- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- US sanctions on Iran, Venezuela: Is regime change the whole story?

- Uncle Sam on Instagram: How Army adapts recruiting pitch for Gen Z

- Why black millennials are seeking faith at music festivals

- For ISIS brides and children, coming home is not an option

- From Blue Apron to HelloFresh, how green are meal kits?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The Mueller report as a challenge for democracy

Maybe the Mueller report is a challenge for democracy to solve.

This idea isn’t original to us. It comes from a thought-provoking essay on the site Lawfare by Yale Law School Prof. Samuel Moyn.

Democracies sometimes face a difficult balancing act, Professor Moyn writes. They have to allow serious oversight of government. But they also have to keep that oversight from becoming political opposition by other means.

Congress has the power to strike this balance. But in recent years it hasn’t. There’s been partisanship and vacillation instead. An exception that proves this rule: the 9/11 Commission, which investigated U.S. anti-terror protections with broad bipartisan support.

Independent and special counsels have stepped – or been thrown – into this breach. But they’re not well-suited to judge broad patterns of governance, writes Professor Moyn. They can pursue targets too long and too far. If they file charges, political opponents of those implicated can try to use them to overturn the results of elections.

What does this mean in terms of the special counsel? It means that by taking a conservative approach to prosecutions, Mr. Mueller may have primarily exposed not the president but the lack of U.S. institutions to handle such situations.

Is his report a roadmap for impeachment? Is it not? That is for democracy to solve. Mr. Mueller appears to have concluded that the future of the country depends less on impeachment referral than “on letting democracy do its work when it comes to Trump, and doing better in the future with squaring the circle of accountability and partisanship,” Professor Moyn writes.

Now to our five stories for the day, which include a look at what comes next now that the U.S. has turned the dial on Iran sanctions to 11 and how black millennials are increasingly turning to faith for guidance.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

US sanctions on Iran, Venezuela: Is regime change the whole story?

The imposition of harsh U.S. oil sanctions on Iran and Venezuela seems to be nakedly seeking to force regime change. But there’s no precedent for that working so simply, suggesting something else might be at play.

The Trump administration is levying some of the heaviest sanctions ever against Venezuela and Iran. This week Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced the U.S. will impose sanctions on all countries purchasing Iranian crude, to drive Iranian oil exports to zero. For many experts in the uses and limitations of economic sanctions, the clear objective of the Trump administration in both cases is regime change.

At the heart of the policies is a rejection of the traditional use of sanctions as one of a number of diplomatic tools to elicit concessions, experts say. In its place is instead an unprecedented conception of sanctions as a bludgeon to force surrender. For some analysts, this is rooted in practices honed by President Donald Trump over his long business career as well as his perceptions of U.S. economic power.

But there is no precedent to suggest that sanctions, no matter how draconian, ever work to force regime change, the experts add. “We know from all kinds of examples that using sanctions by themselves is not particularly effective,” says Jim Walsh, an expert at MIT. And that, he says, suggests the U.S. might have another objective.

US sanctions on Iran, Venezuela: Is regime change the whole story?

At first blush, Caracas and Tehran may seem to have little in common.

But for the Trump administration, the governments in the capitals of South America’s Venezuela and Persian Iran are practically two peas in a pod – oppressors of their own people and malign actors in their regions – and they need to go.

And so, despite a foreign policy that is otherwise for the most part leaving authoritarian rulers alone, the United States under the Trump administration is levying some of the heaviest sanctions ever against the socialist regime of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela and the ayatollah-overseen Islamic republic in Iran.

Just this week, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo took the world – and specifically a number of key U.S. partners – by surprise in announcing that as of next week (May 2), the U.S. will no longer grant waivers to countries importing Iranian oil and will begin imposing sanctions on countries that continue to purchase Iranian crude.

Since President Donald Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal last year, the U.S. had been waiving sanctions on a list of major Iranian oil importers, including China, India, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey.

