- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for December 29, 2017

Year’s end is a time for looking back then boldly forward.

Often “the now” intrudes. A fatal fire in the Bronx Thursday night, reportedly started by a child playing with a stove, marked a detour from a long national trend toward residential fire safety. We'll go deeper on that story below.

Across the globe, in Mumbai, a fire at a rooftop restaurant also killed more than a dozen people.

Those are hard headlines, and there are more. Arctic air is wreaking havoc in the US Northeast and elsewhere, freezing sharks mid-swim. In the Indian capital, New Delhi, it’s air quality that’s the real crisis.

But some better trends stand out in a scan of this week’s quieter news. As it happens, India also produced some stories with encouraging topspin, and all in one narrow realm.

A village in Telangana is feeling the effects of its shift a decade ago to organic agriculture – including a decline in farmer suicides brought on by crop loss and debt. A Bhopal banker has created a no-fee produce brokerage that serves farmers (and consumers) in his region. A New Delhi doctor is going to court against those who feed children an unhealthy appetite for processed food – and pointing children at staples like lentils and rice. Finally, a new high-speed fiber optics grid will deliver all of that ripening knowledge, including to rural villages never before served.

Now to our five stories for today. First, an editor’s request: If your reading practice has been to scroll your Daily as an email (a fine way to ingest it), please also try popping open the enriched version on your mobile or laptop for the photos and full reads.

New years are for new practices, too!

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Despite tragic blaze, New York's fire fatalities are sharply down

Loss of life among the most vulnerable members of a broadly prosperous culture is hard to accept. The context that helps: Fatal fires are becoming much less common. But the complications around “clustering” still need addressing.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

The deadly fire that tore through a Bronx apartment building Thursday night is reminiscent of a time that New York firefighters had hoped to put behind them. The city has come a long way from the “Bronx is burning” stereotype of the 1970s. Back then, New York City saw 250 to 300 fatalities every year from fires. In 2016, there were only 48 civilian deaths – the lowest number in more than 100 years of record keeping. Experts attribute the improvement to better building codes, along with a combination of initiatives the Fire Department has undertaken, including increasing fire inspections around the city, improving response times to emergencies, and providing residents with smoke alarms and more fire-prevention education. The challenge now is less about codes and more about culture. “Fires are very much a function of income,” says one fire-safety expert. “What you find is that lower-income families tend to have more fires, largely because they tend to have stuff that’s older, stuff that’s been worn out and more likely to fail and propagate the fire.”

Despite tragic blaze, New York's fire fatalities are sharply down

Just one year ago, New York City officials were celebrating the lowest number of fire fatalities the city had ever seen in over 100 years.

On Thursday, however, on one of the coldest and windiest nights of the year, a deadly blaze swept through a Bronx apartment building, killing at least 12 people, including a one-year-old and his mother.

It was the largest number of fatalities in a single fire in New York since 1990, when 87 people perished in an arson attack on a Bronx social club – less than a mile from the scene of last night’s deadly fire.

“We’re here at the scene of an unspeakable tragedy in the middle of the holiday season, a time when families are together,” said New York Mayor Bill de Blasio (D) at a press conference Thursday evening, with temperatures in the teens. “Here in the Bronx, there are families that have been torn apart.”

But while Mayor de Blasio’s words of anguish stand in stark contrast to his words of celebration just one year ago, the city has come a long way from the “Bronx is burning” stereotypes of the 1970s.

Back then, New York’s five boroughs saw upwards of 250 to 300 fatalities every year from fires. By 2000, however, the city experienced half that number. There hasn’t been more than 100 fire fatalities in one year since 2006.

In 2016, there were only 48 civilian deaths from fires, the Fire Department of New York reported – the lowest number in over 100 years of record keeping. And over the past few years, the Bronx has generally seen fewer fatalities than other boroughs. In 2015, there were 59 fatalities throughout the city, but only 3 were in the Bronx.

"Multiple fatality fires are very rare nowadays,” says Marcelo Hirschler, a fire safety expert with GBH International, a fire safety consulting firm in Mill Valley, Calif. “[And] to a large extent, fires are killing fewer people one at a time.”

Part of the reason for this, says Mr. Hirschler and other fire experts, is that the United States has become a world leader in building codes – especially when it comes to taller buildings.

New York City officials, too, point to a combination of initiatives the Fire Department has undertaken over the past decade, including increasing fire inspections around the city, improving response times to emergencies, and providing residents with smoke alarms and more fire-prevention education.

Similar efforts around the country, experts say, has helped make the risk of dying in a fire drop 21.6 percent over the past decade, according to the U.S. Fire Administration.

But where the US struggles, Hirschler says, is less about codes and more about culture. “Fires are very much a function of income, and what you find is that lower-income families tend to have more fires, largely because they tend to have stuff that’s older, stuff that’s been worn out and more likely to fail and propagate the fire.”

New York City officials said Friday that a 3-year-old boy had been playing with the kitchen stove, which then started a small fire. As it grew, the child’s mother took the boy and his 2-year-old sibling and fled the apartment, CNN reported.

But she left the door open, fire officials said, a fatal mistake that caused the fire to burst into the rest of the floor, where the stairway acted “like a chimney,” sending smoke and flames to the rest of the building.

"Close the door, close the door, close the door," said FDNY Commissioner Daniel Nigro on Friday, emphasizing one of his department's frequent messages to residents trying to escape a fire, especially in a city in which most people live stacked on top of each other in multi-unit apartment buildings.

The building also had open violations for broken smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, city officials said, though de Blasio said the violations did not appear to contribute to the fire’s fatalities.

“When it comes to public policy on clustering people – whether you are a migrant camp in Beijing, whether you are a refugee camp in Jordan, whether you’re living in Port-au-Prince, or whether you’re living in Rio de Janeiro – it all comes down to the ability of, how do you separate people, so if one person has a problem you don’t lose the whole community?” says Robert Schroeder, a former firefighter who now heads a fire and explosion analysis firm in Minneapolis.

“If people are living in common places, like that apartment complex in the Bronx, [you need to design it] so if you have a fire in one unit, you don’t take out the whole building,” he says.

Fire alarms and smoke detectors have played a huge role in reducing fire deaths in the US, Dr. Schroeder says, but he also points out that there is an unrecognized and important element in the construction and renovation of buildings: gypsum wall board.

“It is actually endothermic,” he says. “Sheet rock contains 50 percent by weight and 20 percent by volume chemically bound water, so as you get a fire in a room, the sheet rock is actually throttling it down.”

It’s another reason residents should make sure all doors are closed after fleeing a fire, experts say.

The tragedy and loss of life in the Bronx on Thursday was “without question historic in its magnitude,” Commissioner Nigro said. “Our hearts go out to every family that lost a loved one here and everyone that’s fighting for their lives.”

The mayor, too, urged New Yorkers to keep the victims in their thoughts during the rest of the holidays. “This evening, hold your families close and keep these families here in the Bronx in your prayers,” de Blasio said.

Share this article

Link copied.

Innovation: 18 leaps to watch for in 2018

There’s technology that delights us and eases life around the edges. And then there’s technology that transforms. The Netherlands now outproduces all other nations on a per-square-mile basis, not just in tulips but also in some key food crops. That’s precision farming, digital and data-based. And it’s just one tech trend to watch.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 16 Min. )

The coming year will probably bring many surprises, but we can be confident in making at least one prediction: Technology will advance. And despite headlines warning of malevolent artificial intelligences, unscrupulous hackers, and greedy tech billionaires, many of these improvements will actually help make the world a safer, saner, and more prosperous place for the majority of us. Fueled by advances in electronics, software, and materials science as well as by the imaginativeness of researchers and inventors, a number of new technologies promise to help curb global warming and biodiversity loss, ease commutes, and stretch the planet's natural resources to feed and house the nearly 10 billion people who are expected to be sharing it by 2050. From rooftop fans that pull carbon dioxide from the air to 3-D printed homes to radical concepts in transportation, here are 18 ideas to look out for in 2018.

Innovation: 18 leaps to watch for in 2018

Designer solar

If you want solar panels, you don’t necessarily need to make your home look as if it’s covered with cereal boxes. Many companies are developing technology that lets homeowners integrate photovoltaic cells right into their houses’ existing architecture.

