What happens to drug-crime policing when you take away the stick? A tough-on-crime state with swelling prison rolls is about to find out.

In 2016, voters here approved a closely fought ballot initiative to reclassify drug possession and minor thefts as misdemeanors. The idea was to steer nonviolent drug offenders who stole for their habit away from prison and into treatment programs. The reform appealed both to voters here alarmed at rising prison costs – Oklahoma’s rate of incarceration is second only to Louisiana’s – and those who saw locking up nonviolent addicts as futile.

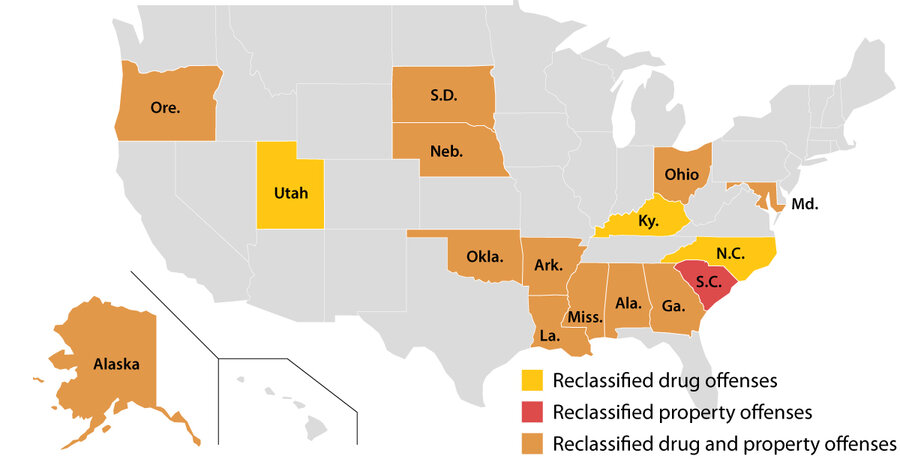

The reform passed over the opposition of law-enforcement agencies and public prosecutors, and was rejected in many rural counties. But it mirrored efforts by other states, including Louisiana, looking for ways to end mass incarceration, even as the Trump administration has rowed in the opposite direction, urging federal prosecutors to seek longer prison sentences.

It makes sense for states to reform drug sentencing since punitive laws don’t appear to curb drug abuse, says Adam Gelb, a criminal-justice expert at The Pew Charitable Trusts. “Locking up more drug offenders increases punishment, and if that’s the goal, then it works. If it’s about improving public health and safety, the numbers don’t back that up,” he says.

Across the country, the number of people in state and federal prisons fell in 2016 to about 1.5 million, down from 1.6 million in 2009 and the third straight year of decline, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Debate over reform's efficacy

Oklahoma’s reclassification took effect last July and the debate over its efficacy remains potent: Republican state lawmakers tried unsuccessfully to dilute the changes and may try again in this year’s session. For their part, reformers are also trying to advance criminal justice bills.

In Oklahoma County, the largest jurisdiction, the changes are apparent. Last year, prosecutors filed the lowest number of felony cases since 2011, while the number of misdemeanors rose by 37 percent from the previous year. This reversal was seen across the state, with a 26 percent drop in felonies on court dockets.

So what happens when drug offenses no longer lead to felony charges? Do addicts avoid prison and get treated for substance abuse? Or simply pay a fine and walk away, only to reoffend again?

Capt. Adam Flowers, a detective in the Sheriff’s Office of Canadian County, which straddles Oklahoma City’s suburbs, says it’s the latter. The ballot measure, while well-intentioned, is tying the hands of officers who deal with addicts and petty criminals on a daily basis. “If it’s just a misdemeanor and you’re not going to prison, it takes the teeth out of what we’re going to do,” he says.

Tough sentences for drug-related offenses, mostly methamphetamine, have helped to crowd Oklahoman prisons, including those for women, whose rate of incarceration is the highest in the United States. Nearly one-third of all state prison inmates were convicted of drug offenses, according to a 2017 report by a state task force on justice reform that proposed major changes in sentencing, probation, and other aspects.

For meth addicts who commit nonviolent crimes, treatment is clearly a better and cheaper option, says Mark Woodward, a public-information officer at the Oklahoma Board of Narcotics. It costs about $19,000 a year to keep an offender in a state prison in Oklahoma, compared with $5,000 for a community-based rehabilitation program.

But like Captain Flowers, Mr. Woodward is concerned that the lighter touch for low-level drug crimes will reduce participation in substance-abuse programs. “We’re not locking them up or giving them an incentive to go to treatment, or to stay in treatment,” he says.

