- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

To Mars and beyond

Yes, the latest Mars probe deserves all the accolades heaped upon NASA for its successful landing Monday (only 40 percent of all Mars missions are a success). But spare a round of applause for two tiny spacecraft escorting InSight along the 301-million-mile journey.

The two Mars Cube One satellites, dubbed MarCO-A and MarCO-B, are each not much bigger than a briefcase. But the Lilliputian twins made history as the first CubeSats to venture out of low-Earth orbit into deep space. More significantly, they pioneered a new model for relatively inexpensive interplanetary communication.

Until now, when NASA wanted to talk to a Mars probe, they’ve repositioned a large research satellite already in orbit around the Red Planet. This time, the 800-pound InSight brought its own comms team. As the lander descended to the planet (a cosmic braking maneuver known as “seven minutes of terror”), the MarCOs circled above, relaying data about InSight’s status back to mission control in California within just eight minutes – a process that on previous missions had taken up to three hours. CubeSats: Faster, cheaper, and more nimble.

“MarCO,” one NASA engineer told IEEE Spectrum, “is a pathfinder for future missions.”

As the InSight probe starts its seismic study of Mars, the MarCO twins will continue on an elliptical orbit around our sun, once again going where no CubeSat has gone before.

Now to our five selected stories, including the transforming nature of generosity, the enduring power of Canadian goodness, and the role of leadership on climate change.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why President Trump may want a ‘good shutdown’

If Congress can’t agree on issues such as funding for a border wall, key parts of the government could shut down. We look at why the president may see an opportunity in creating a crisis.

As the final, lame-duck portion of the 115th Congress begins, and Republicans enter their waning days in control of the House, the possibility of a partial government shutdown is looming. President Trump speaks of a shutdown regularly, as a way to sharpen the stakes of a tension-filled border debate and to please his political base. A shutdown in early December would actually involve only one-quarter of the government, as most departments are already funded through September 2019. But among those awaiting funding for next month is the Department of Homeland Security, which includes the Border Patrol – and congressional negotiations have bogged down over money for Mr. Trump’s long-promised border wall with Mexico. Funding for the Justice Department would also expire in a shutdown, giving Trump the power to decide if special counsel Robert Mueller is an “essential” employee and therefore still able to work. Still, Republican strategist Rick Tyler, a Trump critic, finds all the shutdown talk odd. “I’ve never known anybody to advocate for a shutdown,” Mr. Tyler says. “Because a shutdown is really a failure of leadership on both sides. A leader’s job is to find common ground and get an agreement.”

Why President Trump may want a ‘good shutdown’

Since the early days of his presidency, Donald Trump has been talking about shutting down the very institution he campaigned to lead: the federal government. Sometimes he frames such a move as a “good shutdown,” much the way people used to talk about a child needing a “good spanking.”

The goal of a “good shutdown,” President Trump tweeted last year, was to fix the “mess” in Washington. Since then, the federal government has shut down twice, as congressional funding has lapsed, but so briefly as to be hardly noticeable. And certainly, Washington still isn’t performing as Mr. Trump would like. For one, Congress still hasn’t funded his long-promised border wall with Mexico.

Now, as the final, lame-duck portion of the 115th Congress begins, and the Republicans enter their waning days in control of the House, the possibility of a partial shutdown looms. Funding for several critical departments is due to expire Dec. 7. Trump speaks of a shutdown regularly, as a way to sharpen the stakes of a tension-filled border debate, please his political base, and set up the politics of 2020 with a slam on Democrats as soft on migrant caravans full of “criminals.”

For GOP legislators, there’s a big downside to headlines about a “government shutdown.” During the lame duck, they will still control both houses of Congress. It’s their last chance to show that Republicans can govern constructively, with both the legislative and executive branches in their hands.

Still, for Trump, the timing may be right for a “good shutdown,” say Republicans sympathetic to the president. The next general election is nearly two years away, and so memories of any negative fallout would fade. And for Trump supporters, a shutdown would show a commitment to one of his core campaign promises, still a sure-fire chant at rallies: “Build that wall!”

“If he’s going to go all in for the border wall, this is the best time to do it,” says Republican strategist Ford O’Connell.

A “shutdown” in early December would actually involve only one-quarter of the government, as most departments are already funded through September 2019. Among those departments awaiting funding is the Department of Homeland Security, which includes the border patrol. Though as with all shutdowns, agency heads are empowered to exempt “essential personnel,” so the critical functions of government – including border security – would not stop.

In short, to most Americans a “shutdown” would be largely notional – albeit disruptive to furloughed government employees and not without costs to the economy, but a headline that Trump may feel works to his advantage. And besides, the former reality TV star president seems to love drama.

Sticking points

Negotiations on government funding have bogged down over issues that include funding for border security. Senate legislation provides $1.6 billion, while the House bill allocates $5 billion. The Senate bill has support from members of both parties, while the House bill is built just on GOP votes. Trump has argued for as much as $25 billion in wall funding, but the final number is likely to come in closer to the Senate figure than that in the House, according to reports.

