- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Iran protests: Is an outward-focused regime out of step at home?

- In St. Louis, a new activism emerges as a legacy of Ferguson

- Morocco press freedom slips, and social media fills the gap

- As San Antonio’s 300th nears, some Texas history gets a rethink

- To boost young readers, digital books in their native tongues

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for January 2, 2018

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

The report is depressing and makes no attempt to hide it. “Let’s be honest: 2018 doesn’t feel good,” the Eurasia Group analysis begins. From there, it gets worse. “Citizens are divided. Governments aren't doing much governing. And the global order is unraveling.”

The report predicts a “geopolitical depression” – a decline of global stability – on the scale of the 2008 economic crash.

The prediction encapsulates a malaise that we so often see in the news today. The problem, the report suggests, is not necessarily that the world is becoming more dangerous. It is that the democracies that have upheld values such as freedom, individual rights, and openness since World War II are having a collective identity crisis.

This is the challenge of democracy and of freedom and peace. The more successful they are, the easier it is for vigilance to wane. “We took our liberal democratic values for granted for so long, we’ve forgotten how to defend them,” New York Times columnist David Brooks writes.

But this is also the virtue of democracy and of freedom and peace. The solution is in our hands. For his part, Mr. Brooks has written a series of extraordinary columns on how effective democracy demands its citizens to aspire to and strive for the best in themselves – the best motives, the highest ideals, the broadest compassion. That is a prescription for a very different 2018.

In our five stories today, we look at a unique effort to break down racial barriers in St. Louis, Morocco’s struggles to embrace a truly open democracy, and a new trend that could change literacy efforts worldwide.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Iran protests: Is an outward-focused regime out of step at home?

In Iran, frustrations with an underperforming economy are exacerbating other fault lines in society, from misgivings about an adventurist foreign policy to anger at ruling elites. The result has been violent protests. Sound familiar?

When hard-line factions sent protesters into the streets Dec. 28 in the Iranian shrine city of Mashhad, their target was the economic policy of their political rival, moderate President Hassan Rouhani. In part, the hard-liners miscalculated. In the ensuing six days of burgeoning protests across the country, in which 22 people have been killed, Iranians have expressed anger at the top clerical leadership. Protesters from even remote corners of the nation often considered to be bastions of regime support have even torn down posters of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. But one thing the hard-liners got right is the discontent over high levels of poverty and unemployment, the lack of a peace dividend from the nuclear deal, and persistent corruption. Mr. Khamenei tried Tuesday to blame foreign “enemies” for the protests. But analysts were dismissive. “To now suddenly come and deny the existence of all of these grievances, and say this is all agitation … is a very difficult sell,” Abbas Milani, director of Iranian studies at Stanford University, told the BBC. “People are rising up and saying, ‘Enough is enough. Enough corruption, enough incompetence.’ ”

Iran protests: Is an outward-focused regime out of step at home?

The violent protests in Iran that entered their sixth day Tuesday have brought to the surface several underlying and destabilizing forces in Iranian society, among them anger at the top clerical leadership and a degree of resentment at some of the government’s cherished foreign policy commitments.

The protests, which have delivered the worst scenes of unrest witnessed in the Islamic Republic since millions took to the streets over a disputed presidential vote in 2009, have so far left 22 people dead. They have also exposed a political miscalculation by hard-line foes of President Hassan Rouhani, by launching the protests in an effort to discredit his economic policies, then seeing them spin violently out of control.

Still, the protests are fundamentally about the economy more than anything else, say analysts in Iran: stubbornly high poverty and unemployment, the failure to extract a peace dividend from the much-heralded 2015 nuclear deal, and the continuing problem of entrenched corruption that was one of Mr. Rouhani’s own rallying cries in the last election.

The protests began in the shrine city of Mashhad as an attempt by hard-line factions to undermine Rouhani. But as they have morphed into a broader, nationwide public challenge against Iran’s top leadership, protesters from even remote corners of the nation often considered to be bastions of regime support have torn down posters of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and chanted “Death to the Dictator!”

The numbers of people on the streets are far smaller than in 2009 – several tens of thousands in total, it appears this time – but the protests have been fueled by a constellation of reasons for discontent, including Rouhani’s latest austerity budget.

Still, in his first public comments since the violence began, Ayatollah Khamenei accused “the enemies of Iran, using various tools at their disposal, including money, weapons, political means and their security apparatuses,” to harm the Islamic Republic.

“The enemy is waiting for an opportunity, for a crack to enter and interfere,” said Khamenei.

He made no reference to economic misery, though such concerns – and Rouhani’s checkered economic scorecard – dominated the presidential election last May. As protests mounted, Rouhani said the economy needed “major surgery” and that “people are angry about corruption and demand transparency.”

'No to Gaza, no to Lebanon.'

One target for protesters’ chants has been Iran’s years-long and expensive projection of power abroad, especially in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, where Iran has spent billions of dollars propping up Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, creating Shiite militias in Iraq to fight Islamic State (ISIS), and ensuring the military prowess of its vital ally, the Lebanese Shiite movement Hezbollah.

While that effort has given Iran more influence and leverage across the Middle East than at any other time since the 1979 Islamic revolution – and turned the commander of the Revolutionary Guard’s Qods Force, Maj. Gen. Qasim Soleimani, into a national hero in Iran – the cost has raised some eyebrows.

“Leave Syria, find a solution for us!” is one chant heard on the streets, where social media and even state television have shown buildings and cars on fire and military bases under attack. Another chant has been: “No to Gaza, no to Lebanon, we sacrifice our lives for Iran!”

From the outside, it may appear easy to connect the dots between the costs of Iran’s intervention abroad and the scale of domestic economic woe. But analysts inside the country say Iran’s current unprecedented status in the Middle East is not likely to have been made at the expense of economic prosperity at home, where mismanagement and corruption are more critical factors.

“Frankly speaking, these are arguments which protesters try to hide behind; I don’t believe that even half of one percent of the GDP of Iran is allocated for Syria or Yemen,” says Saeed Laylaz, a reformist economist and former presidential adviser in Tehran who spent time in prison for his reformist affiliations.

“These are arguments, but people are poor,” says Mr. Laylaz. ‘This is the fact that around 30 million Iranians are under the relative poverty line.”

Millions are hungry

Iran’s gross domestic product has grown roughly 20 percent in the past five years, and inflation during Rouhani’s 4-1/2 years in office has dropped from 40 percent to 10 percent. But food prices remain high, and few Iranians feel the benefit of the landmark nuclear deal, which Rouhani promised would bring prosperity as US and other sanctions were lifted.

Officials have stated that 12 million Iranians out of a population of some 81 million are living under the “absolute” poverty line. Laylaz suggests that some 3 million Iranians go to bed hungry every night.

For a country that received hundreds of billions of dollars in oil revenue over the past decade, “it shows that the government of Iran has an absolutely bad performance,” Laylaz says.

Still, he estimates that only 20,000 or 30,000 people nationwide are taking part in the current protests, many of them lower and working class – not Iran’s large middle class that formed the backbone of the far larger 2009 Green Movement protests. Iran’s substantial reformist faction and leaders have so far steered clear of the current unrest.

Iran’s interventions abroad – ostensibly to fight ISIS and “terrorists” beyond Iran’s borders, commanders say, and in their view as a means of exporting Iran’s revolution through proxy Shiite forces – have long been a subject of complaint when times get tough.

“It’s only logical for many people to come to that conclusion when there is so much unemployment, factories are laying off people, and many of the people out of universities also have no job,” says a veteran political analyst in Tehran who asked not to be named. “People think: ‘Why is our government spending so much money out there, instead of creating jobs for us?’ It’s a relatively widespread assumption.”

Similar slogans appeared in 2009 also, about Iran’s support for Gaza and Hezbollah’s war with Israel in 2006, and Iran’s large payments in the aftermath to help rebuild Hezbollah’s strongholds in Beirut and southern Lebanon.

