- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for January 31, 2018

Americans haven’t associated Europe with dynamism in the past decade. That’s all the more reason they should take note of a bit of news from the continent: the European Union said Tuesday that the gross domestic product of both the EU and the eurozone jumped 2.5 percent in 2017, outpacing that of the United States. That’s its fastest growth rate in a decade. And helping to drive it was France, which just a year ago was in the throes of what looked like a populist revolt that would deliver the presidency to right-wing euroskeptic Marine Le Pen.

Instead, we now have President Emmanuel Macron and a country experiencing a distinct shift in its view of itself.

Sara Miller Llana, our Europe bureau chief, is tracking this new buoyancy. One analyst told her Mr. Macron is “the most proud European we’ve ever had in the Fifth Republic.” And an entrepreneur characterized his country, long known for workplace constraints, as full of "hustle."

This march didn’t start with Macron. And it's happening in the context of a global “synchronized recovery,” with unemployment falling and investment rising in all major economies. But his confidence in France’s ability to innovate and reform, combined with firm support for the “European project,” is catching on. Now, businesses are talking about shedding fear – and believing in the future.

Now, here are our five stories, which get us to think twice about accepted perspectives on everything from infrastructure to planet Earth.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

On US infrastructure, contention – and a hint of an opening?

Discussion of America's deteriorating bridges and roads quickly surfaces two things: sharp philosophical differences over how to fund fixes, and agreement on the urgency of the problem. Perhaps there's more common ground than appears on the surface.

Recently two scholars at the Brookings Institution, a think tank often associated with centrist Democrats, opined that the United States “is moving into an era where more of the agenda setting and funding [on infrastructure] are falling to local governments.” A key reason? Not because President Trump is pushing that idea, but because local governments are “especially attuned to local needs.” And both major parties agree the US has big holes to fill – or tunnels to dig – when it comes to upgrading roads, ports, and water systems. But they also have dueling philosophies. Democrats say more federal spending is vital. Mr. Trump hopes to accelerate the shift toward state or local funding. (He wants to generate $1.5 trillion in projects, but news reports say he wants to spend only $200 billion or so in federal money to get there.) Many constituencies, from governors to some labor unions, say in effect that both sides are right: Localities need to lead, but lots of them need federal help. For now, the partisan rift is a roadblock to any Trump building boom.

On US infrastructure, contention – and a hint of an opening?

Opening the second year of his presidency with an address to the nation, President Trump launched a long-awaited initiative on infrastructure that is both bipartisan in spirit – and highly contentious.

It’s common ground as a priority, because the need is as obvious and widespread as the nearest airports, bridges, or water mains. It’s contentious because of a rift over funding – partly over sheer dollar amounts, but also over the proper government role. While Mr. Trump pitches reliance on state and local governments, aided by private-sector partnerships, Democrats are pushing a much stronger role for federal funding.

That state-federal rift between the parties isn’t limited to this issue, of course. But it’s one that now threatens deal-making on a concern that in many ways should be ripe for congressional compromise.

The Trump plan, still not released in full detail, tilts toward the states at a time when infrastructure planning and funding have already been moving in that direction. But experts say the dueling visions could be a theme that persists as a source of tension, even as the realities of a “deferred maintenance” America push the parties toward action.

“A lot of this [state-level emphasis] is based on a phenomenon that's happening across the country, where states and cities and metro areas are raising their own taxes” to pay for infrastructure projects, says Robert Puentes, who heads the Eno Center for Transportation, a policy think tank in Washington.

The idea of localities taking a lead role in their own infrastructure is already well established, he says. But the challenge, he adds, is that “not all projects … are right for private investment,” and some communities that need investment don’t have money at hand to pay for it from taxes or user fees like tolls.

On top of that, some projects – such as a proposed new rail tunnel from New Jersey into New York City – span local, state, and federal purviews. The project matters to Manhattan-bound commuters, but also to flows of freight and people along the whole Northeast corridor. All this leaves plenty of room for debate over the proper federal role and purpose in infrastructure.

“That’s the real point of contention,” Mr. Puentes says.

A plan with scant details

Trump offered scant details during his televised State of the Union address in Congress Tuesday night, but he used the speech in part to paint himself as open to compromise with a Congress where Senate legislation will hinge on bipartisanship. While emphasizing themes that would resonate with his conservative base, he also sought to draw Americans together on goals involving national security and economic improvement.

“Tonight, I'm calling on Congress to produce a bill that generates at least $1.5 trillion for the new infrastructure investment that our country so desperately needs,” Trump said. “Every federal dollar should be leveraged by partnering with state and local governments and, where appropriate, tapping into private sector investment to permanently fix the infrastructure deficit.”

His other specific call was for speedier permits, to bring the approval process “down to no more than two years, and perhaps even one.”

Judging by comments from his administration, and a leaked draft document recently published by Axios, Trump’s goal is to hit that $1.5 trillion target (over 10 years), while spending just $200 billion or so in federal money, using it to reach the larger total by incentivizing the local and private investment.

Critics have voiced a host of concerns, including that speedier permitting as outlined by Trump would come at the cost of undercutting environmental safeguards, but also that the budget math isn’t adding up.

“Democrats agree with the president: America’s physical infrastructure is the backbone of our economy, and we have fallen behind,” Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer of New York said in a commentary published ahead of the address.

Presidents Eisenhower and Reagan were Republicans who understood “that direct investment of federal resources was the best way to maintain and build our nation’s infrastructure,” Senator Schumer said. “Only a plan with direct investments can properly address the scale of the challenge we face.”

His concern is shared by many outside experts, who say it’s quite possible that Trump’s coming budget plan will include no net increase for infrastructure (perhaps adding some new funds while cutting back on other existing programs).

