- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

At Boston Marathon, everyday heroism and collective hope

There’s plenty afoot out in the big, wide world, but sometimes the world literally races to your door.

The Boston Marathon – which had its 123rd running today – finishes not far from the Monitor’s newsroom. It’s a particularly tough race, and not just because of the city’s capricious April weather.

It’s also a showcase of human connection. A Chicago friend who grew up here and has run it four times recalls the extra support in Wellesley, where students turn out, and on Heartbreak Hill, where the course exacts payback for a long decline.

Gene has marathoned in a half-dozen cities and he comes prepared. But he remembers cresting that half-mile rise at mile 20, staggering, then feeling a steadying arm – a spectator’s – from out of nowhere. Quiet heroes surface often, Gene says, “and they’re total strangers.”

Heroism has deep associations here. Six years after twin bombings killed three people and injured hundreds, testing Boston’s resolve, local poet Daniel Johnson recalls the humbling experience of being asked to compose words to be etched in bronze and mounted on stone at the blast sites, probably by summer.

“The city wanted a universal sentiment,” he says in a phone interview. The task was humbling, he says. It demanded economy of language. Mr. Johnson spoke with the families of those killed and with others. He says he’s been “gobsmacked” by stories of help and healing.

His painstaking work reflects a sense of reclamation. “[The words are] collective,” he says. “Everyone felt that this should be a collective remembrance.” His last verse concludes with a sentiment bigger than heartbreak, bigger than Boston: “Let us climb, now, the road to hope.”

We’re watching the developing story around the fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral (see Viewfinder, bottom) and planning a report from Paris. Now to our five stories for your Monday, including new perspectives on both the U.S. southern border and Ukraine, and a look at how a community circus is changing lives in Ethiopia.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Taxpayers need help. So does the IRS.

Another rite of American spring reminds us that trust and compliance are mutually dependent. A lot hangs on the nation’s tax-collection agency being made – and being seen as – effective and fair.

“When I started at the IRS, we had approximately 35 revenue officers in the Milwaukee area. ... Today we have approximately six,” says Doreen Greenwald, a Wisconsin IRS employee and a workers’ union representative. It’s a sign of how tight budgets have squeezed the Internal Revenue Service over the years, especially since 2010.

It’s not just morale at the tax agency that’s at stake. The result is frustrations for taxpayers trying to resolve issues. Finance experts say it can affect something near the heart of any democratic government: public trust in, and compliance with, the tax system. In the United States, that trust doesn’t appear to be near a breaking point, but experts say it shouldn’t be taken for granted.

At congressional hearings last week, some Republican lawmakers from the party that led IRS budget cuts expressed concerns about improving the agency. “There’s a clear need here for additional enforcement and for additional service,” says Alan Viard, a tax-policy expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute in Washington. “That’s kind of a delicate balance.”

Taxpayers need help. So does the IRS.

Early this month, when Virginia resident Casey Lewis was in a bind over how to pay her tax bill, she tried dialing the Internal Revenue Service. She was hoping to set up a payment plan with the IRS for a significant amount – $1,600 – that she hadn’t expected to owe.

Online efforts with the agency had already failed her. “Your website keeps locking me out because it claims some of my info is wrong (but doesn’t tell me what!),” Ms. Lewis posted on Twitter.

Trying by phone didn’t work any better: After 80 minutes on hold, she felt she had to hang up.

Ms. Lewis is far from alone in having a tough experience while trying to be a responsible taxpayer.

About 4 in 10 phone calls to the IRS go unanswered, staffing and budgets have declined, and the agency patches its databases together with software that dates back as far as the presidency of John F. Kennedy, IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig told members of Congress in hearings last week.

The issue is not just an annoyance. It can mean lost time and money for American taxpayers. And finance experts say it can affect something near the heart of any democratic government: public trust in, and compliance with, the system of collecting revenue for public programs.

In the United States, that trust doesn’t appear to be near a breaking point, but experts say it shouldn’t be taken for granted. Both a tax “compliance gap” and weak public ratings for the IRS signal that, at a minimum, there’s plenty of room for improvement.

“You’ve got to have enough trust so that most people will pay what they owe, most of the time,” says Alan Viard, a tax-policy expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

‘A delicate balance’

Even if citizens may disagree with elements of fiscal policy, that bedrock of trust hinges on people feeling the tax system created by Congress is “fair enough to be legitimate,” Mr. Viard says. It also hinges on the tax-collection agency being perceived as effective: reining in cheating while also being helpful rather than harassing honest taxpayers.

“That’s kind of a delicate balance,” Mr. Viard says. “There’s a clear need here for additional enforcement and for additional service.”

Many other tax-policy experts agree on that general point. Officials and workers at the agency say the same.

“When I started at the IRS, we had approximately 35 revenue officers in the Milwaukee area. ... Today we have approximately six,” says Doreen Greenwald, a 34-year IRS worker who is also a local union president for the National Treasury Employees Union. “And from my perspective, our work has increased based on a lot of the complexities of the tax law, as well as the work itself is more complex.”

This is a year of particularly high stress for the agency and American taxpayers alike.

It’s the first tax-filing season under Republican-passed tax changes signed by President Donald Trump in 2017. While broadly cutting individual and business taxes, the law has also transformed the tax code in ways that many Americans are only now grappling with. And the IRS is still in the process of clarifying the tax law for taxpayers and accountants by preparing detailed guidance on the changes.

Despite that, the positive news is that for millions of Americans the tax-filing process in recent weeks has gone smoothly. The gap between what taxpayers owe and what the IRS receives is large – about $458 billion a year, roughly 12% of owed revenue – yet the U.S. remains a leader on tax compliance compared with many other nations.

“We have the greatest tax system in the entire world,” Ms. Greenwald says. “And it’s based mostly on a voluntary compliance system.”

Signs of strain

Surveys have found that the vast majority of Americans view taxpaying as a civic duty. And by some polls, the IRS has been edging up rather than down in public esteem. Still, signs of strain are clear:

- The IRS ranks near the bottom among federal agencies for its customer service.