For all concerned, the optics are key. No Republicans in Congress are rooting for a shutdown, but some are more willing than others to make Trump’s case about the US-Mexico border.

“Look, this is a national security interest of ours,” Rep. Mike Johnson (R) of Louisiana, incoming chair of the conservative House Republican Study Committee, said Sunday on Fox News. He cited human traffickers, drug cartels, and “radicalized terrorists coming across the border undetected.”

Still, Congressman Johnson predicted that a government shutdown wouldn’t be necessary to get the funding needed to secure the border.

Democrats are already framing their arguments for the inevitable blame game, should a shutdown occur.

“If the president of the United States, who already is a historically unpopular president, is seen as causing the inconveniences and other problems associated with a government shutdown, it's going to be a real political problem for him,” Rep. Jim Himes (D) of Connecticut said Sunday on Fox News. “It won't be the Democrats in the House of Representatives that are shutting down the government. It'll be the president.”

Democrats, in a way, have the best of both worlds. They can block legislation in the Senate by filibustering, which requires 60 votes to overcome (the GOP currently has a 51-49 majority in that chamber). But the image in Washington is of a Republican Party with total control, and so it may be easy for Democrats to convince the public that the GOP, with Trump in charge, is to blame.

The importance of optics

Some 55 percent of registered voters (and 34 percent of Republicans) do not support a shutdown over the border wall, according to a poll by Morning Consult. Democrats have floated the idea of legislation to protect special counsel Robert Mueller and to eliminate a question on the next census about citizenship as bargaining chips. But Morning Consult found a 47 percent plurality said a bill protecting Mr. Mueller’s job wasn’t worth shutting down the government. The poll didn’t ask about the census.

Another wild card is that funding for the Justice Department would expire in a shutdown, and Trump would have the power to decide if Mueller is an “essential” employee and therefore still able to work. Employees deemed “nonessential” are not allowed to work during a shutdown.

Trump seems unfazed by public opinion on a shutdown. And when asked by reporters, Trump repeats his willingness – at times enthusiastically – to shut down the government over border wall funding.

“This would be a very good time to do a shutdown,” Trump told reporters at the White House before Thanksgiving, adding that he didn’t think it would be necessary. “I think the Democrats will come to their senses, and if they don’t come to their senses, we will continue to win elections.”

Republican strategist Rick Tyler, a Trump critic, finds all the shutdown talk odd.

“I’ve never known anybody to advocate for a shutdown,” Mr. Tyler says. “Because a shutdown is really a failure of leadership on both sides. A leader’s job is to find common ground and get an agreement, based on a win-win.”

Democratic strategist Jim Manley also sees the shutdown talk as a nonstarter.

“Unless the president gives up a lot in the upcoming negotiations, he’s not getting the $5 billion for his beloved border wall,” says Mr. Manley, former spokesman for retired Democratic Senate leader Harry Reid. “Democratic leaders would be run out of town if they agreed to that.”

But the real negotiations haven’t started yet. And nothing will be decided until the last moment, as usual. If Trump really wants to get some mileage out of a “good shutdown,” if only with his existing supporters, Tyler says, he’ll have to make a big deal out of it.

“I don’t think [House Democratic leader] Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats are afraid of a shutdown, because most people don’t notice it,” Tyler says. “He’d have to make a spectacle of it to get it even noticed. But my guess is if it’s going to be about a blame game, which Trump wants, two-thirds will blame him and one-third will blame her. I’d take those odds.”

Editor’s note: Congressman Johnson’s office reached out Nov. 29 to clarify a statement he made Sunday on Fox News that seemed to suggest he supported a shutdown over border security funds. Johnson issued the following statement: “Clearly we do not want a government shutdown, and thankfully, I don’t think it will come to that. I expect the president will get the wall funding he has been asking for the past two years, and I fully support the wall as a necessity. This is a national security issue, and it is imperative we secure our borders and protect the American people.”

Patterns

COP24: nationalism and the challenge of climate change

At a world gathering on climate change this weekend, nations will face a key political test: whether they can transcend the narrowness of nationalism in favor of cooperation. All eyes will be on the US and China.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

For participants in a major international meeting next week in southern Poland, the central task is daunting enough: Draw up a rulebook to implement the 2015 Paris Agreement’s aim of dramatically slowing climate change. But the real test will be whether, in a world increasingly driven by nationalism, there’s enough international political will for any effective response to the borderless problem. Despite the declared aim of the agreement to limit the rise in global temperatures, in large part by phasing out coal, there was a pragmatic recognition that targets agreed to by individual nations would not be mandatory. That was one tradeoff for getting less developed economies on board. The meeting in Poland is meant to achieve the next best thing: agreement on a robust system of reporting to ensure that countries are meeting their commitments. But reports have indicated that the Trump administration – never a willing party to Paris – will promote the long-term potential for “clean coal” rather than reveal plans for eliminating coal power over the coming decades. And China still appears positioned to argue that the US and Europe, the main source of carbon emissions in the past century, bear responsibility for leading the transition.