Cash for religious institutions

But more recently, other economic issues have made headlines in Iran. Rouhani last month, for example, criticized and detailed for the first time how large volumes of cash are given to religious and cultural institutions, and the out-sized role they play in Iran’s economy. His budget proposed welfare cuts and a rise in fuel prices.

On top of that, millions of investors have also been stung by the collapse of unauthorized lending companies that grew during the free-wheeling era of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

“Mr. Rouhani did a good job to shed light on where the money goes in the nation,” says the Tehran analyst.

“There are many, many little things, but when you put them together, it created a very interesting background for this riot to happen,” he says. “It’s not happening in a vacuum.”

Nor is there a single overriding grievance, with a host of economic concerns – including the cost of foreign intervention – all bundled together.

“Always there is a portion of extremists who are against Iran’s role in the Islamic world,” says Mojtaba Mousavi, a conservative analyst and founder of the IransView.com website, noting the similar chants against Iranian support for Palestinian militants and Hezbollah in 2009.

“They began to talk about money spent in foreign countries in [Western] media … but it is important to note that despite their powerful propaganda, this time many reformists are supporting Iran’s role in Syria, Iraq, etc.,” says Mr. Mousavi.

“Chants against Iran’s role in Syria are not even that popular in the protests,” he says. “Poor people may be frustrated by corruption, but they know Qods Force is essential for their security.”

Change of tune in hard-line media

As the protests have evolved, so has the careful balance struck by hard-line media in Iran, which – like a number of hard-line officials – first supported the protests as a legitimate complaint against Rouhani, but have now seen that effort backfire.

At the start of protests on Dec. 28, for example, Kayhan newspaper described them as a popular uprising. And yet by Jan. 2, reflecting the surprise within Iran’s leadership at how quickly the protests spun out of control and turned destructive, Kayhan said the rioters were “pettier than worthless ISIS remnants.”

Such change won’t go unnoticed, as Iranian judicial officials declare that a crackdown is imminent, and that culprits could face charges of “warring against God” – a crime in Iran that can carry the death penalty.

In the weeks prior to the protests, Iranian leaders “acknowledged that there were serious economic hardships, that the poor people of Iran were under pressure,” Abbas Milani, director of the Iranian studies program at Stanford University, told the BBC.

“To now suddenly come and deny the existence of all of these grievances, and say this is all agitation, this is all foreign inspired, is a very difficult sell,” said Professor Milani. He noted that Iran’s most conservative centers have seen some of the most damaging protests.

“These are the places where people are rising up and saying, ‘Enough is enough. Enough corruption, enough incompetence, enough allotment of incredible sums of money to religious institutions that basically do nothing,’” said Milani. “It’s been an accumulation … that has now boiled into discontent in the ranks of the people who were supposedly the most solid base for the regime.”

Share this article

Link copied.

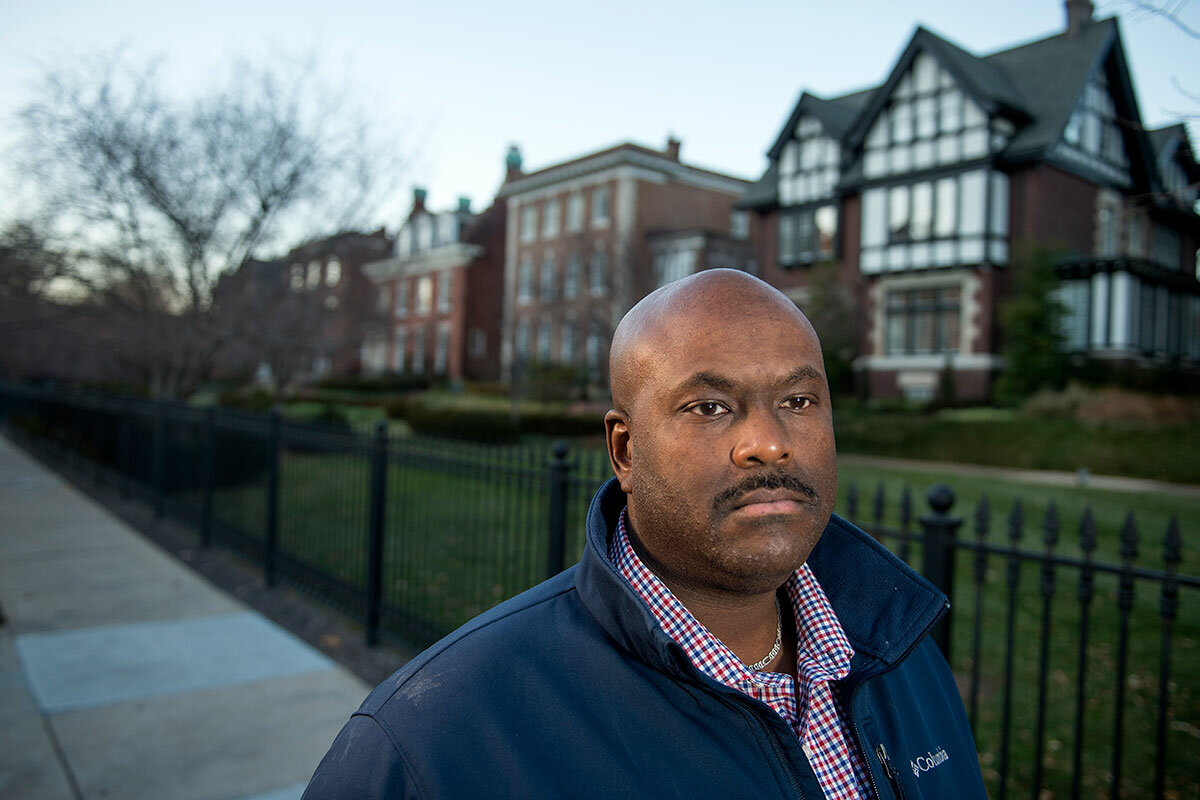

In St. Louis, a new activism emerges as a legacy of Ferguson

Time and again, our reporters have found that the steps to better racial harmony begin with open hearts and minds. The tough work is in overcoming the resistance to reaching out and really listening. So that's where St. Louis has started.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

St. Louis still lags behind many other US cities in instituting police and criminal justice reforms. But three years after violence flared in nearby Ferguson, Mo., after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old, by a white police officer, the city is pressing for change. A range of grass-roots initiatives has sprung up in which white people are increasingly joining a spirited crusade by black people to foster racial equity across the greater St. Louis area. They see their Midwestern city as a modern Selma, Ala., fueling a new civil rights movement. In schools, courts, and churches, they are combating the city’s long history of segregation and racism – and building on the often-forgotten pioneers of civil rights in Missouri. And while not everyone is happy with the new activism, work done here stands to provide a path forward for a country cleaved by racial division. That’s the view of the Rev. Darryl Gray, who participated in the original civil rights movement and has been a major force behind the drive here. “If we can be as successful in St. Louis as Dr. King and the civil rights leaders were in Selma,” he says, “it could change this country as Selma did.”

In St. Louis, a new activism emerges as a legacy of Ferguson

Elyssa Sullivan never expected to get thrown in jail. The white suburban mother lives in a tony enclave on the outskirts of St. Louis with street names like Joy and Glen, a world apart from the turmoil that erupted 16 miles away in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014.

She had no inclination to join the protests sparked by a white policeman’s fatal shooting of Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old, that overnight triggered a fraught – and painfully familiar – national debate on race relations in the United States.

“I was really scared,” says Ms. Sullivan. “I kind of bought that narrative, ‘Oh, that city is on fire; look at those protesters. I care about what they’re saying, but that’s not my place.’ ”

She never thought that three years later she would count a former battle rapper among her personal role models, or that she would scrawl “White Moms for Black Lives” on poster board and march down a highway. She couldn’t imagine that a police officer would yell obscenities at her – and another would zip-tie her wrists together.