A plan that’s tight on federal money risks leaving some areas of the country – notably poorer cities or ones facing population loss – behind.

Already, the trend in federal funding has been downward. Federal spending on infrastructure, while not down drastically, is lower as a share of the nation’s gross domestic product than it was in the 1960s and ‘70s, with a modest rise under President Obama’s post-recession stimulus package balanced by a decline later in his term.

So the question may be: Is the federal retreat from infrastructure funding palatable, even prudent – or a problem?

At present, the parties seem far apart on that question. Democrats also appear little-inclined toward any compromise that could give Trump and Republicans a legislative victory to tout heading into the midterm elections this fall.

“Our nation’s roads, bridges and tunnels would become tools for wealthy investors to profit off the middle class, rather than the job-creating public assets they ought to be,” Schumer warned in his commentary, voicing a common Democratic concern about private sector partnerships.

Nor is Trump's legislative path smoothed by the fact that a federal fund for highway projects is in deep need of a refill. His new tax cuts, meanwhile, may make it harder for state and metro areas to dig up their own financing for projects.

Potential for common ground

Still, if the partisan rift is real and considerable, so is the potential for common ground over time – since already the nation’s overall pattern includes big roles for federal, state, and private investment.

“There is a growing consensus that the United States should boost investment in transportation infrastructure, but ... the United States is moving into an era where more of the agenda-setting and funding responsibilities are falling to local governments,” states a new report by Adie Tomer and Joseph Kane of the center-left Brookings Institution.

A key reason? Not Trump, but the way “local governments are also especially attuned to local needs.”

That can protect federal taxpayers: If localities have to raise the biggest funds, “bridges to nowhere” become less likely to be built. But the new report echoes the point made by Puentes (who’s also affiliated with Brookings): A city like Milwaukee doesn’t have the same money-raising potential as Denver or Seattle.

Trump’s plan appears to nod to that issue in one way: It sets aside funds for rural areas, which are among the places where it’s hard to lure in private investors with promises like long-term toll revenues.

Nationally, groups representing business, private-sector labor unions, and governors have joined to promote infrastructure plans that include both robust federal funding and private-sector partnerships, saying that the US needs “policies to deliver modern infrastructure more quickly and at less cost.”

Both Republican and Democratic states have already been relying on both public and private-sector projects – and tolls are just one way to pay for them. States also deploy gas taxes to fund infrastructure, and the next-generation approach may be mileage-based user fees, already being tested in blue states like California and Oregon, among other places.

Along the Kentucky and Ohio border, Democratic and Republican governors teamed up in 2015 to call for investing big local dollars – and for users to pay tolls – to replace a bridge from Cincinnati to Covington, Ky. The project is still pending, but the idea hasn’t gone away, because, well, people on both sides of the Ohio River need a bridge.

Share this article

Link copied.

Challenge to ‘open’ France: a blurring of migrants’ motives

When it comes to migrants and refugees, the old patterns and assumptions don't hold anymore. Recognizing that is central to addressing record movements around the globe.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

French President Emmanuel Macron is under fire at home for trying to empower his government to more speedily distinguish between economic migrants, whom they want to deport, and those legally in need of refuge. Critics say it is a sharp contrast with the strong human rights focus he has long espoused. But the greater challenge for Mr. Macron may be that the line he wishes to draw is one that is becoming blurry. Catherine de Wenden, a political scientist in Paris who specializes in migration, says that the sort of crackdown on economic migration that Macron is proposing is increasingly meaningless. “We have to differentiate because [economic migrants and refugees] have different legal statuses, but the profiles are very close now,” she says. “In some countries there is a mix of political crises and economic crises.” Push factors, such as abject poverty and drought, often coincide with war and persecution. “It is much more of a continuum than it was before,” says Elizabeth Collett, director of the Migration Policy Institute Europe in Brussels.

Challenge to ‘open’ France: a blurring of migrants’ motives

French President Emmanuel Macron came into office promising to make France the “new center of the humanist project.” It’s an oft-repeated theme seen as a repudiation of the far right at home and of leaders in Europe and across the Atlantic who have scored points by rallying for closed borders and railing against immigration.

“France has always been the country of enlightenment, not darkness,” he told anti-immigrant rival Marine Le Pen in their final campaign debate. Then in his acceptance speech outside the Louvre museum, he spoke of a global expectation now for France to “defend the spirit of the Enlightenment that is threatened in so many places.”

Except now Mr. Macron himself is under fire for betraying those ideals – as his government plans to write a new law to more speedily distinguish between economic migrants, whom they want to deport, and those legally in need of refuge.

His supporters say he is just operating out of political realism. Foes say his lofty rhetoric of France as the birthplace of droits de l’homme (human rights) doesn’t match the crackdown on the ground. But underlying it all is a larger global tension, as the lines between economic migration and crisis-driven migration blur – and the push factors, like abject poverty and drought, coincide with war and persecution. Many question whether the United Nations’ definition of a refugee should be expanded to reflect the reality of crisis today.

“It is a broader discussion being had at the international level,” says Elizabeth Collett, director of the Migration Policy Institute Europe in Brussels, as it is more “difficult in humanitarian terms to distinguish between the acuteness of need some people are experiencing… It is much more of a continuum than it was before.”

Humanism vs. realism

In France, Macron’s government has said that the most humanitarian path forward is to make the asylum system more efficient. But that means a harder line for undocumented immigrants. He echoes the oft-repeated statement of Michel Rocard, a Socialist prime minister from 1988 to 1991, who crossed an ideological divide when he said, “France cannot welcome all the misery in the world.”

Among the most controversial moves by the government was a circular released in December allowing authorities to conduct identity checks in emergency shelters. Leading Catholic and Protestant organizations penned an open letter condemning the move. “At its heart it’s a hostile measure, a mistrust of people,” says Bruno Magniny, director of a welcome center for charity Secours Catholique, one of the letter’s signatories.