COP24: nationalism and the challenge of climate change

Two major international meetings are about to take place, and the first – the G20 summit of the world’s leading economic powers – is likely to grab the lion’s share of the headlines. But it’s the second, opening this Sunday in the southern Polish city of Katowice, where the stakes are greater.

At issue is climate change. The task at COP24 is to draw up a rulebook to implement the 2015 Paris Agreement’s aim of dramatically slowing it down, and averting what scientists increasingly agree is the alternative: hugely damaging natural, economic, and human costs across the globe.

That’s likely to prove daunting enough. But the real test will be whether the international cooperation and political will necessary for any effective response to climate change, a process that does not recognize state borders, is possible in a world increasingly driven by narrower nationalism. That’s especially true of two key players: the United States and China.

A series of scientific reports ahead of Katowice has underscored how far governments still have to go if they’re to reach the stated goal of Paris – limiting global warming to “well below” 2 degrees C or 3.6 degrees F. more than pre-industrial levels – and how dire are the potential consequences of failure. The most comprehensive of the studies, by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, concluded that even keeping the increase to 2 degrees wouldn’t avert the risk of punishing increases in extreme weather conditions, more droughts and flooding, and related threats of hunger, poverty, mass migration, and resource-driven wars.

The authors also warned of possible tipping points, such as an end to the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean, which could make the effects of climate change irreversible if concerted action weren’t taken over the next decade.

Although President Trump has played down the issue of climate change, a US government report last week also delivered a bleak assessment. With the continental US already 1.8 degrees F. hotter than a century ago, it noted that mountains in Western states were already seeing less snow and that wildfires like the blaze that recently destroyed thousands of homes and claimed dozens of lives in California were becoming more frequent.

Katowice’s challenge won’t primarily involve the science, however. It’s political.

Despite the declared aim of the Paris Agreement to limit the rise in global temperatures, in large part by phasing out emissions from coal, there was a pragmatic recognition that targets agreed to by individual nations would not be mandatory. That was one tradeoff for getting less developed economies, and crucially China, to participate in an international climate-change agreement for the first time.

The meeting in Katowice is meant to achieve the next best thing: agreement on a robust system of reporting to ensure transparency over whether countries are meeting their commitments as part of the global response to climate change.

While US leadership was a key in the Paris agreement, Mr. Trump has formally declared he intends to pull out. Since that can’t take effect for another year, he is still sending a delegation to Katowice, and in the run-up to the meeting, these experts and officials are understood to have been active participants in the search for an agreement. But news reports have indicated Washington will also send a team to make a presentation about the long-term potential for “clean coal,” rather than essentially eliminating coal power over the coming few decades as agreed in Paris.

China has been more active in pre-Katowice discussions than in past climate talks, in part perhaps as a pointed effort to demonstrate it is filling a leadership vacuum left by the US. Its own long-term economic plans also include a major focus on clean-energy technology.

But despite having the world’s second-largest economy, the Chinese still appear to be positioning themselves as one of the developing countries, which have tended not just to seek looser national targets. They’ve argued that countries like the US and European states, the main source of carbon emissions in the last century, need to bear the principal financial responsibility for their transition to cleaner energy – one of Trump’s principal objections to the whole Paris Agreement process.

[Editor's note: An earlier version of this story miscalculated the conversion of a 2 degree C change in temperature to Fahrenheit. It is 3.6 degrees F.]

Philanthropy

It’s a wide world of charity out there. Do you know how to navigate it?

It’s ’Giving Tuesday,’ the generous antidote to frenetic ‘Black Friday.’ This story offers tips for giving, including how to choose charities that spend your donation effectively.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Following all the Black Friday or Cyber Monday retail activity, today is widely promoted on social media as #GivingTuesday. It’s a helpful reminder of the call to give beyond one’s own family in the holiday season. But there’s actually no pressure to make your charitable donations on a particular day. The Monitor recently talked with experts for some tips on how to give, and one common refrain is that it pays to do some homework first. What needs are most urgent? What nonprofits are doing effective work? Below the expanded article you’ll find a sidebar with resources to help answer these questions. Taking a methodical approach can also help you avoid scams. Even if you don’t have much or any spare money, there are still ways to give. And Benjamin Soskis, an expert on philanthropy at the Urban Institute, says your engagement can be important as a democratizing force. He says the wealthiest donors are influential but don’t have all the answers, so there’s need for a “more grass-roots oriented, participatory approach” to charity.

It’s a wide world of charity out there. Do you know how to navigate it?

Giving can seem more complicated than ever: The world’s needs are vast, the number of nonprofits keeps rising, and some popular charities turn out to be havens of fraud or abuse. Then there’s technology, which has enabled a proliferation of “donate now” messages. Still, technology has given people new opportunities to make a donation.

Q: Where should aspiring donors start, in thinking about how to make their charitable dollar do the most good?

People who are asking that question are on the right path, say many experts on nonprofits. To give involves the “heart,” and doing so wisely involves the “head.” Those tendencies figure into two seemingly opposite trends in recent years. First, research has documented that the most effective appeals for money are usually directed straight at people’s emotions, often by focusing attention on a particular person in need. But second, a rising breed of wealthy philanthropists has been pushing for a more data-driven, results-oriented model of giving. That attitude has been rippling beyond the ultra-wealthy.