But there came a point when Sullivan concluded that it was more dangerous for her to sit at home, ignoring what she now sees as an unequal justice system for black and white people, than to drive her minivan downtown and stand face to face with police in riot gear. Even if it meant spending a night in jail, as she ended up doing, unable to get an answer about the charge against her and denied a phone call to her husband and two kids.

“It just made me hyperaware of how no one is listening when people of color in our community have shared their stories of how they’ve been brutalized by police and damaged by police,” she says.

Sullivan is part of a broad movement that has sprung out of Ferguson, in which white people are increasingly joining a spirited crusade by black people to foster racial equity in St. Louis. They see the Midwestern city as a modern Selma, Ala., fueling a new civil rights movement. From schools to homes, from courts to churches, they are combating the city’s long history of segregation and racism – and building on the often-forgotten pioneers of civil rights in Missouri.

While St. Louis still lags behind many other cities in instituting police and criminal justice reforms, Ferguson has acted as a catalyst for change, from more grass-roots political engagement to the departure of a much-criticized police chief. Perhaps more important, it has led to a more frank dialogue between black and white people that could provide a path forward for a country cleaved by racial division.

“If we can be as successful in St. Louis as Dr. King and the civil rights leaders were in Selma, it could change this country as Selma did,” says the Rev. Darryl Gray, who participated in the original civil rights movement and has been a major force behind the drive here.

In the immediate aftermath of the Ferguson shooting, activists sensed the mood was right here and across the country for a major new push forward on social reforms.

But the election of Donald Trump and the emboldening of the white supremacist movement, combined with few convictions in police shooting cases around the country, dashed many of their hopes. Then, a few months ago, a St. Louis judge acquitted Jason Stockley, a white ex-police officer, in the shooting death of African-American Anthony Lamar Smith in 2011.

Mr. Stockley had pursued Mr. Smith, who was on parole for possession of marijuana and an illegal firearm, after witnessing a suspected drug deal. When the car chase ended in a crash, Stockley approached Smith’s vehicle and shot him, later testifying that he saw a gun in the suspect’s hands.

Heroin and a gun were found in the car, and an FBI investigation ended without prosecution of Stockley, a West Point graduate and Iraq War veteran. But after the officer had left the force in 2013, and the department had paid a $900,000 settlement to the Smith family, fresh evidence surfaced showing that the gun in Smith’s car bore only Stockley’s DNA. The prosecution argued it had been planted by the officer.

Stockley’s acquittal in the face of the new information stunned many who had worked for systemic change post-Ferguson, and it ignited a fresh round of protests.

Yet this time something was different. More than half the faces were white. That was intentional, taking a page out of the Selma playbook, says Mr. Gray.

In 1965, after state troopers brutally thwarted a march from Selma to Montgomery, Martin Luther King Jr. put out a call for whites to join them. Marching as a united front against voter discrimination, they reached Montgomery and helped persuade President Lyndon Johnson to enact the Voting Rights Act.

Adopting that strategy in St. Louis, black and white people have been protesting together amid trendy cafes and fancy suburban malls, challenging the idea that racial inequity is only a worry in neighborhoods with broken windows and empty streets.

Not everyone is happy with the new activism.

Some conservative whites believe it is misguided. They see rallying around black victims with suspected or demonstrated criminal backgrounds, questioning court verdicts, paying large settlements to families of police-shooting victims despite investigations clearing the officers, and forcing police officers to move away from the city as undermining law and order.

Yet the new social movement extends far beyond street protests. It involves a broad range of initiatives – many of them involving people of all colors working together – springing up everywhere from preschools to Pottery Barn-furnished living rooms.

Tiffany Robertson watched her neighborhood turn toxic after a police shooting, this one of VonDerrit Meyers Jr., a young black man, in 2014.

“There was so much polarization in the community ... I didn’t want to choose a side,” says Ms. Robertson, who is African-American. “I didn’t want my children to choose a side.”

So she started Touchy Topics Tuesday and invited white people to ask tough questions. She posed one of her own: “What about my skin offends you?”

The group has evolved to include a diverse mix of people, from airline pilots to police officers. Participant Sarah Riss has started another branch, in Webster Groves, where Sullivan lives, and she also runs the Alliance for Interracial Dignity, a group that promotes racial equity.

Other bridge-building efforts have focused on children. Laura Horwitz and Adelaide Lancaster, two white mothers, have started We Stories, which helps parents spark conversations about race and racism through children’s books. In two years, more than 550 families in 67 different ZIP Codes have been through their program. Several hundred more are on a waiting list.

City Garden Montessori was spearheaded by two mothers – one white, one black – who wanted a school with kids from a rich mix of racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. The school, which gets two applicants for every available slot, has become a model of integrated education and an avenue for improving cross-racial understanding and cooperation.

“It was a bit of an experiment to see if we are all coming together around our children and engaging in each other’s lives in ways that we would not be otherwise,” says executive director Christie Huck. “Can we begin to break down barriers and build meaningful relationships across race and class and strive to interrupt racism and these patterns that keep our region stuck?”

Witnessing Whiteness, a group inspired by a book of the same name, holds workshops to help people “notice and respond to interpersonal, institutional and cultural racism.” Sisters CARE – Christians Advocating Racial Equality – brings together a diverse range of Christian women to foster understanding. Other parent groups are pushing for more equity in schools.

“The old PTO guard is scratching their heads, like, ‘Why is there so much juice around this racial equity conversation?’ And they are figuring out how to support it,” says Farrell Carfield of Webster Groves, noting that her Parent Teacher Organization enthusiastically contributed funding.

“St. Louis certainly has the potential for being a model for creating ... important systemic change,” says Adia Harvey Wingfield, a sociology professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “But only if the conversations that are happening now are coupled with actual attempts to address the institutional processes that maintain racial and gender inequality.”

The solution to St. Louis’s problems may lie as much in how those of the same race deal with each other as in cross-racial work. Consider the experience of police Sgt. Charles Lowe. On a sultry night in July 2015, he was moonlighting as a private security guard when an intuition told him to put his bulletproof vest back on.

The African-American officer was still wearing his police uniform after getting off his shift at 2 a.m. He had done a walk around the property, then gotten back into his car, taken off his vest, and turned up the air conditioning. The impulse was insistent: “Put the vest on.”

Lowe, who says he felt a divine presence, heeded the directive. He also became aware of two young black men nearby. Soon a third arrived. They must be waiting for an early morning bus, he told himself. Then they disappeared.

Suddenly, a Ford pulled up. A guy got out, gun in hand. Lowe caught a glimpse of those inside. He was sure it was the men he’d seen moments ago.

The gunman fired at him through the front windshield. Lowe shot back, feeling midway through emptying his weapon that he’d been hit on his side. But, in fact, the bullet had lodged in his vest. While immensely grateful to be alive, Lowe has a question for his fellow African-Americans.

“I’m black, I got shot, and I’m a policeman fighting every day to make this community safe. Doesn’t my life matter?” asks the 15-year police veteran. “Or was it because I was wearing a blue uniform that it doesn’t matter?”

The Brown shooting unleashed a wave of African-American fury toward white police officers, who continue to be heavily criticized. But African-American officers such as Lowe are not exempt from such scrutiny. Within their own communities, they face distrust and even outright hostility.