Tesla, the electric car innovator, makes solar tiles that look like ordinary roof shingles. The company has installed them on about a dozen homes so far, including that of the company’s founder, Elon Musk, and orders for more are already sold out well into 2018.

Meanwhile, a team of researchers at Michigan State University in East Lansing has developed transparent solar cells that capture invisible wavelengths of sunlight, meaning that they can double as windows. Scientists estimate that 75 billion square feet of windows exist in the United States, and that replacing them all with transparent solar panels could supply 40 percent of the nation’s energy.

And once your roof and windows are generating electricity, you might as well plug the rest of your house into the sun as well. A team of Australian researchers has developed solar-powered paint. It works by soaking up water vapor from the air and then using the energy from sunlight to split the water into oxygen and hydrogen gas. The collected hydrogen is used in fuel cells.

These technologies will take time to become affordable – the solar paint, for instance, isn’t expected to be commercially viable for a few years – but they represent the rise of solar as an increasingly practical energy source.

No hands on deck

Fully autonomous cars for the masses may still be years away, but unmanned transport may show up sooner in a different venue – on the wide-open seas.

In Norway, Yara International plans to transport fertilizer via an electric-powered ship that would travel along the Trondheim Fjord. The ships are scheduled to be piloted by remote control in 2019 and to go fully autonomous the following year. This year in Copenhagen, Denmark, Rolls-Royce demonstrated an autonomous tugboat. And a Boston-based start-up, Sea Machines Robotics, is working on a container ship to move goods across the North Atlantic without a human at the helm.

Proponents say that autonomous ships offer several advantages over crewed ones: They are less prone to error, less vulnerable to piracy, and can be designed with larger carrying capacity. They could also offer a solution to the growing shortage of skilled maritime workers.

The ships will still need some human guidance: Workers at operations centers on land will monitor the vessels’ maritime environments and take control of the ships remotely when needed. But the automation of shipping will mean workers will no longer have to spend weeks or months away from home. Instead, the sailor’s life will be ... just another cubicle job.

I, caregiver

Seniors represent one of the fastest-growing demographic groups in the developed world, but demand for professional caregivers far outstrips supply. How can societies fill the gap? Consider a little silicon.

Traditionally, robots have been tasked with performing work that is dirty, dangerous, and dull. But a new generation of robots is emerging to meet a complex psychological need: companionship.

Social robots, such as the Israeli-built ElliQ, help owners schedule appointments and stay in touch with friends and family by simplifying communication technology. The robot, which looks like a cross between a desk lamp and a bobblehead doll, sits on a stand next to an Android tablet. Billing itself as an “emotionally intelligent robotic companion,” ElliQ helps connect seniors with social media, video chats, and Facebook Messenger. It can learn its owner’s preferences, offering suggestions for books, entertainment, and outdoor activities. The device is set to become commercially available in 2018.

Social robots already on the market include Jibo ($899), a household companion with advanced facial-

recognition technology, which can identify and address people by name. Paro ($5,000), a therapeutic robot modeled after a baby harp seal (pictured), is widely used in Japan as a relaxation aid for older people. Paro’s sensors detect light, sound, touch, and posture.

Companion robots need not be expensive: Hasbro’s “Joy for All” robotic cats and dogs, which purr, meow, bark, and wag their tails in response to sound and touch, retail for about $100. They’re used in nursing homes around the United States.

Looks do matter

Facial-recognition systems have been used for everything from stadium security to unlocking a phone. But humans, it turns out, aren’t the only ones with machine-readable mugs: US researchers have developed a system that can reliably distinguish the faces of red-bellied lemurs – the furry primates with eyes like headlights that are among the world’s most endangered mammals.

The system, called LemurFaceID, could enhance wildlife conservation efforts by allowing biologists to identify and track the animals, found only in the wilds of Madagascar, without having to sedate and tag them. The technology works by identifying the fur on the lemur’s face, and its inventors suspect it could be used to monitor other species with distinct facial fur patterns, such as red pandas, raccoons, and sloths.

Already, scientists have used facial recognition with fish. In 2016, the Nature Conservancy’s FishFace project received a $750,000 prize from Google to develop a smartphone app that could be used on fishing boats worldwide. The technology could offer a low-cost way to manage fisheries, allowing more precise monitoring of stocks and better tracking of declining species.

Digital farming

Quick: Which country is the second-largest food exporter in the world behind the United States? Surprisingly, it’s the Netherlands.

The country has become a global produce rack even though it is 1/270th the size of the US and lies at the same latitude as Newfoundland. It has achieved this by being in the forefront of the “precision farming” revolution.

Around the world, farmers are increasingly tapping new technologies to increase yields. Drones and satellites provide infrared and thermal imagery that measure the photosynthesis rates of crops. Sensors embedded in fields relay moisture levels and allow farmers to remotely control their irrigation pumps from their smartphones. Even the farmer’s trusty water bucket has gone high-tech: The WatchDog wireless rainfall collector measures temperature and rainfall down to a hundredth of an inch – turning farmers into instant meteorologists.

All of this data can be aggregated to help growers divine when and where to plant seeds, spread fertilizer and lime, and spritz fields with pesticides. The monitoring reduces both labor costs and environmental waste.

The Dutch have pushed digital farming as far as anyone. Starting in the 1990s, scientists, businesses, and the government launched a concerted effort to produce twice the food with half the resources. Their efforts have paid off: By embracing efficient technologies and sustainable practices, the Netherlands now produces more tomatoes, potatoes, onions, carrots, pears, cucumbers, and peppers per square mile than any other nation.

To the airport, quickly

Imagine combining the velocity of a high-speed train with the personal comfort of your car. Put another way, how about zipping to the airport in your own private pod at 200 miles per hour?

That may soon happen on the wind-swept prairie outside Denver. The Los Angeles-based company Arrivo is planning to lay magnetized tracks alongside existing freeways to propel several different kinds of pods: some that carry people, some that haul cargo, and some that ferry cars on flatbed sleds. Proponents say the system will reduce traffic congestion by doing the work of five to 10 freeway lanes.

Arrivo has partnered with the Colorado Department of Transportation to build a half-mile test track near Denver International Airport. It’s part of a feasibility study to connect the airport to a business district in Aurora, a suburb of Denver about 10 miles away. Arrivo plans to begin construction in 2019, and says the transit system may be operational as early as 2021.

The project will use technology similar to the magnetic levitation trains that operate in Europe and Asia. Known as floating trains, they tap the power of supermagnets to lift rail cars and propel them down tracks. Maglev trains in China regularly travel at more than 260 m.p.h., while the Japanese have tested one that hit 375 m.p.h.

Even more advanced is the idea of hurtling passengers through vacuum tubes where there is no air resistance. Elon Musk envisions one day whisking passengers at 700 m.p.h. between San Francisco and Los Angeles with his Hyperloop, a segment of which is currently being built in the Nevada desert. Not to be outdone, China is researching a vacuum-tube train that it hopes will reach 2,500 m.p.h. But these transit systems are years, if not decades, away.

Moonshots 2.0

The moon is beckoning humans once again. Several lunar missions are planned for 2018 – and this time private industry will be in the mix. India and China both plan to send unmanned missions to the moon, while five privately funded teams are vying for $30 million offered by the Google Lunar XPRIZE competition.

The money will go to the first team to land a robot on the moon that travels 550 yards and transmits high-

definition video and images back to Earth. The teams are to complete their lunar missions by March 31, 2018.

Additionally, SpaceX, another of Elon Musk’s initiatives, aims to send two space tourists in orbit around the moon sometime in late 2018. They will fly aboard one of the firm’s Dragon 2 space capsules. The company is set to launch its first crewed mission in August, ferrying NASA astronauts to the International Space Station.

A soft pedal

Electric bicycles have been around since the 1890s, but they have long had a reputation of being ungainly, expensive, and heavy. Now advanced sensors and control systems are reviving the e-bike’s image – and its practicality as a form of urban transport in an era of irrepressible traffic congestion.

