- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Nikki Haley, known for a lead-from-in-front style, exiting UN post

- Business case for climate action grows as an agency intensifies warnings

- After historic Van Dyke verdict in police shooting, Chicagoans look to the future

- Venezuela crisis: In Latin America, a surge in tough rhetoric on borders

- Aspects of Africa that the first lady could have seen

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Banned in Florida

A hurricane is spinning up in the Gulf of Mexico. Preparations at Florida’s Santa Rosa County Sheriff’s Office include the following:

• Time off canceled for all personnel. Check.

• Backup generator fueled up. Check.

• Trespass warning issued to Jim Cantore. Check.

That’s right, The Weather Channel meteorologist is so synonymous with hurricanes that this sheriff’s office is covering all its bases.

Mr. Cantore has made a career of leaning into buffeting winds, whipped by rain, and shouting about the conditions. He didn’t invent the storm stand-up, but arguably he’s taken it to new levels.

The Cantore trespass warning is a joke. But the storm isn’t.

Hurricane Michael is intensifying in the Gulf and is forecast to hit Florida’s Panhandle as a Category 3 storm Wednesday evening. Florida Gov. Rick Scott declared a state of emergency for 35 Florida counties and encouraged evacuations. Due to the pending storm, Tuesday’s voter registration deadline was extended by a day.

No word yet on where Cantore is headed.

But whatever storms may threaten, there’s wisdom in preparing like the Santa Rosa County Sheriff's Office – with a sense of humor.

Now to our five selected stories, including the quest for justice in Chicago, the corporate ethics of responding to climate change, and how our correspondent challenges stereotypes about Africa.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Nikki Haley, known for a lead-from-in-front style, exiting UN post

Nikki Haley, US ambassador to the United Nations, represented both a politically conservative – and provocative – approach to geopolitics, which wasn’t always in sync with the president. Here’s our look at how she influenced US global policy.

UN Ambassador Nikki Haley’s resignation Tuesday sent shock waves – certainly through New York diplomatic circles that had come to rely on her as a kind of decipherer of bewildering foreign-policy turmoil in Washington. Very little was immediately clear about the whys of her resignation, which President Trump accepted and will take effect at the end of the year. One of the few members of Mr. Trump’s original national security team still standing, Ms. Haley had at times stepped out in front of the administration with tougher and more provocative positions – on issues from Iran and Russia to human rights – than even the president seemed to support. For some in the White House, the ambassador’s lead-from-in-front initiatives were known to rankle as showboating that stole the spotlight from the president – a clear Trump White House no-no. Yet while Haley may have been out in front of Trump on some issues, on others she was in complete sync. Perhaps the clearest example of that was in her “America First” perspective of the United Nations as a bloated bureaucracy happy to feast on American financial support while disdaining its values and leadership in world affairs.

Nikki Haley, known for a lead-from-in-front style, exiting UN post

When an anonymous “senior official” in the Trump administration penned an op-ed piece in The New York Times last month chronicling chaos and deep policy divisions in the White House, Nikki Haley offered her own take on the infighting.

President Trump’s outspoken ambassador to the United Nations – who was suspected in some circles of being the disgruntled “anonymous” – skewered any speculation that she could be the author of any such back-stabbing.

“I don’t agree with the president on everything,” she wrote in a signed op-ed in The Washington Post. But “when there is disagreement, there is a right way and a wrong way to address it,” she wrote. “I pick up the phone and call him or meet with him in person.”

Ms. Haley’s resignation Tuesday as UN ambassador sent shock waves through an already reeling Washington – and certainly through New York diplomatic circles that had come to rely on Haley as a kind of decipherer of bewildering foreign-policy turmoil in Washington. By some accounts, even the White House was shocked when Haley first broached the idea of resigning in a meeting with the president last week.

Very little was immediately clear about the whys of Haley’s resignation, which Mr. Trump accepted and will take effect at the end of the year. The high-profile politician’s explanation Tuesday that she needed a break after two years on the global stage (which followed eight years as governor of South Carolina) convinced few in Washington.

What was more apparent was how Haley, one of the few members of Trump’s original national security team still standing, had over her tenure sometimes stepped out in front of the administration with tougher and more provocative positions – on issues from Iran and Russia to human rights – than even the president seemed to support.

For some in the White House, the ambassador’s lead-from-in-front initiatives were known to rankle as showboating that sometimes had to be walked back, but which always stole the spotlight from the president – a clear Trump White House no-no.

Two recent examples: one involving Iran, the other Venezuela.

Haley engineered (and publicly announced) a Security Council session during UN General Assembly week last month that was to focus on Iran and its “malign activities” – and would be chaired by Trump.

By all accounts the president was fired up to lead such a diplomatic assault on Iran. But other national security policymakers worried the format would leave the US looking isolated, rather than Iran – and in the end Haley’s Security Council meeting morphed into a bland session on nonproliferation.

And then on Venezuela, Haley floored a boisterous crowd protesting the government of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro outside the UN last month when she hopped out of her limo, bullhorn in hand, and shouted to the protesters’ roaring approval that she and Trump have their backs.

“I can tell you that I talked with President Trump and he is fired up about this,” she told her bedazzled audience. “He is angry at Maduro. His comments were we are not just going to let the Maduro regime backed by Cuba hurt the Venezuelan people anymore.”

The problem is that, aside from some tough words and some additional sanctions on Venezuelan officials, Trump is not showing any signs of doing anything of consequence toward the Maduro government or to change Venezuela’s downward spiral.

'I don't get confused'

Even on Russia, Haley has at times staked out a hard-line position that went beyond where Trump, who has expressed admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin, was prepared to go. Last year she went on Sunday news programs to announce that the US would be slapping a new round of sanctions on Russian entities involved in Moscow’s intervention in Syria on behalf of President Bashar al-Assad.

