percent in support, also found that almost twice as many people think it’ll make them worse off rather than better off personally.

In St. Cloud, Minn., middle-school teacher Jeff Vogel has crunched some of the numbers and sees a tax cut on the way. He reckons his family will benefit from a doubling of the standard deduction, since currently they rely on that rather than itemizing various deductions such as property taxes. And although the law will eliminate personal exemptions, the family stands to gain from the bill’s expanded child tax credit.

“It’s going to help our taxes out quite a bit,” he says of the tax bill, “but I would much rather see that money go towards lowering our national debt and helping improve programs.”

Many Americans, like Mr. Vogel, aren’t judging the bill so much by whether it helps their own finances in the near term, but by whether they believe it helps Americans have a stronger and fairer economy. While many believe tax cuts especially for business will make the American economy more competitive, many others worry about rising deficits and a growing rich-poor gap.

Alongside all that, though, are very real impacts on household finances, including decisions some taxpayers may want to make before the end of this calendar year.

“Most people should see at least somewhat of a tax cut,” says Mark Luscombe, principal federal tax expert at Wolters Kluwer accounting firm near Chicago.

A skewing in benefits

The GOP plan benefits all income groups, at least initially, and as that becomes better understood, it’s possible that public opinion could become more supportive of the measure. But what’s also true is this: The individual tax cuts aren’t permanent (they’ll expire after 2025 unless a future Congress renews them) and the measure’s biggest benefits flow to the richest Americans.

Also, whether you like the tax plan or not, it isn’t doing much to simplify the tax code, notwithstanding Republican pitches about allowing people to file their returns on postcards.

“The biggest change is probably the increase in the standard deduction,” which roughly doubles to $24,000 for a married couple filing jointly, Mr. Luscombe says. That means the already large majority of US tax filers who don’t itemize deductions will get even larger, he says.

“That's about the only simplification in the bill that I see…. A lot of the complications are really from tax breaks to help lower your taxes,” and are popular, Luscombe says. “It's sort of social engineering through the tax code to try to help [people with] housing or education or retirement or health care.”

Pretty much all those provisions remain in place, sometimes with alterations.

Modest cuts for many

But with complexity can come uncertainty. A driving impetus behind the bill has been Republicans’ longstanding goal of cutting corporate tax rates, to help America compete globally for jobs and investment. But to pass the bill without Democratic support, using their narrow Senate majority, Republicans put a priority on making those corporate changes permanent, while allowing individual rate cuts to expire after 2025.

Moreover, even when individual rates do go down next year, that doesn’t mean all will pay lower taxes.

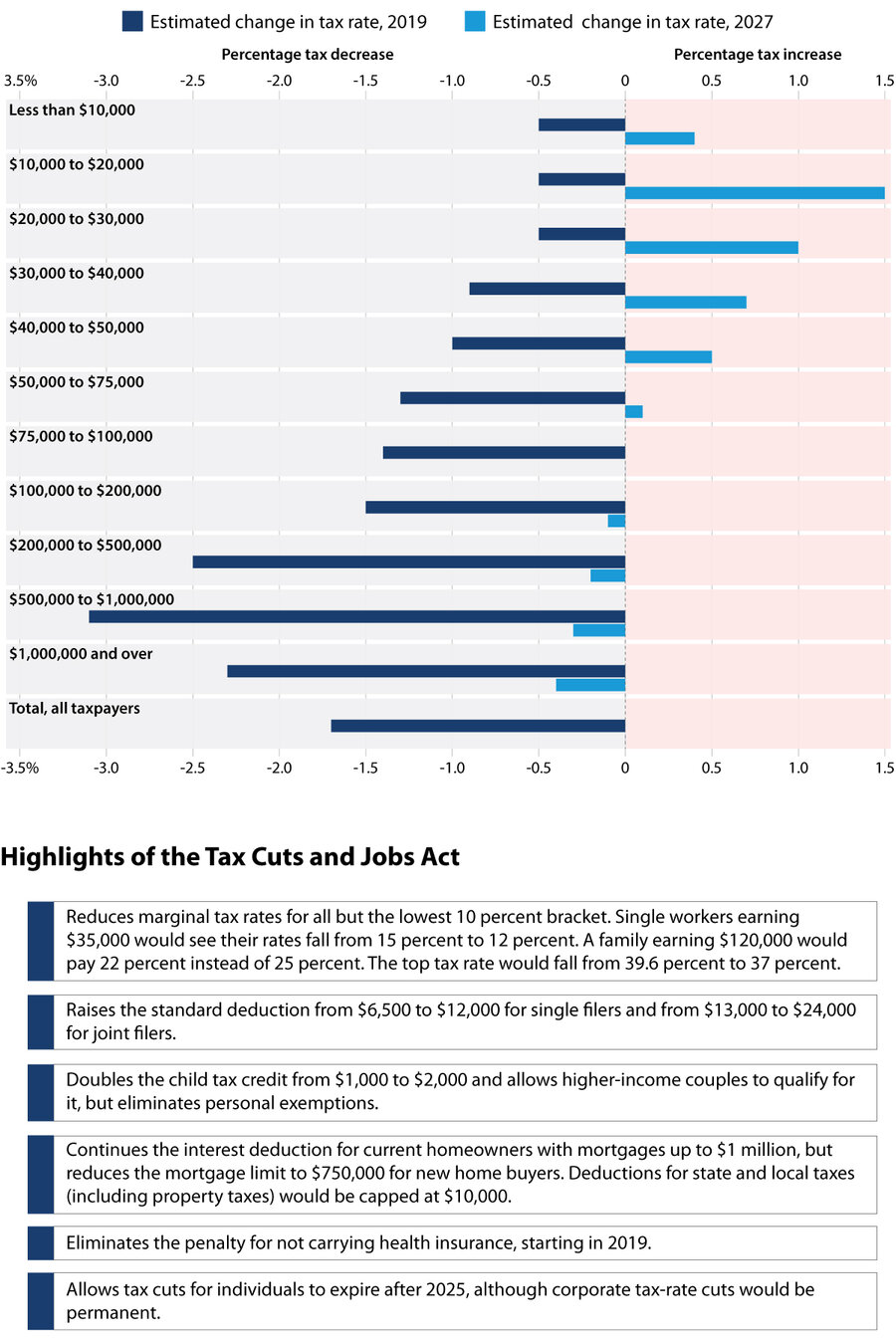

The tax bill gives rate cuts with one hand, while curbing many deductions with the other. So while tax cuts are broad, they aren’t particularly deep and they don’t reach everyone. A single person making, say, $28,000 a year would see an average drop of 0.5 percent per year – or about $140, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).