- President Trump’s $11.5 billion budget request for the IRS would be a 1.5% increase (with a $362 million boost separately planned for enforcement), but the agency’s budget is down 18% since 2010 after adjusting for inflation.

- A seven-year hiring freeze starting in 2011 strained morale and has left a high share of workers near retirement.

- A six-year plan to overhaul IRS computer systems is underway, but the agency is beset by relentless cyberattacks on the Treasury’s troves of money and taxpayer information.

- Audits of questionable tax returns have plunged even more deeply than the overall cuts in staff.

Some critics say the agency’s woes stem partly from a deliberate attack on its funding by Republican lawmakers, channeling the anti-government spirit of the tea party movement in 2010 and beyond.

But some of the latest Republican rhetoric has been about improving the agency, not abolishing it (as Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, had called for as a presidential candidate in 2016).

Sen. Mike Enzi, R-Wyo., spoke in last week’s congressional hearing about how the closure of a taxpayer-assistance office was affecting his constituents. Commissioner Rettig cited “unexpected recent retirements” for the center’s closure.

Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla., asked about whether the agency needed help in finding cybersecurity professionals (yes, he was told) and about the implications of the tax gap for public trust. Millions of taxpayers “want to get it right, and it really bugs them when someone is ripping the system off,” Senator Lankford said.

Commissioner Rettig agreed, calling for an enforcement presence in “as many neighborhoods as possible.” (And in a separate hearing with House members, he acknowledged the need “to get the audit rates up for the more wealthy taxpayers ... by taking a strong look at the issues that I am aware of that wealthy individuals might engage in,” such as pass-through entities, which allow many firms to lower their tax rates by reporting income on individual returns.)

Assistance deferred

Better customer service is the other side of the coin.

“Its not unusual for me to be on hold for an hour and half or more,” or to not even be offered the option of waiting on hold, says Deborah Bechtel, who says she often calls the IRS in her work as an enrolled agent helping taxpayers near Albany, New York.

When she does get through, she says the workers are doing their best to be helpful, but getting an issue resolved is far from assured.

For Ms. Lewis, the taxpayer from Norfolk, Virginia, the outcome of her efforts wasn’t a happy one. After failing to get through by phone, she ended up selling her late mother’s jewelry to enable payment of her whole remaining tax bill for 2018, she says in a text interview online.

She, for one, would like to see the IRS get more funding.

“I think the IRS could definitely use a bigger slice of the budget,” says Ms. Lewis, who works as an administrative assistant for a health insurance company. “I honestly feel that [the] system is tilted to favor the very rich while setting up roadblocks for the poor and working class.”

She points to the way lobbying by the tax-software industry has – so far at least – put up roadblocks to the idea of a federal “free-file” system that would let all taxpayers largely rely on the IRS to prepare their taxes using information in its databanks (with the opportunity for individuals to amend IRS-prepared forms).

“No one will ever enjoy paying taxes,” Ms. Lewis says. “But making it less onerous for consumers could help.”

Everyone agrees the US needs to fix the border. But how?

Does a shift in thought have any chance against the reality of immigration as a political points-winner for hard-line sides? One source tells our writer that the key might be looking at border security as “an ecosystem,” with variables beyond those that are usually seen.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Immigration is a notoriously divisive political issue, but a recent surge in Central American asylum-seekers crossing the U.S. southern border has reinforced a widespread consensus that America’s immigration system needs an overhaul. A tougher question, though, is whether consensus can be found over what that overhaul should look like, particularly given how inaction has become a fruitful response for the politicians who would need to do the overhauling.

The Trump administration is calling for changes to what they describe as “loopholes” in immigration law, but Victor Manjarrez, a former Border Patrol sector chief, thinks a more structural rethink is required. “We’ve treated border security, really for the last 35 years, as the fence of a static line,” he says. “We should look at border security more of as an ecosystem.”

For Xochitl Rodriguez, an El Paso native who has been helping feed migrants at nonprofit shelters around the city, the current immigration system can work, it just has to be resourced appropriately. If Annunciation House, a local nonprofit, can process 700 migrants a day, she says, “a federal government can figure out how to do this.”

Everyone agrees the US needs to fix the border. But how?

Xochitl Rodriguez crossed the Rio Grande a few weeks ago to visit her aunt’s old studio in Ciudad Juárez. It had been years since she had visited, her aunt having fled to El Paso a decade ago amid intensifying cartel violence.

Born and raised on the United States side of this binational metroplex, Ms. Rodriguez is no stranger to the six bridges that cross the Rio Grande. On her way back, she saw something she had never seen before: hundreds of migrants sleeping behind chain-link fencing under the Paso del Norte Bridge.

“Two hundred people and they were yelling up at us: ‘We’re already four days here in the dirt,’” she recalls. “How as a human do you allow that to happen?”

For months, asylum-seekers – predominantly families and unaccompanied children from Central America – have been arriving at southern border cities like El Paso in numbers not seen in a decade. Community members like Ms. Rodriguez have been working round the clock to help shelter and feed migrants released by overwhelmed immigration agencies.

“El Paso knows how to do it. I wish we didn’t know. I wish we didn’t have to do this,” she says. “From the perspective of this community, it’s especially frustrating to see no help and no real policy change.”

Immigration agencies are working around the clock as well, taking unprecedented steps in response to a migrant surge they say they are ill-equipped, physically and legally, to handle. Two children died in U.S. custody in December, and medical screenings are being conducted for every child under 17. Extra agents are being drafted in from across the southwest border to help process migrants, and wait times at ports of entry now last hours.

While immigration is a notoriously divisive political issue, the current crisis has reinforced a widespread consensus, stretching from federal agencies to immigrant activists, that America’s immigration system needs an overhaul. A tougher question is whether consensus can be found over what that overhaul should look like, particularly given how inaction has become a fruitful response for the politicians who would need to do the overhauling.

The issue with prioritizing changing laws, experts say, is that immigration has become a political wedge issue.