“Donors are asking more questions about effectiveness than ever,” says Stacy Palmer, editor of The Chronicle of Philanthropy. This mindset has spread from tech-industry moguls to average givers, she says.

The problem is that tracking and evaluating charities’ results is in many ways still in its infancy. “One of the things that frustrates a lot of donors is there’s just not a lot of great information you can find,” Ms. Palmer says, “to figure out who is really effective at making a difference.”

There’s no one template for potential donors. Give mostly locally, where one can observe the effects directly? Give globally, where each dollar may go further? Answers to such questions will vary. But it’s taking a big step just to think them through.

Giving USA

Q: How can the choices for giving be narrowed down?

A common approach is to start by asking which causes you believe are most important to support, and then do research to find specific organizations you trust to be effective and whose methods you’re comfortable with. Online tools can help (see sidebar below). But some of the best information may come from a charitable group’s own website, Palmer and others say. And if that site lacks useful information, including about results, that can be a red flag.

Pro tip: Think about results holistically, rather than accepting metrics of “impact” at face value. For example, the number of shoes given to children doesn’t necessarily equate to lives transformed or a community improved.

Michael Matheson Miller, who helped create a documentary on the global antipoverty industry, urges some reframing of mind-sets about charity. “We tend to treat poor people like objects – objects of our pity ... of our charity ... of our compassion. And I think this comes from a good heart. We see a problem, and we want to help,” Mr. Miller says. While supporting disaster relief is important, the deeper need, he says, is to see people as “the protagonists of their own story of development.”

Traditionally, “getting out of poverty has to do with giving people access to institutions of justice and enabling them to create prosperity in their families, communities, and their economies,” says Miller, who works at the Acton Institute in Grand Rapids, Mich.

Q: What’s the best way to help financially after a natural disaster?

Here are some general guidelines from experts: Give money, not supplies. Give to reputable organizations experienced in this work. (Such groups may be national or local; the Charity Navigator website often lists organizations that are responding to a specific event such as hurricane Harvey.) And spread gifts out over time. Recovery from a disaster can take years, yet most donations come in the first few weeks, when the event is in public thought.

Q: How can people avoid being scammed?

“Donor beware” is a good motto, and it’s generally best to avoid donating money on the fly. Do some research on groups before giving. Also, be wary of unsolicited phone calls or emails from unfamiliar charities. Ditto if people say donations need to be in cash, by gift card, or by wiring money.

When one does give, rather than sharing a credit-card number over the phone or clicking a link in a possibly fraudulent email, use a browser to type in the charity’s website address and make a donation there. Or mail a check.

Q: Are there ways to give even when money is tight?

Of course! One way is to volunteer for a group. Or raise awareness about a cause by sharing on social media. And one’s own paid work or consumer activity can be done with an eye toward having a positive effect on the world.

Also, technology can turn action into money. One example is the smartphone app “Charity Miles.” It tracks one’s exercise like running, walking, or biking, and for each mile, participating companies will donate to a charity of one’s choice. Another example is “Donate a Photo,” run by Johnson & Johnson, which lets a user give a dollar to charity for each photo he or she posts through the app.

Remember that even a modest amount of money makes a difference to the recipient organization. Sometimes one’s employer will match the gift, thus multiplying it, notes Palmer of The Chronicle of Philanthropy.

Joining a “giving circle” is a way for people to pool resources and have a bigger effect than they could separately. Not only may such efforts help specific charities, but they may also promote a wider culture of giving. And that’s an important issue, since the share of Americans donating to charity has fallen in recent years, says Benjamin Soskis of the Urban Institute in Washington.

Q: Is charity becoming more democratized, thanks to the internet or other forces?

Yes and no, says Mr. Soskis. As the preceding question and answer note, the avenues for giving are growing. “A lot of people are thinking now more creatively about how to expand the notion of who gets to count as a philanthropist,” and many charitable groups are learning to listen to a wider array of voices, he says. “One of the major themes of philanthropy in the last decade has been the inadequacy of the technocratic approach, and the need to at least combine it with a more grass-roots oriented, participatory approach as well.”

The amount of information available to average donors online is also rising.

At the same time, the trend in recent years is that a higher percentage of charitable donations is flowing from a wealthy few, the opposite of democratization. One result, say experts including Palmer at the Chronicle of Philanthropy, is that some institutions such as universities are doing well at attracting money, while less-elite nonprofits such as those in social services may be struggling.

Empowering more people is an important goal, Soskis says, in charitable giving just as in other arenas of society like voting or employment. “Having a wide base of people engaging in society, expressing themselves, expressing their preferences, makes for a healthier society,” he says.

Other resources to consult

The first three groups listed here can be good starting places for general information on the finances and transparency of individual charities:

Charity Navigator (charitynavigator.org)

GuideStar (guidestar.org)

CharityWatch (charitywatch.org)

UniversalGiving (universalgiving.org): The organization offers a vetting system for nonprofits and projects, as described in founder Pamela Hawley’s latest column for the Monitor, in the Nov. 12 issue, page 40.