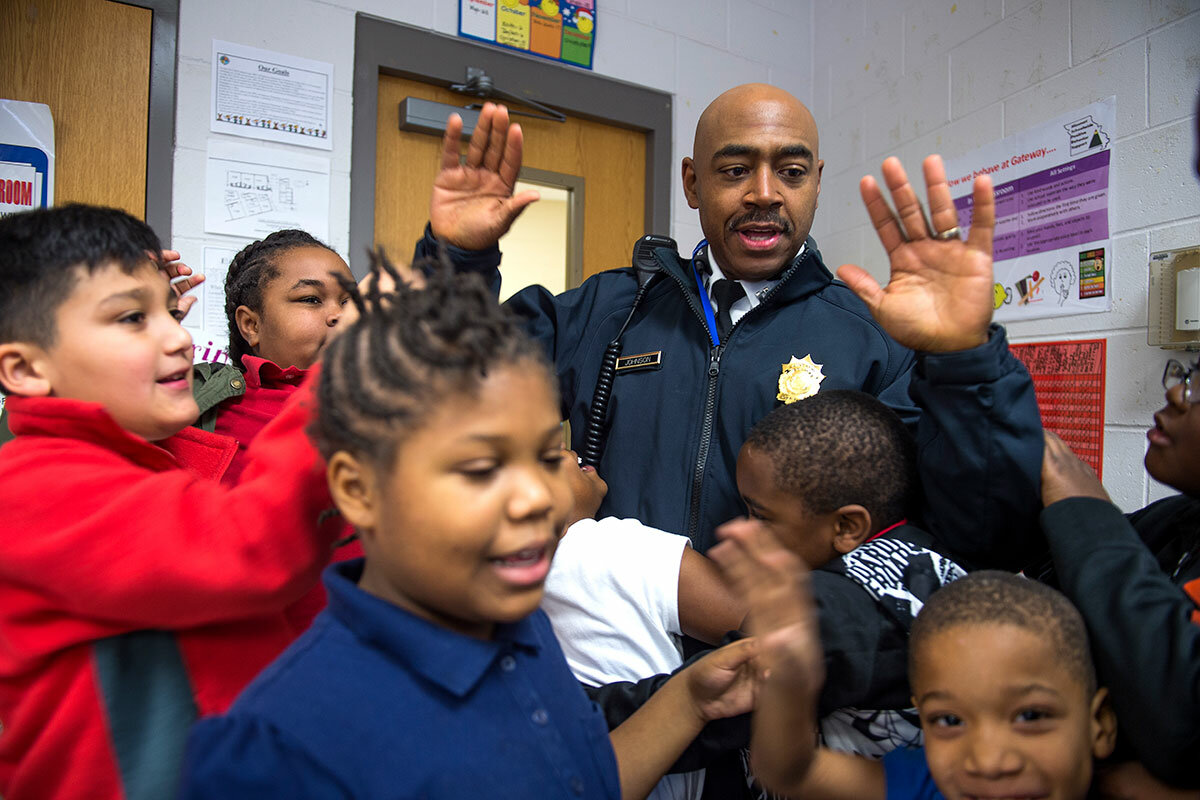

Perri Johnson, who is an African-American police captain and participant in Touchy Topics Tuesday, is now planning to start a similar group to promote understanding between black officers and black residents.

He was struck by an African-American adult who confessed to him that he was afraid of law enforcement. The 2015 Ferguson Commission report, which examined the root causes of the Brown shooting and subsequent protests, cited research that showed a big gap in trust of police – only 37 percent of black Americans trust officers versus 59 percent of white Americans.

“I had someone come to me and say, ‘Well, you know what, as a black officer, you need to quit your job [as a form of protest] and turn your badge in,’ ” says Mr. Johnson. “Well, that doesn’t make any sense.... There are a lot of people within the department that want to make change.”

Johnson, who is deputy commander of the police department’s Bureau of Community Outreach, says 90 percent of people in the black and white communities are good. The same goes for police officers. “We have to help each other with our 10 percents,” says Johnson.

The officer is also helping to break down stereotypes within the department, teaching required classes on racial profiling. Though blacks make up 47 percent of the population in St. Louis, they account for only 29 percent of the police force today – and the disparity grows starker in the higher echelons of the force. The Ethical Society of Police, the city’s black police union, found in a 2016 report that among many of the most prestigious units, 80 to 100 percent of officers were white. While expressing support for the majority of officers, the report described systemic biases along racial lines.

“As with any organization, we can always do better,” says Ed Clark, president of the St. Louis Police Officers Association, the main police union. “We want everyone to feel like you got a fair shot at promotion, or a special job, or even getting hired.” But he adds that no one has ever come to him and said they believed they hadn’t gotten a job because they were a minority – though some white officers have told him they got passed over in favor of less-qualified African-Americans.

Often overlooked in the racially charged conversation about policing is the increasingly dangerous environment in which the city’s police force operates. Since 2011, incidents of murder and non-negligent manslaughter have risen 66 percent in the city, according to FBI statistics. And that affects officers – white and black – not only as cops but as residents.

“We are part of the community,” says Mr. Clark, who – like many officers – lives within city limits. “We don’t want to worry about our families when we’re at work.... We want the crime to go down. That’s what I think everyone is working for.”

St. Louis has a mixed legacy when it comes to racial issues. Missouri entered the Union as a slave state, and it rejected Dred Scott’s quest to win his freedom through the courts. As recently as 1948, Missouri’s highest tribunal upheld a lawsuit that banned a black family from occupying a home in a white St. Louis neighborhood – a decision later overturned by the US Supreme Court.

Yet civil rights activists in Missouri were also among the first to push for the desegregation of buses, lunch counters, and other public places. Despite these pioneering efforts, however, St. Louis today ranks as the fifth-most-segregated city in the nation.

“Often we want to, and a lot of white people want to, jump to healing without really reckoning with the history and the mistrust and the deep hurt,” says David Dwight, a member of Forward Through Ferguson, a group created to implement the 189 recommendations of the Ferguson Commission. “And you have to deal with that first, before you can get to healing.”

An 18-year gap in life expectancy exists between blacks and whites in neighborhoods here just 10 miles apart. Close to six times as many black children live in poverty in St. Louis County as white children. The state headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan lies just an hour’s drive from the city.

In the wake of Ferguson, a US Department of Justice investigation revealed that the largely white city government was deriving millions of dollars in revenue from mainly poor, black citizens stopped for minor traffic violations. Because of their inability to pay the initial fine, many of those ticketed spent weeks or months moving in and out of jails, navigating court appearances, and shelling out fees, fines, and bail payments.

It’s a pattern that lawyers say remains common – and deleterious – across St. Louis County. “We’re not getting public safety by fining or jailing or citing folks whose contact with the legal system is a result of their poverty,” says Thomas Harvey, executive director of the legal advocacy group ArchCity Defenders.

Yet many changes have taken place in the city since 2014. In April, Lyda Krewson became St. Louis’s first female mayor. She appointed an African-American judge as her director of public safety, which oversees the police department. She has also pulled together a citizen advisory committee to help find a new police chief.

In November 2016, Kim Gardner became the first African-American to be elected circuit attorney, the office that prosecutes state-level criminal cases in St. Louis, on the promise of trying to restore trust in the criminal justice system.

One of her top concerns is how to investigate police shootings. Currently, a Force Investigation Unit within the police department takes the lead on such inquiries. But after Stockley’s acquittal, Ms. Gardner asked the city’s Board of Aldermen for $1.3 million to create a unit that would become the lead investigative body. She argued that her office had not been able to access key interviews and obtain relevant documents – a charge the FIU disputed.

“At what time do we think that a body who is investigating one of [its] own is appropriate?” asks Gardner. “It deteriorates the public trust.”

Other changes have come from the courts. In November, a federal judge ordered the city to refrain from using chemical agents such as pepper spray and other tactics against people engaged in “expressive, nonviolent activity.”

Yet the police have their supporters, too. Just days before the judge’s ruling, the city voted overwhelmingly to pass Proposition P, which gave the police department more funding – a move Clark, of the main police union, says reflects confidence in the men and women in blue.

Ultimately, some residents believe the best way to improve race relations in the city isn’t through street protests but the ballot box. Dellena Jones, a hair salon owner in Ferguson who is still paying off loans for damage caused by the riots, holds classes on how to fight discrimination through government channels. “There’s other ways of doing things, like voting,” says Ms. Jones. “You can’t say the system is flawed if you don’t work the system.”

