- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

For children and their parents, a bedtime story

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp

Every Tuesday evening, Belinda George climbs into a pair of pajamas and reads a bedtime story to her kids.

All of her kids.

The principal of Homer Drive Elementary in Beaumont, Texas, reads on Facebook live so that every child at her elementary school can have the experience of someone who cares about them reading to them and wishing them good night.

In addition to “Tuck-in Tuesdays,” she also hosts dance parties and will show up at a child’s home if the child needs help. (As word has spread beyond the school district, children from out of state have started tuning in to watch Ms. George, wearing, say, a giant pair of red-and-black wings, read “Ladybug Girl.”)

“If a child feels loved they will try [in school],” Ms. George told The Washington Post. “There’s no science about it.”

Parents also need someone to show them the way, and for Jessica Ullian, that person was Brookline, Massachusetts, children’s librarian Paula Sharaga.

“Paula taught me to be a mother. Not how to nurse or change diapers, but how to play and sing and make noises that seemed like nonsense to me, but were an endless delight to my child,” Jessica Ullian writes in a tribute on WBUR of the joy she and her daughter found in the Coolidge Corner Library basement with Ms. Sharaga and her puppet, Mrs. Perky Bird.

After hearing about Ms. Sharaga’s death, Ms. Ullian wondered: “Who will teach everyone else how to parent now that she’s gone?”

So, in honor of Ms. George and Ms. Sharaga, grab a book, snuggle up with a little one, and make your silliest sound.

Now for our five stories of the day.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

What Huawei court battle really means

The lawsuit filed yesterday by Chinese tech giant Huawei sets up a look at two US values seemingly at odds: the ideal of open competition and the ideal of putting national security first.

-

Clarence Leong Staff

Nations around the world are eyeing the arrival of so-called 5G networks as a new epoch for wireless networks – integrating devices with advancing online services including the “internet of things,” where all manner of personal, corporate, and government equipment is web-connected. But who should be trusted to build it? That’s the crux of a high-stakes legal battle between China and the U.S.

On Thursday, a leading Chinese tech firm, Huawei, accused the U.S. of unfairly shutting it out of American markets based on unproven fears. Its lawsuit follows a U.S. effort to prosecute one of Huawei’s top executives on charges including intellectual-property theft.

The emerging fight reflects a clash of values that may seem ironic. The company from Communist-led China is appealing for its right to compete in global markets, while the world’s leading free-market economy is putting up barriers. But experts contend some balancing of open markets and national security is inevitable. Says Scott Harold, an expert on Asia, “[It] makes sense for any country to always be ... making sure that if something is a critical piece of your infrastructure, that it be secure.”

What Huawei court battle really means

When it comes to the next generation of telecommunications – which could make cars truly self-driving, boost mobile phone downloads a hundredfold, and bring real-time “touch” to virtual reality – who are you going to trust to build it?

Companies in the West or in China?

That’s the high-stakes battle now emerging from dueling legal actions involving Huawei, one of China’s leading tech companies. On Thursday, Huawei formally accused the U.S. government of unfairly shutting it out of American markets based on unproven fears. The company’s lawsuit follows a U.S. effort to prosecute one of Huawei’s top executives on charges including evading sanctions on Iran.

The emerging fight over Huawei’s role reflects a clash of values that, on the surface, may seem ironic. The company from Communist-led China is appealing for its right to compete in global markets, while the world’s leading free-market economy is putting up barriers.

Underneath the surface, analysts say the story is more complicated.

Nations around the world are eyeing the arrival of so-called fifth-generation or “5G” networks as a new epoch for mobile networks. It promises the integration of wireless devices with advancing online services including the “internet of things,” where all manner of personal, corporate, and government equipment is web-connected.

“[It] makes sense for any country to always be ... making sure that if something is a critical piece of your infrastructure, that it be secure,” says Scott Harold, an expert on Asia and defense policies at the Rand Corp., a think tank near Washington.

And for his part, he sees limits on Chinese companies, including Huawei, as a valid step that goes hand in hand with America’s free-market principles.

No westward drift for Beijing

For years in the 1990s and early 2000s, U.S. policymakers held to the hope that over time China’s government would draw closer to global norms on things like human rights and property rights. Signs in recent years have led many to conclude that, for now, those hopes are unfounded.

“The passage of time is actually going to make things worse, in this view, because China is perfecting its technology-enabled authoritarianism, it’s getting more repressive at home and more aggressive internationally,” Mr. Harold says.

Even though Chinese companies are viewed by many Western companies as reliable suppliers, they are caught up in such doubts. Huawei has won rising market share worldwide for its networking equipment, but along the way it has also stirred doubts for alleged connections with theft of intellectual property, and concerns that its own products fall short on security.

The Iran-related allegations against the company have landed the firm’s chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, in house arrest in Canada as the U.S. seeks her extradition for trial.

Hauwei says it is being pilloried without evidence.

In filing its new lawsuit Wednesday, the company argued that the U.S. Congress served unconstitutionally as “judge, jury, and executioner” by approving a defense bill that bans federal agencies and their contractors from buying its equipment.

Hauwei said its equipment contains no hidden “backdoors” to be exploited, and has denied that it is beholden to China’s government. Ren Zhengfei, the founder of Huawei and a former engineer in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, told the BBC last month that “We would rather shut Huawei down than do anything that would damage the interests of our customers.”

Outside analysts doubt it has that autonomy. William Carter, a security expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, says “China has made it clear in their national security law that basically any Chinese company can be drafted into the broader state power apparatus.”

He says that argues for heightened wariness when it comes to procurement of core infrastructure.

The more things change...

The problem is not new – and not confined to China.

Reports of tracking by the U.S. National Security Agency caused an international uproar in 2013 when it was revealed the NSA had tapped phones of world leaders, including of allies, like German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff.

The revelations by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden also showed the NSA was collecting internet data with the help of U.S. companies, including AT&T, Verizon, Microsoft, Facebook, Apple, and Yahoo. Seth Schoen, senior staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, writes in an email, “Many governments have sabotaged and tampered with technology products as a way of spying on foreigners.”

Such revelations hurt technology businesses. In 2014, Cisco had to cut staff because of customers’ fears that the NSA was using back doors in its networking equipment to scoop up online data. That reportedly spurred some businesses to look at alternative equipment suppliers outside the U.S., including Huawei.

Now, “there’s a weird sort of parallel where some people in China may assume that Cisco gear is compromised (or potentially compromised) by the U.S. government, while some people here assume the reverse about Huawei gear,” says Mr. Schoen. “This also gives customers in the great majority of countries no good option if they don’t want to be vulnerable to either risk.”

However the lawsuits shake out, the trust issue with Huawei – and Chinese tech companies – is unlikely to go away. Huawei has established itself as a juggernaut in the industry by owning more “standard-essential” 5G patents than any other company as of early February. Chinese companies in total own 36 percent of those patents, according to IPlytics. In contrast, U.S. companies hold just 14 percent.

A lasting architecture

“You’re talking about the lines and the servers and the various capabilities that will support [data traffic], and that infrastructure is going to be around for a long time,” says Mr. Harold at Rand. “And the United States government ... has deemed that to be critical backbone infrastructure for the economy of the 21st century.”

For now, major U.S. cellphone companies like Verizon have been avoiding Huawei equipment in their networks, as have those in some other nations. But Nick Read, head of British-based Vodafone, has questioned the idea of a ban on Huawei, saying such a limitation – in a market dominated by just a few large providers – could stall the rollout of 5G by more than a year. Other key equipment providers include the Finnish company Nokia and Sweden’s Ericsson.

U.S. companies have been able to dominate in the apps and services that ride atop current 4G networks, and “that’s the bigger market,” says Brent Skorup, a telecom expert at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center. But without Chinese suppliers, U.S. carriers “are essentially left with two or three equipment manufacturers instead of four or five.” That would likely mean higher costs for the networks, he says, although, “it might be worth it for the security.”

Staff writer Laurent Belsie contributed to this story from Boston.

Briefing

The Mueller report is coming. Here’s what to expect.