Not so, responded the National Economic Council director, Larry Kudlow, adding that Haley must have been “confused” about administration intentions.

That did not sit well with Haley, who publicly fired back that “with all due respect, I don’t get confused.”

Haley’s departure was lamented by some, including some in Congress, who see it as both another sign of chaos in the administration’s foreign policy team and a loss for the promotion of America’s values internationally – including human rights.

“I want to thank Ambassador Haley for her willingness to express moral clarity to the world, and to President Trump, and promote American values and leadership on the global stage, even when she lacked the backing of the White House or State Department,” said Sen. Robert Menendez (D) of New Jersey in a statement Tuesday.

Also citing Haley’s staunch promotion of America’s values was Sen. Ben Sasse (R) of Nebraska, who praised her for standing up “with clarity and strength” to “dictators” who would use the UN as “a platform to give lip service to human rights.”

Mr. Menendez and Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio – whom Haley supported in the 2016 Republican presidential primaries – both have pushed the Trump administration on human rights, particularly concerning Cuba and Venezuela. And both have expressed support for Haley’s championing of human rights (as selective as that championing may have been) within an administration that from the outset has shown little interest in the issue.

In sync on 'America First'

Yet while Haley may have been out in front of Trump on some issues, on others she was in complete sync. Perhaps the clearest example of that was in her “America First” perspective of the UN as a bloated bureaucracy happy to feast on American financial support while disdaining its values and leadership in world affairs.

Haley seemed to relish her role in cutting US contributions to the world body and withdrawing from a number of its agencies. Announcing the US pullout from the UN Human Rights Council earlier this year, she blasted the body as a “cesspool of political bias.”

In accepting Haley’s resignation Tuesday, Trump said he had a number of potential replacements in mind – and he ventured that filling the slot will be easy because Haley had made the job “more glamorous.”

Names already floating around as possible replacements include Dina Powell, Trump’s former deputy national security adviser (who reportedly spent last weekend with Haley); the US ambassador to Germany, Richard Grenell, who was National Security Adviser John Bolton’s spokesman when he was UN ambassador; and – Ivanka Trump.

Whoever it is, Haley’s replacement seems likely to be someone who gets out in front of the president less. Among other things, Venezuela protesters may have seen their last bullhorn-toting US ambassador to the UN pledging enthusiastic presidential support.

Business case for climate action grows as an agency intensifies warnings

The arrival of a new climate change report calling for urgent action struck Monitor editors as the right moment to look at the financial and moral imperatives behind corporate efforts to tackle the problem.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The message delivered Monday by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was clear: Every sector of the world's economy is needed if we have any hope of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C above preindustrial levels. While previous calls to action have focused on government-imposed legislation, a growing number of corporations are taking pledges of their own to reduce their contributions to climate change. Of course, no one is pitching corporate action alone as the solution. And indeed the corporations are taking action partly under pressure from governments, consumers, and environmental groups. But their rising urgency also stems from what many see as a simple business calculation: A healthier planet means bigger market opportunities, and a less-hospitable planet the reverse. “We succeed when those around us succeed,” says Kevin Rabinovitch, global vice president of sustainability at Mars Inc., the candy company based in McLean, Va. “You can’t run a successful business in a failing economy or a failing environment.” This goes hand in hand, he says, with the moral argument that caring for the environment is “the right thing to do.”

Business case for climate action grows as an agency intensifies warnings

A new global report from scientists amounts to an urgent call for the world to act more quickly and forcefully to counter fast-rising threats from climate change.

The report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Monday said humanity’s window for action is quickly closing, if the goal of holding global warming to 1.5 degrees C above preindustrial averages is to be met. And the report emphasized the benefits of aiming for that target, rather than allowing temperatures to rise 2 degrees C or more due to the buildup of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere.

For coral reefs, for example, that half a degree could be the difference between a huge decline and a near-total loss of those ecosystems, the report estimated. Two degrees of warming would thrust an additional 489 million people into conditions of water scarcity, double the increase expected for a 1.5 degree threshold.

Of course, while this latest IPCC report frames the challenge in some fresh ways, such urgent calls to action have happened before. One of the challenges is that a dire forecast alone, even when coupled with careful scientific explanations, can sometimes spark feelings of fear, resentment, or helplessness rather than concerted action. But this time, even as the report prompted social-media reactions of “we’re doomed” or “we’re cooked,” other shifts may give a nudge toward hope and engagement.

Technological advances, such as breakthroughs in solar energy and electric-vehicle batteries, are making the reduction of fossil-fuel emissions look more feasible. And, from droughts and wildfires to storms and floods, the “lived experience” of many people in the past few years is making action look more necessary.

The scenario outlined by the IPCC is "sobering" says Mindy Lubber of Boston-based Ceres, a nonprofit that encourages and tracks corporate actions on sustainability.

Although the Trump administration in the United States symbolizes an apparent slowdown in government action on climate, the private sector may be a better barometer of where humanity is headed. And, although they have a long way to go, over the past year corporations have actually been stepping up the pace of their voluntary efforts to address climate change. The new report may if anything amplify that trend.

“Business and financial players understand that climate is an economic and business risk as well as opportunity,” says Ms. Lubber. “Things that we never thought possible five years ago, certainly we're seeing those changes.”

Almost one-fifth of Fortune Global 500 firms are now committed to the use of science-based targets for reducing their greenhouse-gas emissions. And they’re signing on at a pace that’s 39 percent faster this year than in 2017.

A business imperative?

No one is pitching corporate action alone as the solution. And indeed the corporations are taking action partly under pressure from governments, consumers, and environmental groups. But their rising urgency also stems from what many see as simple business calculation: A healthier planet means bigger market opportunities; and a less-hospitable planet, the reverse.