Even some of Macron’s former allies have spoken out. In another open letter in Le Monde this month, a former top advisor, Jean Pisani-Ferry, along with unions and intellectuals, criticized Macron’s policy as one that “contradicts the humanism you are advocating.”

A magazine cover this month sums up the dissent with a mug shot of Macron behind barbed wire, provocatively declaring: “Welcome to the country of human rights.”

Alain Minc, a former mentor of Macron, says his immigration policy fits into Macron’s ethos as a president neither on the right nor left. “I think the question about immigration is theoretically very simple,” he says. “We should be as open as necessary vis-à-vis the political refugees and war refugees but not vis-à-vis migrants coming from what … are called ‘safe countries.’ ”

In fact what Macron is proposing is nowhere near as radical as policies floated by President Trump in the United States. It is in line with mainstream policy in Europe, which aims to balance welcome for those truly in need of it and a functional border policy, including national security. Germany’s “welcome” of refugees at the peak of flows in 2015 was accompanied by a similar bifurcation of the system to better distinguish between two sets of migrants.

A migration continuum?

But Catherine de Wenden, a political scientist in Paris who specializes in migration, says that a crackdown on economic migration is increasingly meaningless. “We have to differentiate because they have different legal statuses, but the profiles are very close now,” she says. “In some countries there is a mix of political crises and economic crises.”

Although Macron’s government has said it has increased deportations of undocumented migrants, Ms. de Wenden says it remains a difficult task once they are here, even with a harsher crackdown. She estimates that only 5 percent are eventually sent back. Ms. Collett adds that in Europe, many governments who don’t grant asylum still implicitly recognize that it is difficult to return certain migrants – like 19-year-olds from Afghanistan, for example – back home, which leaves them in a legal limbo.

At the orientation center run by Secours Catholique in the northeast corner of Paris, migrants sip coffee under red and white snowflake decorations. Children play with donated toys in a corner. Ibrahim, who came from Ivory Coast in 2016 and is awaiting his asylum claim to be processed, says migrants still believe in France as a country of droits de l’homme, but the situation on the ground is sobering. “We are escaping a difficult situation to come to live out another difficult situation,” he says.

Mr. Magniny, the director of this center, says he believes Macron is following public opinion in France instead of setting an example. Magniny calls Macron’s tougher policies a “historic error” in a changing world where migration is a reality.

“The fear of the migrant is real, it exists. But it is an irrational fear, a fear of the future,” he says. By creating a climate of crackdown, Magniny says, Macron is only adding to a climate of fear of others. “And you don’t prepare for the future cultivating fear in people,” he says.

Reaching for equity

For Afghan women, Western help can complicate a climb

It's easy to make assumptions that exacerbate already significant divides between those of different cultures. But there can be common ground from which to drive progress, if you're willing to look, as Scott Peterson explores in the fourth story of our series.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The United States has put a lot of effort into beefing up women’s rights in Afghanistan over the past 17 years. And a lot of money, too: $1.5 billion since American troops overthrew the Taliban government. But the results don’t always reflect that input. Certainly there are plenty of success stories: “Women learned to fight for their rights,” says one young female lawyer, and there are lots more professional women like her in Kabul today who would agree. At the same time, far fewer women die in childbirth now than 15 years ago. Some, though, say the reforms could have gone deeper if they had been better thought out for a conservative Muslim society. Western non-governmental groups might have drawn more attention to the Quran’s support for gender equality, perhaps, and spent less time stressing gender-neutral vocabulary. But where the Taliban banned girls from school and women from the workplace, new attitudes are taking root. After a recent meeting, who asked women’s activist Maryam Durani to advise his daughters how to continue their studies? A senior Muslim cleric.

For Afghan women, Western help can complicate a climb

What do you call a female journalist in Afghanistan?

A prostitute.

That’s no joke. And none know it better than the reporters and producers working at “Zan TV,” an Afghan channel devoted to empowering women.

The all-female TV station operates from an anonymous office down a narrow, pot-holed lane in Kabul, hard by a building belonging to the Interior Ministry. Asked where the “Women’s TV” office is, one of the ministry’s bearded, uniformed guards smirks.

“The sex center, it’s over there,” he replies, pointing to an unmarked door along the lane. “Go on, you will have a great time with those girls.”

His response encapsulates the continuing challenge for Afghan women to learn, to work, and to be respected by Afghan men. But “Zan TV,” which broadcasts news and features around the clock to a female audience, is on a mission to change that kind of sexist attitude.

“Our job is to work on people’s minds,” says Shogofu Sediqi, the jeans-clad executive producer who wears a royal blue headscarf. “I introduce the real picture of what women can do.”

Beefing up women’s role in Afghan society has been a cornerstone of Western policy ever since US forces helped topple the hard-line Islamist Taliban government in 2001. The Taliban had famously refused to allow girls to go to school or women to work outside the home, rolling back rights that women had once enjoyed. (Afghan women won the right to vote in 1919, a year before their counterparts in America, for example.)

By one count, the United States has poured $1.5 billion into efforts to educate Afghan girls and women, to impose quotas for women in government and the security forces, and to bring them into the workplace, among other projects. The goal has been to transform a deeply conservative society known more for child brides, misogyny, and honor killings than for feminism.

There is pride in accomplishment among the growing ranks of women in government, the security forces, and professional life. But both in the towns and the countryside, women working for change are still often harassed, pressured, threatened, and killed for their pains.

Legal advice that cost a life

Zarghona Alokozay, an energetic young lawyer who sports purple nail polish, is one such woman. Since a man threatened before a judge to kill her three years ago, she takes care to vary her routine each day on her way to and from court. Recently she asked the government to provide guards to protect the “Justice for All Organization” (JFAO) legal offices in Kabul, where she and her colleagues are overwhelmed by cases of forced marriage, domestic violence, and other infringements on women’s rights.