Superpedestrian, an e-bikemaker in Cambridge, Mass., has created the Copenhagen Wheel, which looks like a rear bicycle wheel with an oversized red disc as the hub. It uses data from sensors to estimate the torque, cadence, and position of the pedals to emulate the feel of riding a normal bike, only with far less effort, since the battery is doing most of the work.

“E-bikes will really get going when they start to feel like regular bikes, but the riders become superhuman,” says Assaf Biderman, Superpedestrian’s chief executive officer. “That’s when we know we’ve nailed it.”

The $1,500 wheel can be purchased as a replacement rear wheel for a standard bicycle. The company also sells bikes with the wheel built in.

Other e-vehicles are blurring the line between bike and car. The egg-shaped ELF, produced by the Durham, N.C., company Organic Transit, sports three wheels and an enclosed cab with solar panels on the roof. Retailing for about $9,000, it is powered by a combination of pedals and a solar-powered rechargeable battery. Two other bike/cars are plying roads in Germany – the Twike, a fully enclosed electric vehicle, and the four-wheeled Schaeffler Bio-Hybrid, which looks like a cross between a baby buggy and an all-terrain vehicle. It can be propelled by pedal power, batteries, or both at once.

Tailored TV

Ever want to be Steven Spielberg – create your own narrative? Now you can, in a way, with Mosaic, a murder-mystery app that allows you to choose which characters’ perspectives you want to follow.

Available on iTunes and Android platforms, Mosaic is a $20 million interactive online series directed by Steven Soderbergh. It stars Sharon Stone. The app also offers supplementary materials – police reports, voice mail, news clippings – for the viewer to explore, and you can always go back and rewatch the story from another character’s perspective. Mr. Soderbergh’s cut is set to air on HBO in January 2018.

Mosaic is part of a trend that is expected to grow in the future – interactive TV. Already, in 2017, two Netflix children’s shows – “Puss in Book: Trapped in an Epic Tale” and an episode of “Buddy Thunderstruck” – offer young viewers choices of different plots to follow as the series progresses.

Slicker cities

Cities of the future will be fitted with sensors that allow residents to instantly monitor everything from traffic to noise to air pollution. Roads will throb with autonomous vehicles – “taxibots” and “vanbots.” Garbage will be whisked away in underground vacuum tubes, and homes will be as wired as Los Alamos National Laboratory.

That, at least, is the vision of many urban planners, elements of which are emerging today.

In October, Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary of Alphabet, the company that owns Google, announced that it will commit $50 million to redesigning 12 acres of waterfront in Toronto as a “smart city.” Rechristened as Quayside, the neighborhood will be carpeted with sensors; road design will prioritize pedestrians, cyclists, and self-driving cars; and construction will emphasize prefabricated structures built with eco-friendly timber and plastic. If all goes well, the company will expand the project to 800 acres.

Billionaire Bill Gates is getting involved in the city-of-tomorrow movement, too. The former head of Microsoft plans to invest $80 million in a smart city on 25,000 acres on the western edge of Phoenix. Called Belmont, the community will include 80,000 homes.

“Belmont will create a forward-thinking

community with a communication and infrastructure spine that embraces cutting-edge technology, designed around high-speed digital networks, data centers, new manufacturing technologies and distribution models, autonomous vehicles and autonomous logistics hubs,” says Belmont Partners, a real estate investment group that is developing the land.

Another futuristic city that will soon be getting more visibility, when the Olympics open in Pyeongchang, South Korea, in February, is the Songdo International Business District. The 1,500-acre site, built on land reclaimed from the Yellow Sea 45 miles southwest of Seoul, features energy-efficient buildings, electric vehicle charging stations, and pneumatic waste-disposal systems.

Flying cabs

Uber may soon live up to its German name. The ride-hailing company says it will be testing flying taxi services in two cities – Los Angeles and Dallas/Fort Worth – beginning in 2020, with an eye toward offering its first commercial flights in 2023. The company expects to be operating thousands of flights each day by the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Uber envisions a fleet of electric flying vehicles equipped with multiple rotors that could take off and land vertically and reach speeds of as much as 200 miles per hour. It has partnered with a real estate investment company to develop 20 rooftop terminals in Los Angeles.

No stranger to regulatory battles, Uber recognizes that adding hundreds of on-

demand aircraft to already congested skies poses a huge challenge. Thus it has contracted with NASA to help develop an air traffic management system.

The firm sees the service as a way of making cities more livable. But skeptics point out that aircraft capable of vertical takeoff and landing have been historically unreliable and expensive. At best, they see them as an annoyance and at worst a danger to people on the ground. Besides, if an airborne taxi service were really such a great idea, critics note, wouldn’t Uber be trying it with existing aircraft?

Printing homes

3-D printing has been used to create everything from jet airliner components to custom-fit shoes. Many experts say the process of turning digital files into three-dimensional objects could ultimately usher in a new industrial revolution.

One of the latest manifestations of 3-D wizardry: building houses. It’s an application that could transform construction practices that have remained unchanged for centuries.

Using a swiveling robotic arm that extrudes concrete, a San Francisco company, Apis Cor, 3-D printed the concrete walls for a 400-square-foot house in Russia in less than 24 hours in early 2017. And researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge have built a robotic arm and a vehicle that dispenses concrete for a 50-foot-diameter, 12-foot-high dome in less than 14 hours.

The technology could greatly speed up the construction of homes and reduce the waste. Construction refuse accounts for half of all solid waste in the United States.

Robot-printed houses might also prove useful if humans ever try to colonize Mars or other areas of the cosmos. In November, NASA opened the third phase of its 3D-Printed Habitat Challenge, offering a $2 million prize for inventors who can print a foundation and a small home using indigenous materials.

Purer water

If you have a water filter in your refrigerator or on your kitchen faucet, you know it comes with one major drawback: The filter often has to be replaced.

Researchers at Princeton University in New Jersey have developed a way to clean water that may get around this problem: Infuse it with gas. It works by injecting carbon dioxide into a stream of water. When CO2 is dissolved in water, it creates ions that generate a small electric field. Because most contaminants have a surface charge, the electric field can split the stream into two channels, one carrying the contaminants and one containing clean water.

The researchers say that their method is 1,000 times as efficient as conventional filtration systems. They believe it could be useful in providing more sources of potable water in the developing world because of its low cost and low maintenance requirements. The technology could also find use in filtering water at desalination plants and water treatment facilities.

Wonder wafer

Graphene has been heralded as the next wonder material. A form of carbon that consists of a single layer of atoms, it is stronger than steel, harder than diamond, lighter than paper, and more conductive than copper.

It is currently being used in everything from electronics to high-tech tennis rackets. It may one day lead to smartphones as thin as paper that can be folded up and put in your pocket.