“Wedge issues don’t get resolved. They get used by both sides to mobilize their base,” wrote Sonia Nazario, a veteran immigration journalist, in a New York Times op-ed last October.

Border as an ‘ecosystem’

In addition to legal and policy changes to a system geared toward quickly deporting adult Mexican men, some experts believe a structural rethink is necessary.

“We’ve treated border security, really for the last 35 years, as the fence of a static line,” says Victor Manjarrez, a former Border Patrol sector chief.

“We should look at border security more of as an ecosystem,” he adds, “an ecosystem that is affected by a bunch of variables near and distant, things that border security folks don’t touch but certainly affects them.”

A shake-up in the higher ranks of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) this month hints at how the Trump administration may now seek to plug what it calls “loopholes” in immigration law.

“The only way to fundamentally address these flows is for Congress to act and to reinstate integrity into our immigration system,” said Kevin McAleenan, commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), in a late-March press conference. Commissioner McAleenan is expected to become the agency’s acting secretary after a number of forced resignations last week.

Specifically, there are two areas of the law the Trump administration is seeking to change. A settlement in a 1997 class-action lawsuit called Flores requires the government to hold families for no longer than 20 days. In addition, the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), enacted in 2008, requires the government to put all unaccompanied migrant children into immigration court proceedings unless they’re from Mexico or Canada. The administration is also seeking to raise the standard by which an asylum-seeker can claim “credible fear,” The New York Times reports.

American and international asylum laws, combined with the likelihood of a quick release from detention via the Flores settlement and TVPRA and yearslong backlogs in U.S. immigration courts, form a relatively simple route to life in the U.S. for migrants until at least 2021. A majority of asylum claims are denied – around 60% in fiscal year 2017. That year, 11,022 migrants released from custody were ordered deported after failing to appear for their immigration court hearings, a 21% increase from the year before, according to the Justice Department.

The “border” could be pushed out, says Dr. Manjarrez, now a professor at the University of Texas, El Paso (UTEP), in terms of asylum-seekers being vetted before they arrive at the U.S. border and need to be housed or transported. Could credible fear claims be evaluated in the asylum-seekers’ home country? Could asylum cases be adjudicated in Mexico?

Such proposals would likely be challenged in court. American and international asylum laws are premised on the notion that refugees request asylum once they reach the refuge country because they are in too much danger elsewhere. Last week a federal judge in San Francisco temporarily blocked a DHS policy requiring asylum-seekers to wait in Mexico while their claims made their way through U.S. immigration court in part because it violated laws ensuring migrants “are not returned to unduly dangerous circumstances.”

Also likely to face court challenges is a plan the White House says it is mulling to release detained migrants in so-called sanctuary cities, many of which are Democratic strongholds. On Monday, the chairmen of three House committees asked the White House and agency officials for internal documents on those deliberations, according to The Associated Press.

‘The border story is the blowback’

Instead of tightening asylum requirements, or extending U.S. border control infrastructure into other countries, others believe the current immigration system could work provided it’s resourced appropriately. Just look at Annunciation House, a nonprofit in El Paso that has been sheltering migrants released by immigration agencies, says Ms. Rodriguez.

“If Annunciation House can process 700 people a day ... as an NGO with a minimal budget, a federal government can figure out how to do this,” she adds.

With the CBP budget having increased more than tenfold between 1990 and 2015, the government should be able to detain more asylum-seekers and hire more immigration judges so asylum claims can be adjudicated faster, says Josiah Heyman, director of the Center for Inter-American and Border Studies at UTEP.

“The border story is the blowback from an increasingly dysfunctional and failing immigration court system,” he says.

“The immigration judicial process needs to be quick, efficient, and fair,” he continues, and “everyone needs representation because if they did I think a lot of the inadequate cases would drop by the wayside.”

The CBP is planning to open a new migrant processing center in El Paso in April. Last week U.S. Attorney General William Barr told Congress the Department of Justice is requesting $72 million for 100 new immigration judges, though he also said that “the problem with the asylum laws” needs to be addressed first.

The blame game

The current crisis has been brewing for at least five years, when 2014 saw a surge in unaccompanied minors from Central America at the southern border. The situation has only become more complicated since then, experts say.

CBP announced last week that more than 103,000 migrants were apprehended or found inadmissible at the southern border in March, an increase from 76,500 in February. However, the number of arrested migrants with criminal convictions has been declining. The rise of sophisticated smuggling operations through Mexico and fears that President Donald Trump’s threats to close the border to everyone may actually be realized have supersized migrant flows, meaning those with weaker asylum claims, like economic migrants, are making the journey. But economic migrants can also be indirect victims of violence and government corruption in their countries.

“The dysfunctionality of the U.S. immigration system is something that goes way back,” says Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, a professor at the George Mason University Schar School of Policy and Government. But “it seems like the Democratic Party, and Republicans and the Trump administration, they’re only blaming [each other].”

“This might be the end of an era,” she says, referring to the ousters at DHS. “What we might see now is a real attempt to address the issues that need to be addressed.”

Militaristic and anti-democratic, Ukraine’s far-right bides its time

This one’s about the power of perceptions. Our reporter looks at how more aggressive street tactics by the far-right in one shaky democracy stand to make that group more disruptive than it might otherwise be.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In Ukraine, far-right groups are an extremely controversial topic. And despite considerable stabilization in Ukrainian society in recent years, the danger they pose appears to be growing. Though few in number overall, ultra-nationalists operate with a high degree of impunity, allowing them to openly harass and attack minorities and human rights advocates without repercussions.

In the past year, far-right organizations have carried out over two dozen violent assaults on women’s groups, LGBT activists, and Roma encampments that have left many injured and at least one person dead. It is rare that police intervene, much less bring the attackers to justice. Some worry that such groups, given their anti-democratic ideals, paramilitary discipline, and freedom to operate, could have an outsize influence should Ukraine return to political instability.

“The problem is that these right-wing activists are armed; they have combat experience,” says Ulyana Movchan, director of a nongovernmental organization that provides support to LGBT groups. “They are trying to control the streets and maybe, in future, political life as well. ... They don’t just pose a personal danger to certain activists, they are a threat to the whole society.”