Although the special counsel’s probe into alleged Trump-Russia collusion is reportedly wrapping up, that doesn’t mean the public will learn everything. Nor will it signal the end of investigations into the president.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Special counsel Robert Mueller is reportedly close to wrapping up his investigation. Appointed in May 2017, Mr. Mueller has been looking into whether members of the Trump campaign conspired with Russian agents to interfere in the 2016 election, as well as whether President Donald Trump engaged in obstruction of justice by firing then-FBI Director James Comey, publicly denouncing the investigation, and dangling potential pardons.

No direct evidence of a Trump-Russia conspiracy has emerged to date, although it remains unclear what Mr. Mueller and his team may have uncovered.

Since Justice Department guidelines suggest that a sitting president may not be indicted, whatever conclusions Mr. Mueller reaches will likely be delivered in a written report to the newly-confirmed attorney general, William Barr. It will then be up to Mr. Barr to determine how next to proceed and how much of the report to share with Congress and the public.

If the report contains substantial evidence of wrongdoing, it could become the basis of an impeachment proceeding in the House of Representatives.

The Mueller report is coming. Here’s what to expect.

Special counsel Robert Mueller is reportedly close to wrapping up his investigation. Appointed in May 2017, Mr. Mueller has been looking into whether members of the Trump campaign conspired with Russian agents to interfere in the 2016 election, as well as whether President Donald Trump engaged in obstruction of justice by firing then-FBI Director James Comey, publicly denouncing the investigation, and dangling potential pardons.

No direct evidence of a Trump-Russia conspiracy has emerged to date, although it remains unclear what Mr. Mueller and his team may have uncovered.

Since Justice Department guidelines suggest that a sitting president may not be indicted, whatever conclusions Mr. Mueller reaches will likely be delivered in a written report to the newly-confirmed attorney general, William Barr. It will then be up to Mr. Barr to determine how next to proceed and how much of the report to share with Congress and the public.

If the report contains substantial evidence of wrongdoing, it could become the basis of an impeachment proceeding in the House of Representatives.

Will the report be made public?

Mr. Barr said during his confirmation hearing that he would make as much of the report public as possible, “consistent with the regulations.” Under Justice Department regulations, prosecutors are prohibited from releasing evidence gathered in a grand jury investigation. Mr. Barr may also decide not to release parts of the report in order to protect sensitive national security information.

The Justice Department typically does not announce that it has decided against prosecuting someone – in other words, prosecutors don’t reveal evidence of wrongdoing and then explain why that evidence did not warrant the filing of charges.

An exception to that practice took place in July 2016, when Mr. Comey announced that charges would not be filed against Hillary Clinton over her use of a private email server while serving as secretary of state.

Trump opponents, many of them Democrats, are pushing for Mr. Trump’s case to be handled the way Mrs. Clinton’s was. They want Mr. Mueller to outline in full detail any evidence of wrongdoing by the president and his associates, regardless of whether prosecutors believe it would justify criminal charges or impeachment.

Ironically, some of the president’s strongest supporters – including his son, Don Jr. – are also calling for broad disclosure of everything related to the Mueller investigation, including which Trump associates were placed under surveillance and what evidence, if any, was used to justify that action under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

The decision about what to make public rests first with the attorney general. If information is turned over to Congress, it will then be up to Congress to decide whether to pursue impeachment or additional investigation. Evidence in an impeachment proceeding would eventually become public.

What might the Mueller report say about collusion?

The first priority of the Mueller team was to identify whether Russia and members of the Trump campaign conspired to interfere in the 2016 presidential election. Mr. Mueller has indicted 12 members of Russian military intelligence for their alleged involvement in the hacking and public release of embarrassing emails from the Democratic Party and Clinton campaign officials. The indictment mentions various Americans, but it does not identify any American – let alone a Trump associate – as a co-conspirator. Of course, there is nothing to prevent Mr. Mueller from issuing a superseding indictment to include newly identified members of a broader conspiracy, including Trump associates.

The big remaining question is whether Trump campaign officials – or Mr. Trump himself – helped the Russians in any way in their theft or with the public distribution of the emails. That would amount to a criminal conspiracy between agents of a hostile foreign power and a U.S. presidential candidate to undermine American democracy.

The special counsel’s conspiracy investigation appears to have centered in particular on three individuals: former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort, former Trump lawyer and “fixer” Michael Cohen, and Republican political operative and Trump friend Roger Stone.

Each was targeted by Mr. Mueller’s office for early morning raids involving more than a dozen federal agents who seized massive volumes of paper and electronic records.

Roger Stone

Investigators want to know whether Mr. Stone helped coordinate the release of the stolen emails to maximize their political damage to the Clinton campaign. To date, prosecutors have presented no evidence of such coordination. Instead, Mr. Stone was indicted on charges that he obstructed a congressional investigation by making false statements to the House Intelligence Committee and by trying to convince another witness to refuse to testify.

It is well known that Mr. Stone was trying during the 2016 election season to discover as much information as he could about the hacked emails. But the extent of his contacts with WikiLeaks and the Russians is unknown – at least so far.

It is not illegal to reach out to Russian agents or WikiLeaks to try to discover damaging information about a political opponent. But it is illegal to lie to Congress about any documents or text messages that might expose those efforts.

Paul Manafort

In many ways, Mr. Manafort was the most obvious suspect for alleged Russian collusion, having worked for years as a consultant to pro-Russian political figures in Ukraine. A key member of his staff had links with Russian intelligence, according to a U.S. intelligence assessment. At one point during the 2016 campaign, Mr. Manafort is reported to have shared confidential polling data with this associate.

The full significance of that sharing, if accurate, is not yet known. If, for example, the data was turned over to Russian agents and was used to target particular groups in the U.S. or for other strategic political purposes to damage the Clinton campaign, that action would likely constitute a criminal conspiracy to interfere in the 2016 election.

Mr. Manafort also had a potential motive for helping the Russians, in that he owed a Russian oligarch, Oleg Deripaska, a substantial amount of money.

The problem with these theories is that they are only theories. Mr. Manafort has been convicted of tax evasion and bank fraud, and pled guilty to witness tampering and failing to register in the U.S. as a lobbyist for Ukraine. But he has not been charged with engaging in a conspiracy to fix an American election – at least not yet.

Mr. Manafort is set to be sentenced Thursday and next week, in two different jurisdictions. The 69-year-old political consultant could spend the rest of his life in prison. Under these circumstances, he has a strong incentive to cooperate with prosecutors. But some believe Mr. Trump is considering issuing a presidential pardon, which might encourage Mr. Manafort to be less than completely forthright with investigators.

Michael Cohen

In his controversial and still largely unconfirmed “dossier,” former British intelligence officer Christopher Steele wrote that Russian sources told him that Trump’s lawyer, Michael Cohen, played a key role in a covert Trump campaign-Kremlin conspiracy to undercut the Clinton campaign.

One entry, dated Oct. 19, 2016, said: “According to [a] Kremlin insider, Cohen now was heavily engaged in a cover up and damage limitation operation in the attempt to prevent the full details of Trump’s relationship with Russia being exposed.”

A second dossier entry, dated Oct. 20, 2016, said that Mr. Cohen met in August 2016 with Kremlin officials in Prague, in the Czech Republic.

A third, dated Dec. 13, 2016, said that Mr. Cohen went to Prague with three associates during the last week of August or the first week of September. “According to [Steele’s source], the agenda comprised questions on how deniable cash payments were to be made to hackers who had worked in Europe under Kremlin direction against the Clinton campaign and various contingencies for covering up these operations and Moscow’s secret liaison with the Trump team more generally.”

The dossier said the hacker-operatives were paid “by both Trump’s team and the Kremlin.”

Asked in a public hearing on Feb. 27 before the House Oversight Committee whether he had traveled to Prague in 2016 for any secret cover-up meetings with the Russians, Mr. Cohen denied it. He added that he did not meet with any Russians anywhere in Europe in 2016.

“Questions have been raised about whether I know of direct evidence that Mr. Trump or his campaign colluded with Russia. I do not,” Mr. Cohen said in his House testimony.

He added: “But, I have my suspicions.”