But there was nobody to protect Shuibah Naimi, a 26-year-old JFAO lawyer in rural Laghman province, east of Kabul, when angry men came for her in early January. They shot her dead for helping a relative of theirs – a widow who wanted to remarry, an act they deemed shameful.

Such sacrifices are a high price to pay. “The front lines are always bloody places, including the front lines of culture wars,” says a Western official who has lived for years in Afghanistan and who asked not to be identified. “This generation of Afghan women that is trying to promote social change has had it unspeakably bad.”

In the bigger picture, though, argues Ms. Alokozay, “we got a great result” from Western spending on women’s issues in Afghanistan. “Women learned how to fight for their rights,” she says. “When one woman raised her voice, then others would follow and be inspired. In the past, it would be hidden.”

Certainly, a wide range of projects have successfully promoted the women’s agenda; the number of highly qualified women is rising, and the number of women who die in childbirth has fallen by 75 percent since 2002.

“But that is not enough,” says Deputy Minister for Women’s Affairs Spozhmai Wardak.

Sitting behind a wide desk, a male secretary in her outer office, she complains that the changes have not gone as far or as deep as they should have done and that the overall result of Western donors’ spending has “not been very positive.”

That, she explains, is because many non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) often use Western teaching materials that don’t fit the Afghan cultural context, lending the gender equality message a foreign tone. They focus on gender-neutral terms, for example, but they don’t point to verses in the Quran such as “be you male or female – you are equal to one another,” or other Islamic religious teaching about gender equality.

Western advocates for women’s rights also tend to work more in the cities, addressing open-minded urban women already converted to the cause of equality, Ms. Wardak points out. In more conservative rural areas, where the message has not yet spread, it is sensitive, if not downright dangerous to speak about women’s status.

Bollywood vs. Taliban

For Wardak, feminism in Afghanistan is a nitty-gritty business that should tackle real life situations, such as making sure that police posts have separate changing rooms and toilets for women so as to make their lives on the force easier and sexual harassment harder.

“A work environment should be available to women (that gives them) different benefits and special facilities,” Wardak argues.

In 2016, the US spent $93.5 million on measures – including more such facilities – to boost female recruitment into the security services. But it’s an uphill battle.

Nearly a decade ago, NATO and Afghanistan declared that by 2020 they wanted 10 percent of positions in the security forces to be filled by women. That figure currently stands at 1.4 percent.

It doesn’t help that the security forces are notorious for sexual harassment and blackmail. Afghanistan had its own Harvey Weinstein moment last November when a video surfaced of an Afghan Air Force colonel coercing a woman into having sex as the price of her promotion.

In a society traditionally as male-dominated as Afghanistan's, it is not easy to instill the idea that such behavior is wrong. The Ministry for Women’s Affairs is trying to reshape social attitudes, though, with a series of TV advertising spots that use music and simple scripts to highlight women’s rights issues, the value of educating girls, and the message that beating women and forcing them into marriage against their will are wrong.

“Ten years ago there was no TV,” says Shakila Nazari, the Women’s Affairs Ministry communications director. “Compared to 10 years ago, there is huge progress in our work, all over Afghanistan.”

And it’s not just television. 3G access across much of Afghanistan now allows cell phone users to stream video.

“Things are changing, and I think people are changing it themselves,” says the Western official. “People can choose whether they want to watch Taliban propaganda or Bollywood. And guess what? They tend to watch Bollywood."

But the Taliban have not gone away. Insurgents control or contest well over one third of the country, and “you can’t ignore the way that the West bringing its values to Afghanistan has incited conflict,” says the Western official.

Police Capt. Zahra Ghaznawi, sitting in her spotless office decorated with three big bouquets of plastic flowers and five certificates of achievement, is in no doubt as to which side of that conflict she is on. Wearing make-up and a black headscarf tucked into her camouflage uniform, the mother-of-three, 16-year veteran of the force is a no-nonsense officer who speaks with pride about her job.

It can be dangerous work. Last Saturday, Captain Ghaznawi lost five female colleagues to a Taliban bomb hidden in an ambulance that exploded outside the Interior Ministry complex where she works, killing more than 100 people.

“I am very happy to wear this uniform because it has a positive effect on other women,” says Ghaznawi. At a recent Kabul University ceremony honoring successful women, she recalls, “many students took their picture with me, and said they wanted to be policewomen. I was really proud of myself.”

“As long as I am alive, I will work for my country,” she adds.

An unexpected question

Also at the Kabul University ceremony, collecting a media award, was Maryam Durani, a well-known women’s activist and radio entrepreneur from Kandahar, the deeply conservative former bastion of the Taliban.

“My first target in Kandahar was that everyone should accept me as a person, with equal rights,” she says.

Ms. Durani’s “Women’s Radio” station claims an audience of 800,000 for its programs highlighting violence against women, women’s education, and women’s rights. Its impact is such that the Taliban once sent a letter – complete with an official stamp – warning that if the radio did not stop broadcasting within 48 hours, Durani would be killed.

It didn’t, and she wasn’t. But Durani still has scars on her hands and her head, reminders of a suicide attack on the Kandahar provincial council in 2009, when she was an elected member.

She has happier memories, too, recalling with special pleasure a women’s event in Kandahar last year – held under the title “Afghanistan Needs You” – that she helped to present.

When it was over, Durani noticed a senior Muslim cleric, a member of the local religious establishment, approaching her. She braced for the critical onslaught she expected from him.

But the preacher had a very different purpose. Could his three daughters get in touch with Durani, he wondered? They needed advice on how to continue their studies.

“For me, that was so important,” says Durani. “It gave me more energy than any prize.”