The intent of ending the waivers, Mr. Pompeo said, is to drive Iranian oil exports to zero.

That stated goal had a familiar ring, as the Trump administration has also imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s state-owned oil company PDVSA in order to dry up the Maduro government’s lifeline of oil exports.

The Trump administration has made no bones about its objective in Venezuela: use sanctions to bring down President Maduro and replace him with opposition leader and self-declared legitimate president Juan Guaidó. In the case of Iran, on the other hand, the U.S. says it is aiming for a more modest change in behavior by a regime it considers to be the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism.

But for many experts in the uses and limitations of economic sanctions, the clear objective of the Trump administration in both cases has an unequivocal name.

“With both Venezuela and Iran, it’s clearly regime change they are after,” says George Lopez, an expert in economic sanctions and security and professor emeritus of peace studies at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. “There’s really no policy change either target could undertake that would please this administration enough to reverse their unilateralist actions.”

That said, there is simply no precedent to suggest that sanctions, no matter how draconian, ever work to force regime change, the experts add.

“If ‘working’ means we impose costs, then yes, we can impose costs, and even severe costs,” says Jim Walsh, a senior research associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Security Studies Program in Cambridge and an expert in the effectiveness of sanctions in addressing Iran’s and North Korea’s nuclear programs.

“But if by ‘working’ we mean getting them to bend to our will and capitulate, that’s less clear. And in terms of changing behavior,” he adds, “we know from all kinds of examples that using sanctions by themselves is not particularly effective.”

Others are even more categorical. “There is simply no precedent for an externally driven economic implosion to trigger a successful transition away from a well-entrenched authoritarian regime towards a durable democracy or enhanced regional stability,” said Suzanne Maloney, an Iran expert and deputy director of the Brookings Institution’s foreign policy program, in a Brookings analysis of Secretary Pompeo’s announcement Monday.

At the heart of the Trump administration’s Iran and Venezuela policies is a rejection of the traditional use of sanctions as one of a number of diplomatic tools to resolve a conflict or elicit concessions from an adversary, sanctions experts say. In its place is instead an unprecedented conception of sanctions as a bludgeon to force an adversary’s surrender.

For some analysts, this shift in the use of sanctions has its roots in practices honed by Mr. Trump over his long business career as well as in the president’s perception of the U.S. economy and America’s unrivaled role in global financial markets as his ultimate weapon for unilaterally forcing change.

“Trump’s view of sanctions is that when you’re the economic strongman, you can put your foot on the throat of any target, and sooner or later they will capitulate because they have no other choice,” says Professor Lopez. “He has held that view in his personal business activities,” he adds, “and now he’s applying it in foreign policy, backed up by his view that until now the United States’ economic strength has not been used properly or to the full extent possible.”

Some international financial experts say Mr. Trump is overplaying the U.S. hand in international economics with his maximalist use of sanctions. They warn that the Trump administration could end up weakening U.S. global clout by driving allies and adversaries alike to seek out alternatives to U.S.-dominated international financial systems.

And while sanctions experts point out that Mr. Trump’s original national security team opposed a unilateralist use of sanctions – particularly secondary sanctions that also punish allies and partners – they note that the president has found an avid supporter of his vision of sanctions in national security adviser John Bolton.

Indeed, Mr. Bolton has long called for outright regime change in Tehran, and his is one of the most fervent voices demanding Mr. Maduro’s departure.

It’s not that sanctions don’t work, experts say; it’s rather that history shows they don’t work alone, and maximalist use tends to prompt entrenched adversaries to hunker down and hard-liners in a regime to carry the day over moderates more inclined to consider concessions as part of diplomacy.

As Ms. Maloney at Brookings notes, Iranian leaders who traditionally had been “loath to negotiate” suddenly felt an urgency to reach an accord with the U.S. and other international parties over Iran’s nuclear program after the Obama administration imposed “then-unprecedented measures” between 2010 and 2013.