As one’s income goes up, so does the percentage change in taxes paid. A married couple making $90,000 a year would see an average drop of 1.4 percent, or $1,260; a professional making $300,000, a 2.5 percent drop ($7,500) and so on. The one exception are those who make at least $1 million. They would get a 2.3 percent drop, but that still results in huge tax savings averaging $23,000.

While many Republicans say that’s fair, given that higher income Americans currently pay the most in taxes, Democrats decry the plan as redistribution in the wrong direction at a time of widening inequality.

Here are key details of how the tax plan will affect individuals and families:

Rate cuts: The breadth of the tax cuts is most obvious in the new tax rates the plan will establish. Although the rate remains 10 percent for the first $9,525 in income – the next rate is 12 percent for income up to $38,700 (instead of the current 15 percent) and then 22 percent for up to $82,500 (instead of the current 25 percent), and so on. The top rate, for those earning $500,000 or more, drops to 37 percent from today’s 39.6 percent. The new lower rates also apply to couples filing jointly and other households.

Standard deduction: Under current tax law, single filers can exclude $6,500 from their income. Starting next year that jumps to $12,000, and to $24,000 for joint filers.

Local-tax deduction: Up to $10,000 in taxes paid to state and local government (property plus either income or sales taxes) will be deductible. The cap imposes a disproportionate hit on higher-earning residents of high-tax states.

Other deductions: A range of other deductions and credits are reduced or eliminated. The personal exemption is eliminated. The mortgage interest deduction remains, but is now capped on new loans up to $750,000, and interest on home equity loans no longer gets a break. Moving expenses, job-search expenses, and tax-preparation fees are no longer deductible. Credits for adoption and purchasing electric vehicles remain in place.

Family tax credits: The child tax credit is doubled to $2,000 per child, and it’s more available to both high earners (up to $400,000 in come) and low earners (up to $1,400 of the credit is refundable). The bill creates a $500 credit for non-child dependents such as aging parents.

Education: Republicans also backed off controversial moves on education, such as taxing graduate students’ tuition waivers. The bill preserves various college tax credits, plus deductions for up to $2,500 in interest on student loans, and up to $250 in teacher-bought school supplies. Tax-sheltered saving will now be allowed for private elementary and high school costs, not just for college, within so-called 529 plans

Obamacare: The “individual mandate,” a centerpiece of the 2010 Affordable Care Act, is effectively being repealed as of 2019. People will no longer face a possible tax penalty if they don’t have health insurance. Republicans say it’s a win for consumer choice, canceling an unpopular part of Obamacare without canceling its subsidies for individual insurance. Critics say that with reduced participation, premiums will soar and millions more Americans will become uninsured. Sen. Susan Collins (R) of Maine fought for GOP commitments to pass follow-on legislation aimed at buoying health-insurance markets as this change takes effect.

Phaseouts: Unlike the bill’s corporate tax cuts, which are permanent, the cuts for individuals are set to expire, so most Americans would be paying more taxes by 2027 than they do under the current law, according to the JCT. In part, that’s because one permanent change in the bill is to use a different measure of inflation (called a “chained” consumer price index) when adjusting the income scales for each tax bracket from year to year.

One exception to the overall phaseout of individual tax cuts: The upper-middle class and the wealthy appear on track to have their taxes remain lower after 2025.

“While the details of the TCJA [Tax Cuts and Jobs Act] have changed throughout the congressional debate, the basic story of the bill has remained the same,” writes Howard Gleckman of the Tax Policy Center in a blog post.

Plan now for 2018?

For the next eight years, however, an altered tax code is the new reality of life for everyone.

Kathy Pickering, executive director of The Tax Institute at H&R Block, says it’s time for taxpayers to consider getting some professional advice or help. (H&R Block is preparing online aids, like a calculator.)

Some decisions are already upon taxpayers. Ms. Pickering says that in the next week, some people may benefit from paying their property-tax bill early (so it’s deductible in the current calendar year), ahead of the coming $10,000 cap on state and local tax deductions.

People who like to accrue a tax refund each year, as a kind of forced savings plan, may want to keep watch on how their withholding changes under the new rates.

“This is a great time to do some W-4 planning,” Pickering says, referring to the paycheck changes that may happen in February, once government formulas are reset.

– Bailey Bischoff, on the Monitor staff in Boston, contributed reporting for this story

Joint Committee on Taxation

Share this article

Link copied.

Why rail safety lags, even as ridership soars

In this story, we look at why there’s inertia within the railroad industry when it comes to installing new safety systems. Sure, they’re expensive, but that’s not the sole source of resistance.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

A decade ago Congress mandated that railroads deploy an emergency braking system called positive train control, or PTC. The extended deadline for implementation: 2018. So when the ill-fated Amtrak 501 left Seattle for Portland, Ore., on its maiden run of a new high-speed link, it was headed for a section of tracks that still did not have PTC installed. As investigators focus on track conditions, questions are already arising over why the safety system wasn’t operational. The answers provided by the National Transportation Safety Board, railroad experts say, are likely to touch on Amtrak’s cultural struggles to enforce safety rules, including an age-old reluctance in the railroad business to make improvements without clear profit incentives. Preliminary reports suggest the derailment was similar to two recent incidents, including one in Chester, Pa. Just a month ago, completing the investigation into that derailment, NTSB chairman Robert Sumwalt wrote that “Amtrak’s safety culture is failing – and is primed to fail again – until and unless Amtrak changes the way it practices safety management.”

Why rail safety lags, even as ridership soars

Passengers on the Amtrak 501 leaving Seattle for Portland, Ore. were handed commemorative lanyards early Monday morning. After all, the new Cascades train was on its maiden run, part of a much-awaited expansion of commuter rail in the eco-conscious Pacific Northwest.

As the brand new 4,400-hp “Charger” locomotive got underway – and just after one passenger quipped, “Wow, we’re going fast” – witnesses said they heard “crumpling, crashing, and screaming” as the 13-car train derailed near Tacoma, Wash., killing three people and injuring more than 100.

The crash caught American commuter rail service – including railroad companies and a federally-funded manager, Amtrak – at a juncture of colliding trends: ridership is growing rapidly even as the industry grapples with inertia over safety problems. The result has been three major derailments in three years.

As investigators focus on track conditions and whether the 501 was going too fast into a curve – preliminary reports suggested the train was traveling at nearly 80 miles per hour in a 30 m.p.h. zone – questions are already arising over why a long-delayed emergency braking system called positive train control, or PTC, wasn’t operational a decade after Congress had mandated it.

The answers provided by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), railroad experts say, are likely to touch on Amtrak’s cultural struggles to enforce safety rules, including an age-old reluctance in the railroad business to make improvements without clear profit incentives.

“This was a new route around the Tacoma area, that was the first train over it.… The bridge looked rickety, and it’s on a curve – all of which raises questions about whether the engineer was exceeding 79 miles per hour while there was no system in place to enforce a lower speed limit,” says MIT-trained signaling expert Steven Ditmeyer of Alexandria, Va., who has expressed reservations about riding Amtrak. “I’m hoping it will be a wake-up call.”