BBB Wise Giving Alliance (Give.org): This offers a wealth of information on specific charities, plus general pointers.

GreatNonprofits (greatnonprofits.org): It’s like a Yelp for charities, though not as chock-full of useful reviews yet. It has the ability to filter for comments from clients, donors, etc.

GiveWell (givewell.org): This group does in-depth vetting of selected charities, weighing their effectiveness. The result is an annual list of a few dozen recommended charities. Users can also read about GiveWell’s “effective altruism” philosophy, which, while not for everyone, is thought-provoking.

Websites of specific charities: After looking at overview websites like the ones listed here, don’t forget the added step of reading how a nonprofit describes its own activities.

Growfund (mygrowfund.org): This is an easy way (no minimum donation) to start a “donor-advised fund,” in which one can manage tax-deductible giving over time.

Consumer Reports

(consumerreports.org/charities/best-charities-for-your-donations): The venerable consumer guide offers assessments of some top charities in an online report.

Perception Gaps (CSMonitor.com/perceptiongaps): The Monitor’s podcast includes an episode on giving (Part 7 in the series). Have a listen to this and the other episodes!

Giving USA

Perception Gaps

Who’s giving, and how?

Staying with our altruism theme, the latest episode of our Perception Gaps podcast looks at the nature of generosity and how it transforms the givers, as well as the receivers.

Monetary donations to US charities have been rising in recent years, but volunteer rates are slowly declining. Currently, about 1 in 4 Americans gives time to a civic organization. The top four activities: helping with food collection or distribution, fundraising, general help (including giving rides), and tutoring, according to the organization NonProfits Source. In our latest Perception Gaps podcast, we look at assumptions about who’s giving and why. Are liberals more generous than conservatives? As a group, baby boomers tend to give more time than Millennials or Gen Xers. And military veterans tend to be the most generous with their time. The National Conference on Citizenship 2016 report shows that veterans are more likely than non-veterans to vote, volunteer, give to charity, work with neighbors to fix community problems, and attend public meetings. And generosity is the pathway to happiness. Across many nations, “what we find is that the spending on yourself doesn't seem to correlate with your happiness, but the percent of your income that you spend on others is a strong predictor of how happy you are with your life in general,” says Harvard School of Business Prof. Michael Norton, coauthor of the book “Happy Money: The New Science of Smarter Spending.”

Giving USA

Books

Louise Penny’s unlikely motto for murder: ‘Goodness exists.’