A few activists are going even further: They’re running for office themselves. One, former battle rapper Bruce Franks Jr., is now a state legislator. Cori Bush, a nurse and pastor who took her ministry to the streets of Ferguson, is vying for a seat in Congress in 2018. Ms. Bush decided to run after watching elected officials remain silent or visit the protests just for a photo op.

“There have to be people in positions of power that actually love the people, that have a heart for the people, and that the people actually love and respect as well,” she says.

But social change doesn’t come through legislative action alone. Some of it comes through private conversations and shifts in attitudes. Sullivan, the suburban mother, is using the post-Ferguson ferment as a teaching moment for her children. She’s also been talking with friends about what she’s learning – though it hasn’t always been well received.

When she shared on Facebook her account of being arrested during a demonstration, an account that was widely circulated, some people accused her of embellishing the story. And a few longtime friendships have flagged as Sullivan has taken to the streets to promote racial equality and push for fairer police practices.

Yet she seems committed to her new crusade to foster change, even if it means sacrificing nights at the gym and occasional reading time with her children. “I don’t think white people can place all of the burden of protest and speaking up and educating and changing hearts and minds and policy ... on the people who are being oppressed by our white racist systems,” she says, sitting at her dining room table. “That’s our work.”

Morocco press freedom slips, and social media fills the gap

While the Monitor focuses on progress, we have to be careful to avoid rose-colored glasses. What’s going on in Morocco is a good example of looking beneath a seeming “good news” story to better judge whether the progress is real.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Jackie Spinner Correspondent

Last year, in a move Morocco heralded as a major step toward a free press, the country overhauled its speech and press laws. But as a Human Rights Watch report noted, Morocco’s penal code undercuts the new laws. The judiciary hands out prison sentences for reporting that it says has harmed Islam, king, or country, leaving little room for critical coverage of important issues. The clampdown has pushed many journalists to practice self-censorship. And that, along with financial disincentives for the press to publish stories critical of the royal family, has eroded trust in the media, pushing news-hungry Moroccans to look elsewhere. The thinking behind this trend is “crazy and very dangerous. People have to go to Facebook to know what is going on in Morocco,” says a founder of a now defunct news magazine who has left the country. “I can’t trust anything I read in Morocco,” says an English interpreter who has worked with foreign journalists. “For anything to change, for media integrity, it’s going to be the job of civil society,” he says. “Journalism in Morocco needs people willing to support it.”

Morocco press freedom slips, and social media fills the gap

For David Alvarado, a Spanish journalist who has been covering North Africa for more than a decade, the real indication of how free journalists are to report in Morocco is which government ministry is watching most closely.

Officially, it’s the Ministry of Communications that issues press cards and can expel journalists or ban them from working here, says Mr. Alvarado, the former North African correspondent for Spanish-language CNN.

But in the past several years, he adds, the powerful Interior Ministry, responsible for national security, has been keeping tabs on him, calling to let him know that their agents saw him talking to people they didn’t like.

“We live in a democracy,” Alvarado says in his tidy office in the capital, where he runs a media-consulting business. “We are free to vote in the election. But the regime restricts many things it doesn’t want.”

Last year, Morocco overhauled its speech and press laws, a move the country heralded as a major step toward a free press. The intent was to decriminalize all speech that does not incite violence.

But as a Human Rights Watch report noted, Morocco’s penal code undercuts the new laws. The judiciary hands out prison sentences for reporting it deems harmful to Islam, the king, or the country, which doesn’t leave much room for critical coverage of the most influential issues in Morocco.

The threat of harassment, arrest, fines, and suspension – as well as economic pressure from advertisers close to the monarchy – has stifled coverage of the government and of citizen protests, including the mostly peaceful demonstrations that have taken place in Morocco’s northern Rif region since a fish seller was crushed to death last year in a garbage truck as he tried to retrieve fish confiscated by police.

Self-censorship

Hamid El Mahdaoui, founder and editor-in-chief of an Arabic-language online news website that has since been shut down, was sentenced to three months in prison after being arrested in July while covering a banned protest. Several other journalists also have been arrested and at least one foreign journalist was deported after his coverage was published. International human rights organizations have called for their release.

As a consequence of such measures, says Abdelmalek El Kadoussi, a communication professor in Meknes, the majority of journalists have taken to practicing self-censorship to avoid getting in trouble in the first place. And the list of stories they steer clear from has grown in recent years.

“Now, the king and the royal family are not the only official redlines,” says Professor El Kadooussi, who analyzed self-censorship in the Moroccan media from 2011-2016. “Other institutions like the military, the judiciary, and the security department are as well.”

In September, a video blogger was sentenced to 10 months in prison after publishing reports on police corruption, and last year seven journalists and educators were put on trial for organizing a Dutch-funded training on how citizens can use a secure mobile storytelling app. The trial has been repeatedly postponed for two years.

El Kadoussi says the consequence of the self-censorship is chilling for both journalists and for citizens. Traditional press readership has dwindled because the news outlets are simply not seen as credible sources of information. “Citizens have noticeably migrated to the digital space, which actually offers myriad less-constrained venues and platforms for criticism and investigation,” he says.

Discrediting the reporter

Journalists in Morocco had a brief honeymoon period after a young and comparatively progressive King Mohammed VI came to power in 1999 following the death of his iron-fisted father, King Hassan II. But it didn’t last. And when reporters started poking around the monarchy’s vast financial interests and exposing potential corruption or writing about the slow pace of change, they were quickly shut down.

In recent years, when the Ministry of Communication doesn’t like a story in the press, it seeks to discredit the reporter by leaking information about the journalist to other media, according to journalists and free press advocates interviewed for this article.

“What is happening in Morocco is they are pushing any kind of [critical reporting and discussion] to the social media,” says Aboubakr Jamaï, co-founder of the Moroccan news magazine Le Journal, which closed in 2010. “This fallacy of thinking is crazy and very dangerous. People have to go to Facebook to know what is going on in Morocco. They can’t read or watch the TV station to know what is going on.”

The problem is exacerbated by how media are funded and supported in Morocco. Businesses with ties to the monarchy control the advertising dollars that fund the news outlets. When a news outlet publishes content that is considered unfavorable or critical of the government, advertisers pull out. That financial carrot and stick is a powerful tool the government uses to control the press, says Maati Monjib, an outspoken Moroccan journalist and professor who went on a hunger strike in 2015 to protest declining press freedoms in the country.

Le Journal was stymied by lawsuits and an advertising boycott resulting from its critical reporting of the government, and Mr. Jamaï ultimately left the country. In a Skype interview, Jamaï, now the dean of a business and international-relations school in France, says he could no longer promise funders that he could move toward a sustainable business model because of economic pressures from the government. “There is no ability of the press to hold our elites accountable,” he says.

Media links to royal family

That financial pressure was highlighted by the findings of a Morocco media-ownership survey released late last month by Reporters Without Borders. It found that the royal family was the leading media owner in Morocco. Nine of the 36 most influential media companies in the county are linked to the government or royal family, it found. Advertising dollars, which fund media operations, are directed to these companies.

“We don’t have clear criteria on how this advertisement is distributed, especially when you see the media receiving the money,” says Yasmine Kacha, the North Africa director for Reporters Without Borders. Advertisers aren’t drawn to the most popular or circulated media but rather to the outlets that offer the most favorable coverage of the kingdom, she says. “It is given to media that is close to the Moroccan ministers. So this is where it becomes a press freedom issue.”

Only 17 of the 46 media companies contacted for the survey, which was conducted with Moroccan Le Desk, a subscriber-based news outlet, agreed to share information about their ownership, Ms. Kacha says. Although Moroccan law requires media companies to register with the government, information in the commercial registry was missing or not updated.