The accident occurred after Amtrak registered a record year in 2016, during which it served 31.2 million riders. Ridership has grown steadily, especially on mid-range trips and commuter runs like the Cascade in the Pacific Northwest and the Downeaster in New England, both of which have seen double-digit percentage growth year-to-year.

The $181-million Cascades expansion was a bid to build ridership by increasing service and cutting 10 minutes off the Seattle-to-Portland run. That meant business travelers who have been used to disembarking at lunchtime could instead be in town for a 10 o’clock meeting.

Yet there were warning signs. Don Anderson, the mayor of Lakewood, Wash., warned on Dec. 4 that high-speed trains along the new route would make it “virtually inevitable that someone is going to get killed” without first making more improvements to signage and crossing grades.

And there appeared to be immediate similarities to crashes in 2015 and 2016 in which investigators cited operator error and a lax safety culture as contributing to deadly derailments outside Philadelphia and in Chester, Pa. In both cases, the NTSB found, a fully operable PTC system could have avoided the deadly destruction.

Completing the Chester derailment probe on Nov. 16, NTSB chairman Robert Sumwalt wrote that “Amtrak’s safety culture is failing – and is primed to fail again – until and unless Amtrak changes the way it practices safety management.”

Amtrak insists it is in the process of implementing 13 major new safety recommendations. What is more, the new Cascades train was fully equipped with PTC. The tracks, however, which are owned by Sound Transit, are not scheduled to receive the improvements until the second quarter of 2018 – several months after the inauguration of the new service.

A Union Pacific Railroad veteran, Jeff Young, recently told the American Association of Railroads that such delays are entirely due to the sheer complexity of building a from-scratch geo-mapping system of wayside signals across 60,000 miles of track. Some 2,400 engineers are at work on the project, he said, noting that “it is like creating an entirely new air traffic control system.”

Yet the $10 billion price tag for installing PTC has also challenged the bottom line-focused rail industry, which historically requires an “economic case” for improvements, as Bob Tuzik, a journalist who covers the railroad industry, wrote recently in “Interface: The Journal of Wheel/Rail Interaction.”

“One problem was that capacity improvements and running time improvements did not come about, but additional costs were incurred,” says Mr. Ditmeyer.

But tying the deeper issue of Amtrak’s safety culture to the Tacoma crash “is in the apples and oranges world,” argues University of Delaware railway expert Allan Zarembski, author of “The Art and Science of Rail Grinding.”

“The railroads are working on PTC, and it wasn’t implemented [on the new Cascades line], but that is not a surprise” given that Congress saw fit to extend the implementation deadline to 2018, he says.

“Whether the railroads agree or disagree with PTC implementation, they are required by law to have it implemented, and they are working aggressively to do that,” he adds. “It’s not something you can turn around and say, ‘Let’s do it today.’ It is very complex, expensive, difficult, and takes time.”

Before he came over to rail travel from Delta Air Lines, new Amtrak CEO Richard Anderson received an award from air traffic control leadership for his focus on the technical aspects of getting airplanes from point A to point B on time, and safely. That focus included pushing “next gen” air traffic control systems – which are in many ways similar to PTC.

In that way, Mr. Anderson may be primed to understand “the subtleties of this command and control, this train control,” says Ditmeyer.

“I’m right now personally looking to [Anderson] to take a leadership role on safety,” he says, “because at Delta he understood that [next-generation signaling] affected the efficiency of the total operation, whereas most other railroad CEOs view the signal people as problems, because they are the guys that stop the trains.”

How the Mideast's new superpower is expanding its reach

On Tuesday, Iran-backed rebels in Yemen fired a ballistic missile at the Saudi Arabian city of Riyadh, underscoring the tensions between Shiite and Sunni Muslims. Our next story illustrates the seismic shift in the balance of power in the Middle East, as Iran’s political, religious, and military influence grows, raising new questions about security.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Iran has achieved milestones of leverage and influence that rival any regional power in the past half-century. Until now, the Shiite Islamic Republic had met with only limited success trying to expand its influence across the mostly Sunni Islamic world. But today – on the back of years of Iranian military intervention to fight Islamic State and bolster its allies abroad, years of diminishing US leadership, and repeatedly outsmarting and outmuscling its chief regional rival, Sunni Saudi Arabia – Iran has emerged as the dominant power in the region. While there are limits to how far it can extend its authority, Tehran’s rapid rise poses new challenges to the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia as it undermines their previous dominance. Iraq and Afghanistan still pose tests. But “in historical terms,” says Mideast scholar Fawaz Gerges, “Iran has never had such a powerful position.” The question now: How far can Tehran extend its reach?

How the Mideast's new superpower is expanding its reach

With opulent furnishings and the finest cut-crystal water glasses in Baghdad, the new offices of the Iranian-backed Shiite militia exude money and power – exactly as they are meant to. At one end of the meeting room is a set built for TV interviews, with gilded chairs and an official-looking backdrop of Iraqi and militia flags, lit by an ornate glass chandelier.

A large portrait of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, hangs unapologetically in the next room, signaling that Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba is one of 44 Shiite militias – out of 66 active on Iraq’s front lines – that are loyal to Iran’s leadership.

An article of faith – universally accepted in Baghdad – is that Iran’s immediate intervention in June 2014 stopped the swift advance of Islamic State (ISIS) and “saved” the Iraqi capital, while the United States waffled and delayed responding for months, abandoning Iraq during its hour of need.

“If there were no Iranian weapons, then ISIS would be sitting on this couch,” says Hashem al-Mousawi, a spokesman for Nujaba, gesturing toward an overstuffed sofa as an aide serves chewy nougats from Iran.

“Our victory over ISIS is a victory for all humanity,” says Mr. Mousawi.

And also a victory for Iran, which has emerged from the anti-ISIS battlefields in Iraq, Syria, and beyond as an unrivaled regional superpower with more hard- and soft-power capacity to shape events in the Middle East than it has ever before experienced.

Until now, Shiite Iran had met with only limited success trying to expand its influence across the mostly Sunni Islamic world, despite the call decades ago to “export the revolution” by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

But today – on the back of years of Iranian military intervention to fight ISIS and bolster its allies abroad, years of diminishing US leadership, and repeatedly outsmarting and outmuscling its chief regional rival, Sunni Saudi Arabia – Iran has emerged as the dominant power in the region.

One narrative of the modern Middle East is of potentates trying to stamp their imprint across these often volatile states. From Egypt’s Pan-Arabist Gamal Abdel Nasser, to Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, to the theocrats in Tehran today, the region has served as the world’s premier crucible for rulers to forge geopolitical hegemony, often with failed results. This is to say nothing of the intrusive meddling of the US, Russia, and other outside powers over the decades.