“We succeed when those around us succeed,” says Kevin Rabinovitch, global vice president of sustainability at Mars Inc., the candy company based in McLean, Va. “You can’t run a successful business in a failing economy or a failing environment.”

This goes hand-in-hand, he says, with the moral argument: Caring for the environment is “doing the right thing.”

His comments show how, for corporations, climate action increasingly intertwines the realms of risk-management, business strategy, and the more philanthropic “social responsibility” efforts.

A year ago Mars joined the Science Based Targets initiative. At leadership meetings, the company’s carbon-emission footprint is among the metrics on a dashboard, right alongside things like revenues and costs.

The trend among corporations is to enlist in collective and ongoing initiatives, not just to issue one-off press releases. Science Based Targets now has 492 companies committed. Another initiative, “We are still in,” represents US companies and local governments pledging to keep aiming for targets that nations agreed to in the 2015 Paris Agreement, despite President Trump’s pledge to withdraw the US from the accord. And RE100 is a group of firms aiming to rely 100 percent on renewable energy.

“This is a trend that’s been growing steadily,” says Kevin Haley, a manager at Rocky Mountain Institute’s Business Renewables Center, a Boulder, Colo., group that helps businesses move toward renewable energy and lower-emissions strategies. When the center was founded in late 2014, only about five companies had done large-scale renewables procurement, says Mr. Haley. Now that number is over 70. And more than 150 have taken the RE100 pledge to go to 100 percent renewable energy. (For more examples, see sidebar at bottom of the story.)

Steven Majoros, marketing director for General Motors’ Chevrolet division, says the firm’s participation in a new promotion of electric vehicles isn’t just about fitting in with a green-oriented state government in California. It’s about a wider vision of the business model that will resonate with consumers.

“We have clearly gone on record with our ‘zero, zero, zero’ long game strategy,” including zero greenhouse-gas emissions alongside the goals of eliminating fatal crashes and congestion from motorized transportation, he said during a telephone news conference last week.

“At the end of the day it does come down to creating market demand,” he adds, “to make sure people can see themselves with us on [this] journey.”

A global problem demands concerted effort

If the world is to achieve the 1.5-degree goal, or even hold warming to 2 degrees, the private sector will inevitably have to play a big role, say environmental experts and others. That’s because business accounts for such a large share of economic activity, and can be a fount of innovation. Meanwhile, many say government has a vital role in setting societal objectives, at a time when scientists say speed and scale are critical.

The new IPCC report suggests that, to hit the 1.5-degree goal without any initial overshoot, the world will need to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, say analysts at the World Resources Institute in Washington.

“Without engagement of the private sector in this, governments will fail,” predicts Mr. Rabinovitch at Mars. “And without government engagement the private sector will fail.”

A key goal, whether for government policymakers or for businesses, is not just to address the risks of a warming planet but also to do it in a way that allows humans to prosper.

So, for Caroline Krajewski, who heads corporate social-responsibility efforts at The Kraft Heinz Company, the goal of reducing emissions sits side-by-side with the company’s philanthropic efforts to feed malnourished children in India – a step that could not only reduce hunger but boosts that nation’s economic future by helping more people succeed in school.

And now the firm is working to set targets to reduce carbon dioxide emissions beyond its own factories.

“We found out that the majority of our carbon emissions were actually coming from our supply chains,” Ms. Krajewski says. “We’re in the very early stages, [but we’re] eager to build that strategy.”

Staff writer Amanda Paulson contributed to this story from Boulder, Colo.

Notable examples of corporate action:

- Retailer Target is among the leaders in moving toward 100-percent renewable energy, adding rooftop arrays on hundreds of its stores and investing in a Kansas wind farm.

- Food company Kraft Heinz moved to address deforestation last year by joining a broader effort to ensure that palm-oil supplies can be traced to locations with sustainable harvesting. Its palm oil is now all certified sustainable.

- Mars, a partner with Fairtrade International and the Rainforest Alliance on similar issues, last month said “the cocoa supply chain of today does not deliver on [the company's stated] ambitions.” It launched a $1 billion effort that includes using GPS to monitor forests in the supply chain.

- With Big Oil long a laggard on climate change, this week ExxonMobil said it would devote $1 million to lobbying for a US carbon tax or other incentives to reduce greenhouse emissions, adding money to what had been lukewarm support for the idea.

- Automaker General Motors just joined environmental groups to launch a California ad campaign pitching the benefits of electric cars and to overcome perceptions of the vehicles as green but costly or range-bound.

After historic Van Dyke verdict in police shooting, Chicagoans look to the future

To those advocating for police reforms in Chicago, the rare murder conviction for a Chicago cop is seen as a stepping stone toward a fairer justice system. What might come next?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Nissa Rhee Correspondent

Jedidiah Brown rushed to the courthouse when he heard that a verdict was imminent in police officer Jason Van Dyke’s trial for the shooting of Laquan McDonald. For the first time in 50 years, an officer was found guilty of murder for an on-duty shooting. “It looks like a new day in America,” said Mr. Brown, an organizer. But within minutes, he was focused on what comes next. “Now it’s time to get the reform.” The course of that progress is still uncertain. The City of Chicago and the Illinois attorney general have agreed to enforce reforms suggested by the Department of Justice after their investigation into the police department. That draft consent decree is currently open to public comment, and a judge will ultimately decide whether to approve it. Crime in Chicago has dropped in 2018, with the murder rate estimated to fall 23 percent by the end of the year, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. But relations between officers and communities like the one Laquan came from remain tense. “While the jury has heard the case and reached their conclusion, our collective work is not done,” said Police Superintendent Eddie Johnson, who called on the public and police to hear and partner with each other. “The effort to drive lasting reform and rebuild bonds of trust between residents and police must carry on with vigor.”

After historic Van Dyke verdict in police shooting, Chicagoans look to the future

At the front of a crowd of 200 people in Chicago on Friday, Antonio Magitt was still in shock. For the first time in 50 years, a Chicago police officer had been found guilty of murder for an on-duty shooting.