Why wind power wavers in a state that’s been a leader

How do you make room for a new industry in a state's corporate incentives? In cash-strapped Oklahoma, some are saying what's needed is to move away from a sense of limitation that drives zero-sum thinking.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

How does an oil and gas state learn to integrate a promising new industry? Oklahoma has just become the No. 2 producer of wind energy in the United States, bringing an economic boost to communities that host the turbines. But it has also cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars in tax incentives – millions it can’t afford amid a deep budget crisis. Now a new project, Wind Catcher, which is slated to be one of the largest wind farms in America, is facing stiff resistance and could potentially be shut down altogether. Some see the conflict as stemming from a zero-sum view of Oklahoma’s economic potential. “We’ve spent too much time as a state [debating] who gets which slice of the pie,” says Brent Kisling, executive director of the Enid Regional Development Alliance and a supporter of wind power. “We ought to spend more time figuring out how to increase the size of the pie.”

Why wind power wavers in a state that’s been a leader

First the wind came sweeping down the plain, then the dollars, and now the controversy.

With ever more spiky wind turbines cropping up across its open lands, Oklahoma has just become the No. 2 state in the country for wind energy production, the American Wind Energy Association announced Tuesday. That has been a boon for local communities, but it has also come at a price for the state, which pays tens of millions of dollars a year in subsidies for wind companies. As the industry grows, so does the price tag for wind incentives.

Now a new project – Wind Catcher, which is slated to be one of the largest wind farms in America – is facing stiff resistance and could be scrapped altogether.

The Wind Catcher case comes amid a pushback on wind incentives, galvanized by a state budget crisis and influential oil and gas interests. In the past year, Oklahoma has ended two key incentives that even wind proponents admitted were in some ways “too generous.”

“I’m hopeful that the current balance that we’ve struck between local taxation and making sure that we’re not penalizing a new technology – I’m hopeful that that balance stays in place,” says state Sen. AJ Griffin (R) of Guthrie, who says she encourages investment in wind “without giving away the farm.”

But some are pushing not only to remove all subsidies, but to levy a new tax on wind.

One of America’s largest wind farms

Under the whirring of turbines in Oklahoma’s Garfield County, Craig Schlichting hauls rock, agricultural lime, and grain for a living.

He’s not particularly keen on wind, but with the agricultural economy flagging, he sees the industry’s positive effect on his community of Garber, Okla. There’s a new blacktop road being laid down, and a smart new school building a mile away. Then there's the wind companies’ payments to those with turbines on their land.

“It’s scuttlebutt, but the guys who have them say [the wind companies] pay $10,000 per year,” says Mr. Schlichting, standing in well-worn striped overalls. “In a poor state, it’s good money.”

The money coming into the county through such landowner payments is equivalent of the paying 194 employees at the county average wage – which would put it among the top-10 companies in the area, says Brent Kisling, executive director of the Enid Regional Development Alliance in Garfield County.

Now Enid stands to benefit from the $4.5 billion Wind Catcher project, which includes plans to build a 350-mile transmission line that would pass through the area, bringing supply-chain jobs, says Mr. Kisling.

Public Service Company of Oklahoma (PSO), which is investing $1.3 billion in the project, says Wind Catcher will save Oklahoma electric customers an estimated $2 billion over 25 years. That would be a relief for many in a state where summer electric bills often run $400 or more a month.

But there’s a problem.

$2 billion in savings? AG doesn’t think so.

PSO skipped a required competitive bidding process for building the transmission line. That was intentional: It wanted to finish the project before a federal tax credit expires at the end of 2020, says spokesman Stan Whiteford. Now it needs an exemption from the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC), which regulates public utilities.

PSO is asking the state to approve a rate hike to help finance its investment, and says that the added cost to consumers will be quickly canceled out by the savings of wind power. The OCC held hearings this month over whether to approve the exemption and the rate hike. A decision is expected in early spring.

One of the strongest opponents to the project is Attorney General Mike Hunter, whose job is to protect Oklahoma consumers.

However, Mr. Hunter disputes PSO’s savings estimate. He has experience with public utility cases, having previously worked for OCC, and says the Wind Catcher project is likely to cost consumers around $320 million.

He also underscores that PSO did not follow state rules, plain and simple, and must be opposed on that basis.

“My responsibility is to the ratepayers of the state of Oklahoma and that responsibility is a statutory responsibility, it’s consistent with my oath of office, and the case that we’re putting on is based on careful investigation, thoughtful review of evidence, and the law,” Hunter tells the Monitor. “And that is my sole motivation in this matter.”

What makes a level playing field?

Pro-wind critics argue that the opposition to Wind Catcher – and the wind industry in general – is being driven by influential oil and gas magnates like Harold Hamm, an ally of President Trump and former Oklahoma attorney general Scott Pruitt.

“Certainly everybody in Oklahoma knows there’s been a Harold Hamm vs. wind fight for several years,” says Jeff Clark, head of the Texas-based Wind Coalition. “He’s not intervening so Wind Catcher gets built more competitively. He’s intervening because he wants to kill Wind Catcher.”

Mr. Hamm’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment. But he has argued that wind subsidies are no longer necessary in light of a federal tax credit extension for wind, and says the subsidies primarily benefit out-of-state companies whose power often goes to out-of-state customers.

Jonathan Small, president of the Oklahoma Council for Public Affairs in Oklahoma City and an early member of The Windfall Coalition spearheaded by Hamm, says it’s more about free-market economics than favoritism.

“I think the vast majority of lawmakers and citizens would say it has more to do with lack of a level playing field than not liking wind,” says Mr. Small, a former budget analyst for the Oklahoma Office of State Finance. He says the budget crunch focused scrutiny on wind incentives, and cites a statistic that each turbine costs taxpayers more than a teacher's starting pay – a figure calculated by Wind Waste on an Apex wind installment in Oklahoma's Kingfisher County. (Teachers are in such short supply that some Oklahoma school districts have gone to four-day weeks.)