But now Iran has achieved milestones of leverage and influence that rival any regional power in the past half-century. While there are limits to how far it can extend its authority, Tehran’s rapid rise poses new challenges to the US, Israel, and Saudi Arabia as it undermines their previous dominance. In a region already reeling from multiple wars, the residue of the Arab Spring uprisings, and a deepening Sunni-Shiite divide, the fundamental question is this: How far can Tehran extend its reach?

Ironically, the first steps of Iran’s ascendancy came as a result of American actions. US forces ousted the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001, and toppled Iraqi dictator Saddam in 2003 – both strategic enemies on Iran’s flanks. But it has been Iran’s own moves since 2011, in combination with the stepped-up dedication of its allies – especially Russia – and lack of devotion of its enemies, that have resulted in Iran’s new regional status.

Helping to defeat ISIS was a particularly exultant moment for the theocratic state. Iran has long accused the US of creating ISIS in the first place – citing Donald Trump’s frequent allegations on the campaign trail that President Barack Obama was the “founder” of the terrorist organization.

Declaring victory over ISIS in late November, Mr. Khamenei called it a “divine triumph” of the Iranian-led “axis of resistance.” Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, decreed Oct. 23: “Without Iran ... no fateful step can be taken in Iraq, Syria, North Africa, and the Persian Gulf.”

No doubt the US-led coalition and its more than 25,000 airstrikes contributed hugely to crushing ISIS and forcing it out of Iraq and Syria, as have the 3,000 American military advisers helping to rebuild Iraq’s armed forces. And no doubt Russian air power has been crucial to the survival of Iran’s beleaguered ally, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

But Iran has dramatically reshaped regional power structures in its favor through a pattern of pragmatic and often risky moves. Many revolve around creating and marshaling proxy, mostly Shiite, forces from as far away as Pakistan to fight on its foreign battlefields.

This gives it an edge over rivals such as Saudi Arabia, which has flailed in its attempts to push back against Tehran’s growing influence. Saudi Arabia’s young Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has called Khamenei “the new Hitler of the Middle East,” but the kingdom has been unable to slow Iran’s rise.

In its latest counterattack, for example, Saudi Arabia orchestrated the abrupt resignation in early November of Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, its most important Sunni political bulwark against the power of Shiite Hezbollah – and its patron, Iran – in a delicate coalition government.

Mr. Hariri, in his departure speech reportedly written by Saudi hands, said, “Wherever Iran settles, it sows discord, devastation and destruction, proven by its interference in the internal affairs of Arab countries.” Iran’s hands “will be cut off.” Instead, Hariri returned to Beirut a couple of weeks later, greeted the Iranian ambassador among well-wishers, and suspended his resignation.

Another example is Yemen, where Saudi Arabia has waged a 2-1/2-year war disastrous for civilians – with critical US military support – ostensibly to “roll back” Iranian-affiliated Houthi rebels. So far the results are an estimated 10,000 dead, hospitals and historical districts turned into rubble, and a Saudi blockade that exacerbates disease and mass starvation in one of the poorest nations on earth.

Israel also sees the threat from pro-Iranian forces gaining strength along its borders. Lebanese Hezbollah, created by Iran during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, has served as a model for Iran’s newer proxy forces and has grown battle-hardened in the Syrian civil war.

“In historical terms, Iran has never had such a powerful position,” says Fawaz Gerges, a Mideast scholar at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

“Iran made a conscious decision to invest both blood and treasure, particularly in Syria, and the odds were against Iranian influence,” adds Mr. Gerges, author of “ISIS: A History.” “Everyone, including myself, thought that Iran had made the wrong choices, that Iran would lose and ... was trying to shore up a dying regime. In fact, in terms of geostrategic influence, Iranian investment in Syria – billions of dollars and hundreds killed – is the spearhead that has allowed Iranian influence to spread.”

Iran hasn’t been immune from the violence engulfing much of the region. A double ISIS attack last June on Iran’s parliament and the Khomeini mausoleum in Tehran killed at least 17. It shocked the country and reinforced the official “fight them abroad, not at home” justification for Iran’s foreign adventures.

The country faces formidable risks in its outside military ventures, too: Every theater of war where Iran has been active has seen an uptick of Shiite versus Sunni sectarianism, which complicates Tehran’s ability to establish control. And there are risks of blowback against Arab Shiites, who may be seen by Sunnis and others as doing Iran’s bidding, further undermining Tehran’s influence.

Nevertheless, across the region Iran has improved its leverage using astute, asymmetrical means despite limited military resources. Three countries in particular – Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan – illustrate how Iran has expanded its power and highlight some of the risks it faces with its newfound clout.

In Syria, Iran has been key to achieving what Mr. Obama said years ago was not possible: the survival of the Assad regime, and a military “victory” over both ISIS and anti-Assad rebel forces once backed by the US, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Jordan.

Aside from sending hundreds of its own advisers to Syria, Iran helped persuade Hezbollah to fight in the country soon after an Arab Spring uprising began in 2011. Tehran deployed Shiite units from Iraq, raised a pro-Assad militia, and later recruited Afghans and Pakistanis to fight in Syria as mercenaries. Maj. Gen. Qasim Soleimani, the vaunted commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards’ Qods Force, reportedly flew to Moscow in mid-2015 and persuaded the Kremlin to weigh in with air power, a crucial factor in helping tilt the balance of the war.

On the ground, the systematic deployment of mostly Shiite Afghans is emblematic of Iran’s tactics. The recruits often agree to fight out of a desire to work and shared religious values. A Monitor investigation found that Iran offered members of the Fatemioun Brigade, a unit made up of several thousand Afghan migrants, as much as $700 a month, plus Iranian citizenship, houses, and long-term family support and education, if they took up arms.

Other migrants are intimidated or coerced into joining. Videos of captured Afghan fighters show many living in rudimentary conditions, exhibiting limited military training, and unable to speak Arabic.

“Iran has become an unrivaled regional superpower using proxy communities and proxy fighters ... as effective tools to spread [its] influence far and wide,” says Gerges.

The price has been high, both for Iran and its mercenaries. More than 500 Revolutionary Guards have died fighting in Syria since 2012, including a number of generals, according to tabulations by Washington-based analyst Ali Alfoneh. Hezbollah has lost 1,200 fighters, and more than 800 Afghans have perished.

Iran’s image has taken a hit, too. It has been backing a Syrian regime accused of multiple war crimes, from the use of chemical weapons to indiscriminate dropping of barrel bombs on civilian targets. Overall, the conflict has left as many as 470,000 dead and displaced more than half of Syria’s prewar population of 22 million.