Mr. Cohen did testify about hearing Don Jr. tell his father, “the meeting is all set” – a comment he believes referred to the June 2016 Trump Tower meeting between top members of the Trump campaign and a Russian lawyer, in which campaign officials were told they would receive “dirt” on Mrs. Clinton. According to Mr. Cohen, Mr. Trump replied: “OK good.... Let me know.”

No charges have been filed related to the Trump Tower meeting, but it has been a source of media focus because it could suggest a possible conspiracy to receive and publicize emails allegedly stolen by Russian agents.

One of the lingering mysteries of the campaign is why Mr. Trump seemed to go out of his way to paint Russian leader Vladimir Putin in a positive light.

Some Trump critics have suggested it was because the Kremlin held compromising and embarrassing material against Mr. Trump. Former acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe said that he and others suspected in the spring of 2017 that the newly elected president may even have been acting as a Russian agent.

But Mr. Cohen’s testimony points to a different explanation as to why Mr. Trump was reluctant to criticize Mr. Putin during the presidential campaign in 2016.

Mr. Cohen said Mr. Trump never expected to win the election, and instead viewed the campaign as an opportunity to highlight the Trump brand. And he may have been currying favor with Mr. Putin to try to win approval for a proposed Trump Tower project in Moscow.

“He never expected to win the primary. He never expected to win the general election,” Mr. Cohen told Congress. “The campaign – for him – was always a marketing opportunity.”

That might explain why Mr. Cohen continued negotiating a Moscow tower deal at least through June 2016. Mr. Cohen pled guilty to lying to Congress in 2017 when he claimed, falsely, that the Moscow project negotiations ended in January 2016.

Mr. Cohen said Mr. Trump kept the ongoing negotiations secret “because he stood to make hundreds of millions of dollars on the Moscow real estate project.”

If there is no evidence of a conspiracy to fix the election, was the collusion narrative a ‘hoax’?

Devin Nunes, the ranking Republican on the House Intelligence Committee, says he believes members of the Clinton campaign worked with sympathetic Obama administration officials at the FBI, Justice Department, and CIA to use unproven allegations in the Steele dossier to open a counterintelligence investigation into members of the Trump campaign.

“This was the Democratic Campaign Committee working with the Clinton campaign that produced this dirt and fed it into the FBI to start this investigation in the first place.” Mr. Nunes said in a Fox News interview on Sunday. “No collusion, no collusion conspiracy, no obstruction.”

But not everyone on Capitol Hill has abandoned talk of a Trump-Russia conspiracy.

Adam Schiff, the Democratic chairman of the House Intelligence Committee said in a recent interview on CBS’s Face the Nation that he believes there is “direct evidence of collusion,” notwithstanding Mr. Cohen’s recent public testimony.

He says the evidence includes emails, through an intermediary, from Russians offering “dirt” on Mrs. Clinton. “They offer that dirt. There is an acceptance of that offer in writing from the president’s son, Don Jr., and there are overt acts in furtherance of that,” Mr. Schiff said. Those “overt acts” include the June 2016 meeting at Trump Tower and the various lies to cover up that meeting.

Mr. Manafort’s sharing campaign polling data with his associate in Ukraine is also strong circumstantial evidence of collusion, according to Mr. Schiff. And Mr. Cohen’s testimony about overhearing a phone conversation between Mr. Stone and Mr. Trump about WikiLeaks’ plans to release stolen emails is further evidence, he said.

Still, “while there is abundant evidence of collusion, the issue from a criminal point of view is whether there is proof beyond a reasonable doubt of a criminal conspiracy,” Mr. Schiff said. “And that is something that we will have to await Bob Mueller’s report and the underlying evidence to determine.”

If Mueller report finds no conspiracy, will that exonerate the president?

Not necessarily. Mr. Mueller and his team have also been investigating whether Mr. Trump engaged in obstruction of justice when he fired Mr. Comey in 2017. The special counsel has examined whether Mr. Trump exerted improper influence when he reportedly asked Mr. Comey if he might consider dropping an investigation into National Security Advisor Michael Flynn’s contacts with the Russian ambassador. And there are questions about whether Mr. Trump sought to obstruct the investigation when he publicly raised the possibility of presidential pardons at a time when Mr. Mueller was trying to exert pressure on individuals to cooperate with prosecutors.

What other investigations might the president face?

Mr. Trump may celebrate the release of the Mueller report, particularly if it finds no collusion between his campaign and Russia. But the end of the two-year probe will have little, if any, effect on an array of other investigations, hearings, and lawsuits that will dog Mr. Trump and his associates at least through the 2020 presidential election.

Democrats in Congress are beginning to pivot away from a sharp focus on Russian collusion to embrace a broader range of allegations about Mr. Trump, his family, his associates, and his business. The new focus appears to be on alleged abuses of power.

This effort gained momentum with Mr. Cohen’s recent testimony. While Mr. Cohen expressed doubt about whether Mr. Trump conspired with the Russians to interfere in the 2016 election, he nonetheless suggested several other areas of potential wrongdoing by the president and his associates. Chief among them is whether Mr. Trump conspired with Mr. Cohen to violate federal campaign finance laws, a matter being investigated by prosecutors in the Southern District of New York.

Mr. Cohen pleaded guilty last year to making an illegal campaign contribution to Mr. Trump when he arranged for a $130,000 hush-money payment to former adult film actress Stormy Daniels to prevent her from going public with allegations that she and Mr. Trump had engaged in an extramarital affair. The payment took place in the final days of the 2016 presidential campaign.

In his testimony before Congress, Mr. Cohen said he was directed by Mr. Trump to make the payment, and that Mr. Trump promised to reimburse him. He presented a copy of a signed personal check that he said Mr. Trump gave him as partial repayment.

At issue is whether Mr. Trump’s involvement in the hush-money payments is a violation of campaign finance laws, and whether that violation would warrant impeachment.

If the payment was campaign-related, it should have been publicly disclosed under the campaign finance reporting system. But if it was primarily a private matter – in which Mr. Trump was attempting to prevent his family from learning of his alleged affair – and was paid for with Mr. Trump’s own money, there would be no requirement for disclosure.

Apart from criminal investigations, various Democrat-controlled committees in Congress are expected to begin aggressive oversight hearings dealing with controversial aspects of the Trump presidency.

Jerrold Nadler, the Democratic chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, has reached out to 81 Trump associates seeking documents and information that might shed light on a wide range of suspected questionable activities by the Trump Organization, the Trump campaign, and the Trump administration.

Representative Nadler is seeking documents or information revealing any financial transactions with the Russian government or any Russian individual; any gifts or emoluments from a foreign government; any information about the proposed Trump Tower Moscow project; any details about the June 2016 Trump Tower meeting; information on changes made to the Republican platform concerning U.S. support for the Ukrainian armed forces facing off against Russian troops; any attempt to share 2016 election or polling information with foreign individuals; any discussions involving U.S. sanctions against Russia; any contacts with WikiLeaks; and the content of private meetings between Mr. Trump and Mr. Putin in 2017 and 2018.

The House Oversight Committee also heard from Mr. Cohen that Mr. Trump inflated the value of his assets to boost his net worth on paper, but understated the value of his assets to help reduce his tax liability. A number of committee members questioned Mr. Cohen closely about which members of the Trump Organization might be able to address such issues. It appears a goal of many members of the committee will be to obtain a copy of Mr. Trump’s tax returns, which he has so far refused to release.

For Gaza youths who faced Israeli fire, a lifelong sacrifice

This one is a tough read. Young Gazans badly wounded at protests are confronting the costs of their action, even as Israeli and international rights groups speak out against the use of live fire.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

For the past 11 months, protests on the Gaza-Israel border, at times violent, have become a routine flashpoint in the decades-old Palestinian-Israeli conflict. According to the United Nations, 263 Palestinians have been killed by live Israeli fire as participants in the so-called March of Return as they have approached the border fence.

But thousands have also been wounded, Gaza health officials say. Mohammed Musbaih, age 17, is one of many teenage boys and young men celebrated as heroes of the Palestinian struggle after being disabled by their wounds. The youths say they were motivated to protest how difficult the Israeli blockade of the Gaza Strip has made daily life for them. They voice bitterness that their efforts to capture the world's attention have ended up with no real change, only the crutches, wheelchairs, and depression that has followed.