Militaristic and anti-democratic, Ukraine’s far-right bides its time

As people were forming up to stage this year’s March 8 rally for women’s rights in Kiev, a group of about three dozen young men, clad in dark clothes, started harassing the marchers by tearing off their lapel pins and ripping away their placards.

Some of the men tried to pull away a banner from Mariya Dmytriyeva, a well-known spokeswoman for feminist causes. She resisted. “Woman, why are you so nervous?” they jeered at her. Fortunately, she says, police intervened and separated them.

It’s a familiar scene in Ukraine these days, where radical ultra-rightists are an increasingly threatening presence on the streets. “I think that overall these groups are very insignificant in size. But they are very radical and very loud,” Ms. Dmytriyeva says. “If they can get away with attacking us like that, it shows there is something dangerous there.”

Though few in number overall, far-right groups operate with a high degree of impunity in Ukrainian society, allowing them to harass and attack minorities and human rights advocates without repercussions. Some worry that such groups, given their anti-democratic ideals, paramilitary discipline, and freedom to operate, could have an outsize influence should Ukraine return to political instability. Though the ultra-rightists were given much latitude due to their help protecting the Maidan Revolution and the fledgling government that followed, now they highlight a key weakness of the current system.

“During the Maidan there was a context that was comfortable for [the radical right]. During the war [with rebels in the east], it was very comfortable,” says Vyacheslav Likhachev, a historian and expert on Ukraine’s right-wing movements. “Today we do not have a context in which a small minority, with street fighting skills, have the means to create instability. But in case there is instability, they are a very dangerous factor.”

Operating with impunity

Ukraine’s far-right groups, some of which include armed veterans of the war in Donbas, are an extremely controversial topic. And despite considerable stabilization in Ukrainian society over the past five years, the danger they pose appears to be growing.

Just a couple of days after the March 8 rally, scores of far-right activists belonging to the new National Corps party attacked the motorcade of President Petro Poroshenko in the Ukrainian city of Cherkasy, injuring 19 police officers. In the past year, far-right organizations have carried out over two dozen violent assaults on women’s groups, LGBT activists, and Roma encampments that have left many injured and at least one person dead. It is very rare, activists say, that police intervene as they did in Ms. Dmytriyeva’s case, much less bring the attackers to justice.

Analysts say the strength of these groups derives mainly from the weakness of Ukraine’s post-Maidan state, or rather its reluctance to enforce law and order when it comes to the depredations of radical rightists. That may be in part due to the role ultra-right fighters played during the Maidan revolt against former President Viktor Yanukovych, as organized defenders of the protest encampment and sometimes initiators of violence against police.

Even more important is their status as war heroes who formed private battalions and rushed to the front in 2014 to battle separatist rebels at a time when the Ukrainian Army was in serious disarray. As a result they enjoy connections with authorities, and a level of social respectability, that would probably not be the case otherwise.

It’s important to point out that despite their high public visibility and the apparent impunity with which they act on the streets, the far-right groups do not appear to represent any social upsurge of radical nationalism. Indeed, a joint candidate put forward by five of Ukraine’s leading ultra-rightist groups in the March 31 first round of Ukrainian presidential elections, Ruslan Koshulynskyi, won less than 2% of the votes.

Rather, the fear among many here is that if Ukraine’s weak state institutions should again suffer any sort of breakdown, these highly organized, disciplined, armed, violence-prone, and ideologically determined groups might punch far above their weight in determining a political outcome.

‘We are not democrats’

Instability is a prospect that may not be far from the surface in post-Maidan Ukraine. The Right Sector, a militant ultra-nationalist group that played a very prominent role during the Maidan uprising, has since consolidated itself as a political party with an armed wing and a youth movement. It may not be the largest right-wing movement in Ukraine, but it has maintained its revolutionary sense of purpose and complete rejection of the existing order.

“We are not democrats. We participate in elections only because they are a step to revolution,” says Artyom Skoropadskiy, press spokesman of the Right Sector party. “We want to change the whole system. New people, new order, new rules in the state system of Ukraine. We oppose Russia, and we are against Ukraine joining the European Union and NATO. We want Ukraine to be a self-sufficient, independent state.”

The Right Sector backed Mr. Koshulynskyi’s presidential bid simply because it offered an opportunity for political agitation, he says, and the vote tally is of secondary interest.

“Our organization is designed to take power. If circumstances warrant, that could happen by nondemocratic methods. Believe me, we are very capable of acting in extreme situations,” he adds. “At the Maidan we had only 300 activists, and look what we did. In fact, if you consider that there was never more than 1 million people participating in the Maidan altogether, out of a population of 42 million, it shows how things really work. The active minority always leads the passive majority. Scenarios change, and we are ready. Our purpose is to save Ukraine.”

The Right Sector, and other militant street groups such as C-14 and the newly created National Corps, already pose a real and present danger to vulnerable groups of the population, such as gay and transgender people, women’s activists, Roma, as well as any dissidents who might, rightly or wrongly, be viewed as “pro-Russian.”

Ulyana Movchan, director of Insight, a nongovernmental group that provides legal services and other support to LGBT groups, says that people who do not belong to these vulnerable groups of the population should wake up and be more concerned about what is happening.

“The problem is that these right-wing activists are armed; they have combat experience. They are organized into illegal military groups,” she says. “They are trying to control the streets and maybe, in future, political life as well. We do not know what they might do. They don’t just pose a personal danger to certain activists, they are a threat to the whole society.”

Giving too much leeway to nationalists?

Many Ukrainian analysts argue that these new rightist groups are not “nationalist,” but rather racist, intolerant, and extreme social conservatives. But it may be a problem that more mainstream Ukrainian nationalists, such as the Svoboda party – which does not participate in street violence – tend to make heroes of 20th-century “fighters for Ukrainian independence.” Those include Stepan Bandera, whose fascist ideology, collaboration with the Nazis, and participation in wartime ethnic cleansing against Poles and Jews makes him and those like him poor role models for modern Europe-bound Ukraine.