Many businesses and schools had closed early in anticipation of unrest following the verdict in the Jason Van Dyke trial and the streets were eerily quiet that afternoon, despite the marchers.

“I’m relieved,” Mr. Magitt, a youth organizer, said. “All of our hard work has paid off. This is progress.”

Magritt, a South Side native, said that he had been protesting on the streets since the release of the video in 2015 that showed Mr. Van Dyke shooting 17-year-old Laquan McDonald 16 times, and that he plans to keep organizing.

“As long as we keep doing this work, the Chicago police department will change for the better,” he said. “The city needs to start investing in our streets, instead of policing our trauma.”

The Laquan McDonald shooting rocked Chicago. It took more than a year of protests from journalists and activists for the city to release the dash cam video, and once it did, hundreds of people took to the streets again to demand justice.

The police superintendent was quickly fired. The Department of Justice came to town to investigate the police department. And Mayor Rahm Emanuel, a Democrat whose office was accused of covering up the shooting, announced he wasn’t going to seek a third term.

Now, the city is taking stock of the past four years and looking to the future.

A jury convicted Van Dyke of second-degree murder and 16 counts of aggravated battery. When the verdict was announced Friday afternoon, the crowd outside the criminal courthouse in Chicago erupted in cheers.

“It looks like a new day in America,” organizer Jedidiah Brown told a dozen activists who stood outside a police barricade. “Let’s go celebrate somewhere!”

Mr. Brown, like many who rushed to the courthouse when the judge announced a decision was imminent, has been organizing around police reform for years. Just minutes after hearing the verdict, his mind was on what’s next.

“Now it’s time to get the reform,” said Brown. “It’s time to change the policy. It’s time to change the people who are elected.”

A call for public-police partnership

In a statement Friday, Mayor Emanuel and Police Superintendent Eddie Johnson called on the public and police to hear and partner with each other.

“While the jury has heard the case and reached their conclusion, our collective work is not done,” said Mr. Johnson. “The effort to drive lasting reform and rebuild bonds of trust between residents and police must carry on with vigor.”

The course of that progress is still uncertain. The City of Chicago and the Illinois attorney general have agreed to enforce reforms suggested by the Department of Justice after their investigation into the police department. That draft consent decree is currently open to public comment, and a judge will ultimately decide whether to approve the decree. Adding to the uncertainty of the matter is the fact that both Emanuel and Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, who negotiated the consent decree, are not seeking reelection. Implementing it will be left up to their successors.

On Monday, President Trump cast doubt on reform and criticized a 2015 agreement made between the American Civil Liberties Union and the city to reform the police department’s use of “stop and frisk,” or investigatory street stops. The president said that he’s asked Attorney General Jeff Sessions’s office to “go to the great city of Chicago to help straighten out the terrible shooting wave.” “I’ve told them to work with local authorities to try to change the horrible deal the city of Chicago’s entered into with ACLU, which ties law enforcement’s hands, and to strongly consider ‘stop and frisk,’ ” said Mr. Trump, speaking to a gathering of law enforcement officers. “It was meant for problems like Chicago. It was meant for it. Stop and frisk!”

Crime in Chicago actually has dropped in 2018, with the murder rate estimated to fall 23 percent by the end of the year, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Shootings are down 17 percent for the first nine months of 2018, the Chicago Tribune reports.

But relations between officers and communities like the one Laquan came from remain tense. Some predict a backlash from the police after the verdict and increased resistance to reforms. On Friday, a representative from the Illinois police union threatened a work slowdown.

“This sham trial and shameful verdict is a message to every law enforcement officer in America that it’s not the perpetrator in front of you that you need to worry about, it’s the political operatives stabbing you in the back,” Illinois Fraternal Order of Police President Chris Southwood said in a statement. “What cop would still want to be proactive fighting crime after this disgusting charade, and are law abiding citizens ready to pay the price?”

But on Friday, some Chicagoans said they welcomed the message the verdict sent. Jermont Montgomery held back tears as he watched others rejoice outside the courthouse where the Van Dyke trial was held. Mr. Montgomery participated in the Black Friday march against police brutality in 2015 that shut down Michigan Avenue and cost retailers 25 to 50 percent of their sales in the normally busy shopping district.

“Laquan McDonald right now represents everyone,” Montgomery said. “Every last one of these officers and everyone across the nation will know now you can’t just take our lives without repercussions.”

‘We have to deal with the culture’

On the West Side, where Laquan grew up, news of the verdict spread quickly. The area has become a flashpoint for police reform, with a $95 million proposed police academy sparking clashes between protesters and politicians.

The plan for the academy was developed after the Department of Justice found that the police department’s current training facilities were woefully inadequate. Critics argue that the money used for it could be better spent on schools and social safety nets. Chicago spends 39 percent of its budget on policing, almost five times the portion New York City spends.

Marshall Hatch is pastor of New Mount Pilgrim Church, just a mile away from the site of the proposed training facility. He called the Van Dyke verdict “good and just,” though he says he feels bad for Van Dyke’s family.

“Our attention goes now to the consent decree,” says the pastor. “The consent decree gives us an opportunity to deal with the protocols of the police department and how police are tracked and supervised. We have to deal with the culture.”

Mr. Hatch said that he is concerned about what the impact of a police slowdown would be for his neighborhood, which already suffers from a high level of gun violence.

“That will leave everyone in danger,” he said.

Instead, he hopes that the police will respect the verdict.

“I think we need to move on now. Some of us are ready to focus on radical reform of the police department. It’s a long, long road ahead.”