Iran’s use of proxy forces in Iraq stretches back to 1982. That was the year Tehran formed the Supreme Council of the Islamic Revolution in Iraq and its 10,000-strong Badr Brigade militia. These forces fought against Saddam during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, and took part in a failed Shiite uprising in Iraq in 1991. Today some of the most pro-Iran militias in Iraq trace their lineage to Tehran’s support for anti-Saddam groups.

As regimes changed, so did targets. Starting as early as 2004, Iran-backed Shiite militias battled US troops in Iraq. They inflicted heavy American casualties and introduced noxious weapons such as the “explosively formed penetrator” – a device that could blast a lethal slug of molten copper through a vehicle. But these forces faded after the US withdrawal in 2011.

Iraq’s Shiite militias were reinvigorated in mid-2014 with the advance of ISIS. Iraq’s top religious authority, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, issued a fatwa calling on all able-bodied men to take up arms as ISIS forces pushed perilously close to Baghdad.

Iran moved quickly to shore up Iraq’s crumbling forces and took advantage of the fatwa, analysts say, to expand a network of well-financed Shiite militias that now number an estimated 150,000 fighters. Iran also poured arms and hardware into Iraq – $10 billion worth in 2014 alone.

The controversial militias are widely seen as tools of influence by Iran, though they operate under the umbrella of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF, or hashd al-sha’abi), which Iraqi lawmakers last December voted to officially incorporate into Iraq’s security forces. Harboring similar religious motivations with Iran, the militias sometimes enter battle wearing pins and waving banners with images of Iranian ayatollahs and generals.

US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said in October that, with the anti-ISIS fight coming to a close, “Iranian militias that are in Iraq ... need to go home.” Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif responded with a tweet: “Exactly what country is it that Iraqis who rose up to defend their homes against ISIS return to?”

“There is not a single part of Iraq without Iran,” says Hisham al-Hashemi, a defense analyst in Baghdad. “You find Iran in every detail.”

Indeed, shops are stocked with Iranian goods, and several million Iranians partake in an annual pilgrimage to Shiite shrines. Though Iraqi lawmakers have banned the militias from playing an overt role in politics, 28 political parties affiliated with the militias are already registered for 2018 elections.

Iran reportedly helped orchestrate the removal of Finance Minister Hoshyar Zebari last fall because he was considered too close to the US. Mr. Hashemi notes that the Iranians are intimately involved in Iraq’s security, politics, and economy, not to mention exert indirect influence over more than 58 TV and radio outlets and newspapers.

“Iran wanted to make Iraq only one entity, only Shiites,” he says. “Who is controlling Iraq now? Only Shiites. It is a big victory.”

Nowhere is Iran’s influence more obvious than in the headquarters of Iraq’s most pro-Iran militias, such as the Nujaba. It is here, sipping water from crystalline glasses, that pains are taken to explain how the loyalty of Nujaba’s 10,000 fighters to Khamenei – as the embodiment of Iran’s system of velayat-e faqih, supreme religious rule – is not the same as loyalty to Iran.

Nujaba has its own satellite TV station, and its propaganda videos highlight its fight in Syria around Aleppo. Nujaba’s leader, cleric Akram Kaabi, has been feted in Tehran and – echoing Iran – vows to carry on the fight, post-ISIS, against Israel.

“We don’t belong to Iran,” says Mousawi, the Nujaba spokesman. “If you follow velayat-e faqih, it is not an illegal crime.”

He draws a comparison with Roman Catholics and Pope Francis, who is Argentine. “So are the people who follow the pope agents for Argentina?” asks Mousawi. “If you follow the pope and the Vatican, do the people of your country say you are a traitor, and follow the Vatican?”

Similar views are heard in the offices of the Iranian-backed Khorasani Brigade militia. This unit also fought against ISIS and in Syria, at Iran’s request. But its members consider themselves Iraqi nationalists, says Khudayer al-Amara, a ranking member of the brigade’s Islamic al-Taleea Party. “It’s not necessary for all members to follow velayat,” says Mr. Amara. “They are unified to defend Iraq [and] defend victims of injustice. They think, when they fight in Syria, it’s the same battle as in Iraq.”

“If you ask me, the revolution of Khomeini and Iran has succeeded by exporting its revolution,” adds Amara. “Hezbollah and its followers believe in that revolution.... You can say that we [Iraqi militias] look like Hezbollah now – but we are Iraqi.”

Still, there are limits to Iran’s influence in Iraq. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has welcomed Iranian support but chosen a firmly nationalist path that also embraces the US-led coalition. In mid-2015, Mr. Abadi rejected an offer for Iraq to join an Iran- and Russia-led “Coalition 2.0.”

“Iran saved us. They later sent us the invoice, but they saved us,” says an Iraqi analyst who has worked for the Defense Ministry in Baghdad. “They literally sent us an invoice for the weaponry, the bullets, and the ammo that they gave us to fight ISIS, [which] proved to people that Iran does not look out for Shiite interests. Iran looks out for Iranian interests, period.”

The Shiite militias also may get more credit for military triumphs than they deserve. When he visited Fallujah during the mid-2016 fight, for example, the defense analyst says he saw no sign of the militias. But afterward, “I saw nothing but hashd, and their posters, and their flags,” he says. “They’re good at PR. You’d think they liberated the place.”

Nor are the flags always welcome. “We need to keep in mind that there was an awful eight-year war fought with Iran,” says the defense analyst, and Iraqis “don’t forget.”

The US still plays a significant role in Iraq, too. It gave Baghdad $5.3 billion in foreign aid in 2016 alone and lost 4,500 US soldiers. The US ambassador meets with the Iraqi defense minister every week. Abadi’s official website is full of pictures of the Iraqi premier meeting senior Americans officials. Iranians are absent. Such high-level contact has some Iraqis asking if the Americans, not the Iranians, should back off.

“You cannot discount Iraqi nationalism, especially after literally thousands of people – militias, Iraqi Army, Interior Ministry – have laid their lives on the line for the country,” says the defense analyst. “People say, ‘You’ve got to look at what Iran is doing with Hezbollah, in Syria.’ No, Iran looks after No. 1. As America does. And we [Iraqis] do as well.”

Iran must tread carefully in Afghanistan, too. It supports the government of President Ashraf Ghani – but also has given calibrated support to the Taliban for at least a decade to help it attack US forces, and more recently to crush ISIS.

Afghan government forces hold little sway over their Wild West border with Iran, where ISIS first popped up in 2014. But the Taliban does – and has proved to be an ideal tool for Iran’s buffer policy.

“For stopping ISIS, the best alternative is the Taliban, so it is easy for Iran to support the Taliban,” says Daoud Naji, a leader of Afghanistan’s Shiite Hazara community in Kabul. Proof of the brutal result came to him with pictures of dead ISIS fighters from an eyewitness. “The Taliban hung them, ISIS people, out on trees for weeks, and no one was allowed to take them down,” says Mr. Naji. “When Iran hit them strongly, [the ISIS fighters] moved to the east.”