That has meant shadowy and often unpredictable treatment of journalists.

Foreign reporters or those who publish in English often have an easier time, although many still carefully write and produce around sensitive issues like the Western Sahara.

Alvarado, who has been living in Morocco since 2003, published a book last month on the Rif protests and has reported from the mountainous region without incident while covering the movement known as Hirak. He isn’t reporting from the Rif for the first time, he notes. “I worked on many subjects in many other regions and countries in the Maghreb,” he says, referring to the North African region. “The good ones and the worst ones. I think I'm respected by this.”

'I'm very discreet, which helps'

Moroccan freelance journalist Aida Alami, who went to journalism school at Columbia University in the United States and writes for Bloomberg and The New York Times, among other publications, also is largely left alone.

Ms. Alami doesn’t shy away from news reports that could embarrass Morocco, which carefully manages the image it portrays to the West. A few weeks ago, she wrote a story for The New York Times about a stampede during a food distribution in Marrakesh that left 15 dead. She’s also written about the Rif protests for the the Times and for Al Jazeera.

She says her reporting has been factual and doesn't attempt to advocate, which is one of the reasons she isn’t bothered. “I’m very discreet, which helps,” she says. “I’m not trying to brand myself as an anti-Morocco journalist.”

Morocco also does not have financial leverage over The New York Times in the way that it does for publications published in the kingdom. The majority of Moroccan news consumers don’t see the critical coverage that appears outside of the country.

“I can’t trust anything I read in Morocco,” says Achraf El Bahi, an English translator who has worked with foreign journalists and other organizations.

In spite of that and maybe because of it, Mr. El Bahi sees opportunity. He is launching an English-language magazine from Rabat next year. He is well aware that pressures from the government can make or break a new media outlet, he says. His magazine will focus on culture and not venture into politics. Nonetheless, he knows it won’t be easy, he says over tea one afternoon near the modern art museum named after King Mohammed VI.

“For anything to change, for media integrity, it’s going to be the job of civil society,” El Bahi says. “Journalism in Morocco needs people willing to support it.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

As San Antonio’s 300th nears, some Texas history gets a rethink

We know history helps define our sense of who we are. And Texas has never lacked confidence in its own identity. But San Antonio’s anniversary offers a glimpse of a different Texas.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

History is normally written by the victors, to the exclusion of other groups. Generations of Texans have been schooled in heroic tales of white male settlers taming a wild frontier and finding oil deposits. That simplistic story has been challenged in recent decades by historians and the descendants of other immigrants and indigenous groups, fueling a lively debate that will resonate this year in San Antonio, a city founded in 1718 by Spanish settlers. The tricentennial celebrations are an occasion to reflect on whose history is taught in schools in Texas. “I want to see ... what they talk about, see if they’re going to keep our history in there,” says Pedro Huizar, a retired sheet-metal worker who traces his family tree to an 18th-century Spanish craftsman. Visitors to San Antonio can see his ancestor’s handiwork in the Rose Window at Mission San José, a popular historical attraction.

As San Antonio’s 300th nears, some Texas history gets a rethink

Growing up, Vincent Huizar never took much interest in Texas history. He flunked history class in high school, and while he knew his family had lived in the San Antonio area for centuries, he didn’t inquire any further until his son had children.

The third grandchild was born with light skin, light brown hair and hazel eyes, says Mr. Huizar, who has leathery brown skin and dark eyes. His son turned to him and asked a simple question: “Dad, what are we?”

The question launched a 17-year genealogical hunt that led Huizar to discover that he is a sixth-generation descendant of Pedro Huízar, a surveyor and craftsman from Spain who is credited by most for sculpting the iconic Rose Window at Mission San José, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The origins of the 18th-century Rose Window are still being debated. But Huizar’s journey into his family roots reflects a much larger issue for Texans: How to add nuance and a multiplicity of perspectives to a historical narrative that has long been romanticized and oversimplified.

“Jim Bowie and Davy Crockett and all those people weren’t part of me,” Huizar says. “I wasn’t descendants of them. I was a descendant of the other people they were coming in and killing and getting rid of.”

As San Antonio gears up to celebrate its 300th anniversary this year, commemorating the city’s founding in 1718 by Spanish explorers, historians in Texas are trying to broaden how the state memorializes its history.

“It’s very difficult to understand how things are today without looking to the past and how we got here and the experience of our ancestors,” says Brett Derbes, managing editor of the handbook of Texas.. “No one wants to feel they’re not represented in that history.”

For generations, a romanticized vision of Texas history was of white male settlers taming a wilderness; of James Bowie and Davy Crockett falling at the Alamo; of cowboys herding cattle across the plains; and of gushing oil wells. That vision largely left out Native Americans, women, African-Americans, and other groups.

Texas is far from unique in that sense, as evinced by roiling battles over the removal of Confederate monuments in the South and revisionist accounts of the rebels’ cause. Still, in recent years the state has taken steps to promote more diverse and unvarnished perspectives on its history, even as conservatives have pushed back on school textbooks.

More than 'cowboys and oil'

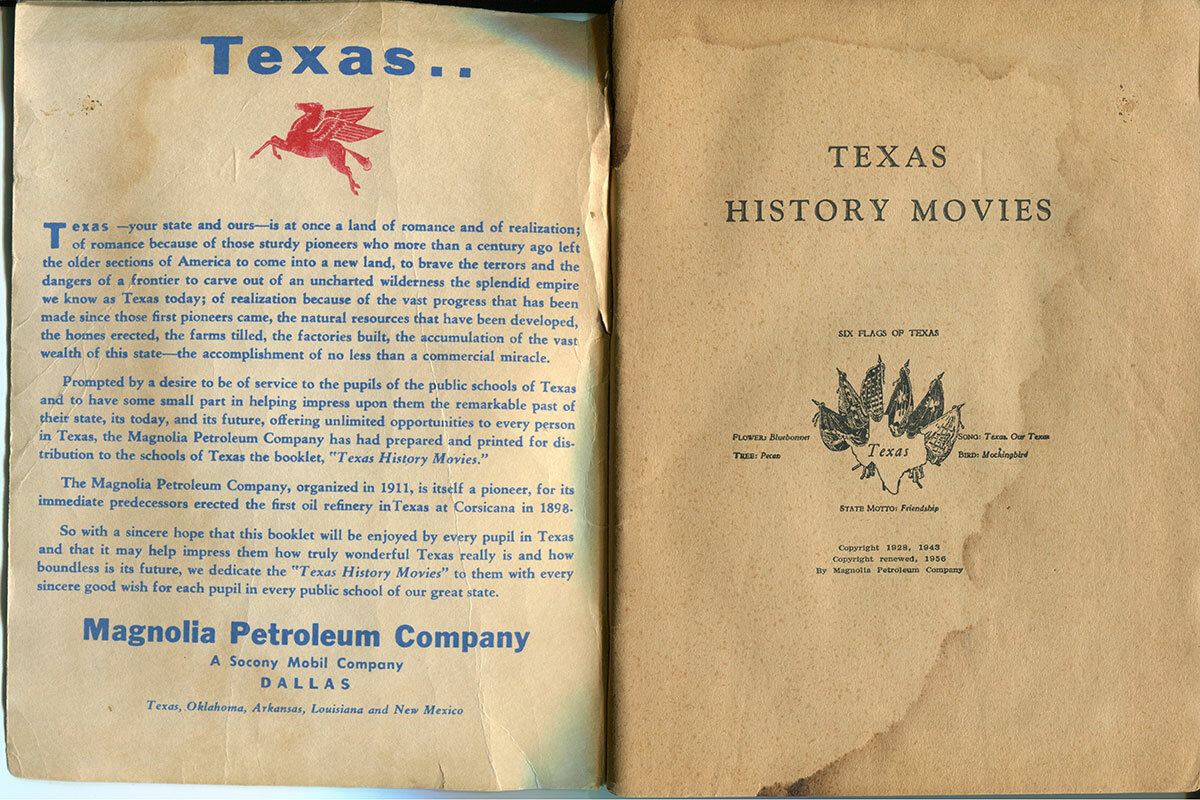

Until the 1960s, students in Texas learned from an illustrated book called “Texas History Movies.” Sponsored by Mobil Oil, the book was criticized by historians for its racial stereotypes and biases. The most popular adult book on Texas history, T.R. Fehrenbach’s 1968 epic “Lone Star,” told from the perspective of white male settlers, has been challenged by more academically rigorous texts.