Venezuela crisis: In Latin America, a surge in tough rhetoric on borders

Could the anti-immigrant nationalism of Europe find a similar foothold in Latin America? Waves of Venezuelan refugees are raising fears – and hardening positions – among Venezuela’s neighbors.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When it comes to Venezuela, more Latin American countries are sounding like the Trump administration, which has pointedly said “all options are on the table.” The hardening tone, regional experts say, reflects mounting concerns that the reverberations of Venezuela’s collapse could destabilize the region if unaddressed. Chief among the fears is that the humanitarian crisis leading to the arrival of thousands of destitute refugees could spawn nationalist political movements, potentially setting back Latin America’s embrace of democracy and rising prosperity. But if South American countries are talking tough, some say, they are carrying very little in the way of a stick, as even Washington has little appetite to do much beyond the sanctions it slaps on members of President Nicolás Maduro’s government. “Latin America without the US is not going to make any meaningful changes in Venezuela,” says Eric Farnsworth, vice president of the Americas Society and Council of the Americas in Washington. On the other hand, he says, a worsening migration crisis could prompt actions that could increase political upheaval. “These countries just don’t have the capacity to absorb these refugee flows, so at some point something is going to snap.”

Venezuela crisis: In Latin America, a surge in tough rhetoric on borders

Vice President Mike Pence knows first-hand about the shift among South American countries to a more interventionist approach to Venezuela’s economic collapse and deepening – and spreading – humanitarian crisis.

Far less clear, some regional experts say, is whether a tougher stance toward Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro gives Latin American countries any leverage to force changes in their collapsing neighbor.

A year ago when Mr. Pence stopped off in Bogotá as part of a swing through the region, his hint that the United States included military force among its “many options” for addressing Venezuela’s “tragedy of tyranny” met with a stern retort from then-Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos.

“Since friends must tell [friends] the truth, I have told Vice President Pence the possibility of military intervention shouldn’t even be considered,” Mr. Santos said.

But that was then.

At the United Nations two weeks ago, Pence attended a special meeting called by Colombia’s new president, Iván Duque, on South America’s expanding refugee crisis spawned by Venezuela’s downward spiral. He couldn’t have helped but notice the shift.

Mr. Duque – who earlier in September had refused to sign on to a declaration of regional leaders opposing any use of force to end Venezuela’s crisis – pulled no punches in asserting that the “dictatorship” of Mr. Maduro must be brought to an end. And he thanked Pence for cautioning the Venezuelan government not to “intimidate” its neighbors, which have already received nearly 2 million Venezuelans fleeing their country’s dire straits.

Colombia’s embrace of a hard-line approach to Venezuela reflects a broader shift across Latin America to more interventionist rhetoric as the region grows increasingly alarmed at the spillover from their neighbor’s humanitarian and political crisis.

President Trump, in his speech to the annual meeting of the UN General Assembly in September, took a moment to slam Maduro and his destruction via “socialism” of a once-wealthy country.

Yet while virtually no one sees Mr. Trump’s insistence that “all options are on the table” actually leading to a US military invasion to topple Maduro, some regional experts say the hardening tone reflects mounting concerns that the reverberations of Venezuela’s collapse could destabilize the region if unaddressed.

What the crisis could beget

Among the fears: that the humanitarian crisis and arrival of thousands of destitute refugees could spawn nationalist political movements and foment regional tensions, potentially setting back Latin America’s embrace of democracy and rising prosperity.

“We hear more and more ideas like mass deportations of Venezuelans and claims of the crime and poverty they are bringing with them,” says Brian Fonseca, a Latin America expert and director of the Gordon Institute for Public Policy at Florida International University in Miami. Such ideas, he says, are “a ripple effect of this crisis that some are worried has the potential to really shift the political discourse in their countries and feed an angry backlash and nationalist movements.”

“If there’s an increasingly hard line on Venezuela and urgent regional demands for answers to its crisis,” he adds, “it is in part because some leaders and others believe we could wake up in a decade and see some serious social and political fractures shaking the region – and could trace it back forensically to the Venezuela crisis.”

To illustrate the kind of political impact that South America’s “migration crisis” could have, Mr. Fonseca cites the Mariel boatlift of 1980, which resulted in more than 125,000 Cubans leaving for South Florida over a matter of months.

“Florida and indeed US politics are still feeling the impact of that migration today,” he says, “and I don’t think it’s exaggerating to consider a potential impact of double that or more” from Venezuelan migrants arriving across South America.

Already more than 1 million Venezuelans have fled to neighboring Colombia, with as many as 5,000 more arriving each day, according to the Colombian government. Another 400,000 are in Peru, with smaller numbers arriving in Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Mexico – and Florida.

Another reason for the shift in thinking toward Venezuela is that the socialist revolution declared by Mr. Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, has lost ideological soulmates in the region, Fonseca says. At the same time, a number of less confrontational leaders have been replaced with others espousing a more interventionist approach. Colombia’s switch from Santos to Duque is a case in point.

“At one point you had allies of Venezuela across Latin America. Maduro could count Argentina, Peru, and Ecuador among his friends, but that’s pretty much dried up,” Fonseca says – citing Bolivia and Nicaragua as exceptions.

Shift not lost on Venezuela

Indeed Venezuelan officials are well aware of the regional shift in attitude.

After the country’s foreign minister, Jorge Arreaza, was barred from entering the meeting Colombia hosted at the UN on the migration crisis and featuring the American vice-president, he blasted his neighbors attending the meeting as “gobiernos sicarios” – hitmen governments – carrying out Washington’s violent agenda toward Venezuela.

The same day Mr. Arreaza made the “hitmen” comment, five South American countries plus Canada signed a petition to the International Criminal Court asking that it investigate the Maduro government for “gross human rights violations” including murder, torture, and forced disappearance.

Yet while others agree that more Latin American countries are sounding more like the Trump administration when it comes to Venezuela, they add that in truth Washington has little appetite to do much beyond the occasional sanctions it slaps on members of the Maduro government (as it did again last week).