That narrative is borne out by a map used by Afghanistan’s intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security. It shows ISIS emerging at points along Iran’s border in 2014-15, and then shifting east toward Pakistan’s border. “It’s a smart policy, to be honest,” says a Western official in Kabul.

It also benefits the US, he says. In 2014, Taliban defectors started aligning themselves with ISIS. “Was it US Special Forces that nipped that in the bud? No, it was probably Iranian-backed Taliban.... They have succeeded in stamping out the presence of self-declared ISIS groups in any province that borders Iran,” says the Western official.

Tehran’s main interest is preventing ISIS from crossing into Iran. Last year, Iran’s hard-line Kayhan newspaper described how Afghan recruits were taken for 25 to 35 days to a “special training base.” An Afghan intelligence operator confirms the base is in Birjand, an Iranian city 75 miles from the Afghan border. Of those sent there, 75 percent would go on to fight in Syria, while the remainder were shipped back to Afghanistan to work with the Taliban or attempt to infiltrate ISIS.

“Their job is to stop ISIS at the border,” he says. “They infiltrate ISIS ... but work for Iran. This is a new strategy for them.”

Still, Iran’s presence in Afghanistan continues to anger Kabul. Afghan security forces have arrested 50 or 60 people working for Iran in the past year, and “we have a plan to arrest more and more,” says the source. “They are ... using Afghan people like weapons against ISIS.” Some of those arrested are Afghans with Iranian identity cards; others are Iranian intelligence agents, he claims.

For now, Iran’s proxy strategy, in Afghanistan and across the Middle East, is giving Tehran unprecedented influence. The question: Will that bring more power or only more problems?

Briefing: Temporary Protected Status

Trump administration reconsiders status of 300,000 immigrants

The US has a policy of opening its doors to neighbors in need. But what if those temporary houseguests don’t want to leave? This story is a briefing on how the Trump administration is managing this enduring tension between compassion and principle.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

When hurricane Mitch struck in 1998, much of Central America was ravaged – and many Central Americans headed north. The United States’ Temporary Protected Status program, called TPS, shields people from deportation if they can’t return home because of civil unrest, health crises, or natural disasters, like Mitch. It’s meant to be short-term. But protection for Hondurans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Salvadorans has been renewed so many times that today, hundreds of thousands have been in the US for decades. That’s poised to change. The Department of Homeland Security removed TPS protection for Nicaraguans and Haitians in November, giving them 14 and 18 months, respectively, to regularize their legal status or head home. Hondurans’ and Salvadorans’ statuses are under consideration. Some argue TPS was never meant to be a path to long-term, legal residency, and that returnees could even be a boon for their home countries. But others point to still-dire conditions, like the highest peacetime murder rates in the world, or slow rebuilding from the Haitian earthquake, and question why protections are being removed now.

Trump administration reconsiders status of 300,000 immigrants

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is determining the future residency of more than 300,000 Central Americans and Haitians who have been in the United States under the Temporary Protected Status program.

Q: What is TPS?

TPS is meant to provide short-term protection from deportation for people who can’t return to their home country because of natural disasters, civil unrest, or health crises. The protection is designed as a reprieve lasting between six and 18 months, and it includes permission to reside and work in the US. Many Central Americans first received TPS following hurricane Mitch, which ravaged the region in 1998. But protection for Hondurans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Salvadorans has been renewed so many times that hundreds of thousands have been in the US for decades.

In November, Nicaraguans and Haitians lost their protection. The protective status for Hondurans and Salvadorans is still under consideration.

Nicaraguans and Haitians have been given 14 and 18 months, respectively, to regularize their legal status in the US or return home.

As of October, other countries whose people can qualify for TPS include Nepal, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.

Q: Why is this happening now?

At the end of October, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson sent a letter to DHS arguing that conditions in Central America and Haiti no longer justify protection from deportation. It’s true that the situation in Central America following hurricane Mitch has improved. But there are other conditions that many argue still merit attention, including some of the highest murder rates in the world for countries not officially at war. Although Haiti’s last serious earthquake was in 2010, it’s been battered by hurricanes in the interim, and some 2.5 million Haitians are still in need of humanitarian support, the United Nations estimates.

The secretary of State’s assessment is required by law during the TPS review process. But some see Mr. Tillerson’s evaluation – and moves to do away with temporary protection for these groups – as politically fueled, and as part of a hard-line approach that President Trump has taken toward immigration.

Others argue that TPS was never meant to be as permanent as it’s become. Poverty, crime, and corruption may exist back home for the people who have lost permission to stay via TPS, but the program wasn’t designed to serve as a path to legal, long-term residency.

Q: Are home countries prepared for this kind of return?

The return of individuals who have spent long periods living, studying, and working in the US is often portrayed as a boon for their home countries. The argument is compelling: In struggling nations, US-educated nationals could help inspire change. But it overlooks critical factors, such as whether the home countries are prepared to tap into these skills, offer employment opportunities, and help in the emotional aspects of transitioning “home” after such a long absence.

Formal employment opportunities are scant in Haiti, Nicaragua, and the Northern Triangle, made up of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. An uptick in deportations from the US has inspired some governments to run pilot programs offering job training for returnees. But with the removal of US protection for 2,500 Nicaraguans and nearly 50,000 Haitians, the wave of potential returnees could go from a trickle to a landslide, something neither Nicaragua nor Haiti is prepared for.

Complicating matters further, many TPS recipients have partners or children who are US citizens. There are an estimated 275,000 US-born children linked to someone with TPS.

Q: How are Central American and Haitian governments responding to the potential end of TPS?

Earlier this fall, the Haitian ambassador to the US argued that a TPS extension was “a necessity” for Haiti. He wrote that the country is still struggling to recover from the 2010 earthquake, and those challenges have been compounded by a cholera outbreak and damage from last year’s hurricane Matthew.

There are also concerns about how the termination of protection could affect remittances sent to the weak economies back home, which depend on these injections of cash.

Q: Is TPS the only program on the chopping block?

Mr. Trump’s executive order from January on border security triggered the review of many programs seen as admitting immigrants outside the normal legal channels.

Earlier this year, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which has protected some 800,000 young adults who were brought as children to live in the US illegally, was ended. As early as March, some DACA recipients could be eligible for deportation if Congress doesn’t move on an immigration overhaul.