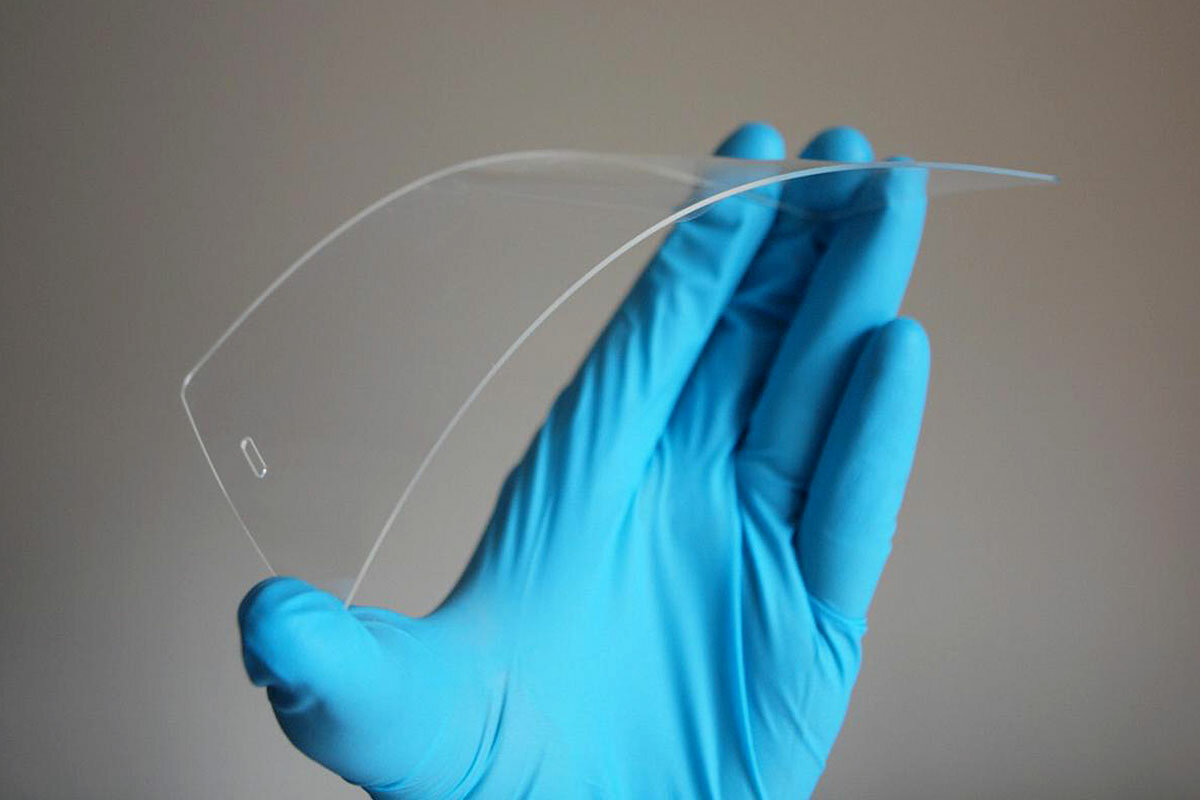

A team of physicists at the University of Sussex in England has for the first time combined silver nanowires with graphene to create a bendable, shatterproof touch screen. Because of graphene’s high conductivity, the screens could be more responsive and use far less power. They may be crucial to creating a new generation of credit-card-size phones.

New tools for firefighters

Firefighters are adopting technology that seems straight out of science fiction. For many departments in the United States, the toolkit includes the FIT-5, a grenade-like canister that douses flames with a potassium bicarbonate powder. It extinguishes flames better than water. Other departments are turning to PyroLance, a device that can shoot a high-pressure stream of water through concrete and steel to put out fires in inaccessible parts of buildings.

In the future, firefighters may bypass water altogether. Two engineering students at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., have developed a way to put out a fire using sound waves. The low-frequency waves from bass sounds push air away from the burning material to obliterate the flames. At Harvard University, a team has developed a wand that beams an electric current at fire to disrupt the combustion at the molecular level.

Other innovations are focused on firefighters’ mobility. This year, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, issued water-powered jetpacks to its fire crews to help them get around danger zones more easily. Ken Chen, a designer at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, has designed an exoskeleton – a wearable mobile machine – to help firefighters bound up the stairs of tall buildings and carry heavy loads.

A translator in your ear

Learning a foreign language has always been a culturally enriching experience as well as a benchmark of worldly sophistication: Wouldn’t we all like to casually drop into a conversation that we speak five languages? In the future, that may not matter.

Companies are coming closer to creating a universal translator – which, for better or worse, may obviate the need to Deutsch sprechen or parle français.

Google is among those leading the way. Its Google Translate service, launched in 2006, now offers real-time translation in more than 100 languages, from Afrikaans to Zulu. By combining the company’s new earpieces with the Pixel 2 phone, it puts a translator in a person’s ear.

Users press a button on the earbuds, speak in their native language, and the phone vocalizes the translation. Replies are then translated back. Sure, the conversations are somewhat halting – the devices are hardly as adept at translating languages as C-3PO from “Star Wars.” But they are quicker than fumbling through a translation dictionary.

‘AR’ you ready?

Augmented reality technology gained widespread attention in 2016 with the release of Pokémon Go, a location-based smartphone game that drew hordes of participants to public places. But gaming isn’t the only industry being transformed by AR, which superimposes a computer-generated image on a user’s view of the real world.

Home furnishing companies such as Cambria, IKEA, and Wayfair are using the technology to help consumers visualize what their couches and beds would look like in their homes. Mercedes-Benz offers an AR app for smartphones to replace traditional owners manuals. The cosmetics retailer MAC uses AR-enabled mirrors to paint their customers’ faces in virtual makeup.

The rise of AR could herald the return of smart glasses, which in the past were hampered by limited functionality and the awkwardness of wearing a bulky appendage. Google Glass Enterprise Edition, designed for the workplace, is currently being used in dozens of industrial settings. Companies such as General Electric, Boeing, and Volkswagen are reporting huge gains in productivity as workers wearing the glasses can, for instance, see step-by-step instructions of how to assemble a jet engine or install a trunk lid. A report by Forrester predicts that by 2025 nearly 14.4 million US workers will be wearing smart glasses.

Curbing global warming with fans

Climate change is caused mostly by human activity emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Part of the solution may lie in extracting the harmful pollutants from the air – and then recycling them in useful ways.

That, at least, is what the Swiss company Climeworks is banking on. On the roof of a recycling center outside Zurich, Switzerland, 18 fans suck in the surrounding air. Chemically coated filters absorb the carbon dioxide. When they are saturated, the filters are heated to produce pure CO2, which is pumped into a nearby greenhouse where it helps vegetables grow bigger. Climeworks estimates that its fans are about 1,000 times as efficient as photosynthesis, which draws carbon out of the atmosphere and turns it into plant material.

Climeworks was the first to commercially capture CO2 from ambient air, but it is just one of many companies around the world pursuing carbon capture as a way of mitigating climate change. Carbon Engineering, backed by Bill Gates, is testing air capture at a facility in British Columbia. New York-based Global Thermostat has two pilot plants drawing CO2 from the air and power-plant flues.

Why coal-rich Wyoming is turning to wind

When our reporter visited Wyoming to report this next piece, signs on the interstate warned of gusts topping 70 miles per hour. Politicians there are seeing practical signs, too – of an emerging power source that’s stronger than even staked-down ideology.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Wind power isn’t just for liberals and environmentalists anymore. As the economics of the wind industry have become more viable, many staunch conservatives have come to view wind power as a vital component of a diverse energy future. That shift is particularly apparent in coal-rich Wyoming, where a billionaire fossil fuel baron is bankrolling development of what is set to become the largest wind farm in the United States. Wyoming, like many fossil fuel-rich states, has been hit hard by the downturn in coal and declines in oil and natural gas prices. At the same time, ideologically driven investment in wind power from companies and states looking for cleaner energy and climate solutions has propelled the once fringe industry toward an economy of scale that appeals to fiscal conservatives. In Wyoming, wind development is increasingly hailed as an integral part of a diverse energy portfolio. "It takes decades to diversify a state’s economy," says the former head of the Wyoming Infrastructure Authority. “There will come a day when that last coal train leaves Wyoming.”

Why coal-rich Wyoming is turning to wind

It’s a sunny day in early November in southern Wyoming, but the wind is blowing so hard that opening a car door is a chore. Signs on the interstate warn of gusts topping 70 miles per hour, and semi trucks have pulled over all along I-80. It’s difficult to hear a word Bill Miller says as he steps out of his truck at the top of a rise on the Overland Trail Ranch to describe the development taking place on the expanse below him.

Of course, that fierce wind is exactly what makes this pocket of the West so desirable for that development. The Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project is slated to become the largest wind farm in the United States once it’s up and running. And it’s causing some in Wyoming – a state whose economy has been devastated by the decline of its bedrock fossil fuel industries – to rethink their attitude toward renewable energy.

The 3,000-megawatt project near Rawlins is emblematic of a growing industry that is hitting its stride, and is fueled less by ideology than by economics. Gone are the days when wind power advocacy fell exclusively to liberals and environmental advocates. As the economics of wind power have become more viable, many staunch conservatives have come to view the industry as a fiscally responsible component of a diverse energy future. The Chokecherry and Sierra Madre project is bankrolled by Philip Anschutz, a Denver billionaire who made much of his fortune in the fossil fuel industry, is a major Republican donor, and is hardly a poster child for renewable-energy idealism.