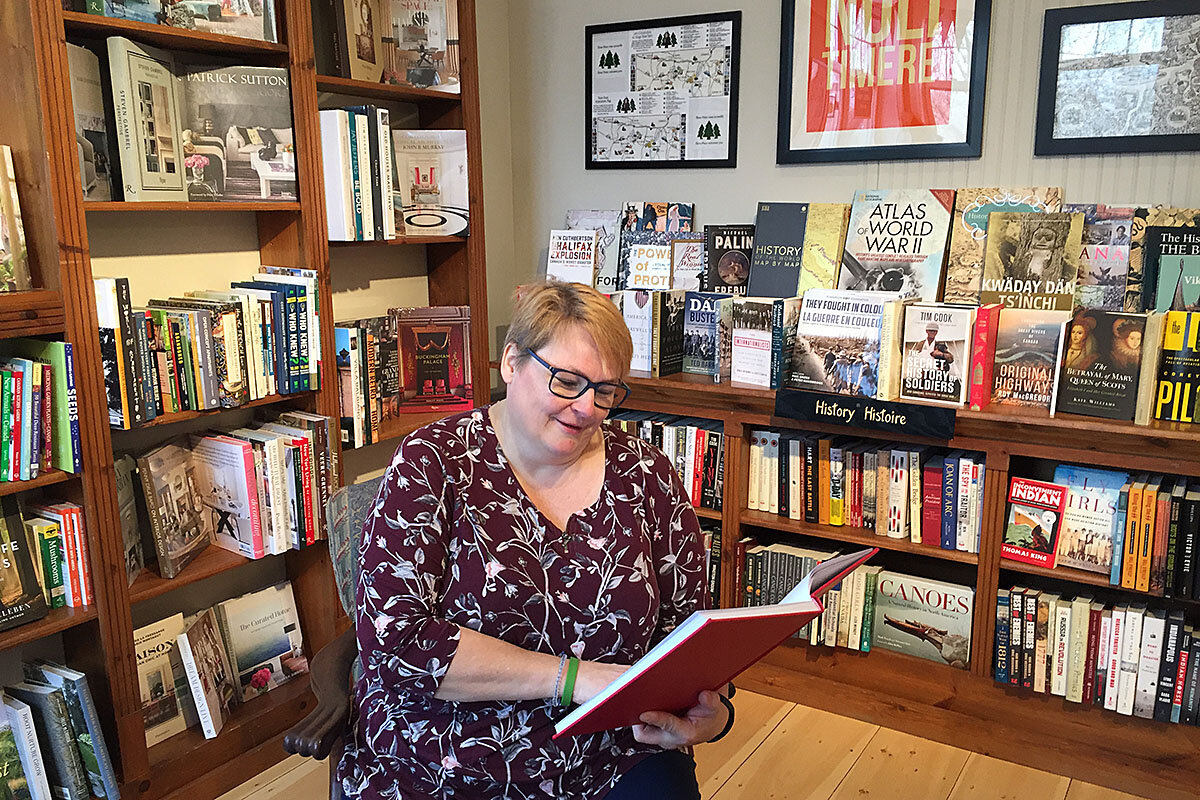

Let’s put our biases on the table: Louise Penny has a bunch of fans at the Monitor. Compassion, community, and great characters filled her first novel, “Still Life,” which was featured in our newsroom book club last month. Our reporter found this Canadian murder mystery writer no less inspiring in person.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

It would be easy enough to turn up in Louise Penny’s home of Knowlton, Quebec, with its bookstore, bakery, and corner bistro, and feel that Chief Inspector Armand Gamache might pass you on the street. Ms. Penny’s 14th book – in 14 years – goes on sale Nov. 27. “People often ask me, ‘Does Three Pines exist?’ I have to tell them it doesn’t,” says Penny. For her, the town has always been an allegory. It’s where she lives when she chooses to be kind, she explains. “Kingdom of the Blind” revolves around an elderly woman and her will – and of course a murder. But like all of Penny's books, the whodunit is secondary to the subjects of goodness and decency, the things taken for granted, and the blind spots in life. Much of the author's inspiration has come from the poet W.H. Auden. After a battle with alcoholism; a hard, two-decade career in journalism; and a bout of self-loathing that not only made her dislike the cynical side of herself, but herself altogether, she read these words: “Goodness existed: that was the new knowledge. His terror had to blow itself quite out/ To let him see it.”

Louise Penny’s unlikely motto for murder: ‘Goodness exists.’

Fans of bestselling author Louise Penny make pilgrimages across the Eastern Townships of Quebec in search of Three Pines, the rural village where her elaborate mystery novels are woven.

It would be easy enough to turn up in Ms. Penny’s real-life town of Knowlton, with its bookstore, its bakery, and corner bistro, and feel that Chief Inspector Armand Gamache and the townspeople in her crime series might jump off the pages and pass you on the street.

“People often ask me, ‘Does Three Pines exist?’ I have to tell them it doesn’t,” says Penny. For her, in fact, the town has always been an allegory, ever since the first book was published in 2005. And even though she admits it can sound “woo woo,” she calls Three Pines not a place, but a state of mind. It’s where she lives when she chooses to be kind, she explains.

From the moment she opens her front door, with a warm smile and her giant, 14-year-old golden retriever Bishop panting at her side, I know I’ve arrived at Three Pines.

Penny’s 14th book – in 14 years – goes on sale Nov. 27. “Kingdom of the Blind” revolves around an elderly woman and her will – and of course a murder that Gamache needs to solve. But like all of her books, the whodunit is secondary to the subjects of goodness and decency, the things taken for granted, and the blind spots in life.

These themes have always pushed her books beyond the mystery genre, earning her readers who are ultimately drawn as much to Gamache’s masterful detective work as to Penny herself – her outlook and the fearlessness and generosity of spirit reflected in her characters.

Inside Brome Lake Books in Knowlton, owner Lucy Hoblyn has set up a Louise Penny corner, where she says people from all over the world descend, increasingly each year. “Every book I read I see Louise in it, her humor, her passion. Three Pines is for her, her place, the place where she came and re-started her life.”

Much of Penny’s inspiration has come from the poet W.H. Auden. It was his poem to Herman Melville that touched her, before she started the series. This was after a battle with alcoholism; a hard, two-decade career in journalism; and a bout of self-loathing that not only made her dislike the cynical side of herself, but herself altogether, she says.

And she read these words: “Goodness existed: that was the new knowledge. His terror had to blow itself quite out/ To let him see it.”

She had just turned the corner. “I was close enough that I could still feel the vestiges of the terror. But I was also feeling that incredible awakening of hope. Of how beautiful the world is and how beautiful people are.”

She met her late husband, Michael Whitehead, who coaxed her to quit her job and fulfill a lifelong dream of writing a novel. And that’s how Three Pines started to take shape. Her copy of Auden still sits next to her laptop, on the wooden table where she writes each morning – a minimum of 1,000 words a day. It is literally falling apart.

A safe place, despite the murders

Three Pines is not just a place to find goodness, but it is safe – perhaps ironic since it’s the setting of more than a dozen murders. And yet a sense of community, and living a good life, always prevails in Three Pines. That’s how Ms. Hoblyn says Penny lives within her real community. (On the day of our interview, she is trying to fob one of the wreaths she made for a fundraiser for a local shelter on her assistant, Lise. Penny rose at 3:30 a.m. to first get in her daily writing.)