That leaves South American countries talking tough, but carrying very little in the way of a stick, they add.

“Latin America without the US is not going to make any meaningful changes in Venezuela, they don’t have the leverage and they don’t have the political will to take actions that could compel a change in behavior,” says Eric Farnsworth, vice-president of the Americas Society and Council of the Americas in Washington.

On other hand, he agrees that a worsening migration crisis could prompt actions that could increase tensions and political upheaval. “These countries just don’t have the capacity to absorb these refugee flows, so at some point something is going to snap.”

The Florida angle

Venezuela has indeed lost regional friends over the past year, Mr. Farnsworth says. But he also notes that the “Maduro regime” has survived longer than many predicted – and he wonders if it might hold on long enough to see Latin America return to a more traditional perspective of non-interference in neighbors’ affairs.

“There’s no doubt that Latin America has moved incrementally closer to an uncharacteristic interventionist stance – in part as a result of a new crop of leaders – and that this movement has sped up with a humanitarian crisis that is affecting all these countries’ interests,” Farnsworth says. “But the question now is whether anything meaningful happens to change Venezuela’s course before the political pendulum swings again.”

Could such a swing even include Trump? Fonseca of Florida International notes that at the UN the president floated the idea of meeting with Maduro to, in Trump’s words, “take care of Venezuela” – and he wonders if Trump might have another “North Korea-type initiative” up his sleeve.

If so, Fonseca cautions that Florida politics are sensitive enough to Venezuela’s calamity and Maduro’s grip on the country that Trump would face a very narrow window for a Venezuela diplomatic gambit that could appear unseemly to expat Venezuelans and other Latino voters in the Sunshine State.

“It would have to be after the midterms, of course, but it would also have to come well before 2020,” he says. “No one can afford to write off the state of Florida.”

Letter from the Capitol

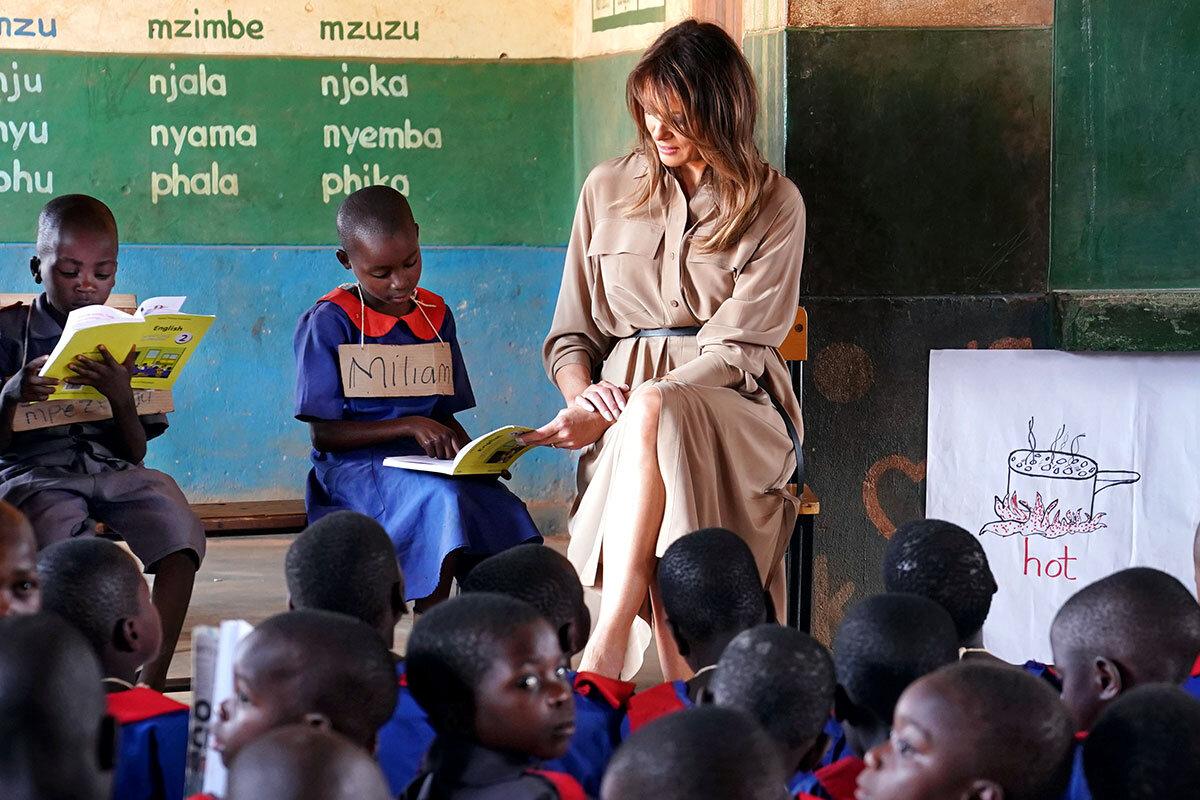

Aspects of Africa that the first lady could have seen

Living and reporting in Africa, Ryan Lenora Brown writes, is a daily process of “unlearning” – of learning to see beyond the one-dimensional stereotypes about the continent.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Four days into a trip to Africa, Melania Trump donned a white pith helmet – the domed, buckled hat fashionable among European colonists. Immediately, critics were aghast. But as I watched and read along from my home in Johannesburg, South Africa, I felt a flicker of sympathy for the first lady, whose outfit mirrored most Americans’ knowledge, or lack thereof, about Africa: a continent often portrayed as a ready-made backdrop for American goodwill, with round-faced babies, orphaned elephants, and overcrowded classrooms. And I wished I could take her on a different kind of African jaunt. To the artists’ workshops of Accra, Ghana. To talk with the powerhouse, prizewinning runner who has given away her money just as quickly – and underscored that philanthropy can be homegrown, too. To enjoy the quintessentially West African experience of sitting in wheezing peak-hour traffic and watch as hawkers stream by your car with a supermarket of goods balanced on their heads: Donuts! Air fresheners! Inflatable pools! I wish, in short, she could have seen Africa as I am privileged to be able to see it every day – as a staggeringly diverse and maddeningly complicated place. For me, unlearning the things America taught me about Africa will probably be a lifelong endeavor. Perhaps this trip – and that hat – will be the start of Mrs. Trump’s own.