But proponents of wind argue that oil and gas subsidies cost the state significantly more than wind subsidies, despite wind's growth in recent years. A 2017 Oklahoma Policy Institute paper calculated that in fiscal year 2018 the state would forgo more than $500 million in revenue due to tax breaks for oil and gas.

“I think a lot of it is that [oil and gas entities] want to have their incentives, but they don’t think the wind should have the same incentives,” says Jan Kuehn of Kingfisher County, who has Apex wind turbines on her land as well as oil wells that still pay her royalties. “I think the wind people left the land and the roads in better shape than before they came – which is a great help because as most states, Oklahoma is strapped for money.”

In May 2016, Oklahoma’s secretary of finance announced that the state had needed to borrow $5 million from other funds that month to pay refunds due corporations, including $3.3 million in zero-emission credits to wind companies. The following year, the legislature ended that incentive for new wind farms, as well as a five-year property tax exemption.

Gov. Mary Fallin also proposed a production tax on wind to help close a nearly $1 billion budget gap for fiscal year 2018. Legislators are still pursuing that idea.

Kisling of the Enid Economic Development Alliance says what’s needed is a shift away from zero-sum thinking.

“We’ve spent too much time as a state [debating] who gets which slice of the pie,” he says. “We ought to spend more time figuring out how to increase the size of the pie.”

Satellite effect: what six decades of ‘overview’ has meant to humanity

It's age-old advice for dealing with a tough problem: "Step back" in order to see what matters most. Today, we're recognizing technological advances that have allowed us to do that with our own planet, yielding a similar breakthrough in perspective.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Sixty years ago today, the United States joined the Soviet Union in space with the launch of the Explorer 1 satellite. The space race that followed did not just expand our understanding of the cosmos and usher in new technologies, it also prompted a perceptual shift: After countless millenniums of looking up at the sky, we could finally look down from the sky at our own planet. This shift, known as the overview effect, has a way of erasing the distinctions between nations and cultures. “The astronauts see the Earth as a whole system, interconnected and complete,” says science writer Frank White, who named the effect. “And this leads to a new understanding of who we are, and where we are in the cosmos.”

Satellite effect: what six decades of ‘overview’ has meant to humanity

Rocket fire streaked across the dark evening sky over Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Jan. 31, 1958. The United States had just launched a satellite into orbit, piercing the barrier between our world and the rest of the universe.

The oblong Explorer 1 satellite wasn’t the first human-made object in space. The Soviet Union’s Sputnik claimed that title on Oct. 4, 1957. But the first successful launch of an American satellite made space exploration an international endeavor, paving the way for scientific discoveries of cosmic proportions.

In the 60 years since, our mechanical envoys and human voyagers have gone to places previously imagined only in science fiction. But it hasn’t all been about studying other worlds. Scientists have also turned a mirror back on our own planet. And between the discoveries about Earth made from the heavens, and the eye-in-the-sky perspective we’ve acquired, going to space has forever changed how we see our world and ourselves.

“We’ve always been looking up at the stars before the space program, and now we’re able to look down on Earth from space, which was transformative in itself,” says Jim Pass, executive editor of the Journal of Astrosociology and founder of the Astrosociology Research Institute.

From space, we’ve tracked wildfires, watched photosynthesis in action, monitored the ozone layer and ice sheets, charted weather patterns, mapped pollution, and discovered that there’s a jetstream within the Earth’s molten core. We’ve even mapped the prehistoric routes of the multi-ton statues on Easter Island. Furthermore, the space-based GPS has helped geologists hone the model of plate tectonics, painting a picture of a planetary crust that is constantly in motion, shifting and changing.

These scientific observations have given us a much more detailed view of the world we live in, but it’s not just tangible things that we’ve learned about Earth. The perspective we’ve gained by going to space has placed humanity in a cosmic context like never before.

“Because we saw weird stuff on other worlds, it made us think, okay, it’s our right to have weird stuff here on Earth,” says David Portree, space historian and community outreach specialist at Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration. For example, he says, we used to think that most craters on Earth were from volcanic eruptions, not the impact of space rocks. “Then when we started to look more carefully at impact craters on other worlds, we realized that they were all over the Earth, buried mostly, and highly eroded, but all over the place. And we started to understand that we get hit by these things, and they’ve affected the history of life, and all sorts of stuff.”

Seeing ourselves anew

Learning about other worlds has also helped us appreciate how unique Earth is. Before getting a closer look, we thought our neighbor planets would be quite similar to Earth. But Venus is hot, hot, hot, and Mars is turning out to be a pretty harsh place, too. And now, with probes exploring the Saturn and Jupiter systems, we’re finding that it may be the faraway outer solar system moons that bear the most similarities to Earth, despite being exotic in other ways. The icy crusts of Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa are thought to enclose oceans of liquid water, and Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, seems to have dynamic processes similar to those on Earth, too.

“By having space to compare our planet to, we see that our planet is really special. It’s dynamic, it’s covered with chemicals doing crazy things like reproducing themselves, it has water in three states instead of just one – in most places it’s just solid. It’s a unique and special place,” Mr. Portree says. “And so I think that over time that has gradually penetrated into people’s consciousness.”

While satellites and planetary probes have taught us a lot about our world and placed Earth in the context of the rest of the solar system, the moment that humans took to space was momentous in shifting our perspective of our world, says Jennifer Levasseur, curator in the space history department at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Most astronauts that have returned from space describe a shift in worldview that they have experienced by looking back at the Earth. “The astronauts see the Earth as a whole system, interconnected and complete. They realize that we live on a planet. It’s a natural spaceship that’s moving through the universe. And this leads to a new understanding of who we are, and where we are in the cosmos,” says Frank White, who has detailed this phenomenon in his book “The Overview Effect.” “While we know this intellectually – we know we live on a planet – the experience we have everyday is not that. It’s that we live on a stable platform with the heavens rotating above us, the sun rises and sets.”