The Ukrainian parliament has passed legislation making it illegal to deny the hero status of Mr. Bandera. In Kiev, a major boulevard was recently renamed “Bandera Prospekt.” It should be no surprise that groups like the Right Sector model themselves on such World War II-era Ukrainian nationalist fighters.

“We are a Ukrainian nationalist group, in the image of Stepan Bandera,” says Mr. Skoropadskiy.

Tensions over these historical issues are real enough, especially in the more Russified eastern Ukraine – where everyone’s grandfather served in the Red Army – and they may be part of the explanation for the very high first round vote for Volodymyr Zelenskiy, a Russian-speaker from eastern Ukraine who plays down nationalist themes.

“During the past five years the government made more steps [to legitimize figures like Mr. Bandera] than much of society is willing to accept,” says Mr. Likhachev. “Most of society feels we don’t need Lenin or Bandera. But you can’t really mobilize people politically with these issues. There has been no big public movement against it.”

More significant is the strong attraction these new radical right groups seem to exercise over Ukrainian youth. They articulate a cause. They have slick promotional materials and maintain a big infrastructure of sports clubs, training camps, and regular activities.

“I see how many young people want to be part of a movement,” says Ms. Movchan. “It’s kind of fashionable these days to join something, and here they are with all kinds of tools of recruitment, such as fight clubs, training grounds, and parades. They bring out the worst emotions, like homophobia and racism, to channel their aggression. I wish we could broaden our own audience to show young people there are other ways to be active, like fighting for human rights.”

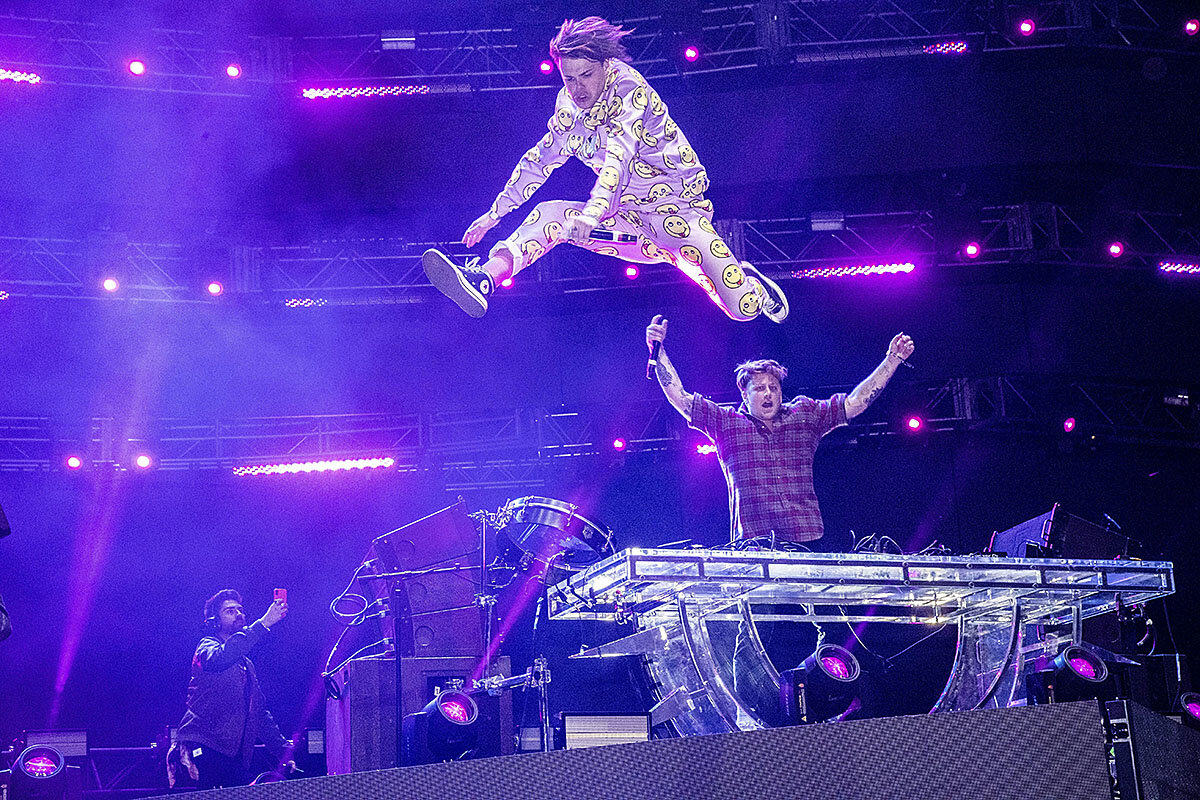

Harassment at Coachella: How musicians are fighting back

Harassment’s patterns are often detectible. When artists playing music festivals and their fans started to notice those patterns, they wondered: Will people listen if we call them out?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Stephen Humphries Staff writer

When California-based music festival Coachella was called out last year by a reporter who experienced some two dozen unwanted advances, the rebuke sunk in. Organizers at this year’s event, which is underway, have prioritized a new approach to fight sexual harassment.

In recent years, several campaigns have sprung up to educate concertgoers, musicians, and venues on how to make shows safer for women. Founded by musicians and music fans, the campaigns include the U.K.-based Safe Gigs for Women, the Boston-based Calling All Crows, and the Chicago-based Our Music My Body. Something they have in common: They’re helmed by millennials who are tired of complacent attitudes toward what happens at shows once the lights go down.

Despite success stories like Coachella, leaders of these groups say they still face resistance from festivals and venues. This year, Calling All Crows will present its case to the annual Event Safety Alliance conference. “It’s a safety and security issue,” says executive director Kim Warnick. “Why do you have an active shooter protocol but no sexual assault protocol?”

Harassment at Coachella: How musicians are fighting back

After last year’s Coachella music festival, one story generated almost as many headlines as Beyoncé’s towering performance from atop a crane: A reporter for Teen Vogue detailed how she’d been groped 22 times. Fifty-four other women told her they’d been sexually harassed during the event in Indio, California, whose 250,000 attendance skews 54 percent female.