What Iran’s willingness to negotiate demonstrated, she says, is that “the logic that severe pressure can force a recalcitrant Tehran to yield is itself not wholly unrealistic.”

Other experts note that sanctions have played a role in ending civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone and in stabilizing Ivory Coast’s democracy.

But they emphasize that sanctions worked in those cases, as they did with Iran, only as part of a diplomatic package of carrots and sticks and not as a unilateralist blunt-force weapon.

“The incentives side of sanctions almost always kicks in at the end, to get concessions that you otherwise can’t get, but that step is always there,” says Professor Lopez. “But if you look at what we’re doing with Iran and Venezuela right now, it seems that’s a step too far for this administration.”

Indeed, the Trump administration is not interested in imposing sanctions as others have in the past in the cases of Iran and Venezuela because it is not interested in the traditional outcome of concessions and incentives, some experts say.

Secretary Pompeo has outlined a 12-point plan of actions Iran could follow to win full relief from U.S. sanctions. But as MIT’s Dr. Walsh says, “It’s one thing to use diplomacy to make demands of an adversary to start modifying behavior; it’s another thing to go after the identity of a country. And if you look at Pompeo’s 12 points,” he adds, “it’s really saying ‘We want nothing less than a complete change in the identity of the Islamic republic of Iran.’”

In any case, Dr. Walsh says he doubts the White House plan for Iran is regime change or bust. Instead, he suspects the White House, knowing that regime change through sanctions is a long shot, has a Plan B to use the oil sanctions to goad Iran’s hard-liners into forcing the regime to take steps that would open the door to U.S. military action.

“My hunch is that the real purpose of all of this is to force the Iranians into a corner where they have no choice but to pull out of the JCPOA,” the nuclear deal Iran is still honoring despite the U.S. withdrawal, he says. “And if they do that and follow up with something to save face, like installing new centrifuges or ramping up enrichment,” he adds, “that gives us the opportunity to use military force against those facilities.”

Uncle Sam on Instagram: How Army adapts recruiting pitch for Gen Z

Long-running wars and low unemployment mean fewer young people enlisting in the military. So the Army has turned to big cities and social media, where its message of patriotism and service is finding new listeners.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The Army fell short of its recruiting goal by 6,500 soldiers last year. Facing a quota of 68,000 new soldiers this year, top officials have expanded the Army’s social media recruiting campaign to court the digital natives of Generation Z.

The push on Instagram and other platforms attempts to appeal to a younger sensibility by infusing its message with humor and touting what the Army has to offer beyond combat. Sgt. 1st Class Dario Franco, a recruiter in Northern California, has posted memes on Instagram featuring pugs, Rihanna, and Spider-Man to deliver the Army’s sales pitch.

Arleth Aguilar, who will graduate from high school in June, was amused enough by his page to contact him via the social media platform. His posts “made me curious about being an insider of those jokes,” she says. A few weeks ago, she enlisted.

Sergeant Franco points out that his visits to high schools, career fairs, and community events yield more recruits than his online posts. But, he adds, “Social media helps us get the message out there. Then it keeps it out there until a person feels ready to take the next step.”

Uncle Sam on Instagram: How Army adapts recruiting pitch for Gen Z

Arleth Aguilar had mulled the idea of joining the military for several years by the time her half-brother enlisted in the Army earlier this spring. He sent her a link to his recruiter’s Instagram profile page, and there she saw the Army’s sales pitch delivered through memes featuring pugs, Rihanna, and Spider-Man.

The unexpected humor intrigued her enough to begin trading messages with the recruiter, Sgt. 1st Class Dario Franco. For Ms. Aguilar, who lacked phone service at the time, the ability to ask questions via the social media platform proved essential in helping her reach a decision. She signed up a few weeks ago and will report to basic training after graduating high school in June.

“Social media has a big impact on my life, and I think having that as a way of communication makes it a little more comfortable to talk to people,” Ms. Aguilar says. The informal tone of Mr. Franco’s Instagram posts “made me curious about being an insider of those jokes.”