Aspects of Africa that the first lady could have seen

As first lady Melania Trump zig-zagged across Africa last week, the trip, at first, seemed largely without fanfare.

She held round-faced babies at a Ghanaian hospital and doled out books and soccer balls at an overcrowded Malawian school. She listened in solemn horror as a guide told her the history of Cape Coast Castle, a slave fort in Ghana, and laughed as she was nearly knocked over by a baby elephant she was bottle-feeding at a sanctuary in Kenya.

And then she put on the hat.

As Mrs. Trump prepared to board the safari vehicle that would take her on a jaunt through Nairobi National Park last Friday, she donned a white pith helmet – the domed, buckled hat fashionable among European colonists in Africa and Asia. (Think Meryl Streep in “Out of Africa.”)

Immediately, the internet was aghast. Had the first lady just made a sartorial nod to the good old days of colonialism, in full view of the world?

The next day, in front of the Egyptian pyramids at Giza, she tried to redirect the conversation.

“I want to talk about my trip and not what I wear,” Trump told the huddle of reporters traveling with her. “That’s very important, what I do, what we’re doing with [development agency] USAID, my initiatives and I wish people would focus on [that].”

In a sense, Trump was right to be irked. Critics had been looking for days for clues that the first lady didn’t really care about Africa, a region that her husband has mostly ignored – and occasionally mocked – during his presidency. They scrutinized her scripted visits to schools, tourist sites, and presidential palaces, where she was a quietly graceful visitor whose most common utterance seemed to be, “Thank you for having me.”

As a reporter working in Africa, I felt a flicker of sympathy for the first lady. Her choice of hat had been deeply silly, offensive even. But it likely was a gesture of ignorance, not malice. It simply mirrored the knowledge level of most people in the country where she lives – people for whom the helmet’s history was so unknown that it simply wouldn’t occur to them that she shouldn’t wear it.

Similarly, we often talk about Africa in such sweeping, at-arms-length terms that we might not pause when even thoughtful journalists refer to a country she visited, Malawi, as “obscure.” (Obscure, one wonders, to whom?) Or when all of Africa – a continent of 50-some countries and a billion people – is referred to as “vast and impoverished,” or when people who live there are “beloved and admired for having deep joy and resilience, in the face of issues like widespread poverty, disease and technological isolation, as is seen in some African countries.”

Indeed, one of the hardest things for me about reporting on this continent is that we are given a tacit permission to be simplistic, because few people challenge that view. And each time a figurehead visits to do charity and look at wildlife, they reinforce these perspectives. I suspect that Africa has long been a popular destination for first ladies, in particular, because it seems on the surface like a ready-made backdrop for American goodwill. It looks, from some angles, like an entire continent full of poor people and poor countries eager to be on the receiving end of American goodness. Often, as in Trump’s case, those recipients are children, a particularly sympathetic group. (Her trip was built around the “Be Best” campaign promoting children’s well-being.)

As I watched Trump’s trip from my home in Johannesburg, I wished that I could take her on a different kind of Africa jaunt. In the Ghanaian capital, Accra, for instance, I might have suggested she duck out of the presidential palace and pay a visit to a few artists’ workshops in the neighborhood of Teshie. There, she could have seen the sometimes wacky, sometimes profound whimsicality of the country’s famous coffin builders, who sculpt caskets in shapes ranging from cola bottles to lions to human-sized cell phones. In Kenya, instead of packing her day with visits to orphanages – first one for elephants, then one for humans – Trump could have taken a detour to the outskirts of the capital to meet Tegla Loroupe, a tiny powerhouse of a woman who broke nearly every distance running record in the world, and when she finished doing that, just as quickly began giving the money away. (Philanthropy, Trump could have pointed out to the Americans watching back home, can be homegrown, too.)

I think she might have even enjoyed the quintessentially West African experience of sitting in wheezing peak-hour traffic instead of speeding around it in her motorcade, watching as hawker after hawker streams by your car with a veritable supermarket of goods – donuts! Air fresheners! Inflatable pools! – balanced on their heads. The whole thing might have been a reminder of how hard and how creatively people work to survive any place where the system seems stacked against them.

I wish, in short, she could have seen Africa as I am privileged to be able to see it every day – as a staggeringly diverse and maddeningly complicated place. For me, unlearning the things America taught me about Africa will probably be a lifelong endeavor. I am still surprised by my own surprise at hearing, for instance, that Rwanda has three times the percentage of female legislators as the United States, that eastern Congo is well known for its cheesemakers, or that a bunch of teenage girls in South Sudan can kick my butt at dodgeball. Believing that a society or country or community can be many things at once – some of them dissonant and contradictory – is a privilege we grant freely to the places we come from. So why can we not also hold multiple Africas in our head as well?

The Africa Melania saw last week wasn’t fake. There are, in many countries on this continent, too many children crowded into underserved schools. There are too many animals being killed by poachers. There are too many dying babies.

But there are also artists and philanthropists and complicated, contradictory societies stumbling forward in the world. The same as in the United States. The same as everywhere.