As a high school student in 1960s Houston, for example, Michael Hurd – who now directs the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture at Prairie View A&M University – describes his education in African-American Texas history as: “There was slavery, there was emancipation, and here we are.”

“Everything was focused on slavery, but there was nothing in regards to any other aspects of the black experience in Texas, like business, athletics, entertainment,” says Mr. Hurd, who is black.

As for Mexican-Americans and Tejanos, whose families have lived in Texas since it was a 17th-century Spanish colony, their roots were also obscured.

Armando C. Alonzo, an associate professor of history at Texas A&M University, went to high school in a small town near the US-Mexico border.

“We weren’t even taught really the [state’s] Spanish past,” he says. “The typical history books made Mexican-American people to have no history, [that we] came as immigrants in the 1910 [Mexican] revolution.”

A broader view

In 1968, San Antonio helped to birth a broader view of the past when it hosted the World’s Fair. In true Texas fashion, the state wanted its own pavilion in addition to a United States one, and the result was the largest pavilion at the fair, an inverted pyramid indoors divided into sections for each of the ethnic groups that settled Texas, including Native Americans and the Spanish. After the fair ended, the pavilion remained open as the Institute of Texan Cultures.

Another example is the Handbook of Texas, an official chronicle of the state’s history. The TSHA began publishing it in the 1950s and focused on “those popular Texas topics” like Sam Houston, Stephen F. Austin and the doomed siege of the Alamo, says Mr. Derbes, the managing editor of the Handbook.

“In the 1980s there was a huge effort to expand” it, he adds, “to include as many perspectives as possible.”

That effort has seen the publication of new editions of the Handbook – all also published online – focusing on African-Americans' Texas history, Tejano Texas history, and women in Texas history, among others.

Darker historical events have also been surfaced. The Handbook now details the “Cart War,” an 1857 conflict that saw Anglo traders attack, kill, and steal from their more successful Tejano competitors. It also describes the state’s long history of lynchings of African-Americans.

'I had to teach myself'

Some of the historians who challenge the popular narrative say they had to fashion their own versions of local history.

Dr. Alonzo didn’t formally study history until he was a grad student; he credits his inspiration to the Chicano movement of the 1960s. “I had an interest, but at that moment, 1970 … universities didn’t have the resources to teach it,” he adds. “No one was there to teach me, so I basically had to teach myself.”

Professor Hurd, meanwhile, says he learned about black history by reading black-owned magazines and newspapers like Ebony, Jet, the Chicago Defender, and the Houston Informer.

“There’s so much more of it now since I started this journey after I graduated high school,” he adds. “I would say from the 1980s – and maybe just the 1990s – that some of that scholarship has come out.”

Signs of progress and empathy

Broadening the study of Texas history remains “a work in progress,” however, according to Sarah Gould, at the Institute of Texan Cultures at the University of Texas, San Antonio.

The Texas Board of Education was criticized in 2010 for approving curriculum standards with a distinctly conservative political bent: a positive presentation of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade; prominent coverage of President Reagan; and material on the “unintended consequences” of Title IX, affirmative action, and the Great Society. More recently, the board rejected two proposed Mexican-American studies textbooks in the past year, though it has said that it’s open to such studies, which have been adopted in other states.

The Tricentennial is also drawing more attention to overlooked aspects of traditional Texas history – including how Juan N. Seguin, a Tejano hero of the Texas Revolution, fled to Mexico decades later after threats of violence from Anglo settlers.

Huizar, a retired sheet-metal worker who lives in San Antonio, remains skeptical of what the city’s 2018 celebration will bring.

“I want to see what their version is going to come out, what they talk about, see if they’re going to keep our history in there,” he says.

Incorporating these different perspectives into Texas history could have benefits beyond making people like Huizar feel more included in the culture and fabric of the state, say historians.

“I think we all have to try our best and open our minds to thinking about history as a multi-perspective event,” says Dr. Gould.

“When you show [people] there are multiple perspectives it allows them to better imagine themselves in those situations, and it also teaches them to be empathetic,” she adds. “I don’t think it would be too much to ask we bring that concept of empathy into the teaching of history.”

Correction: Prof. Sarah Gould is at the Institute of Texan Cultures at the University of Texas, San Antonio.

Difference-maker

To boost young readers, digital books in their native tongues

For one literacy nonprofit, doing good means listening to what communities actually need most. In Rwanda, that means books in English are good. Books in Kinyarwanda are better.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The effort to boost literacy around the world is getting a hand from a New York-based organization called Library for All. The nonprofit provides young readers in developing countries with digital books in their mother tongues. Founded in 2012, it currently exists in five countries: Rwanda, Congo, Haiti, Cambodia, and Mongolia. The books are read on devices that people living in poverty in each region are most likely to have access to, such as low-cost phones or tablets. Children benefit from reading and learning in their strongest language, research suggests. But the initiative has another aim as well: to give young readers access to material that helps build their sense of identity. That’s one reason Library for All recruits local volunteers to write books. “Our mission is to make knowledge accessible to all equally, but it’s also to ensure that children have the ability to learn, dream, and aspire to lift themselves out of poverty,” says Tanyella Evans, cofounder and chief executive officer. “Part of that is having that dignity, that self-confidence – to see that you can be the protagonist of your own story.”

To boost young readers, digital books in their native tongues

For some students at Umubano Primary School, located just outside Kigali, Rwanda, being bilingual is a necessity.

At Umubano, classes are taught in English – but at the end of the day, a significant number of students go home to parents who speak only Kinyarwanda. Although the school offers some lessons in Kinyarwanda, physical learning materials in the language aren’t easy to come by. The number of books available in Kinyarwanda is limited, says educator Amy Barnecutt, and the few owned by the school tend to be flimsy and in poor condition.

That’s where Library for All, a nonprofit organization that provides young readers in developing countries with digital books in their mother tongue, has come in. For the past two years, Umubano has partnered with Library for All so students can access a robust cloud-based library filled with culturally relevant books in Kinyarwanda and other languages.

A goal of Library for All is to boost literacy in these regions, as research suggests that children benefit from reading and learning in their strongest language. But the initiative has another aim as well: to give young readers access to material that they can relate to and that helps build their sense of identity. This is one reason that Library for All recruits local volunteers to write books.

“Our mission is to make knowledge accessible to all equally, but it’s also to ensure that children have the ability to learn, dream, and aspire to lift themselves out of poverty,” says Tanyella Evans, cofounder and chief executive officer of Library for All, which is based in New York. “Part of that is having that dignity, that self-confidence – to see that you can be the protagonist of your own story.”

Library for All, founded in 2012 by Ms. Evans and Rebecca McDonald, currently exists in five countries: Rwanda, Congo, Haiti, Cambodia, and Mongolia. The organization optimizes its library for the electronic devices that people living in poverty in each region are most likely to have access to, such as low-cost phones or tablets.

Evans recalls one student in Haiti, a former victim of child slavery, who had returned to school after years out of the classroom. At first, she says, he couldn’t read out loud because of low self-esteem and reading-level deficiency. But after a few months of taking part in a program that incorporated Library for All’s digital library, he was “so excited” to get up in front of the class and read for his peers.

“Part of that was just reading in a language that was familiar to him – the language he speaks on the playground with his friends and at home with his family,” Evans says.