The annual festival, which recently kicked off the first of its two consecutive weekends, has responded by prioritizing a new campaign against sexual harassment. For thousands of female attendees – resplendent in daisy crowns, fedoras, and cat-ear headbands (a nod to headliner Ariana Grande) – it’s a welcome step.

Fortunately for Coachella’s parent company Goldenvoice, several organizations reached out to offer guidance. In recent years, several campaigns have sprung up to educate concertgoers, musicians, and venues on how to make shows safer for women. Founded by musicians and music fans, the campaigns include the U.K.-based Safe Gigs for Women, the Boston-based Calling All Crows, and the Chicago-based Our Music My Body. Something they have in common: They’re helmed by millennials who are tired of complacent attitudes toward what happens at shows once the lights go down.

“As more people share their story, less people are willing to ignore it or excuse it,” says Maggie Arthur, co-leader of Our Music My Body. “When I first told my mom about this campaign ... she was kind of surprised that we were taking the time because she was kind of like, ‘That’s been happening since forever.’ ”

First step: surveys

Most of the campaigns narrowly predate the #MeToo movement. As such, communicating their message often felt as effective as conducting a conversation next to a stack of amplifiers. In 2016, Ms. Arthur, an educator at Resilience, a rape crisis organization, partnered with Matt Walsh of Between Friends, a domestic violence agency. They begun cold-calling Chicago-area festivals to offer their expertise in crafting sexual harassment policies, educating festivalgoers about consent, and training staff in how to assist victims of assault and misconduct.

“The overwhelming response was, ‘Well, sure we could see that that’s happening, but it’s definitely not happening at our festival,’” says Ms. Arthur. Her response? “Let us just come and talk to people and see if that’s true.”

Our Music My Body launched a two-week online survey in 2017 in which 509 male, female, and LGBTQ participants anonymously reported 1,286 instances of groping, receiving unsolicited comments about their bodies, and being aggressively hit on. In Boston, a similar 2018 survey by Calling All Crows reported 1,006 incidents of harassment or assault by 686 respondents. The organizations note that the unscientific surveys may be flawed, yet they yielded powerful anecdotal evidence to present to recalcitrant music venues.

Sadie Dupuis, singer and songwriter of the popular indie rock band Speedy Ortiz, has firsthand experience of harassment in a music culture that, she says, is “built upon alcohol sales and consumption.” She was in a crowd at a festival they’d played at when a stranger started harassing her, touching her, and not taking no for an answer. Onlookers failed to intervene when the situation escalated. Her status as a festival performer allowed her to flee to a backstage area policed by security.

“That experience made me think that we as performers – we have certain privileges and certain types of access that showgoers don’t have,” says Ms. Dupuis, who cranked up her Stratocaster against sexual harassers on last year’s pop-punk #MeToo anthem “Villain.” “So that’s why we set up a hotline that people can text if they are experiencing harassment. And in such a case we’re able to get someone from the venue on board to help out, or to bring the person backstage or to bring them out of harm’s way.”

During its 2015 tour, Speedy Ortiz also handed out flyers to educate fans about bystander intervention and de-escalation tactics in cases of sexual misconduct.

That same year, music fan Tracey Wise founded Safe Gigs for Women. The catalyst was a Manic Street Preachers show during which a fan lunged out, placed both arms around her, and pulled her into him. “It’s the last song,” was his feeble excuse.

Two game-changers

At the time, such efforts were novel. But, since then, there have been two game-changing moments for anti-harassment campaigns. The first one was the emergence of the #MeToo movement in 2017. Ms. Dupuis observes that she wasn’t the only artist writing songs about sexual consent shortly before the #MeToo movement took off. There was a collective shift in thought.

“It’s the same reason that any movement comes to a head: A lot of people have nearly identical experiences and are sick of putting up with it and are sick of a culture that puts up with it,” she says.

The second game-changer arrived a year ago.

“The biggest thing that I saw have an effect in the music industry was the Teen Vogue article on Coachella last year. Hands down,” says Kim Warnick, executive director of Calling All Crows, a music nonprofit focused on social activism founded by tour manager Sybil Gallagher and Chad Stokes of the band Dispatch. “Festivals after that article came out were much more willing to work with us. Goldenvoice responded to us immediately when we reached out.”

Ahead of this year’s Coachella, Goldenvoice also consulted with Our Music My Body (which now works with festivals such as Lollapalooza). Goldenvoice hired Veline Mojarro, a workplace sexual harassment expert, to spearhead its new “every one” initiative. It also tapped Woman, a Los Angeles consulting agency run by women whose Soteria program (named after the Greek goddess of safety) was deployed at the 2018 FORM festival in Arizona.

For every such win, Ms. Warnick still faces resistance from numerous festivals and venues. This year, Calling All Crows will present its case to the annual Event Safety Alliance (ESA) conference in November. Her pitch?

“It’s a safety and security issue,” says Ms. Warnick. “Why do you have an active shooter protocol but no sexual assault protocol?”

Steven Adelman, vice president of ESA, says the issue has hit home now that his 14-year-old daughter has started going to concerts, including those of Taylor Swift and Ms. Grande.

“The only way you can address a real problem is by shining a light on it,” says Mr. Adelman. “We’re working to fix it well because we do want people to go to shows and feel safe and leave with fond memories, T-shirts, and plans to go back next year.”

Tumbling into community: The ‘blossoming’ circus of Addis Ababa

When you get the chance to join a community circus for a day, you don’t say no. Our reporter found one that offers its artists, students, and audience a sense of possibility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As the rainstorm tap dances across the roof, two dozen children are hopping and tumbling across a squishy blue mat in the courtyard, jumping and falling with all the precision of popping popcorn. This is the Fekat Circus of Addis Ababa. And like the city itself, Fekat is many jumbled things at once. It’s a professional circus company, touring nationally and internationally.