“We’re in the resource business,” says Mr. Miller, a native Wyomingite with a trim grey beard who grew up on a ranch and has worked for The Anschutz Corporation for 37 years, mostly on oil and gas projects. He now runs both the Power Company of Wyoming and the TransWest Express Transmission Project, the two Anschutz subsidiaries behind the wind farm and the transmission line that will carry its electricity from the expanses of Wyoming to urban California and the desert Southwest. “I try to ignore the political, ignore the policy, and think about it from an economic point of view.”

Anschutz already owned the 500-square-mile working cattle ranch where the new wind farm is being built, and as Miller drives its bumpy roads, up to a plateau overlooking the site, with Elk Mountain rising in the distance, he points to the primary reason this project made sense: “This is, without exception, the best wind resource anywhere in the US.”

For a state with such strong winds, Wyoming has actually been slow to enter the wind market. That honor goes to the Plains states like Texas, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Many of those states – which are generally conservative, and supported Donald Trump in 2016 – generate a significant portion of their power from wind.

When Kansas legislators voted two years ago to do away with its renewable portfolio standard mandating that 20 percent of the state’s electricity come from renewable sources by 2020, it was largely a symbolic action; more than 20 percent of Kansas’s power already came from wind energy by 2014. Today, about 30 percent of its electricity generation comes from wind.

“A combination of the [federal] tax credit and improving technology has made wind very cost effective,” says John Nielsen, clean energy program director at Western Resource Advocates in Boulder, Colo. One of the biggest barriers to development has been a lack of transmission and an antiquated grid system, but Mr. Nielsen and others say that once there’s more regional connectivity, wind can become an even larger player.

One key driver for the spike in wind has been the growing demand from companies and states looking for cleaner energy and climate solutions. That ideologically driven investment has propelled the industry toward an economy of scale that appeals to fiscal conservatives.

“In a lot of these more conservative states the driver is the economics,” says Nielsen. “Ten years ago, the barrier to renewables was that they were more costly. Now, the barrier to really large-scale penetration is the existing system, that it’s not as flexible as it could be to integrate these resources.”

Economic sense

Wyoming, despite its fierce winds, ranks 15th in wind capacity among US states. That’s a result of several factors: a lack of adequate transmission lines, particularly given that coal plants generally have the right of first transmission; ambivalence from residents who worry about the effect on treasured views or on the state’s iconic eagles; and marked antipathy from some Wyomingites who see wind as a threat to the coal, natural gas, and oil that have long been the bedrock of Wyoming’s economy. That antipathy is part of what drove the state to enact a $1-per-megawatt-hour tax on wind power – one of just two states to tax wind energy – and to repeal its sales-and-use tax exemption for utility-scale renewable-energy equipment. Between 2010 and 2016, when the US wind industry grew by more than 100 percent, wind in Wyoming grew by just 5 percent, with just one 80-megawatt project added.

But that’s changing. Along with the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre project, Rocky Mountain Power has announced plans to add at least 1,100 new megawatts of wind power by 2020, mostly in Wyoming. Viridis Eolia, a proposed wind farm near Medicine Bow, Wyo., just 50 miles east of Rawlins, would add nearly 2,000 megawatts of wind power if completed. The power company is also developing improvement projects to boost existing infrastructure and wind power capacity, including a new transmission line and a “repowering” of existing wind turbines with longer blades.

“It is a necessary part of Wyoming’s economic future,” says Jerimiah Rieman, director of Economic Diversification Strategy and Initiatives in the Wyoming governor’s office.

Wyoming, in many ways, is at an inflection point economically. Its economy has been hit hard by the downturn in coal, at the same time as prices for oil and natural gas have also dropped.

“It was kind of a perfect storm,” says Jonathan Naughton, director of the Wind Energy Research Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, speaking about the forces hitting Wyoming’s economy. “And the thing that’s starker in Wyoming is how much of our economy is extractive-mineral-based.”

Against that backdrop, wind is one of the few potential bright spots. The two fastest-growing jobs in America are solar panel installers and wind turbine technicians. Both are projected to more than double in the next decade, growing more than twice as fast as any other profession. The construction of big new projects promises both direct and indirect jobs for the duration of the construction. And while the actual number of permanent jobs at new wind farms is relatively small – certainly not equal to the coal and gas jobs being lost in the state – it’s one of the few industries in Wyoming that promises any growth, and those jobs can make a big difference locally.

If 6,000 new megawatts of wind is added to Wyoming, it could mean upwards of $2 billion in new tax revenue over 10 years for the state, more than $10 billion in new investment, and about 50,000 new job-years of employment, says Robert Godby, an economist at the University of Wyoming who helped author a study on the potential impact of wind energy in the state.

“It doesn’t fill the gap that has been left by coal, but it’s not zero, it’s a significant amount,” says Professor Godby. “In places like Medicine Bow or Rawlins, it could make all the difference in the world.”

Seeing hope in the wind

In Wyoming's Carbon County – home to both those towns, and named for its former coal mines – wind turbines are already a common sight, dotting the horizon all around Medicine Bow, and spinning rapidly amid the strong gusts.

“They grow on you for sure,” says Laine Anderson, director of wind operations for Rocky Mountain Power, as he drives among the turbines at the company’s Seven Mile Hill Wind Project. Like most Wyomingites, he used to curse the wind, Mr. Anderson notes. Now, he sees it differently. “It’s pretty amazing to see them spin, and know they’re not polluting, not costing any extra for fuel.”

And in Rawlins, a town of just under 10,000 in high desert sagebrush country, some residents are hopeful about the jobs the new wind farms may usher in.

“We don’t want all our eggs in one energy basket,” says Shawn Dahl, the fast-talking owner of Buck’s Sports Grill, which features photos of local sports and history on its walls and a “wind turbine” burger on its menu. “If you’re not three years ahead, you’re already 10 years behind.”

Still, plenty of obstacles in Wyoming remain. Some residents are fiercely opposed due to the viewshed, the extensive range from which the soaring turbines can be seen. (Not only do the turbines shoot up 200-300 feet into the sky, but aviation rules require lights at night, which might be seen 50 or 100 miles away in these open spaces.) Others are concerned about threats to wildlife. Wyoming has critical greater sage grouse habitat, and the state has excluded wind development in those corridors, since the turbines can have a negative effect on breeding. There are also the birds killed by blades. “We’re not killing sparrows in Wyoming. We’re killing eagles and hawks,” says Professor Naughton. “The public places a higher value on raptors than other birds.”

Proponents argue that most of these issues can be dealt with through conscientious siting and conservation efforts. Miller notes that he’s redesigned the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre farms five times as he’s worked to get the permitting done. The process has taken nearly 10 years and has been far more onerous and expensive than he anticipated. Along the way, he has focused on minimizing viewshed disturbance, and gathering and using the best possible research and studies about sage grouse, raptors, and other wildlife.

“I would not call us environmentalists, but we’re really good conservationists,” says Miller.

An even bigger obstacle to wind development has been uncertainty around taxes. The generation tax levied on wind power in 2010, combined with the 2009 elimination of the sales-and-use tax exemption, will cost the project an additional $440 million more in taxes over its economic life, says Miller – more than twice what was anticipated. Periodic attempts by some state legislators to raise that generation tax from $1 per megawatt-hour to $3 or even $5 per megawatt-hour likely would have killed it. Those efforts were defeated, and Miller and others say there seems to be much broader recognition on the part of both lawmakers and the governor of the self-inflicted harm Wyoming would do to itself economically if they were to price wind out, but the debate is not over.

“The attitude about the wind resource opportunity in Wyoming has done a significant shift in recent years,” says Miller, noting that he’s spent countless hours with county commissioners, state legislators, and other wind skeptics. “The state of Wyoming does have significant issues with their funding. But you can’t cure what’s happened to coal industry by taxing the wind industry out of the business.”

Beyond the coal v. wind mentality

Loyd Drain has been a tireless advocate for wind in Wyoming, especially during the five years he led the Wyoming Infrastructure Authority before stepping down to return to Texas as an energy consultant. It drives him crazy to hear detractors who see wind as the enemy of coal. Texas, he notes, is “a huge fossil fuel state,” but has had no problem also embracing wind – and has benefited from the boom as a result.