Research suggests there are numerous advantages to children learning in their mother tongue. A frequently cited 2008 UNESCO report found that children enrolled in mother tongue-based bilingual education programs performed better academically than students who learned only in their second language. They were also more likely to participate actively in the learning process and to feel confident about learning.

Storybooks are an important part of building literacy early on, says Carol Benson, associate professor of international and comparative education at Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York. And, she says, “when [children] are learning literacy for the first time, it’s easiest and most efficient for them to do that in their strongest language.”

Benefits all around

At Umubano Primary School, offering books in Kinyarwanda has not only aided students in developing language and comprehension skills, notes Ms. Barnecutt, country director for A Partner in Education, the nongovernmental organization that supports Umubano. It’s also made life easier for educators.

“As a teacher, allowing children to learn in their mother tongue helps to assess the true knowledge of the learners without the added complexity of foreign language translation,” she says.

Shortly after launching a pilot program in Cambodia last year, Library for All discovered one major challenge in bringing culturally relevant reading materials to the area’s children in their mother tongue: There just weren’t that many books to choose from.

Library for All’s digital library contained about 50 children’s books in the Khmer language. And so, Evans says, “we started thinking, ‘How can we create content locally in the community in a cost-effective and efficient way?’ ”

The answer: local writers’ workshops.

Earlier this year, Library for All piloted a series of workshops in Haiti, funded through a grant from the United States Agency for International Development, for volunteers from the region to write curriculum-appropriate books in Haitian Creole. Using software that keeps writers on track by detecting the difficulty of words and phrases, the volunteers created 109 books over the course of two weeks.

‘Valorizing the home culture’

Books can be “really useful for building identity and self-esteem, especially if girls and boys are both represented and culturally appropriate topics are taken up,” Professor Benson says. This makes books penned by local authors all the more valuable.

“It’s not just a matter of translating materials,” Benson says. “It’s a matter of valorizing the home culture and language of the learners.”

• Staff writer Ben Rosen contributed to this report.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Iran boils again

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Nearly a decade has passed since Iran’s so-called Green Movement produced a level of public protest – then over the result of disputed elections – similar to what we are seeing today. Those protests burned themselves out. What is different today, as outrage grows over an array of grievances, is the large number of young Iranians who are not only aware of what’s happening in the outside world but also able to share their feelings with others, globally and inside Iran, through social media. The protests show how Iranians continue to chafe against a theocratic government that ill fits a country that contains an educated and sizable middle class, as well as a large number of youths eager for jobs and hopes for a better life. The top may not yet blow off the kettle in Iran. But the pressure for reform that keeps building will never be vented without a transition to a freer society.

Iran boils again

The protests that leapt across Iran last week, and intensified over the weekend, may share one thing with the recent fires in southern California: No one knows exactly where they will go or how long they will last.

Conservative opponents of the more moderate Iranian President Hassan Rouhani may have lit the match by encouraging antigovernment demonstrations. But they have quickly morphed into outrage over a wide array of grievances, from the price of eggs (a symbol of wider frustrations with the struggling economy) to a more general disenchantment with life under a strict form of Islamic rule that has curtailed open dialogue for nearly four decades.

Iranians are also very aware that the regime has been aiding various political and insurgent groups abroad, and even President Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime in Syria, while they suffer at home. The chat “Leave Syria, remember us,” has been heard.

At this writing, hundreds of protesters reportedly have been jailed and at least 21 people killed. Mr. Rouhani has said that “the people are completely free to make criticism and even protest,” but he has also indicated there will be limits on what is allowed.

International calls for the protests to remain peaceful, for human rights to be respected, and for the government to take a restrained approach in its response seem appropriate.

President Trump tweeted, “The U.S. is watching.” But the regime should be given no excuse to claim (as supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei already has) that foreign powers are behind the demonstrations, which clearly are the result of myriad domestic frustrations, not foreign intervention.

Nearly a decade has passed since 2009 when Iran’s so-called Green Movement produced a similar level of public protest, in that case over the result of disputed elections. Those protests burned themselves out without effecting any real change.

What is different today is the large number of Iranians carrying smartphones, perhaps as many as 48 million in a country of 80 million people. They are not only able to learn about what’s happening in the outside world, they are also using apps such as Instagram and Telegram to share their feelings with others inside Iran. The government has put restrictions on those services. Iranians will have to find other ways to communicate.

It remains to be seen whether the government will crack down more harshly. But the protests show how Iranians continue to chafe against a theocratic government that ill fits a country with an educated and sizable middle class, as well as a large number of youths eager for jobs and hopes for a better life.

The top may not blow off the kettle during this outbreak of protests. But the pressure for reform that keeps building within Iran will never be vented without a transition to a freer society.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The job will follow

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Bruce Clark

Fear is the biggest challenge for people who find themselves in involuntary job transitions. As the former owner and operator of an outplacement firm, contributor Bruce Clark would try to get clients to understand that their job wasn’t their identity. While he didn’t say this to clients directly, he knew in his heart that man’s identity comes from God. It’s an idea he learned about through his study of Christian Science. Mr. Clark discovered that working with clients to identify the qualities they bring to their work and their lives helps them approach the job-search process from a higher perspective. He found that people would begin to get job offers when they became comfortable with this quality-constituted view of identity. Sometimes we adopt labels that limit us, but those labels don’t change who we are. Underneath, we’re still expressions of God. Being that expression is our real employment. That’s the job God has “hired” us to do – forever.

The job will follow

Fear is the biggest challenge for people who find themselves in involuntary job transitions. Being out of work can feel like a degrading experience, especially if you’re the sole or primary breadwinner for the family.

As the former owner and operator of an outplacement firm, I would try to get clients to understand that their job wasn’t their identity. Therefore, being jobless wasn’t their identity either. I would go through several exercises with each person, identifying the qualities he or she brings both to work and to everyday experience. Then we would gather that information together and recognize it as the expression of that person’s individual identity.

I didn’t say this to clients, but I believe that our identity comes from God. It’s an idea I’ve learned about in my study of Christian Science. The more we recognize our oneness with God’s infinite intelligence and ability, the more we progress in our lives. I never talked about these points explicitly at the office, but I feel this spiritual perspective guided me in my work. I prayed not to make judgments based on someone’s appearance or on whatever the company referring the person may have told me about him or her. Instead, I tried to see God’s likeness when that person came through the door.

One interesting result of this is that I rarely had a sense of how old people were – and I didn’t try to figure it out. I honestly don’t believe age can keep a person from doing the work he or she is meant to do.

Each of us is valuable and has a place in God’s plan. Each of us is needed and will be able to fulfill whatever is required of us. We should expect our work to be fulfilling both in its reward and in its potential for personal growth. Jesus said, “The labourer is worthy of his hire” (Luke 10:7), so I encouraged job seekers to expect an outcome that’s worthy of their abilities.

Working with clients to identify the qualities they bring to their work and their lives helps them approach the job-search process from a higher perspective. It also helps them avoid getting caught up in the conventional wisdom that says you can be too young or too old to find a job easily. Or that women find jobs faster than men but don’t get paid as much.

I found that people would begin to get job offers when they became comfortable with this quality-constituted view of identity. Frequently, things people thought would be impossible for them to do turned out to be very possible. Opportunities they didn’t recognize early on suddenly become clear to them.

Expressing God is innate to our being. Sometimes we get in the way of that by adopting labels that limit us, but those labels don’t change who we are. Underneath, we’re still expressions of God. Being that expression is our real employment. That’s the job God has “hired” us to do – forever.

Adapted from an article in the October 2001 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

Their yearly dust-off

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Tomorrow, we'll look at the question that just won't go away. To do anything of substance – including passing a budget – America's two political parties will have to find areas in which they agree. But with political forces swirling ever more strongly toward polarization and deadlock, will they have enough incentive to do that?