Trolls, ogres, and giant cats: How Iceland celebrates Christmas

Our reporter and photographer share a sampling of Icelandic Christmas traditions, including the roles of trolls and elves, which are a fanciful reflection of the seasonal darkness and unpredictable landscape. Icelanders counter the dark with light – and the “Christmas book flood.” Books are the prized gift, and Icelanders young and old embrace a world of new ideas while sitting by the hearth.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Iceland is a very dark place at Christmastime, as the winter solstice offers less than five hours of sunlight a day. And that very literal darkness manifests in Iceland’s Christmas traditions. This isn’t the twinkling wonderland of a German Christmas, nor home of a jolly Santa Claus. Here there are 13 troll-like Yule Lads who bring children gifts – or a raw potato when they are bad. Their mother, Gryla, is a horned ogress who puts naughty kids in a sack to eat later. The monstrous Yule Cat lurks outside homes, ready to eat anyone who hasn’t received new clothing items before Christmas. The grimness reflects a respect for a landscape that Icelanders know they can’t outmaneuver, says Terry Gunnell, head of the folklore department at the University of Iceland. That includes the 2010 eruption of one of the country's volcanoes and the recent rumblings of another, which had been dormant for centuries. “Here everyone is aware of these natural powers that are out there.”

Trolls, ogres, and giant cats: How Iceland celebrates Christmas

Dozens of red and white-wax candles flicker in the home of Auður Ösp, in a bright red dress, her Christmas best, as she seats 10 strangers around her dining room table.

There are old-fashioned Christmas cards hung across a string by Santa clips. The table is set with reindeer figurines and snow-dusted pine trees, as our tour group sits down to learn about the many Icelandic traditions at Christmas, called Jól in Icelandic.

But lest anyone be confused, this isn’t the twinkling wonderland of a German Christmas, nor are the Christmas characters anything like jolly Santa Claus, we are about to learn as the icy wind whips up outside.

Here there are 13 mischievous, if not downright creepy, Yule Lads descended from trolls who bring kids gifts – or a raw potato when they are bad, a practice we are assured is still commonplace. Their mother, Gryla, is a horned ogress who poses a double threat, putting naughty kids in a sack to eat later. The Yule Cat lurks outside homes, ready to eat anyone who hasn’t received new clothing items before Christmas.

Ms. Ösp receives wide-eyed stares from two Australian guests, ages 5 and 8, but this folklore does more than frighten wayward children. It speaks to the darkness, literal and figurative, that has shaped belief systems and traditions here and ultimately, the Icelandic temperament.

“Iceland doesn’t do sweet,” says Terry Gunnell, head of the folklore department at the University of Iceland. “Iceland does threats from various outside forces.”

Christmas traditions derive from Norse paganism, at the winter solstice when people, without electricity, were desperate to fend off darkness. That longing remains. Along with steaming outdoor thermal baths, it is candles that help Icelanders cope with less than five hours of sunlight a day, with flames glimmering in homes, cafés, workplaces, even the mayor of Reykjavik’s office.

That darkness has shaped the Icelandic sense of the supernatural, says Professor Gunnell, and today many hold superstitions about trolls or elves or “hidden people” that inhabit the hills around them. He says if you ask an Icelander if he or she believes in elves, most will reply "no." Yet in a survey Gunnell conducted with the university in 2006 and 2007, only 13 percent deny their existence completely.

He says it comes down to respect for a landscape that Icelanders know they can’t out-maneuver. There was the eruption of the volcano Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 that disrupted air travel across Europe and the new rumblings of Öræfajökull, dormant since its last eruption in 1727-28. “Here everyone is aware of these natural powers that are out there.”

This goes mainstream at Christmas time, in the shape of the Yule Lads who descend from the mountains the 13 days before Christmas, each named after their vice, such as Sausage Swiper and Bowl Licker. They’ve morphed into more benign creatures in this century, often dressing in red and seen more as pranksters, but still useful for parents in the month of December.

“We say, 'the [Yule Lads] have already left the mountain, you better go to sleep now,' ” says Olof Bjarnadottir, who teaches a course called “Being Icelandic” at the University of Iceland.

She opens her arms wide. “In summer we are all like this, the community goes outside. Then as the daylight lessens,” she says, spinning in a half circle in her chair and closing her arms until they are folded, “it’s just us, fewer and fewer people are invited. You minimize the circle when it’s Christmas.”

Back in Ösp’s dining room, the guests have never met one another before this evening. But that’s OK, because we are recreating all the traditions that precede Christmas in Iceland.

First up are the small gatherings, called Litlu-Jól, with groups of friends and associations, which Ösp describes on her blog, I heart Reykjavik, as an “Icelandic take on Scandinavian hygge with a Christmas twist.” (Hygge is a much-blogged about Danish word for coziness and conviviality – sometimes involving knitwear and, of course, candles.)

The meal starts with Christmas tea and bowls of homemade cookies, much to the children’s delight. Next up are open-faced sandwiches of raw herring and salmon, Danish recipes common in Christmas buffets that workplaces host and restaurants increasingly offer throughout the month. We are spared the fermented skate that Icelanders eat Dec. 23, the day of St. Thorlák, patron saint of Iceland. The main dish is the traditional Christmas meal of smoked lamb – not to everyone’s taste – and leaf bread, wafer-thin and decorated with intricate patterns.

Jól is at 6 p.m. Dec. 24. And Ösp assures us it is neither 5:45 p.m. nor 6:15 p.m. but 6 sharp, after five minutes of silence on Icelandic radio preceding the chiming of bells and Christmas mass. Her family would sit down and listen to it – as they will this year – even though she’s among 30 percent of Icelanders who don’t officially belong to the Lutheran Church of Iceland, having been married by a pagan priestess in her backyard.

Iceland is one of the most secular nations in the world, but there is no separation of church and state. It’s one of many paradoxes in Icelandic culture. “Icelandic people love to tell you that we are very progressive. … But we are also very, very traditional, and traditions are so important in December,” she says. “I always say Iceland is a country full of contradictions. Ice and fire, volcanoes and glaciers. Icelandic people are exactly the same.”

One of their dearest traditions is the “Christmas book flood.” While iPads and iPhones compete with the written word here too, Icelanders assure visitors that a book is still the most popular gift item, and they are devoured over Christmas holidays. Forget toy catalogues: It’s the “book flood” that kids await in the mail.

Melissa Bates, the mother of two from Australia, says Icelandic Christmas feels more traditional than back home. “Australia has copied America a lot, it’s very commercialized and losing that family feel,” she says. “It seems that here you still put the importance into what Christmas is all about.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A new deal for South Africa

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

With Nelson Mandela at its helm, in 1994 the African National Congress ended apartheid and white minority rule as the world looked on in awe at a remarkably peaceful transition of power. But the metamorphosis of the ANC from a revolutionary movement to an effective ruling political party has not gone smoothly. While the ANC has been able to close somewhat the gap between an impoverished black majority and a well-to-do white minority, a wide chasm of inequality in income and opportunity still exists. Jacob Zuma, president of South Africa for the past eight years, has embodied many of the shortcomings of his party – dogged by accusations of corruption and scandal. The choice of Cyril Ramaphosa Monday as the new party leader (and South African president-in-waiting) has renewed hopes that the ANC will heal itself. Many years ago Mr. Ramaphosa was Mr. Mandela’s first choice to succeed him. He is known more as a low-key negotiator than a firebrand leader. But in a speech last month he sounded like the reformer that the country needs. He spoke of the need for “an uncompromising rejection of corruption, patronage, cronyism and wastage.” He added: “To those with vested interests in ineffective governance, deliberate misgovernance, hidden deals, the concentration of economic control and unfair labour practices, we say: no more.”