“That sense of community, the yearning that we all feel, I think that one of the reasons the books are successful across borders and across cultural groups and ethnic groups and language groups is because as humans we have certain things in common and one of the things is I think we really want to belong,” says Penny, who has won multiple awards for the series, including five Agatha Awards. “I get so many emails from people about the bistro and about wanting to sit in the bistro with that group of friends where people are accepted.”

Her main character was inspired by her late husband, who was the director of hematology at Montreal Children’s Hospital, what Penny calls “the worst job in the world, including homicide detective.” And yet he chose to live with joy, like Gamache, because he understood the privilege to make the choice.

When she set out to create her central figure, she recalled reading that Agatha Christie grew weary of her main character, Hercule Poirot. She remembers thinking: “If the books are published and I live with him for the rest of my life, do I really want a main character who I find really annoying?”

She took many walks, and it occurred to her: “Just to create a character I would marry, give him all the qualities I admire, not just in a man but in a human being,” she says. “And not a perfect man, because that would be very annoying, but someone who struggles to be decent.”

Penny lost her husband, who was diagnosed with dementia, in September 2016 after 20 years of marriage. She had planned to take more time off than she did, when she found herself next to the fireplace, Bishop at her side. A thought sprang to her mind from dealing with her husband’s will. “We were talking about executors, and someone said in passing, ‘Did you know that anyone can be an executor?’ And I thought, ‘Now there’s an interesting idea.’ ”

She returned to her wooden table with a feeling she hadn’t had in a long time. “The terror had blown itself quite out,” she says, returning to Auden. “And I could feel light again, levity. I was still sad but that anticipatory grief was gone, the dread. So I could just write with joy.”

Her new book has already been received with rave reviews, but getting to this place was not seamless. As a radio journalist, she says her every word was prescribed to the second. She was full of anticipation when she gave up those confines. “I thought, ‘oh great, now my free spirit can come out.’ It turns out I have no free spirit. It’s very caged and likes it that way.”

Penny suffered writer’s block for five years, under the pressure of writing “the best book ever written, that was the plan, the top of the list.” One day she looked at her bedside, years after her husband stopped asking her how “the book” was going. She saw among the pile the golden age crime novels she’d been devouring since she was 8.

She also credits a group of women artists she met in the countryside after she moved from Montreal, who called themselves “Les Girls,” for giving her a window onto the creative process. Their influence is reflected in the strong female characters that play defining roles throughout her series. “I got to see some triumphs, but I also got to see some big, stinking flops. Really what I got to see was that no matter what happened, they got out of bed. It didn’t kill them.”

‘Nobody would [read] a crime novel set in Canada’

When I mention Penny to friends and family in the US, many say they read her avidly or know someone who does. In Toronto, she is unknown among all the new friends I have met. Indeed, she made The New York Times bestseller list before any Canadian one.

“When I was trying to sell the books early on and everybody said ‘no,’ one of the comments I got from a lot of Canadian publishers was that nobody would be interested in a crime novel set in Canada,” she says. “Some had invited me to set them somewhere else. Mostly the States. And to be honest I was so desperate to be published, I considered setting it somewhere in Vermont. I remember thinking: How different can it be? It’s just 20 miles across the border.”

Today she thinks the fact they are set in Canada – with generous nods to Canadian artists, history, and Quebecois identity – is among their greatest selling points. “It’s very humbling to realize how many of my beliefs I'm willing to compromise,” she says, laughing.

She says she would not recognize the person she once was, “thankfully.” “What I mean is the outlook on the world, the sense that people can’t change. And that's one of the themes in the books too. People do change, for the worse, but they change for the better too.”

As I’m sitting with her, feeling as though I could go on doing so all day, I think that what really draws readers to Penny’s books is neither its Canadian history nor its intricate resolutions but the chance to hunker down for several hours with Penny herself. Here’s a person who overcame self-loathing, who published her first book at age 46, who still carries around that universal self-doubt and shares it generously, always with a sense humor, as well as the occasional expletive. Yet she always comes back to her driving message: “Goodness exists.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

To keep youth from gambling, ask those who abstain

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Britain’s Gambling Commission has issued a new survey of the problem of youth gambling. Yes, more youths ages 11 to 16 are placing bets. And yes, more are “problem” or “at risk” gamblers. But the study also takes a different, and perhaps more helpful tack. It asked the vast majority of children who do not gamble for their reasons and influences in making such a choice. More than half said they simply are not interested in waging bets or considered themselves too young. Nearly two-thirds said their parents would prefer they not gamble. Nearly 60 percent agreed that “gambling is dangerous.” And depending on their background, 5 to 16 percent cited religious reasons not to play games that rely on a belief in luck or that can ruin lives. The lesson for countries trying to curb youth gambling is to tap into the persuasive moral reasoning of such children. While they still deserve protection from inducements to gamble, they are often wise beyond their years, showing the moral strength to choose a life based on talent and teamwork, not an illusive notion of luck.

To keep youth from gambling, ask those who abstain

Like many countries lately worried about young people being drawn to gambling, Britain has just issued an in-depth survey of the problem. Yes, more youths ages 11 to 16 are placing bets on gaming activities. And yes, more are “problem” or “at risk” gamblers. But the study by the Gambling Commission also takes a different, and perhaps more helpful tack.