“It takes decades to diversify a state’s economy,” says Mr. Drain. “There will come a day when that last coal train leaves Wyoming.”

And when Drain (who also serves as a consultant to the proposed Viridis farm in Medicine Bow) looks at the steady drop in costs for wind, he thinks it’s only going to grow – especially if America’s antiquated grid system ever gets overhauled.

“I have no problem saying I’m a climate denier, because I am,” says Drain. “But if you give me the choice of buying coal, natural gas, solar, or wind, because of economics, because of my pocketbook, hands down I’m choosing wind.”

How Iceland is beating teen alcohol abuse

It took a societal shift in thought to veer from a hard-drinking youth culture to one in which widespread youth substance abuse is almost a nonissue.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Thorgeir Tryggvason promised his grandparents he would not drink until he was 20, the legal age. Now 21, he found it a promise easy to keep. “It is not ‘cool’ to drink in school like it was 20 years ago,” he says. That's a marked change. In the 1980s and ’90s, Icelandic youths were some of the hardest drinking kids in Europe. One 1998 survey found that 42 percent of 10th-graders said they had been drunk within the past 30 days. So parents, researchers, and local leaders got together and tried a new approach. The focus shifted from the responsibility of individual teenagers to group efforts like curfews for youths, the creation of after-school activities as alternatives to drinking, and the promotion of more parent-child quality time. It worked: A repeat of that 1998 survey in 2017 found only 5 percent of 10th-graders got drunk in the past 30 days. Now the model is being exported abroad – though whether it will achieve the same level of success remains to be seen.

How Iceland is beating teen alcohol abuse

In the late 1980s, when Björgvin Ívar Guðbrandsson was a teenager, alcohol and school dances went hand-in-hand. While he was later to drinking than his peers – more interested in playing soccer and guitar – when he did start around age 16, he would smuggle alcohol in his guitar case into school events.

“I think the adults just turned a blind eye,” says Mr. Guðbrandsson. “The culture was, I think, ‘they’re just kids. As long as they aren’t fighting, it’s okay.’”

Today, as a teacher at Langholt school in Reykjavik where he once studied, he says that if a student were to show up drunk to a dance, it would be such a scandal that the school principal would likely call child protective services.

In reality, that rarely happens because substance abuse on a wide scale has essentially become a “non-issue,” says Guðbrandsson. Alcohol and school dances, in other words, don’t go together in Iceland today.

This school is hardly alone. Teen drinking – as well as teen smoking, marijuana use, and abuse of other drugs – has plummeted across Iceland in the past two decades as academics, policy makers, and parents joined forces to clamp down. And now cities around the world are looking to this tiny island nation for clues on how to tackle underage drinking.

Yet beyond adolescent alcohol and drug use, Iceland has shifted thinking on youth culture itself, making it by many accounts more innocent and carefree. It has expanded parents’ notions of childhood and the importance of family time, while reinforcing the maxim that it “takes a village” to raise a child, says Hrefna Sigurjónsdóttir, director of the national umbrella for parental organizations in schools, Home and School, one of the key players in the federal-state government program now known as Youth in Iceland.

She calls it an “awakening” that has taken place at home, school, and beyond. “I think people are not confused anymore about, ‘is this kid an adult or not?’”

A different approach

Those lines were once blurrier. After Mr. Guðbrandsson graduated from school, teens were drinking even harder. In the 1990s, teen revellers packed downtown Reykjavik at 3 a.m. on weekends. Icelandic youths in fact were some of the hardest drinking kids in Europe at that time. In 1998, 42 percent of tenth graders surveyed in Iceland said they had been drunk within the last 30 days.

Prevention projects were established, similar to the American program Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.), built on the ethos of empowering teens to “just say no.”

Yet substance use kept going up, says Inga Dora Sigfúsdóttir, cofounder of the Icelandic Center for Social Research and Analysis (ICSRA), which is the data hub for Youth in Iceland. “A group of people came together, sat down and said, ‘we need to find a different approach. This is obviously not working.”

One of the problems was an ambiguous view of the line between child and adulthood, she says.

One of the most absolute rules to take effect was legal curfews: Kids ages 12 and younger must be home at 8 p.m. in the winter and 10 p.m. in the summer. Thirteen to 16-year-olds must be home at 10 p.m. in the winter and by midnight in the summer, even when the sun is still blazing. Icelandic parents in some communities carry out night patrols, with reflector vests and flashlights, to make sure kids are safely at home when they should be. Thousands of fridge magnets were sent to households, and still are, to remind children of the rules.

Parents began to sign agreements, through schools and parental organizations, with various pledges such as not allowing unsupervised parties in their homes or spending at least an hour a day with their children. “Twenty years back people were surprised,” Ms. Sigfúsdóttir says. “We had to change things here. We wanted to believe in this idea of ‘quality time,' and not having to spend too much time with them. We had to change a very liberal view towards adolescent drinking. People didn’t think it was important.”

'It’s the law. It’s on the refrigerator.'

Through the program, the municipalities funded and expanded after-school activities, from sports to gymnastics, to music, art, and ballet. The basic idea is to keep kids busy – and out of trouble – and help them find meaning in their lives that dissuades them from seeking alcohol or drugs in the first place.

The entire program is backed with data from yearly surveys that ask kids if they drink or how much time they spend with their parents, and requires constant dialogue between academics, policy makers, and people on the ground. For example, the data showed that getting a critical mass of parents to buy into the program was more important than getting every parent to do so.

At its heart, it takes the onus off the teens themselves – the opposite of the D.A.R.E. approach – and places it on the community.

“It does not concern teaching individual children about responsible choices, or even about making them responsible for their own behavior,” says Álfgeir Kristjánsson, a former data analyst at ICSRA who is now an assistant professor of public health at West Virginia University. “The Icelandic approach … is to strengthen the societal and protective factors and drive down risk factors.”

The program has transformed family life in Iceland. Ms. Sigurjónsdóttir, from Home and School, says that when she was 16 she moved from her rural community to Reykjavik. It is a common practice, since so many towns in Iceland don’t have upper secondary schools. She moved into an apartment with a friend her age. “We thought we were so adult but we weren’t really,” she says. “We had a lot of fun, but in hindsight it was hard as well. Sometimes you just need your mommy.”

Asked if she could imagine the same one day for her two young children, she responds immediately, “no way.”

Families report being a closer unit today. Seventy five percent of parents knew where their children were most of the time in 2014, compared to 52 percent in 2000, according to ICSRA data. Fifty percent of tenth graders said they were often or almost always with their parents on weeknights in 2014, more than twice the 23 percent in 2000.

Ultimately parents in Iceland say it’s made it easier to be a parent. They don’t have to battle with their kids over when and how often they are allowed out, says Baldvin Berndsen, a father of three. “I use it all the time. I say, ‘it’s not me. It’s the law. It’s on the refrigerator.”

Staying sober for sports

On a bone-chilling December afternoon, the sun has already set as girls and boys strap up after school for practice at the Throttur soccer club, which sits in the shadow of Iceland’s national stadium.

The municipality subsidizes children with a $500 coupon per year – about half the cost annually – to enroll in extracurriculars. Reykjavik’s Mayor Dagur Eggertsson says 80 percent of kids from age 6 to 18 take advantage of the program.

The number of registered players, from ages 5 to 18, has doubled in the past ten years to 1,000 at this club alone, says Gudberg Jonsson, another pioneer of Youth in Iceland and a research scientist at the Human Behavior Laboratory at the University of Iceland. That follows national trends.

Far from generating concerns that Icelandic youth are over-programmed, after-school leisure is considered among Youth in Iceland’s biggest successes. Their statistical analysis shows a clear correlation over time between engagement in activities and teenage sobriety.

In the suburb of Rima outside Reykjavik, Birta Zimsen, a 16-year-old in a maroon hoodie who won “Miss Tenth Grade” last year at the local school is taking a breather from basketball practice on a December evening. When asked if she drinks, she says no. “I play basketball," she says.

Sitting next to her is Thorgeir Tryggvason, who is 21 and at around 16 promised his grandparents he would not drink until he was 20, the legal age. He found it a promise easy to keep. “It is not ‘cool’ to drink in school like it was 20 years ago,” Mr. Tryggvason, an avid soccer player, says. “You were a ‘cool guy’ if you did sports.”