Each afternoon, it transforms into circus school for children from the surrounding neighborhood, many of whom go on to join the troupe. And it’s a comfort: Fekat performers head to a nearby hospital every day, where they bounce from room to room, stealing noses, divebombing kids with puppet smooches, and blowing bubbles over the ward’s tiny, crowded beds. “We’re trying to be a community first and then a circus after that,” says co-founder Dereje Dange.

And today, a year after Ethiopia’s ruling party took a startling pivot toward reform, the sense of freedom and openness under the circus tent seems to be more common outside it, as well. “At the circus, people have a chance to see that things that they didn’t even imagine were possible really do exist,” says Mr. Dange.

Tumbling into community: The ‘blossoming’ circus of Addis Ababa

On a slate-colored April afternoon, Ethiopia’s capital is knee-deep in water. Rows of bug-eyed blue and white Soviet taxis slide slowly through the deluge, heaving a thick spray onto the sidewalks as all around them water bursts from the city’s seams, spilling out of clogged gutters and rushing through the cracks in walls and roofs and fences.

But down a steep cobbled street lined with bougainvillea, behind the aluminum-sheeted walls of a small compound, the show must go on.

As the rainstorm tap dances across the roof, two dozen children hop and tumble across a squishy blue mat, jumping and falling with all the precision of popping popcorn. “Good!” calls out an instructor. “Again!”

Every afternoon, whether the thin Addis air is dry or wet, the courtyard of Fekat Circus fills with children from the surrounding neighborhood, diving through hoops and flopping in and out of handstands as part of a daily crash course in the circus arts.

“For a lot of people, the circus is about escape,” says Dereje Dange, watching a string-beany girl wobble, giggling, out of a somersault, flipping her blue hijab out of her face as she goes. He would know. Before he co-founded Fekat, in 2004, he was a gymnast for the Ethiopian national team, teetering on the edge of burnout and looking for a less competitive way to do what he loved.

“But that’s not really the point for me,” he says. “We’re trying to be a community first and then a circus after that.”

That’s why each day, at 4 p.m., he hustles the performers in Fekat’s professional company off the stage and lays out mats to train whatever one or two or three dozen neighborhood kids feel like dropping by.

When they’re gone a couple hours later, Mr. Dange heads home, but doesn’t lock up. He doesn’t need to. A group of his performers lives here, at the back of the circus’s main office, which before it stored unicycles and clown noses had a long prior life as a Protestant church.

That’s par for the course in Addis, a city where layers of history are scrunched together so tightly they’re often hard to separate. In the neighborhood outside Fekat’s gates, for instance, the Italian art deco of the Mussolini era backs up into the concrete modernist office blocks of the infamous Derg military regime and octagonal, metal-roofed churches built by the Emperor Menelik II in the 19th century.

And like the city itself, Fekat is many jumbled things at once.

The circus, whose name means “blossoming” in Amharic, has a touring professional company. They travel around the country and the world, performing shows that weave together the universal elements of the circus – impossibly bendy acrobats, jugglers with an entire bowling alley of pins in the air above them – with uniquely Ethiopian storylines.

Think the Queen of Sheba, says Mr. Dange.

“Or the traffic of Addis Ababa,” he adds. “I want us to perform the stories that are in our lives, in our heads.”

That hasn’t always been easy for Ethiopian performers. The oldest members of his company still remember the brutal Derg era of the 1970s and ’80s, which killed or imprisoned hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians it deemed enemies of the state. In 1991, the regime was replaced by a stern one-party government, whose white-knuckled grip made many artists skittish about creative expression.

“There was a lid on our society,” Mr. Dange says. But a year ago, that same ruling party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), took a startling pivot. It appointed as its new prime minister a young, charismatic reformer named Abiy Ahmed. He immediately began a sweeping transformation, freeing political prisoners, reopening diplomatic relations with neighboring Eritrea, and appointing women to a variety of high-ranking political positions for the first time.

For the performers in Fekat, it felt like a new beginning, the country coming closer to the tiny, creative universe they had spent more than a decade building behind their brightly colored walls.

“At the circus, people have a chance to see that things that they didn’t even imagine were possible really do exist,” says Mr. Dange.

A mile away from the circus’s compound, meanwhile, in the scruffy seventh floor pediatric ward of Ethiopia’s largest hospital, another group of Fekat performers are acting out their own alternate universe.

The four Doctor Clowns – three humans and a ventriloquist puppet in polka-dot pajamas named Dr. Titi – bounce from room to room, stealing noses, divebombing kids with puppet smooches, and blowing bubbles over the ward’s tiny, crowded beds.

“Kids come here because their bodies need some kind of physical healing, but hospitals can break you mentally as well,” says Shimelis Getachew, who coordinates Fekat’s Smile Medicine Project, which visits the hospital daily. “That’s what we are here for.”

“Listen to your doctor,” Dr. Titi squeaks to one heavy-lidded girl. “She’s here to help you feel better!” Within seconds, he’s sending the girl and her parents into peals of laughter.

Back at Fekat’s compound the next day, Zahara Yasin is stretching after a morning of training. Like most of the professional performers, she got her start as one of the 7-year-olds flopping down on the mats here each afternoon.

At first, says Ms. Yasin, now 17, she didn’t tell her parents where she was going every day after school.

“I didn’t think they’d approve,” she says. But then she started to get good. So good that it was hard to keep a secret. And so one day a few years after she’d started, she invited her parents to a performance.

They were impressed to see her dart barefoot up a 30-foot pole and then dangle by one leg in a seeming duel with gravity. But even more than that, she says, they were taken by the way her fellow performers rallied around her “like a family,” she says. They gave her their blessing to continue.

Last year, Ms. Yasin, who is one of the circus’s only women, dropped out of high school to perform full time for Fekat.

It was a natural choice, she says. At school, she was someone average. Someone ordinary.

In the circus, there are no such limits.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Indonesia’s youth put candidates to the test

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One candidate wears jeans and rides a motorcycle. Another break-dances on stage. Welcome to campaigning for an election in Indonesia whose results may depend on older candidates winning the youth vote – and that could set a new course for the world’s third-largest democracy.