But it isn’t just about orientation. Astronauts have also described a feeling of stewardship and protectiveness, as seeing the Earth as a small orb hanging in the dark void of space makes it seem more precious. Many have pointed to just how thin of a protective blanket our atmosphere appears from space. And others have noted how the effects of climate change and pollution can be spotted. Astronauts frequently use words like “fragile” and “oasis” to emphasize how they’ve seen the planet.

For some, war, borders and divisions fade away, and the astronauts say they see unity in humanity and the interconnectedness of nature. That’s not to say that the diversity and chaos you experience down on the surface of Earth isn’t there, Mr. White says. “The overview effect gives us an understanding of diversity within a context of unity. You have to be able to hold both ideas at once.”

Kinship with the cosmos

Returning to the surface of the Earth with this new awareness, some astronauts have gotten involved in environmental movements or peace-building activities. Others have made it their mission to share this perspective with those of us who don’t make it up into space.

This has largely been done through photography, starting with the famous “Earthrise” photo taken from lunar orbit during the Apollo 8 mission. That and other images taken during the Apollo missions particularly captured people’s attention, and the dramatic visual of our spectacular home against the vast black of space was even used in the environmental movement that was picking up steam at the time.

As images flood in from the International Space Station today, people reflect on their habits, too. Just like you can see glaciers breaking apart and other effects of climate change, people have also been struck by the sparkling of artificial lights across the globe. This has prompted an awareness of light pollution, Portree says. “That’s interesting because light pollution keeps you from seeing space, and then from space we can look back and see why we’re not seeing space. And people are looking at those images and saying, I want to see that bright dot smaller.”

Images of space have had a profound effect, too, Dr. Levasseur says. The Hubble Space Telescope images, for example, have shown us just how picturesque and diverse the rest of the universe can be, and these pictures have stimulated intrigue among the public in the scientific information that they hold.

Not everyone may be profoundly changed on a day-to-day basis by the perspective we’ve gained by going to space, Portree says. But “I think that the potential exists in a lot of people to feel a kinship with the cosmos because we know more about it.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

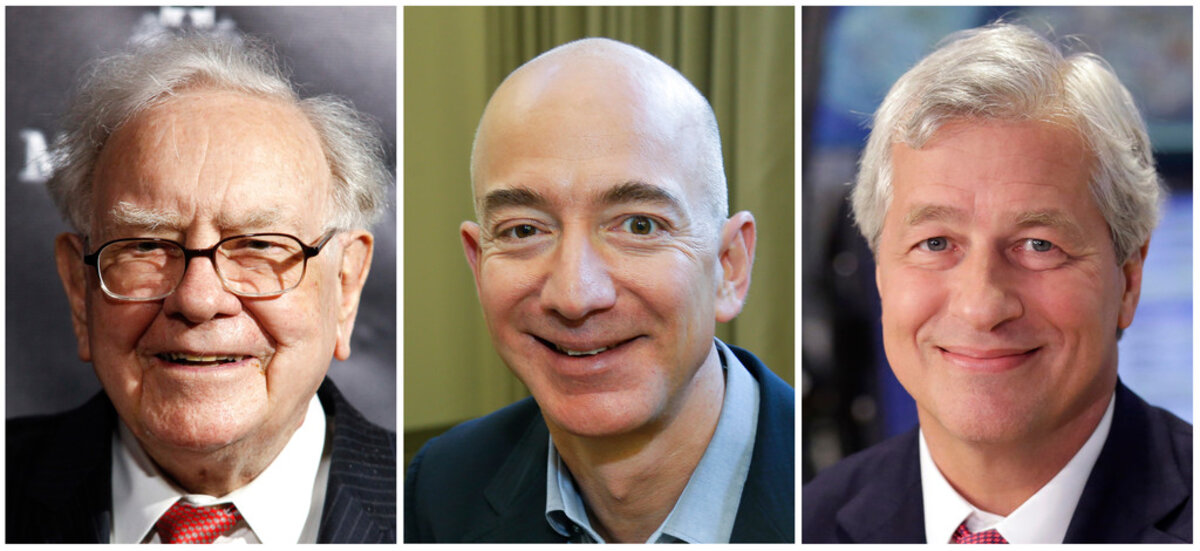

Amazon and friends try to heal the healers

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

The health-care industry has long been considered “too big to disrupt.” Yet Amazon, along with investor giant Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase bank, aims to challenge that thinking. “Our group does not come to this problem [of ballooning costs] with answers,” said Berkshire chairman Warren Buffett. “But we also do not accept it as inevitable.” Humility and hope are good starting points. Better technology and clever ideas may bring new efficiencies. But one big issue lies in defining the quality of care. There, Amazon and its partners could take a cue from Florence Nightingale. The 19th-century nursing pioneer helped launch a tradition of innovation in medicine. Yet her greatest contribution may be in promoting the idea that health is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. She focused more on the total well-being of a patient than on the sickness. “How very little can be done,” she stated, “under the spirit of fear.” Attending to people’s biological needs should include attention to their mental, moral, social, and spiritual aspects with evidence-based practices. Healing is more than fixing the body. It also entails a wider view about quality of health.

Amazon and friends try to heal the healers

One of Amazon’s “leadership principles” for its employees calls on them to keep “looking around corners for ways to serve customers.” Another one is to “not compromise for the sake of cohesion.”