It doesn’t mean that teen drinking is completely eradicated. And Mr. Berndsen, who is president of the parents’ association at the school in Rima where his 14-year-old studies, says more could be done. He wants subsidies for sports for any student in the mandatory system to cover the cost entirely. He also wants parents in his community to resume night patrols that have ceased in recent years. He worries that the media is not accurately portraying the dangers of marijuana, and harder drug threats still exist. “The availability [of drugs] is out there, and I know kids here have said ‘I know someone that knows somebody who could get me whatever I need,’” he says.

Going global?

How replicable Iceland's model really is remains an unanswered question. Since 2006, Youth in Iceland has introduced their methods in 35 municipalities across Europe, an initiative called Youth in Europe.

And their phones keep ringing. A 2015 study, the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, measured the percentage of 15- and 16-year-old students who said they drank alcohol in the 30 days prior to the survey. It was 48 percent on average across Europe, compared to 9 percent in Iceland.

And Mr. Kristjánsson is currently introducing a version of Youth in Iceland in two counties in West Virginia. According to a Monitoring the Future study released in December, the rate of American 10th graders who said they’d been drunk in the last 30 days was 9 percent in 2017 – a decline over the long term, but still almost twice Iceland's rate today.

One of the biggest challenges Kristjánsson faces is cultural. “America is a country of individualism, we believe in individual choice and individual responsibility,” he says.

Sigfúsdóttir, who recently returned from Chile to introduce the program, says skeptics ask whether the model suits Iceland because it’s a small island nation. She counters with a slide she prepared showing Malta (also an island) and Lichtenstein (also tiny) where youth drinking rates far surpass those in her country – being small or surrounded by water doesn't make fighting alcohol abuse any easier.

She argues it is neither geography nor population that matters most when it comes to transferring Iceland's methods. It’s the fact that children and parents all over the world are essentially the same.

“That’s the beauty of it. It’s easy to get parents on board, because parents tend to love their kids," she says. “And if you give kids a choice of fun activities and substance use, they always take the fun activities. ... They want healthy lives.”

On Film

Our critic's 10 favorite movies of 2017

Peter Rainer watched about 275 movies on your behalf, roughly his annual average, before distilling this 10-best list. Many “best of” lists are framed as preludes to the Academy Awards, he notes, so he really tries to reach “beyond the borders of Oscarmania” for his picks. “If you haven't seen or even heard about some of my choices,” says Peter, “so much the better.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Peter Rainer Film critic

This year, movies felt overshadowed by Hollywood’s scandals. Still, on screen, women owned powerful, attention-getting roles – from Gal Gadot’s charging Wonder Woman to Sally Hawkins’s outsider artist in “Maudie.” Then there were those overlapping inspirational (if predictable) movies about British resilience in World War II. Next year may bring more pointed dramas. (Or not. Hollywood, aside from its headline-grabbing denizens, tends not to wade far into the weeds of controversy.) So which 2017 offerings delivered? One of many reasons to be grateful for Jordan Peele’s highly original “Get Out” is that it’s both terrifically funny-scary and also deftly expresses the paranoia underlying modern black-white tensions. “The Florida Project,” about wayfarers living week to week in run-down budget motels outside Disney World, was a remarkably lyrical evocation of childhood. The culture-clash comedy “The Big Sick” was scripted by a couple and felt true because it was rooted in their lives. And “The Phantom Thread” was a fascinating, inexorably creepy movie that, alas, Daniel Day-Lewis has said will be his last. (Click on the blue “read” button for the full set of 10 capsule reviews.)

Our critic's 10 favorite movies of 2017

This year, the movies of Hollywood were overshadowed by the scandals of Hollywood. The sexual depredations perpetrated by studio chiefs, directors, and actors took top billing in an ongoing cavalcade of accusations and apologias by no means exclusive to the movie business.

Under the circumstances, the movies themselves often seemed more like a sideshow than the main event. Some commentators attempted to bridge this gap by indulging in dubious psychobiography posing as criticism. Woody Allen’s admittedly not very good “Wonder Wheel” was a conspicuous recipient of this syndrome. His alleged crimes were cited as a way to indict his movie.

It is the height of naiveté to assume that only the pure of heart are capable of making good movies, or that “bad” people are incapable of creating great art. There are simply too many historical examples to the contrary. But I am also enough of a humanist to believe that, by definition, there is no such thing as inhumane art. D.W. Griffith was a great artist except when, as in “The Birth of a Nation,” he was a vile racist. Leni Riefenstahl was a great artist except when, as in “Triumph of the Will,” she was a vile Nazi propagandist. The list goes on.

Because I am a film critic and not a sociologist (though sometimes the disciplines overlap), I find it vacuous to discuss a movie’s “message” without first evaluating the movie’s worth. That is to say, I am beholden to point out that films with all the right socially conscious credentials – such as “Mudbound,” set in the virulent Jim Crow South, or “Detroit,” about the police brutality-inspired riots in the summer of 1967 – can nevertheless be subpar as movies. In the current highly charged political climate, it’s tempting to celebrate certain films as vehicles for social change while also dismissing, or ignoring, their deficiencies. To do this is to take the easy way out. One of the many reasons I was grateful for Jordan Peele’s highly original “Get Out” was because it’s a terrifically funny-scary jape that also expresses far more than any other current movie the paranoia underlying modern black-white tensions. You can champion it with a clear conscience, no special pleading required.

Movies, of course, often reflect the historical eras in which they are made, whether by design or circumstance. Given how long it takes to develop most films, it’s not surprising that we do not yet have Trump-era movies.

And yet I was nonetheless somewhat taken aback at how blithely apolitical most of 2017’s dramatic movies were (as opposed to such documentaries as the climate change treatises “Chasing Coral” and “An Inconvenient Sequel,” or John Ridley’s voluminous and evenhanded “Let it Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992,” which chronicled civil unrest in Los Angeles leading up to the Rodney King verdict).

The only movie that was reportedly rushed into production to connect with this year’s zeitgeist was Steven Spielberg’s “The Post,” a conventionally crafted freedom-of-the-press clarion call about The Washington Post and the Pentagon Papers that stars Tom Hanks as editor Ben Bradlee and Meryl Streep as Katharine Graham, the first female publisher of a major American newspaper. I suspect that the next year or two will bring far more pointed and contemporaneous dramas. Or not. Hollywood, aside from its headline-

grabbing denizens, has never waded very far into the weeds of controversy.

With all the international crises shaking up the world right now, Hollywood instead offered up surrogate crises from the past – inspirational stand-ins for the real deal. Perhaps this is why we had multiple, overlapping movies about British resilience during World War II: “Dunkirk,” “Darkest Hour,” and “Their Finest.” All feature comprehensible villains and predictable victories. You could argue that the onslaught of superhero sequels feeds the same need: Just substitute comic book baddies for terrorists.

2017 was also a movie year in which actresses, more so than actors, grabbed most of the attention-getting roles. Some of them, like Streep’s Katharine Graham, or Emma Stone’s Billie Jean King in “Battle of the Sexes,” were all about women triumphing over male privilege. I didn’t think Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman, with her spandex and lasso, was exactly a feminist breakthrough for the ages, but it was kicky watching her lead the charge. If we are talking female indomitability, I would rather cast my ballot for Sally Hawkins’s intensely watchful performances as the deaf-mute cleaning woman in “The Shape of Water” and the hobbled outsider artist in “Maudie.”

The most resonant roles for women centered on the sometimes loving, frequently fraught relationships between mother and daughter as displayed in such films as “The Florida Project” (where the roles were played by Bria Vinaite and Brooklynn Kimberly Prince); “Marjorie Prime” (Lois Smith and Geena Davis); “The Big Sick” (Holly Hunter and Zoe Kazan); and “Lady Bird” (Laurie Metcalf and Saoirse Ronan). I suppose I should also include here Allison Janney and Margot Robbie in “I, Tonya,” except resonant is not exactly how I would describe their one-note face-offs.