“My message to the international community is to put an end to these protests and fulfill our demands,” Mohammed says. “People here are losing their souls and parts of their bodies due to the fire opened toward them at the borders. My message to Israeli soldiers is to stop targeting us.”

For Gaza youths who faced Israeli fire, a lifelong sacrifice

One night recently, Jehad Abdulaziz Musbaih could not find his teenage son, Mohammed.

Mr. Musbaih, a resident of Khan Yunis in the southern Gaza Strip, finally found him at the local cemetery where the 17-year-old’s right leg had been buried.

It was amputated after Mohammed was shot and wounded by an Israeli sniper at a demonstration on Gaza’s border. For the past 11 months, the border protests, at times violent, have become a routine, weekly flashpoint in the decades-old Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

The youth was weeping as he sat near the spot of his leg’s “grave.”

“It tore up my heart watching my son cry,” says Mr. Musbaih, a former civil servant. He says his son has been trying to hide his anguish from the family. But he found him that night at the cemetery, as he has so many nights at home, crying alone in the darkness where he thinks no one will hear him.

Mohammed Musbaih is one of more than 6,500 Gazans – many of them, like him, teenage boys and young men – who have been wounded in the demonstrations by live fire, according to Gaza health officials.

Many of them have been hit in the legs by Israeli fire when crowds of hundreds, even thousands, of protesters swell near the border fence with Israel, protesting against Israel’s blockade of the strip.

To youths of Mohammed’s generation who have grown up amid persistent violence, participation in the protests is a national act of heroism, experts say, and the idea of being wounded is seen as a path to self-respect.

U.N. report

Every Friday, chaotic scenes play out. Some demonstrate peacefully, but others burn tires that paint the sky with thick black plumes of smoke. The Israeli army says the smoke is intended to obscure the vision of soldiers guarding the heavily fortified fence area and to give cover to protesters trying to breach it.

Some use slingshots to hurl stones toward the soldiers and send flaming kites and balloons toward the Israeli side of the border, setting fields and the landscape on fire.

International outrage has been focused mostly on the fatalities – 263 Palestinians have been killed by live fire, according to the United Nations. But Gaza health officials say that among the thousands of wounded, some 500 are now permanently disabled, including more than 100 who have had legs amputated.

Last Thursday, the United Nations Human Rights Council accused Israeli soldiers of intentionally opening fire on those protesting, even when they did not pose any “imminent threat.” The report said some demonstrators were acting violently, but that the situation on the Gazan side did not constitute combat conditions that justify the level of Israeli fire. The report also accused Israeli snipers of shooting at individuals clearly recognizable as journalists, health workers, children, and people with disabilities.

Israel rejected the report, calling it hostile and slanted, and blamed Hamas, the Islamic militant group that controls Gaza, for carrying out what it said were terror activities during the demonstrations.

Living with the consequences

Far from the international stage of accusations and counteraccusations, young men on crutches are now a common sight on the streets of Gaza.

When first wounded they are celebrated as heroes of the Palestinian struggle. But less visible is the painful aftermath: the surgeries and rehabilitation in a medical system perpetually on the brink of collapse, operating amid power outages and a shortage of supplies and physicians; the care given by parents at home at a time the young men are supposed to be making their own way in the world and contributing to the family income; and the anguish these young people feel as they realize they will be spending a lifetime living with the consequences of the Friday afternoon they went out to demonstrate.

“In the past, I never used crutches. I used to run with my legs,” says Mohammed Abu Hasanian, 13, from the Jabalia refugee camp in the northern Gaza Strip. He says he was watching soldiers on a hill on the other side of the fence from a distance of about 100 meters when he was shot in his leg, which was later amputated.

Mohammed Musbaih is a high school senior with thick wavy hair that he styles with gel. Clutching the sides of his metal crutches, he walks the packed-sand streets of his neighborhood that he once raced down, kicking soccer balls and chasing his friends.

He recalls the day last April he and his cousin went to the demonstrations after lunch. He describes arriving at a peaceful scene and spotting an older woman holding a Palestinian flag. He asked to take the flag and then approached the fence, placing it to fly there.

The next thing he remembers he was writhing on the ground, shot in the leg by a sniper’s bullet. By that time, he says, Israeli gunfire was ongoing, and it took about 30 minutes for a break in the fire to come and for Palestinian medics to reach him. With no ambulance available, he was initially transported by motorcycle.

“I dreamed of being a soccer player and an engineer. But when I became disabled, my dreams were also amputated,” he says.

A path forward

There are some efforts underway to help find a path forward for these amputees, many of whom are fixated on their disability thwarting even nonathletic pursuits. To compensate for the overwhelmed health system, there are international aid groups that sent physicians and medical supplies to help provide extra medical attention. And there is a volunteer group of Turkish doctors, for example, that works to deliver psychological support as well. Among the medical teams that have entered Gaza to help are Arab citizens of Israel who are part of Physicians for Human Rights-Israel.

And there is a new Gaza soccer team comprised of amputees that was founded by a member of the Palestinian Paralympic Committee. It’s called the Team of Champions.

Mohammed Musbaih says he is excited to join. Most of the players lost a leg after protesting at the fence demonstrations. They play each other on special sports crutches that are provided through local donations, and they get coaching in how to use them to race down the field.

The players say it has given them a feeling of hope to be active and involved again. Coaches say they see how being out on the field and together in a group as teammates has helped boost their spirits.

March of Return

It’s been almost a year since the border protests were launched. Originally, they were planned by civil-society activists as a peaceful set of demonstrations seeking to draw international attention to conditions inside impoverished Gaza, with its ongoing power outages, fuel shortages, and 70 percent unemployment that they charge is the direct result of Israel’s ongoing blockade.

The protests were called the March of Return, because the demonstrators are also demanding the right for those whose families became refugees during the war that led to Israel’s creation in 1948 to return within Israel’s borders. The majority of Gaza’s 1.9 million people are descended from refugees.

Piggybacking on popular support for the protests, leaders of Hamas quickly took over their organization, at times exhorting the marchers to breach the border fence.

Palestinian human-rights groups say Israeli soldiers shoot anyone who touches the fence or comes close to it. The Israeli army says it has continually called on Gazans not to approach what they refer to as “the combat zone,” the area near the fence, and not to take part in the protests in the first place.

Aside from the United Nations report, Israeli and international human-rights organizations have been speaking out against the use of live fire, describing it as a violation of international law and immoral, and alleging that most of those killed were unarmed and therefore not a danger.

In response to The Christian Science Monitor’s query about the number of dead and wounded, the army said it uses live ammunition “as a last resort and in accordance with open-fire regulations that comply with international law.”

The army, it said, “operates against violent riots and terrorist activities … which include shooting at soldiers, attempts to penetrate into Israel, attempts to damage the security infrastructure, burning tires, throwing stones, throwing Molotov cocktails and grenades in order to harm IDF [Israeli Defense Forces] soldiers.”

The army statement also describes Hamas as a “terrorist organization” that “uses its civilians as human shields and places them at the forefront of terror activity, demonstrating cynicism and contempt for human life.”

“A badge of honor”

Fadel Abu Hain, a psychiatrist in Gaza, says young Palestinians in the Gaza Strip grow up living close to danger. Between 2009 and 2014 there were three wars between Hamas and Israel in a 149-square-mile sliver of land that has one of the highest population densities in the world and no safe havens. In between, violent flare-ups are almost routine.

“The concept of danger is different for youth in our community,” he says. “They believe that getting close to danger that exposes their lives to death is an act of nationalism and a badge of honor.

“Those who go to borders and get injured and then lose their limbs think they have participated in a heroic act,” Dr. Abu Hain continues. “They think this is how people would respect them. They feel positive for their act, forgetting the danger they put themselves in.

“But after the injury,” he says, “mainly after they see their legs have been amputated, they start thinking of the hard situation they put themselves in.”

The youths say they were motivated to march to protest how difficult the Israeli blockade has made daily life for them. They voice bitterness that their efforts to capture the world’s attention have ended up with no real change, only the crutches, wheelchairs, and depression that has followed.