It asked the vast majority of children who do not gamble for the reasons and influences in making such a choice.

More than half said they simply are not interested in waging bets or they consider themselves too young under the law. Nearly two-thirds said their parents would prefer they not gamble. About a quarter recognize they would lose money.

Just over 40 percent said gambling might lead to future problems. Nearly 60 percent agreed that “gambling is dangerous.” And depending on their background, 5 to 16 percent cited religious reasons not to play games that rely on a belief in luck or that can ruin lives.

The lesson here for countries trying to curb youth gambling is to tap into the moral reasoning of such children. It may be as persuasive as all the bans and restrictions on gambling. (In China, technology giant Tencent plans to use facial recognition of online gamers to spot minors, relying on a police database of the Chinese population.)

In Britain, more children have placed a bet than have consumed alcohol, smoked, or taken drugs, according to the survey. One reason for this problem is the rise of online gambling-style social games, such as Candy Crush, that often provide nonmonetary rewards. Such supposedly harmless gaming can help kids develop a taste for gambling with real money.

Another reason is ubiquitous marketing of Britain’s national lottery, sports gambling, and other popular games of chance. More than half of England’s top football (soccer) clubs, for example, have gambling company logos on their shirts. And since 2014, total spending by gambling companies on marketing has increased 56 percent. Yet, as the survey found, 85 percent of young people said they were not ever prompted to gamble based on an advertisement or sponsorship.

Children who feel free of the urge to gamble are a resource in any campaign against gambling. While they still deserve protection from inducements to gamble, they are often wise beyond their years. Out of the mouth of babes comes moral strength to choose a life based on talent, teamwork, and hard work, not an illusive notion of luck.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Cheerful’ giving

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Liz Butterfield Wallingford

No matter what the state of one’s finances may be, cultivating a selfless, giving heart is natural for all of God’s children.

‘Cheerful’ giving

Black Friday 2018 is in the books. So are Small Business Saturday and Cyber Monday. And today – for those who still have money to spend after this trifecta of shopping days, as someone recently quipped – we come to Giving Tuesday, a global movement encouraging charitable giving.

It’s a noble concept. A generous spirit is well worth nurturing every day. There’s a Bible passage that expresses this beautifully: “Every man according as he purposeth in his heart, so let him give; not grudgingly, or of necessity: for God loveth a cheerful giver” (II Corinthians 9:7).

I’ve always loved this idea, partly because it’s so inclusive – for “every” one, all of mankind, or humanity – and especially because it places such value on the spirit with which we give. In fact, there’s no emphasis at all on the quantity or monetary value of what’s being given. Rather, it points to the idea that no matter what the circumstances – our financial situation, how much spare time we have, where in the world we’re located – we can all cherish a giving spirit.

Some years ago, a desire to make a financial contribution to an organization that I felt was meaningful and important became stressful. I had felt genuinely inspired to give in this way, but now I worried about giving “too little” in the eyes of whoever would process the donation and about disadvantaging myself by giving “too much,” if I were to give more.

After a couple of days with lots of fretting (and no giving), it occurred to me that at that point, no matter what I gave, I certainly wasn’t being a “cheerful giver”!

I thought of another Bible verse that relates to giving: “Freely ye have received, freely give” (Matthew 10:8). This statement by Christ Jesus strikes me as a command as well as a promise. Jesus’ teachings and healing works reveal that God is good and that His love fills all space, embracing all creation, because God is limitless Love itself. Each of us receives the innumerable spiritual blessings that God, good, loads us with (see Psalms 68:19) – such as love, harmony, abundance, joy.

So that’s the promise for all of us, for right now and forever. As Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science and founder of the Monitor, writes, “To those leaning on the sustaining infinite, to-day is big with blessings” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. vii).

And Jesus’ command is to give, to express love outwardly to one another. It’s actually natural for one to do this – and to enjoy doing so! Since love’s source, God, is infinite, we always have enough love to express. It’s simply how we’re made, as the reflection of inexhaustible Love. Science and Health explains, “Giving does not impoverish us in the service of our Maker, neither does withholding enrich us” (p. 79).

As I mentally paused to think about all this, I saw that my self-involved approach was inconsistent with my true identity. Each of us is the spiritual expression of God’s love and goodness, which blesses all and inspires in us the desire to bless others in turn and to give.

The burden I’d been feeling lifted, and shortly thereafter I felt inspired to donate a particular amount, which ended up being just right. Most important, though, what I learned in this experience has helped me give – love, joy, kindness – more freely and cheerfully.

No matter what the state of one’s finances may be, cultivating a selfless, giving heart is natural, because we reflect God, the Giver of boundless good to all. And opportunities abound for each of us to give joyfully, meaningfully, and appropriately – today and every day.

Adapted from a Christian Science Perspective article published Sept. 24, 2015.

A message of love

A wall of sand

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about Europe’s fresh look at returning art taken from colonial outposts.