Perhaps this trip – and that hat – will be the beginning of Trump’s own unlearning. If so, she and I are in that together.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A Nobel for ennobling ingenuity

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Economist Paul Romer proposed decades ago that societies look beyond the material drivers of long-term growth. Economic progress, he showed by dint of data, relies more on how well a society manages an intangible good: the discovery of new ideas that propel innovation. On Monday, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. (He shares it with Yale University’s William Nordhaus, who won for being the first to calculate links between the economy and the climate.) Romer’s influence can be seen today in the worldwide chase among nations to build an “innovation economy” by beefing up research and guarding intellectual property. Innovation must be managed and promoted to bear fruit. On climate change and the need to reduce carbon emissions, for example, Romer believes that once governments provide the right incentives for innovation in energy research, “We will be surprised that it wasn’t as hard as we anticipated.” As Romer puts it, “Possibilities do not add up. They multiply.” Long-term economic growth as well as solutions for climate change can be found in understanding how to tap the many ideas as yet undiscovered.

A Nobel for ennobling ingenuity

In scholarly work done more than three decades ago, economist Paul Romer proposed that societies look beyond the material drivers of long-term growth, such as oil, ports, or labor. Economic progress, he showed by dint of data, relies more on how well a society manages an intangible good: the discovery of new ideas that propel innovation.

Dr. Romer, now at New York University, especially focused on ways to reward people who come up with useful ideas in technology or management. He challenged fellow economists by asking questions like “What is the value of an idea?”

On Monday, Romer himself was rewarded for his work. He won the Nobel Prize in economics. (He shares the prize – and its $1 million reward – with Yale University’s William Nordhaus, who won for being the first to calculate links between the economy and the climate.)

Romer’s influence can be seen today in the worldwide chase among nations to build an “innovation economy.”

Many countries now vie for start-ups and bright students. They beef up basic research. They are more aggressive in guarding intellectual property, reflected in the current “trade war” between the United States and China. They promote creativity, curiosity, and freedom of thought. They idolize great inventors and innovators.

In the past, Romer says, countries practiced a “complacent optimism” toward new ideas, from the cotton gin to assembly-line manufacturing to driverless vehicles. They saw inventions as something that mostly just happened and are external to the main task of adding “more inputs” of workers, natural resources, and capital to gain “more outputs.”

“Every generation has underestimated the potential for finding new ... ideas,” he wrote. “We consistently fail to grasp how many ideas remain to be discovered.”

Yet innovation must be managed and promoted (such as in the awarding of prizes like the Nobels). Romer’s approach is perhaps best summed up in his famous saying, “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste.”

On climate change and the need to reduce carbon emissions, for example, he believes that once governments provide the right incentives for innovation in energy research, “We will be surprised that it wasn’t as hard as we anticipated.”

In the US today, industries that rely intensively on patents and other intellectual property account for more than a third of the gross domestic product. Their growth outpaces industries that rely little on intellectual property. As Romer puts it, “Possibilities do not add up. They multiply.”

In other words, long-term economic growth as well solutions for climate change can be found in understanding how to tap the many ideas as yet undiscovered.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

When problems seem overwhelming

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Jenny Sawyer

Today’s column explores the idea that God, divine Love, is “big” enough to meet every need, to fill every void, to comfort every heart, including those struggling with dark or suicidal thoughts.

When problems seem overwhelming

A while ago, I found out that a friend from my high school days had committed suicide. Though she wasn’t someone with whom I was still close, the news was shocking and saddening. Perhaps more distressing was the fact that she isn’t the first person I’ve known who has taken her own life, and this realization impelled me to pray about suicide in general. I’ve found that when an issue seems overwhelming, prayer helps me move beyond the magnitude of the problem to see things from a new perspective.

For me, in this case, the thought that sometimes there really is no answer and no way out was the thing I felt I needed to pray about. And the inspiration that came to me was the idea that no problem is too big for God because of God’s infinity – that God, infinite Mind, must include every answer, every solution, to every conceivable problem. Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, articulated this simply and beautifully when she wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” using Love as another name for God, “Divine Love always has met and always will meet every human need” (p. 494).

That was a great starting point, but it also got me wondering: What does “infinite” really mean? It’s one thing to say Mind or Love is infinite, but I felt like I got that only in an abstract way. I wanted to understand it so I could feel with total conviction that no matter what situation someone found him- or herself in, there would always be a solution because of the infinite nature of God.

Fast-forward a few weeks to a morning when I was away on a trip and woke up to a stunning view of the ocean. From my room, I could see the first streaks of light glinting along the horizon and radiating across what seemed like an endless expanse of water. Pink changed to gold and then to almost white, and suddenly the whole sky was illuminated, with the limitless blue of the ocean stretched out and shimmering below.

I suddenly felt, in a way I never had before, the meaning of big. The feeling, a sense, of infinite. Looking out at that water that seemed to go on forever, I thought about how that expansiveness only hinted at the expansiveness – or, really, the limitlessness – of the Divine.

It’s not a perfect analogy, of course, but I could see how if that ocean hadn’t been water but the expansive presence of Love itself, I would understand it and never doubt again that divine Love was “big” enough to meet every need, to fill every void, to comfort every heart.

I think in that moment, the idea of infinite changed from a head thing to a heart thing. Instead of just thinking about it, I actually felt something of the absolute vastness of divine Love, and I really knew deep down that it included everyone, in every circumstance, everywhere. This is something I’ve continued affirming for the people I love as well as for those I don’t know who might be struggling with dark or suicidal thoughts.

Suicide is something I want to keep praying about, and I hope you’ll join me. Together, let’s understand in a deep-down way that troubled teenagers, desperate 20-somethings, or anyone who feels hopeless can sense and feel something of the “oceans” of love God has for each of us. The depths of His care. The divine Mind’s limitless intelligence to match and overcome even the most vexing problems. Time and again I’ve experienced that prayer does make a difference. It can free any of us from the lie that our problems are too big for infinite Love.

Adapted from an article published in the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, Oct. 7, 2016.

A message of love

Standing on others’ shoulders

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about a recent election in Quebec, and the message it sends about the quest for independence.