But enough of my carping and cavils. Onward and upward to my top 10 list, in roughly descending order:

The Florida Project: Sean Baker’s movie about wayfarers living week to week in run-down budget motels outside Disney World is one of the most lyrical evocations of childhood I’ve ever seen. As a harried motel manager, Willem Dafoe gives his finest performance to date, and the mother-daughter teaming of Vinaite and Prince is peerless.

Get Out: The most astonishing writing-directing debut in years, Peele’s mash-up of horror and comedy and social satire is, also, flabbergastingly, the most trenchant new movie about American race relations.

Afterimage: The great Polish director Andrzej Wajda’s final film, and one of his best, features a towering performance by Boguslaw Linda as a real-life Polish avant-garde artist suffering for his intransigence under Communism.

Ex Libris: The New York Public Library: Fred Wiseman’s novelistically rich documentary is a celebration not only of a great New York institution but also the people who serve and inhabit its many branches. It’s ultimately about the sense of freedom that a great library can engender.

Faces Places: The great 89-year-old French New Wave director Agnès Varda, and the photographer and muralist known as JR, who is 34, travel the French countryside creating large-scale photo portraits of villagers that they then plaster onto the sides of buildings. From this unlikely pairing arises a near-masterpiece of a documentary that, in its evocation of friendship and mortality, is both gently, piercingly humane and wonderfully funny.

The Breadwinner: Animator Nora Twomey’s small gem, wistful and harrowing, is about a girl in Kabul, Afghanistan, who fights to rescue her family from the Taliban.

The Big Sick: A culture-clash comedy about a Pakistani-born Muslim stand-up comic and an American grad student, and the mayhem that ensues when she becomes seriously ill and both sets of parents frantically intervene. The script by married couple Emily V. Gordon and Kumail Nanjiani, who also co-stars with Zoe Kazan, is based on their lives, and perhaps that’s why it feels so true.

Kedi: A documentary about Istanbul’s teeming population of stray cats may not sound very promising, but director Ceyda Torun brings us right inside the felines’ world and, in the process, offers up a rhapsodic portrait of the people who care for them and the thronged Turkish city they share.

The Phantom Thread: Daniel Day-Lewis plays a famed dressmaker in 1950s London in Paul Thomas Anderson’s fascinating, inexorably creepy movie that Day-Lewis has stated will be his last. Say it ain’t so.

Mother!: I realize I’m going to take some heat for putting this widely loathed film on my best list, especially since I was less than enthused by the overrated critic faves “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” and “Call Me by Your Name,” but Darren Aronofsky’s fantasia about a self-infatuated poet (Javier Bardem) and his suffering muse of a wife (Jennifer Lawrence) is, like “Get Out,” both horrific and satiric in ways that move beyond the easy confines of genre.

In addition to the films favorably cited above, I would also single out “1945,” “The Wedding Plan,” “Novitiate,” “First They Killed My Father,” “Dawson City: Frozen Time,” and “Baby Driver.”

A message of love

Year-end revelry

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

States make headway on opioid abuse

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

There are hopeful signs that suggest a corner is slowly being turned on opioids as 2018 rings in. In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, for example, partial-year estimates for 2017 show drops of 10 percent and 9 percent, respectively, in overdose deaths. Massachusetts was the first of what are now many states that limit the number of opioid pills doctors can prescribe per prescription. And more people who overdose in the state are surviving as first responders use an overdose-reversing drug. Americans take opioids at four times the rate that Britons do and six times more often than people in France or Portugal. One reason: Writing a prescription provides a quicker and simpler form of treatment than non-drug therapies. As one medical-school professor notes: “Most insurance, especially for poor people, won’t pay for anything but a pill.” In 2018 the federal government may yet decide to play a more robust role. In the meantime, states and communities are beginning to find and implement programs that show promise of helping.

States make headway on opioid abuse

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculates that 91 Americans die each day from opioid drug overdoses. As 2017 draws to a close it now seems likely that average life expectancy in the United States will drop for the second year in a row – with opioid overdoses a big factor.

Drug overdoses accounted for more than 63,000 deaths in 2016, with more than 42,000 of them opioids, such as fentanyl, often prescribed by physicians to relieve pain. Opioid deaths have doubled since 2010.

But in some New England states there are hopeful signs that suggest a corner may be turning as 2018 rings in. Little by little, states and communities across the country are finding out what can help and taking action.

In Massachusetts and Rhode Island partial year estimates for 2017 show drops of 10 percent and 9 percent respectively in overdose deaths. Vermont and New Hampshire may see slight decreases as well.

Massachusetts was the first of what are now many states that limit the number of opioid pills doctors can prescribe per prescription. And more people who overdose in the state are surviving as first responders widely use naloxone, an overdose-reversing drug.

Michigan has seen heroin and prescription opioid overdose deaths double over the past five years. In response a package of new laws now includes a seven-day limit on opioid prescriptions and establishes an online database to ensure those addicted don’t jump from doctor to doctor to get quick refills.

In Colorado, Kaiser Permanente offers a $100 eight-week course to help patients recognize the dangers of opioid use. Participants learn that higher doses and longer periods of use increase the possibility of addiction. The program also offers alternatives to drugs, such as physical therapy, exercise, and meditation. The program has seen opioid use by patients drop significantly.

Americans take opioids at four times the rate that Britons do and six times more often than people in France or Portugal. One reason: Writing a prescription provides a quicker and simpler form of treatment than non-drug therapies.

“Most insurance, especially for poor people, won’t pay for anything but a pill,” says Judith Feinberg, professor in the Department of Behavioral Medicine & Psychiatry at the West Virginia University School of Medicine.

“Say you have a patient that [has] lower back pain,” she said in a BBC interview. “Really the best thing is physical therapy, but no one will pay for that. So doctors get very ready to pull out the prescription pad....”

“Other countries deal with pain in much healthier ways,” Dr. Feinberg adds.

In October, President Trump declared opioids a public health emergency, but he failed to ask for any substantial new funding to deal with the crisis. More recently he made a personal gesture of support by offering $100,000 from his presidential salary to address the problem.

In 2018 the federal government may yet decide to play a more robust role. In the meantime states and communities are beginning to find and implement programs that show promise of helping.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘First on any list’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Heidi K. Van Patten

The beginning of a new year can inspire a feeling of renewal and a readiness to get things done. But despite our best efforts, sometimes time constraints or limited resources can leave us feeling overwhelmed and helpless. When today’s contributor found herself in that situation, she paused to consider Christ Jesus’ point that loving God and loving others are the two most important things to do. Everyone is capable of doing this because we are the creation of divine Love itself. Striving to let that love motivate all we do awakens more love in the world and enlightens our daily activities in ways that meet our needs and others’.

‘First on any list’

The beginning of a new year can inspire a feeling of renewal and a readiness to get things done. We might vow to tackle household projects we’ve put off, to work harder at our jobs or at school, or to get in better shape physically.

I like to make lists of the things I plan to do, and I always feel accomplished as I cross off each task and move on to the next. Not long ago, however, I was adding jobs to my list faster than I could cross them off. Time constraints and limited resources left me feeling overwhelmed and helpless.

As the pressure and stress mounted, I decided I needed to forget my list for a moment – I wasn’t getting anything accomplished anyway! – and pray. For me, praying often begins with putting aside my worries and plans and letting my thought be quiet. Then I can listen for direction from God, who I understand as the universal Mind that expresses intelligence, order, and clarity in its spiritual creation, which includes each one of us.

Very soon a question came to my thought: What if all I had to do today was to love? This wasn’t what I’d expected. Actually, I had kind of hoped my prayer would lead me to some practical ideas about how to get everything done. Still, I did find this to be a very freeing thought, so I began to really consider it.

I remembered that once when Christ Jesus was asked what the most important law was, he answered by citing two commandments from the Hebrew Scriptures: “ ‘Love the Lord your God with all your passion and prayer and intelligence.’ This is the most important, the first on any list. But there is a second to set alongside it: ‘Love others as well as you love yourself’ ” (Matthew 22:37-39, Eugene Peterson, “The Message”).

I thought, How do I make this kind of love my first priority? I can start by gratefully and humbly acknowledging God as infinite Love and the source of all the love we express, then check my thoughts and actions throughout the day to be sure they are guided by Love.