Candidates in the April 17 vote for president and a new legislature are very much catering to people under 35. Of the country’s 187 million eligible voters, more than a third are millennials who, according to a poll, want honesty and freedom from corruption in their leaders. After years of anti-corruption efforts under two presidents, Indonesia has made only slow progress. This need not be the case. According to a 2017 poll by Transparency International, 64% of Indonesians say ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption.

With that shift in attitudes, candidates in the 2019 election are competing to become the better corruption fighter. But first they must win over young people. Those voters are the least tied to past behavior and the most eager for honest, transparent government.

Indonesia’s youth put candidates to the test

One candidate for president wears jeans and rides a motorcycle. Another picked a running mate who break-dances on stage and earned millions by his 30s as an entrepreneur. Welcome to campaigning for an election in Indonesia whose results may depend on older candidates winning the youth vote – and that could set a new course for the world’s third-largest democracy.

Candidates in the April 17 vote for president and a new legislature are very much catering to people under 35. Of the country’s 187 million eligible voters, more than a third are millennials. Besides attempts at youthful appeals on the stump, candidates know exactly what young voters expect. According to a poll by the Alvara Research Center, they want honesty as well as freedom from corruption in their leaders.

That could be a big ask in a country known for a pervasive culture of corruption. After years of anti-corruption efforts under two presidents, Indonesia has made only slow progress. This need not be the case. According to a new survey by the International Monetary Fund, several countries have made significant progress against corruption in a relatively short period. “These countries reached a ‘tipping point,’ often as a result of a broad-based domestic consensus or an external push to aggressively fight corruption,” the report stated.

The key lies in convincing citizens to pay taxes. The most corrupt countries are those that collect the least in taxes, the IMF found in a survey of 183 countries. In many countries, paying bribes to tax collectors can help lower a person’s tax bills.

The IMF found that Georgia, for example, was able to raise tax revenue by 13 percentage points after a vigorous campaign against corruption. Colombia, Costa Rica, and Paraguay have provided citizens with online tools to track spending on government projects. Chile and South Korea have cut corruption by moving to electronic procurement systems that enhance transparency and competition.

Since 2014, Indonesia’s president, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, has taken steps toward clean governance. And the Corruption Eradication Commission has investigated or removed hundreds of officials. But now voters expect more. According to a 2017 poll by Transparency International, 64% of Indonesians view their government’s efforts to fight corruption positively. And 78% agree that ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption.

With that shift in attitudes, candidates in the 2019 election are competing to become the better corruption fighter. But first they must win over young people. Those voters are the least tied to past behavior and the most eager for honest, transparent government.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Assault ‘is not your story’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lisa Andrews

Today’s contributor shares how the realization that we can never be outside God’s care inspired an idea that enabled her to safely escape an attempted assault and to move forward with peace and confidence rather than a sense of fear or victimization.

Assault ‘is not your story’

It was a Saturday night early on in my semester abroad in a European city. I had stayed out very late enjoying the company of new friends. My roommates were doing other things that night, and it didn’t hit me until I reached my tram stop that I’d have to walk back to our apartment alone. I quickened my pace along the several dark, empty blocks and stopped in a lighted phone booth outside the apartment building to fish out my keys.

As I fumbled in my purse, my back to the phone booth entrance, a voice behind me suddenly murmured “Hello.”

I turned to find a large man blocking the doorway. I could tell by the way he was looking at me that he wasn’t there to be friendly. My stomach sank in fear as I said something about needing to leave. He didn’t budge. Instead, he tried to kiss me and reached for the waistband of my jeans. I was able to move backward and block his hands, but I knew I couldn’t keep him away for long.

In the next moment, though, my fear was completely replaced by a feeling of calm, absolute strength. A clear message filled my thought, almost as though it had been spoken aloud: “This is not your story.” It was an immediate, tangible realization that I wasn’t actually alone. God, who I understand as the ever-present, entirely good and loving, divine Father-Mother of us all, was right there, keeping me safe.

The man was still inches away from me, but it was almost as if I could see above the situation. Simple instructions came into focus: The next time he reached for me, I would duck and run out under his outstretched arms. He came toward me, and I was able to dive out of the booth, ending up on the sidewalk. I got up quickly, and when I looked around, the man was gone.

Slightly shaken but feeling extremely grateful, I let myself into my apartment and got ready for bed. The message I’d received in the phone booth – “This is not your story” – was a helpful guide in how to think about what had just happened. I would not dwell on the frightening moments or explore the “what ifs” of what might have occurred. Instead, I could move forward with the true story, the spiritual fact that remains unchanged regardless of the situation: that God, good, is the reliable source of our safety, and no one can ever really be outside of Her care.

It occurred to me that another important aspect of moving forward was seeing that man differently. While his actions would label him as a victimizer, my study of Christian Science had taught me that this was not his story either. The true, spiritual identity of each individual is God’s spiritual image and likeness – the image and likeness of pure good. So, just as God did not create a vulnerable woman, He could not create an abusive man. While what that man had tried to do certainly wasn’t right, I felt that I needed to mentally place him under God’s care too. Everyone has the innate ability to wake up to his or her real identity, free from any violent or impure impulses.

These prayers brought me enough peace to fall asleep that night and to continue my wonderful semester abroad with complete confidence and freedom. I did make sure to not be out alone late at night again, but I also brought an increased understanding of God’s protecting care to all my activities.

This experience has been an important support for me in the years since, as I’ve lived in a city, taken public transportation, traveled, and interacted with men free from any feeling of trauma. It’s also given me a way to respond when I hear accounts of harassment or assault: I pray that all women and men can know and feel that “this is not your story.” The reality, always, is that our spiritual identities are our real identities – untarnished, protected, loving, and loved – and that “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble” (Psalms 46:1).

Adapted from an article published in the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, Nov. 15, 2018.

A message of love

Un trésor en flammes

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow for a report from Syria. The Kurds’ hard-won political autonomy in the country’s north and east has an enhancer: a university that has come to represent the dreams of a generation of Kurds eager to help strengthen their society.