“My message to the international community is to put an end to these protests and fulfill our demands,” Mohammed Musbaih says. “People here are losing their souls and parts of their bodies due to the fire opened toward them at the borders. My message to Israeli soldiers is to stop targeting us.”

A doctor recalls

Mohammed Abu Mughaiseeb, a physician who works with Doctors Without Borders, remembers last May 14, the day Palestinians mourn Israel’s creation in 1948, as an especially “black day.”

At a hospital where he was stationed, more than 250 wounded with gunshot injuries arrived within three hours.

“Patients were everywhere, so they waited for treatment in the hallways and in the parking area and some waited in lines outside of the surgical rooms where medical teams worked 48 hours straight,” he says.

Many of those with leg wounds will need multiple surgeries over the years and ongoing physical therapy and rehabilitation, all services that are in short supply.

Abdullah Qassem, 16, from Gaza City, is now in a wheelchair, both of his legs amputated. He looks back with these words:

“This has been the dark turning point of my life. All aspects of my life are changed, whether it’s going up and down stairs, getting to school or the bathroom, or even leaving the house. I used to play soccer, go to sea, play with my neighbors.

“But the amputations stole whole parts of my life away.”

Saud Abu Ramadan contributed reporting from Gaza.

A deeper look

Pray and wash: Finding church in unexpected places

For many, worship has always been about much more than the edifice in which it occurs. Today, a new locus of spiritual growth is emerging around alternative settings that redefine “church.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

-

By G. Jeffrey MacDonald Correspondent

“The laundromat is my church.” Those are the words of an Episcopal Church deacon. She’s not being flip. Neither are those who describe ritual and reflection in a state park – or over a Tuesday night potluck – as church. The lack of traditional packaging is by design. The idea: Having people gather in an informal setting instead of just under a steeple embodies the Gospel in a way that’s comfortable, especially at a time when many Americans remain leery of organized religion.

Hundreds of such faith gatherings are springing up. Is it a fringe movement, or a glimpse of tomorrow? A lot of the momentum does come from mainline denominations seeking growth. About 20 percent of new United Methodist churches are nontraditional. Traditional churches offer advantages, such as institutional longevity, but alternative churches have advantages too. They are, for example, less costly to establish and maintain.

This much seems clear: For a social subset that includes the unchurched and the disaffected, a redefined church meets a need. “They’re looking for … more contemplation, for silence, reflection, and thought,” says Steve Blackmer, pastor of Church of the Woods in Canterbury, New Hampshire. “I discovered… That’s who this can serve.”

Pray and wash: Finding church in unexpected places

When Julie Butcher goes to church, she looks forward to giving thanks to God, lending a supportive hand, breaking bread with friends – and helping people wash a tub of clothes.

“The laundromat is my church,” says Ms. Butcher, an Episcopal Church deacon, as children play and washers churn at Suds Up here in this city one hour west of Boston. “There’s no judgment. People come here and they’re welcomed and loved. It doesn’t matter what they look like or what their life is like.”

Butcher’s church happens here inside a noisy, family-owned laundromat that transforms once a month into something more akin to the kingdom of God. When it does, blessed are those overwhelmed by heaps of smelly socks and soiled T-shirts. Anyone who doesn’t have access to laundry facilities at home gets an opportunity to wash, dry, and fold them here free of charge.

Funded by area churches and other organizations, the monthly gathering is called Laundry Love. It has no formal worship service nor preplanned Bible talk. In fact, any visible signs of church are subtle enough to miss, except for the four women in clergy collars who on this day are keeping things running smoothly by shepherding kids and watching jeans tumble in front-load washers.

The lack of church packaging is by design. The idea is that having people gather around a practical project in an informal setting embodies the Gospel in a way that’s comfortable, especially at a time when secularism is on the rise and many Americans remain leery of organized religion.

“Whether they recognize it or not, they are growing in [their] relationship with God,” says Meredyth Ward, the Episcopal priest who started Worcester’s Laundry Love and is called “pastora” by her informal flock. “When they offer prayers themselves, they are claiming an identity in Christ. It doesn’t look like normal church. Some of them may never walk into a normal church. But church happens. God shows up.”

Laundry Love attests to a trend that’s putting a new face on the religious establishment in the United States. More and more, gathering for church no longer means coming together for Sunday morning worship with hymns and preaching under a steeple. In mainline Protestant denominations, which trace roots in America to the Colonial period and are vying to reverse five decades of decline, church is increasingly centered around other days of the week, sharing different kinds of experiences, and meeting in community settings. Hundreds of these faith gatherings are springing up across the country in places more rustic than reverent.

In Littleton, Colo., a Presbyterian clergyman leads “wild church gatherings” as part of his Church of Lost Walls. He guides people of all spiritual backgrounds through three hours of ritual and reflection in Roxborough State Park.

Near Grantsburg, Wis., Lutherans make church extra casual with Soup in the Coop – a light meal before 6 p.m. Wednesday worship in, yes, a chicken coop. In Los Angeles, Episcopalians and Lutherans encourage family farming alongside faith at the Abundant Table, a community-supported agriculture venture with an optional Sunday night church component. Other worshipers are gathering over dinner or in the outdoors where kids climb trees and romp with the family dog during services.

Underneath it all looms a fundamental question: Is this just a fringe movement, or is it what the mainstream churches of tomorrow will look like?

A lot of the momentum for the movement is, in fact, coming from mainline denominations as they try to find ways to start new churches.

For the United Methodist Church, nontraditional strategies didn’t exist as recently as a decade ago, according to executive director of community engagement and church planting Bener Agtarap. Today about 20 percent of new churches are nontraditional – people gathering in places such as homes and on horseback trails.

Of the 432 congregations started by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America since 2013, more than two-thirds are nontraditional, according to director for new congregational development Ruben Duran. Among the new venues: Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, a major rail hub.

The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) is committed to launching 1,001 new worshiping communities between 2012 and 2022. Forty-two percent of these new churches so far are meeting in unconventional places.

As the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) works to start “1000 new churches in 1000 different ways,” nontraditional will be increasingly common in years ahead, according to Terrell McTyer, minister of new church strategies. “Eventually the idea of doing things nontraditionally will become the tradition,” says Mr. McTyer.

To be sure, churches have always convened in secular places. Early Christians worshiped in homes, and recent generations have followed suit by gathering in pastors’ living rooms or school auditoriums – at least until they could afford their own space for Sunday services. What’s different now is how many new churches often have no designs on going traditional no matter how established they become.

The movement is being driven by several factors. Denominations need to reverse or at least slow the decline in membership, and new churches tend to grow faster than long-established ones.

Nontraditional churches are also cheaper to set up. The venues are usually either donated or rented for only a few hours a week. The United Methodist Church aims to plant one church per day, in part to help reverse numerical decline, Mr. Agtarap says. But establishing a traditional church even in a dedicated rental space costs at least $500,000 for the first three years. “We don’t have that kind of money,” he says.

Yet numbers are hardly the only thing propelling the movement. Scholars agree the new ventures are expanding the idea of church by bringing services to people in forms that are more accessible to them.

“The aim is to reach people in new ways that are present where people are, rather than asking people to convert first to a kind of a culture before they’re even able to entertain what Christianity is about,” says Bryan Stone, a professor of evangelism at Boston University School of Theology who is studying the new movement.

Dr. Stone says it’s not uncommon for nontraditional churches to disband after six or seven years, especially if a charismatic leader moves on. But participants in the movement are determined to prove skeptics wrong, or at least to practice authentic Christianity for as long as possible. It’s a mission fraught with challenges but also loaded with possibilities.

“I don’t think [nontraditional churches] are necessarily an answer” to mainline decline, Stone says. “But I do think it’s a big enough wave ... to sit up and say, ‘Look, this reminds us of other sorts of reformations in church history....’ They’re doing church in ways that really need to happen.”

One mile north of Suds Up in downtown Worcester, Methodists are pioneering a new congregation just a thousand feet from a traditional United Methodist church. Here a worship service is the main event, but it’s aimed at those who wouldn’t attend an established church – at least not anymore.

Simple Church Worcester, as it’s called, meets every Tuesday night at the Garden Fresh Courthouse Café, a quick-serve restaurant by day and sacred rental space by night. On a recent cold night, passersby pause to read a sandwich board and ponder the chalked question: “What if CHURCH was a dinner party?”