A new deal for South Africa

The African National Congress flag consists of three colored bars: Black represents the people of South Africa, green the fertile land, and gold the abundant mineral wealth.

With Nelson Mandela at its helm, the ANC in 1994 ended apartheid and white minority rule as the world looked on in awe and gratitude at a remarkably peaceful transition of power.

But the metamorphosis of the ANC from a passionate revolutionary movement into an effective ruling political party has not gone smoothly. While the ANC has been able to close somewhat the gap between a vast undereducated and impoverished black majority and a well-to-do white minority, a wide chasm of inequality in income, employment, and opportunity still exists.

Jacob Zuma, ANC leader and president of South Africa for the past eight years, has embodied many of the shortcomings of his party. He has been dogged by accusations of corruption and scandal that have put into question whether the ANC leadership has lost sight of its lofty goals, becoming instead a party that enriches those at the top who use patronage jobs to keep and misuse their positions of power.

That’s why so much attention is being paid to the ANC party elections held Monday. The choice of Cyril Ramaphosa as the new party leader (and South African president-in-waiting) has renewed hopes that the ANC will heal itself.

In some ways Mr. Ramaphosa is an unlikely reformer. The longtime party member, who currently serves as deputy president to Mr. Zuma, has not been among Zuma’s leading critics.

Many years ago Ramaphosa had been Mr. Mandela’s first choice to succeed him as president. When rival factions blocked that move, Ramaphosa left politics, using his connections to become a wealthy businessman.

But reformers take heart from the fact that Zuma backed a different candidate, his former wife Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, to be his successor. That has left Ramaphosa free to set a new course.

Some party critics hope that Ramaphosa will ask Zuma to step down as president in the next few weeks, hastening the timetable for change. But if not, Ramaphosa will almost surely be elected president when Zuma’s term ends in 2019 (he is ineligible to run for reelection).

Ramaphosa is known more as a conciliator and low-key negotiator than a firebrand leader. But in a speech last month he sounded like the just the reformer the country seeks.

He spoke of the need for “an uncompromising rejection of corruption, patronage, cronyism and wastage” – part of what he pledged will be a New Deal for South Africa. He added: “To those with vested interests in ineffective governance, deliberate misgovernance, hidden deals, the concentration of economic control and unfair labour practices, we say: no more.”

But change won’t be possible, he said, “as long as key public institutions continue to be used for the criminal benefit of a few and public resources continue to be looted.”

He concluded: “We want every rand stolen from our people returned. We must search for this money in bank accounts throughout the world.”

Will this encouraging talk result in action? Will the black band on the ANC flag finally reap the benefits of its green and gold riches?

If so, the election of Ramaphosa someday may be seen as the greatest moment of progress for South Africa since the Mandela revolution itself.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Christmas is about receiving

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Linda Kohler

There are many ways to commemorate Christmas, and giving gifts has become one of the most popular traditions of the season. But as today’s contributor thought about the Gospels chronicling the birth of Christ Jesus, she noticed that there was a lot of receiving going on – the main characters in the Nativity story were each letting in something sacred, divine. We can all receive that kind of goodness in our lives. The ever-present Christ, God’s message of infinite love for all, comes to each one of us. We’re not responsible for creating it. We’re just required to be humbly open to it. As our hearts awaken to the truth of what we are as the very reflection of God, good – the truth that Jesus taught and that Christmas commemorates – we find ourselves more ready to recognize and accept the good God is imparting. This is our Christmas gift to receive with joy – anytime!

Christmas is about receiving

Yes, you read that right. There are many ways to commemorate Christmas, and giving gifts has become one of the most popular traditions of the season. But as I think about the nativity story chronicling the birth of Christ Jesus, it seems to me there was a lot of receiving going on. God was the giver, and every character in that simple story was engaged, probably more than most, in receiving: a message, direction, healing.

For instance, Mary received a visit from an angel, telling her she – a virgin – would have a son. She took in this news with amazing composure. She readily accepted this as God’s will for her, as unusual and even daunting as it may have seemed.

Shepherds received with joy the news that a savior had been born, and followed the star to the manger in Bethlehem. They came offering their adoration, which we might imagine Mary and Joseph received with a bit of wonder.

It seems like everyone in the story was being asked to accept the goodness of God, Spirit. This good was, in each case, simple and at the same time remarkable. It involved setting aside the ordinary, the mundane, and letting in something sacred, divine.

And isn’t that something we could all use more of in our lives? Qualities like stillness, hope, compassion, gratitude have their source in divine Love, and as we express these qualities, we’re living our authentically spiritual nature as God’s own spiritual creation. These gleams of divine goodness are evidence of the ever-present Christ, God’s message of infinite love for all. Author Mary Baker Eddy once described Christmas as “…the dawn of divine Love breaking upon the gloom of matter and evil with the glory of infinite being” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 262). Are we prepared to receive the Christ? What a glorious way to experience Christmas!

When we receive something, we’re not responsible for creating the gift ourselves. That role belongs to the giver. We’re just required to be open. To be humble enough to allow something to be done for us or given to us. Pride or cynicism would close that mental door of receptivity. Looking to “things” as the source of happiness or completeness would distract us from the value of the gift of God’s infinite goodness. But because we are inherently spiritual, made in the image and likeness of divine Spirit, we have a natural capacity to discern the reality of good. It’s how we’re made.

I’ve found that the Bible, and especially the teachings of Christ Jesus, help with this. For instance, Eddy once wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” referring to Jesus: “His senses drank in the spiritual evidence of health, holiness, and life;...” (p. 52). Jesus “drank in,” received, goodness. He understood that good from God is constant, and that we are all worthy to receive it.

And he showed us that we have constant opportunities to receive blessings if we open our hearts to the good God is offering us. As our hearts awaken to the truth of what we are as the very reflection of God – the truth that Jesus taught and that Christmas commemorates – we find ourselves more ready to recognize and accept the good God is imparting. We may be like Mary and immediately accept it. Or we may gradually grow to accept it. The thing to remember is simply that it’s there. The “dawn of divine Love” in our thought is our Christmas gift – to receive with joy during the holidays, and anytime!

A message of love

Festival of Lights

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about how southern Californians are helping their neighbors who lost everything in the recent fires get through the holidays.