Such creative approaches may help explain why the Seattle-based e-commerce giant has decided to join forces with two other big companies and disrupt an industry that commands a fifth of the American economy: health care.

The health-care industry has long been considered “too big to disrupt” with the kind of innovation that, say, has transformed retail (Amazon), urban travel (Uber) or commercial flying (Southwest). The federal government, too, finds it difficult to rein in costs with efficiencies or promote innovative management. Yet Amazon, along with investor giant Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase bank, announced Jan. 30 that they plan to provide “simplified, high-quality and transparent healthcare at a reasonable cost.”

These three corporate titans will first focus on their own employees, which number close to 1 million. But their ultimate goal is to show other companies how to bring higher productivity in health-care plans for their employees.

“Our group does not come to this problem [of ballooning costs] with answers,” said Berkshire chairman Warren Buffett. “But we also do not accept it as inevitable.”

Humility and hope are good starting points. Better technology and clever ideas may bring efficiencies to providers, such as hospitals and insurers. And employees can be better nudged to use the least-expensive health care or be given incentives to be healthy. But one big issue lies in defining the quality of care. Americans expect the best in treatments. And they have grown accustomed to letting others, for the most part, pay for it.

Rather than focus primarily on productivity, Amazon and its partners may want to take a cue about quality of care from Florence Nightingale, one of the biggest disrupters in the health-care industry. The 19th-century nursing pioneer raised the standards of health care by introducing many techniques. She helped launch a long tradition of innovation in medicine. Yet she also warned against those who would treat patients with the same efficiency that they would “take care of furniture, porcelain or even an animal.”

Nightingale’s greatest contribution may be in promoting the idea that health is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. She focused more on the total well-being of a patient than the sickness. Attending to people’s biological needs should include attention to their mental, moral, social, and spiritual aspects with evidence-based practices. Over the past 150 years, that idea has steadily taken root, all the way up to the World Health Organization.

The best health-care providers, she advised, help patients rid themselves of apprehension and uncertainty. “How very little can be done under the spirit of fear,” she stated.

These nonmedical aspects of health care are as worthy of attention from today’s innovators as other aspects of the industry. Healing is more than fixing the body. It also entails a wider view about quality of health.

The task of reducing health-care costs will be easier with a renewed focus on the overall well-being of patients. That’s the greatest lesson from one of the industry’s greatest disrupters.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding home in letting our light shine

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By John Biggs

Today’s column explores how one man’s desire to express Godlike qualities such as love, peace, and joy brought him a deeper, truer sense of home that can never be lost.

Finding home in letting our light shine

Many today are yearning for a fuller sense of home. The idea of home is more than a place, a feeling of being safe, or of knowing we’re cared for; it’s also a feeling of having a purpose, and a sense of belonging. How can we better feel this sense of home, and even welcome others into that precious home circle?

A while ago, I was visiting family in South Africa. I have always loved that country, and of course I love my family, so it wasn’t hard to find a comfortable groove once I arrived. But within a few days, I found myself rebelling against simply having a self-focused vacation; I really wanted to feel like I had a purpose there – like I really belonged.

I was soon able to find an opportunity to volunteer, teaching disabled Zulu and Xhosa children how to ride on horseback. Seeing the smiles on these precious children’s faces, realizing that love truly is universal, rejoicing in their victories, and supporting them in their struggles, I discovered a true sense of purpose.

Interestingly, directly in tandem with my dawning sense of selfless service, I was also finding a deeper, truer sense of home – a real sense of belonging. The landscape I looked on was the same, my family was the same, but I was mentally looking outward instead of inward, and in that way, I found home. No, I didn’t move to that beautiful country; this was a deep, abiding, spiritual sense of home that came to me, which was independent of place. Yet it has proved to be a rock and a shelter ever since.

I like to think of this experience as learning to “let my light shine.” Christ Jesus put it this way: “Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works and glorify your Father in heaven” (Matthew 5:16, New King James Version).

In a way, it’s natural that I found my sense of home as I let my light shine, because we see most clearly when there is light! But the light Jesus was talking about wasn’t a physical or personal light, but rather a recognition of what we truly are – what God, our Father and Mother, made us as. That spiritual sense of things, that spiritual light, reveals the substance of Spirit, God – including a deeper, more permanent sense of home. As this verse from a poem titled “Home” explains:

Home is the Father’s sweet “Well done,”

God’s daily, hourly gift of grace.

We go to meet our neighbor’s need,

And find our home in every place.

(Rosemary Cobham, alt., “Christian Science Hymnal: Hymns 430-603,” No. 497)

Jesus’ command to let our light shine includes this result: to “glorify your Father in heaven.” We don’t let our light shine so that we can show off how good we are. We shine, or express God’s joy and love, so we can show how good God is!

Christian healer, teacher, and founder of this newspaper Mary Baker Eddy elaborated on this idea when she wrote, “Man is not God, but like a ray of light which comes from the sun, man, the outcome of God, reflects God” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 250). As the creation, or outcome, of God, it’s natural that we would each be able to show what God is like, to live our true identity as the spiritual reflection of His peace and goodness. And it’s there, in God’s infinite love, that we find our true home, which can never be lost because we can never be separated from God.

All of us have the ability to let our light shine and therefore see more of what we are, and what our purpose is. Because we are the spiritual outcome of God, to know ourselves – including our sense of home – is a fruit of knowing God. It’s not a frantic search through real estate listings, or couch-surfer ads that will yield this sense of home. It’s letting God’s love minister to us, being alert for the ways His love is being expressed, and being willing to keep embracing others in that growing sense of home.

A message of love

A lunar rarity

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. Tomorrow, we'll visit some bookstores around the country that are reporting an increase in titles which take on the political zeitgeist through a variety of voices. And as they long have done, they're providing a place for people to come together, connect with their children, and adjust the dial on daily life for a bit.