Inside, 15 participants happily answer the question. They share potluck dinner at one long table positioned by the front window for maximum visibility. At the head of the table in a black clergy shirt, blue jeans, and L.L. Bean boots sits the pastor, LyAnna Johnson, who came to Massachusetts from Texas to start a dinner church.

Ms. Johnson doles out spiritual questions for diners to discuss in groups of three or four. When all have been fed, one worshiper breaks out a guitar. Congregants sing a simple refrain – “breathe in hate/ breathe out love.” Having shared Communion bread before the meal, they now pass around the rest of the Sacrament – a pitcher of “wine” (grape juice) – and hear a hopeful reminder from Johnson. “In every moment,” she assures her flock, “God offers a chance to choose a different way.”

Simple Church Worcester marks an attempt to expand a model launched in the nearby town of Grafton by its pastor, Zachary Kerzee. The formula is simple: Worship over dinner, let Bible-inspired conversation be the sermon, and engage in revenue-producing activities, such as website design for churches or bread baking, to help benefit communities and cover costs associated with the church.

On this night, visitors from another United Methodist congregation in suburban Charlton, Mass., have come downtown to eat and learn how to connect, as Simple Church does every week, with a table mostly filled with 20- and 30-somethings.

“What intrigued me was their ability to reach unchurched people that are not, for whatever reasons, attracted or called or interested in a Sunday morning kind of church,” says Wanda Santos-Perez, pastor of Charlton City United Methodist Church. She says her church wants to adapt the model in Charlton and see if a dinner church format might draw local young adults.

But those gathered at Simple Church aren’t unfamiliar with traditional services. Many had attended established churches in their younger years and left hurt, disillusioned, or both. The nontraditional space at Simple Church, where authority to preach is dispersed around the table, has become a refuge where the alienated find affirmation.

Anna, who asked that her last name be omitted, says her conservative evangelical upbringing had been a big part of her life. She left in part because “politics had sort of infected the evangelical church.” She also felt she couldn’t be her true self there.

“Here I can express my doubts and not be so judged,” Anna says. “We’re all allowed to disagree. We don’t all have to believe the exact same thing.... Often I’ll go away with a new perspective on a Bible story or want to do more research. It really has given my faith a new lease on life.”

Others share similar stories of being turned off by church, but also feeling something was missing when they left.

“I attended another church and it wasn’t working out,” says Ellen Kurtz, who describes herself as shy and therefore more comfortable in a small church environment. Simple Church “is less judgmental. No one here has batted an eyelash if I say I have a chronic illness so I can’t show up some weeks, or I’m not straight. No one has a problem with that. They just want me here.”

Many people showing up at the new churches, in fact, are so-called dones – those who consider themselves done with more established churches. Very few are new to religious services altogether.

Church of the Woods, for instance, is a place where 15 to 20 people gather on average over two Sunday services on a woodsy parcel in Canterbury, N.H. There’s no doubt it’s church, whether attendees are sharing the Sacrament in a field on a brilliant fall morning or chanting Psalms in a small candlelit barn. But it’s also earthy. No matter the weather, attendees venture outside for at least part of the service to reflect on a particular question or topic among the trees, streams, deer, and countless other creatures. Afterward, they listen to each other’s reflections before sharing from the chalice.

Church founder Steve Blackmer, an Episcopal priest, says he felt called by God to establish the church on this site. He aims to reconnect church with nature in a time of environmental crisis. Pastor Blackmer expected the church might draw those who say they find God in a garden or on a mountaintop, not behind stained-glass windows.

Early on, he invited 40 friends, all of whom had spiritual practices of some type and interest in conservation, to take part but to no avail. Those uninterested in organized religion, even if they regard themselves as spiritual, haven’t been drawn to his church, he says.

“They come and they get freaked out,” Blackmer says, sitting in the barn as the sun fades, candles flicker in the windows, and mice rustle audibly nearby. “There’s too much Jesus. The liturgy is too formal. Communion freaks them out. And these are friends of mine. Not a single one of my friends has joined Church of the Woods.”

Instead, Church of the Woods has built a community of about 60 people, most of whom travel substantial distances – in one case, five hours each way – to join like-minded people for a unique worship experience. They don’t all attend weekly or even monthly. They bring a range of church backgrounds: Episcopal, Roman Catholic, Unitarian, and Quaker, among others.

“They’re looking for something with more contemplation, for silence, reflection, and thought, not always this stimulus coming at you,” Blackmer says. Or they’ve left the Catholic Church, he says, after being disillusioned.

When Blackmer rings a cowbell and a Tibetan yak bell, calling his flock back together after 20 minutes of wandering to the sounds of crunching snow and cracking branches, the stories they share reveal another layer of who they are: people finding their way back to the fold after often rocky relationships with established churches.

“There was a latent demand that I didn’t know of,” Blackmer says. “I discovered after the fact: That’s who this can serve.”

Scholars say what’s happening in Worcester and Canterbury is typical of nontraditional churches. The approach resonates with a younger generation in particular that wants to participate in a creative way, not just consume what a religious leader has packaged for their consumption. That’s according to Casper ter Kuile, a ministry innovation fellow at Harvard Divinity School and coauthor of “Something More,” a study of faith groups that claim ancient traditions in new ways.

By rekindling interest among the disaffected, nontraditional churches arguably cater to a growing market. The number of people claiming affiliation with mainline denominations dropped from 18.1 percent to 14.7 percent between 2007 and 2014, according to Pew Research Center. Meanwhile those with no religious affiliation jumped from 16.1 to 22.8 percent over the same period. But only those who once embraced church life and want to try it in a fresh way seem likely to respond.

“Often who it appeals to is people who grew up with church, who have kind of moved away from it or rejected it,” says Mr. Ter Kuile. “It’s not often extremely resonant with people who have never had any experience of church life....”

As nontraditional churches work to become more secure long-term places of worship, they face pressure to avoid turning into something else – a traditional church.

In Dripping Springs, Texas, where ranchland has given way to new homes for commuters to Austin, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America bought a subdivided parcel in 2010 with plans to put up a building and minister to the fast-growing population. But after local Lutherans held Easter services outside on the undeveloped plot, worshipers said they wanted to hold more services there in the sun, shade, and breeze of Texas’ Hill Country.

That led to what’s become New Life Lutheran Church, an outdoor congregation with an average attendance of 70. No building means no office, so the pastor, Carmen Retzlaff, has meetings in coffee shops or on hiking trails. A trailer stores a portable sound system, blankets for cold days when they huddle under a tent, and everything else they might need for a comfortable outdoor experience.

When worship begins, an old horse trough serves as the altar. Attendees bring dogs. Kids are free to climb trees and dig holes during the liturgy. The uniqueness of the experience drew the Coburn family when they were trying to find a church home a few years ago. “It felt like we were killing two birds with one stone,” says Katie Coburn, a New Life parishioner and mother of boys ages 10, 8, and 5. “We could be a part of a faith community and be outside” on Sunday mornings.

New Life is part of the Wild Church Network, a fellowship of about 40 US and Canadian congregations that worship outdoors or will launch as outdoor churches this year. But maintaining New Life’s quirky status requires diplomacy. Some in the church are growing tired of putting up with inhospitable weather and all the weekly work that goes into setting up sound systems and laying out hymnals and other materials that would be ready to go if they had a normal building. They’d like a permanent indoor church, but others insist the alfresco service is essential to who they are as a community.

“There’s been a bit of a push and pull between the people who say ‘we’re just waiting around until we raise enough money to build a building’ and the other people who say ‘we never want a building, what are you talking about?’ ” Ms. Coburn says. A compromise is in the works, she adds: The congregation has a long-term plan to erect an open pavilion to house services and put in a kitchen and bathroom.

Pressures to conform to church conventions have weighed on other congregations as well. New Creation Church in Hendersonville, Tenn., built up momentum with an unusual formula: Worship on a weeknight and spend Sunday mornings on athletic fields, where so many parents and kids gather. By offering cold drinks and face painting as a form of outreach at the sporting events, the Presbyterian-affiliated congregation became a model for how to grow a flock.