Treatment still an option

Reformers say that courts are still directing addicts into treatment and that prosecutors have leverage to cut deals, even with a reduction in felony charges. “The stick is not being taken away. It’s perhaps bit smaller, but the research is clear that it is still of sufficient size,” says Mr. Gelb, who directs Pew’s Public Safety Performance Project.

Drug distribution and trafficking remain felonies in Oklahoma; the same applies to property crimes where the value exceeds $1,000. And felons convicted of dealing drugs face stiff penalties: The average sentence is more than eight years.

Moreover, misdemeanors for drug and property offenses can result in jail time, and that creates an opportunity to seek treatment, says Ryan Gentzler, an analyst at the Oklahoma Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank in Tulsa.

“People who struggle with addiction are not long-term planners. Any arrest, any time behind bars, is going to weigh the same in their judgment,” he says. “Whether they decide to use drugs has very little to do with the amount of time they’re threatened with.”

Terry knows all about addiction – and treatment. Age 37, he has been using meth since he was a teenager. He blames it for his chaotic life and the 11 years he spent in prison for burglary. “It’s made my life a complete and living hell. There’s nothing good about it,” he says.

Terry is a scrawny six-footer with a scratchy brown beard and prison tattoos on his forearms. Last February, he was arrested in Oklahoma City on suspicion of selling meth and charged with a felony. In November, he received a 15-year suspended sentence under a plea agreement that sent him into rehab.

His first stop was The Recovery Center, a detox facility in Oklahoma City. It was his fourth attempt to get clean. The last time, he says, he completed 71 days of treatment, then within a week relapsed. “I went looking for it without even knowing that I was looking for it,” he says.

Earlier this month, Terry was transferred to a 90-day treatment center in McAlester. “I’m hoping to learn something. Treatment teaches you why you get high, the underlying reasons for doing what you do,” he says.

It’s a chance for Terry to break his addiction – and a condition of his sentence. Still, the idea of being sent to prison doesn’t faze him, since he’s done time before and says meth is easy to score inside. “I am my problem and methamphetamine is my solution,” he says.

Money saved, but skeptics question it

Voters in Oklahoma also approved an accompanying ballot measure that mandates that any money saved by imprisoning fewer people be spent on substance abuse and mental health. This funding mandate echoes a similar proposition passed in California in 2014, which last year redirected $103 million in grants from cost savings from lower imprisonment rates.

Oklahoma has cut the budget of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in three of the last four years. This has led to lower reimbursement rates for private drug-treatment centers and less incentive for these providers to expand services, says Jeff Dismukes, a department spokesman, who says the waitlist for publicly-funded substance abuse programs is currently about 500 people.

“You need to make sure that the treatment [for addiction] is available,” he says. “It’s about getting people to the right services. When you put people into the right services they get well.” Critics of Oklahoma’s reforms point out that California is reinvesting less money in rehabilitation than was promised by backers of the proposition. Oklahoma is to start calculating its savings starting in July.

Public prosecutors are skeptical about the promised savings. David Prater, district attorney for Oklahoma County, told The Oklahoman newspaper that he didn’t expect any savings because public safety agencies, including prisons, were so cash-strapped after years of cutbacks.

Last week, the Department of Corrections requested a budget increase of more than $1 billion, including $813 million to build two new prisons, one for women and one for men. Oklahoma already spends more than $500 million a year on its prisons.

Prosecutors have a financial incentive to push a punitive approach. For every felon on probation or parole, district attorneys receive a $40 a month supervision fee, says Susan Sharp, a sociologist at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. Similarly, sheriff’s offices prefer to move offenders from county jails, which come out of their budget, and into state prisons.

Out in Oklahoma’s rural panhandle, faith-based programs have shown success in turning around former drug users, says George Leach III, assistant district attorney for Texas County and three adjacent counties. The vast majority are users of meth, the illegal drug of choice in the US heartland and the leading cause of drug-related deaths in Oklahoma.

“Usually treatment doesn’t work the first time. By the time we do it twice, 50-60 percent of people we don’t see again,” he says.

Most meth addicts were sent to treatment while on probation for felony convictions, for which the bar is now set much higher. Mr. Leach worries that fewer will now go.

“The issue is not that they can’t get treatment. It’s that they don’t want it,” he says. To stay on meth “is easy. Going through 12 months of treatment is something else.”

Clarification: This article has been updated to reflect the Department of Corrections' total budget increase request.