But the church shifted once it grew enough to relocate from a home to a storefront site. Churchgoers now meet on Sunday mornings, though the church still does outreach at sporting events at other times and retains a conversational-style worship.

While congregations that remain nontraditional aren’t likely to last more than a few years, says Stone, the Boston University scholar, longevity isn’t the main point. Authentic Christianity is. And denominations are showing they’re not afraid to try.

Take Laundry Love. It’s not an official congregation of the Episcopal Church. Some regulars argue it’s just an outreach, not a church, because it has no choir, no open Bibles, no doctrinal teaching. But others believe this is exactly how churches launch effectively in the 21st century. First comes mission activity to reveal God’s love. The rest comes later.

Either way, people find it’s comfortable –and meaningful. On Valentine’s Day, upbeat music and free pizza create a festive atmosphere for first-time participants, including Tee Hall, who stays at a nearby homeless shelter with her two kids. When Ms. Ward invites anyone interested in prayer to join hands in a circle, Ms. Hall stands off to the side with her kids but absorbs every word.

“It’s a laundromat, so the last thing I would expect is to have a priest here,” Hall says. “But knowing that it’s church people [behind the event] makes people feel good. Who doesn’t want to come to a place that has a lot of church people and even a priest?”

Alternative churches: the future of religion?

Beyond clichés: Teen anxiety prompts closer look at young lives

Seventy percent of U.S. teens say anxiety is the biggest issue they and their friends face. One antidote to the stress creeping in at ever younger ages? Making friends with yourself.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Societal issues like global warming and racism weigh heavily on today’s young people. While getting good grades and fitting in socially still primarily occupy them, they also understand that there is work to be done, and that they will likely be the ones to do it. “It’s stressful to know you’re going to have to be the change,” says eighth-grader Biz Brooks from Acton, Massachusetts.

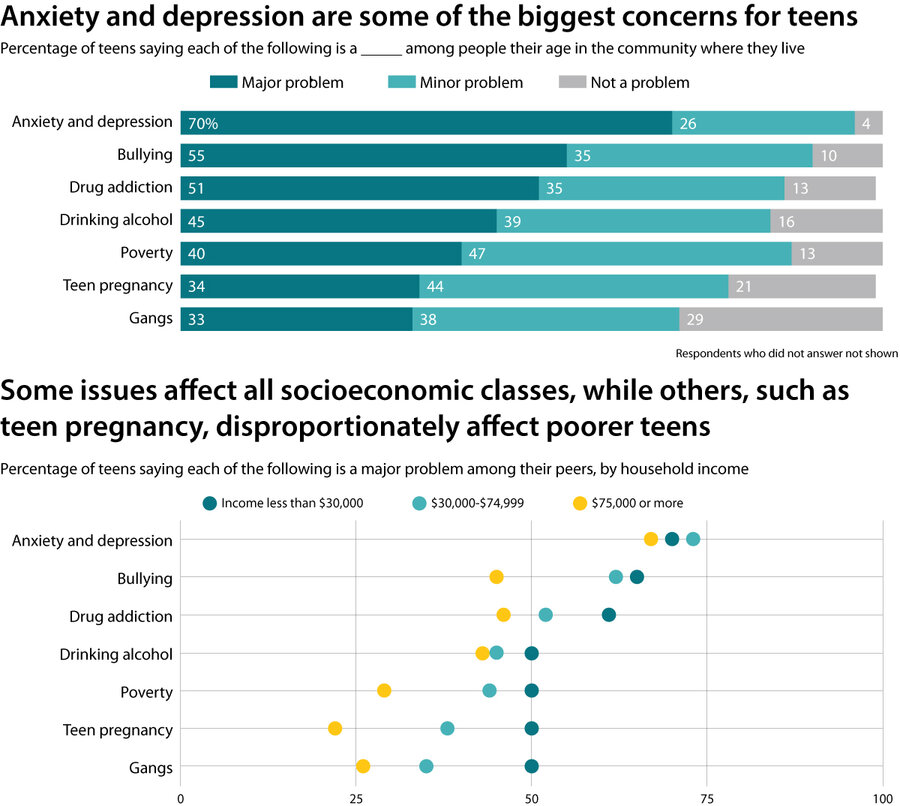

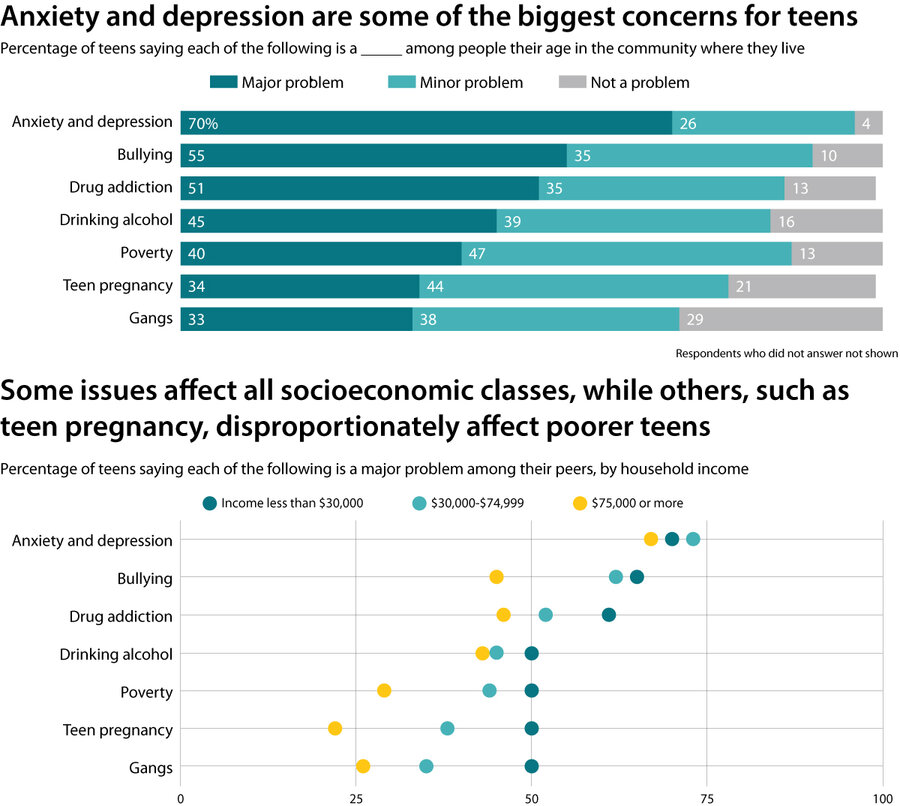

A February report from the Pew Research Center indicates that 70 percent of teens consider anxiety and depression a major problem among their peers. There’s no consensus among researchers about what drives this anxiety, although common theories include fear of failure, the rise of smartphones and social media, changing parenting styles, and a world that feels unusually chaotic.

One solution: focus on self-compassion. “I tend to teach a lot of high achievers,” says Karen Bluth, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “They learn that it’s OK to be kind to yourself. It’s revolutionary for them. I think it’s revolutionary for adults too. It goes against a lot of what our culture teaches us.”

Beyond clichés: Teen anxiety prompts closer look at young lives

Eighth-grade student Biz Brooks and her friends like to chat about K-pop music, photography, and her new dog. But when the teens hang out or send text messages on their phones, they also deal with darker thoughts.

“My friends and I talk about being anxious a lot of the time,” she says. “We talk about how things stress us out because generally we are a pretty stressed group of people.”

Biz lives with her family in Acton, Massachusetts, a prosperous suburb about 30 miles outside Boston.

The 13-year-old may be especially attuned to mental health struggles since her town still reels from a spate of recent youth suicides. Yet new research shows her and her friends’ feelings are far from unique.

A Pew Research Center survey released in February found that 70 percent of teens in the United States consider anxiety and depression a major problem among their peers. That comes on the heels of other studies showing alarming rises in the number of anxiety diagnoses among young Americans and heightened levels of “overwhelming anxiety” in college students. With the issue starting at earlier ages and affecting all races and income brackets, efforts at solutions also appear to be rising.

Anxiety and depression among teens “is significantly worse” now says Karen Bluth, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “I get emails from parents with 11-year-olds who are super anxious.”

There’s no consensus among researchers about what drives teen anxiety, although common theories include fear of failure, the rise of smartphones and social media, changing parenting styles, and a world that feels unusually chaotic.

Biz and her neighbor Charissa Yu, a high school junior, say their anxiety stems from intense pressure to achieve good grades, attend a prestigious four-year university, and hold a successful career that makes a positive impact on the world.

“I want to tell myself that I’d be OK if I failed, but I really don’t think I would be,” says Charissa, who worries about how many advanced classes to take next year. “I definitely feel that anxiety coming up. It’s just a building pressure of ‘how much can I endure?’ ” she says.

Biz calls anxiety “an icky feeling you get that you can’t shake really easily,” and says her friends have been anxious about grades and college since sixth-grade.

‘It’s OK to be kind to yourself’

In the nationwide Pew survey of U.S. teenagers ages 13 to 17 conducted this fall, researchers found 61 percent of teens face pressure to get good grades. The second most common pressures teens report are to look good (29 percent) and to fit in socially (28 percent).

Professor Bluth co-developed a curriculum for teenagers called “Making Friends with Yourself: A Mindful Self-Compassion Program for Teens” that teaches teens how to deal with anxiety by treating themselves kindly, the way they would a friend. She runs trainings on the curriculum around the world.

“I tend to teach a lot of high achievers who have pushed themselves to get where they are and [who are] incredibly stressed and anxious to the point of sometimes being not functional,” Professor Bluth says. “They learn that it’s OK to be kind to yourself. It’s revolutionary for them. I think it’s revolutionary for adults too. It goes against a lot of what our culture teaches us.”

One of the most commonly cited reasons for increased teen anxiety is the rise of smartphones and social media. Psychologist Jean Twenge found dramatic shifts in teen behavior starting in 2012, the first year the majority of Americans owned smartphones.

Biz pushes back against the premise that social media increases anxiety, saying it’s an outlet for self-expression and connecting with others with similar interests. “I run a poetry account [on Instagram] and that makes me really happy all the time.”

For Biz, world issues such as global warming, homophobia, and racism cause more anxiety than social media. “It’s stressful to know you’re going to have to be the change,” if change is going to happen on such issues, she says.

While teens from all demographics face anxiety in themselves or peers, it’s important not to lump everyone together, says Angela Neal-Barnett, a professor at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, and director of the university’s Program for Research on Anxiety Disorders among African-Americans.

“We have to be honest and talk about race and racism, particularly structural racism,” she says. “The research is clear that for black Americans, anxiety is more intense and tends to be more chronic,” especially as black teens experience the recurrence of troubling news reports, such as the shootings of unarmed black men.

Pew Research Center

Tell teens: This isn’t permanent

On a recent chilly evening in Groton, Massachusetts, about 100 people gathered in the local middle school to hear Lynn Lyons, a psychotherapist from Concord, New Hampshire, talk about breaking the cycle of anxiety.

Ms. Lyons cracks jokes on stage as she covers topics ranging from how to prevent and treat anxiety, to how parents can rein in their own anxiety.

In an interview before her talk, Ms. Lyons says it’s key for teenagers to know the feelings they have now aren’t permanent.

“When we use the language of permanence with teenagers, like ‘you have this condition called anxiety’ or ‘you have this disease called depression,’ we are basically saying to them, ‘you will be like this forever,’ ” she says. “That’s the exact opposite message that we want to give teens who are struggling.”

Pew Research Center

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A Muslim call to end words of contempt

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In the Middle East, the word kafir – when used to mean infidel and not merely nonbeliever – can pit neighbor against neighbor, country against country. In Indonesia, the world’s most-populous Muslim country, the rising use of kafir as a religious slur has led to a rise in violence, the ouster of elected officials, and court convictions for blasphemy. Its use by Islamic extremists also threatens to inflame political tensions before national elections in April.

But on March 1, the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia took a stand. The Nahdlatul Ulama issued a statement asking Muslims not to use kafir as a form of “theological violence.” The group offered an alternative word, muwathinun, or citizen, to emphasize that all religious people in Indonesia have equal standing.

The stand is a request, not a command, affirming the view that religious understanding must come from the heart. At the official level, the Indonesian government is trying to end Islamic extremism. The real challenge, as the N.U. statement makes clear, is persuading Indonesians to replace words of contempt with those of mutual affection, as citizens.

A Muslim call to end words of contempt

One way to ignite violence in the Middle East is for one Muslim group to refer to either other Muslims or non-Muslims as kafir. When the word means infidel and not merely a nonbeliever, it is loaded with contempt. It can pit neighbor against neighbor, country against country. And the branding is difficult to counter.

In Indonesia, however, which is the world’s most-populous Muslim country, the meaning of kafir has taken on a stark negative tone only in the past 20 years since the return of democracy to this religiously diverse Southeast Asian nation of 260 million. Its new use as a religious slur has led to a rise in violence, the ouster of elected officials, and numerous court convictions for blasphemy. Its use by Islamic extremists also threatens to inflame political tensions before national elections set for April 17.

On March 1, the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia took a stand against the word as a weapon of discrimination. The 45-million-strong Nahdlatul Ulama (N.U.) issued a statement asking Muslims not to use kafir as a form of “theological violence.”

The group offered an alternative word, muwathinun, or citizen, to emphasize that all religious people in Indonesia have equal standing. “With the nation state model, all community groups have the same rights,” the N.U. stated.

A few other Muslim-majority nations, such as Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, have recently launched efforts to tone down the rhetoric of religious-based contempt. The N.U. has gone a step further by asking Muslims to see all others in Indonesia as sharing a common home, worthy of being treated as equals in order to maintain social harmony.

The N.U.’s stand, of course, is merely a request, not a command, affirming the view that religious understanding must come from the heart. This is the spirit of a new book, “Love Your Enemies,” by prominent American thinker Arthur C. Brooks. The book focuses on how to counter contempt in political discourse.

“Your opportunity when treated with contempt is to change at least one heart – yours,” he writes. “You may not be able to control the actions of others, but you can absolutely control your reaction. You can break the cycle of contempt.”

At the official level, the Indonesian government is trying to end Islamic extremism. In 2017, for example, the Constitutional Court ruled in favor of freedom for all faiths, not just the six religions that are officially recognized (Islam, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism). And the government is also trying to prevent radical ideas from being taught at Islamic boarding schools.

The real challenge, as the N.U. statement makes clear, is persuading Indonesians to replace words of contempt with those of mutual affection, as citizens. In that word, all can be believers.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘I so wanted to be ... popular’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kathryn Jones Dunton

A 2018 Pew survey of U.S. teenagers found that two of the most common pressures teens report facing are to look good and to fit in socially. Today’s contributor shares how a better understanding of her relation to God replaced a yearning to be popular with a desire to express joy and kindness toward others, opening the door to meaningful and lasting friendships.

‘I so wanted to be ... popular’

The pursuit of popularity for its own sake seems rampant in today’s society. For instance, while social media “likes” can be a way to express genuine appreciation, many people see the number they receive as a measure of their worth.

I really understand that yearning for recognition and popularity. When I was in middle school, I so wanted to be one of the popular kids. It didn’t happen, though in high school I found a niche among a group of friends I cherished. However, when I entered college, without any of my old friends, I again felt that familiar desire to be popular, or at least well-liked, above all else.

But my shyness presented quite an obstacle. Part of my shyness, I realized, was related to an overblown concern about what others thought about me. As a child, I had been taught to be very aware of what others thought without regard for what I thought or felt.

In thinking about all this, I was inspired by a sentence that spoke to the idea that it’s something less self-centered, namely our faith, that should be central in our lives. In particular, referring to what was at the heart of the faith I practiced, Christian Science, it says: “He who leaves all for Christ forsakes popularity and gains Christianity.” This is from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science (p. 238), a book I’d been finding increasingly helpful.

I realized I needed to stop focusing on catering to the opinions and judgments of others and instead concentrate on what it means to me to be a Christian. Of course, having friends or being liked isn’t in and of itself a bad thing. But I saw that my motives had been superficial.