Her enlistment story reflects the Army’s growing emphasis on social media as the service tries to court the digital natives of Generation Z and rebound from a recruiting deficit of 6,500 soldiers last year.

The expanded marketing campaign on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms attempts to appeal to a younger sensibility by infusing its message with humor – less Uncle Sam, more Will Ferrell – and touting what the Army has to offer beyond combat.

The shift away from traditional recruiting methods of television ads and phone calls occurs as the Army faces a steep climb toward this year’s goal of 68,000 new soldiers. In addition to recruiters posting memes and selfies, ads on social media and gaming platforms target digitally-savvy youth by promoting the Army’s array of tech and engineering jobs and its recently formed e-sports team.

“The military – the country – has been at war since 2001,” says Lisa Ferguson, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Army Recruiting Command based at Fort Knox in Kentucky. “So there are a lot of misperceptions about the Army. It’s not just infantry and busting down doors in Iraq. There are more than 150 career fields.”

An estimated 71 percent of Americans between 17 and 24 are ineligible to serve in the military for reasons that include obesity, mental health conditions, criminal offenses, and drug use. Meanwhile, a strong economy, with an unemployment rate below 4 percent, has siphoned off potential recruits.

The Army spent an extra $200 million on enlistment bonuses and eased admission standards last year in an effort to fulfill its recruiting quota. The service has bolstered its search for future soldiers this year by funneling more resources to almost two dozen big cities – ranging from San Francisco and Seattle to Boston and Philadelphia – located outside the historical recruiting strongholds of the South and Southeast.

“There’s something to be said for realizing there are qualified youth all over the country,” says Beth Asch, a senior economist with the RAND Corporation and an expert on military recruiting. “People in the U.S. are uninformed about what the military profession involves. If you’re not going into those cities to recruit, you’re going to have a harder time changing minds.”

A digital learning curve

Sergeant Franco works in an Army recruiting office that shares space in a strip mall with Jamba Juice and Cold Stone Creamery in Vacaville, California. The town lies at the fringes of the San Francisco Bay Area, about a half-hour’s drive from his hometown of Napa. Familiar surroundings aside, he felt off-balance after arriving here as a new recruiter three years ago.

He gained his bearings by relying on his experience as an intelligence analyst. In that role, Sergeant Franco, who deployed with the Army to Iraq and Afghanistan, collected and assessed data on known and potential threats in his unit’s areas of operation.

As a recruiter, he turned his analytical skills toward the region’s young adults, deciphering how to connect with them. A 2004 high school graduate who enlisted the next year, he recognized that tech’s rapid evolution required him to adopt strategies that differ from recruiting methods back then.

“Calling people was still something that was done when I signed up. But nobody has landlines anymore, and with caller ID, if they don’t know the number, they’re not answering,” he says. So instead of making cold calls for hours a day, when someone “likes” one of his Instagram posts, Sergeant Franco follows up with an invitation to contact him.

If the online exchanges lead to a conversation, he explains, “the rapport is smoother because there’s been a back-and-forth before we sit down to talk. If I meet someone for the first time at a high school or an event, it can be a little more awkward. Or they’ll just avoid me. If we’ve messaged on Instagram, their comfort level seems to be higher.”

The Army has scaled a digital learning curve over the past two years as top officials seek to increase the active-duty force from 476,000 soldiers to 500,000 by 2022. Once wary of social media, commanders now direct recruiters to post across platforms and engage their audiences, urging them to use humor and offer glimpses of their lives out of uniform.

“It’s important to show that it’s not all green, all the time,” says Lt. Col. Michael Firmin, who commands the Army’s Northern California recruiting battalion. Based outside Sacramento, the unit covers an area that extends into western Nevada and southern Oregon. “One thing we’ve realized is that young people don’t necessarily know that you’re not always in uniform. We want to make sure they understand it’s not Army, Army, Army all the time.”

Sergeant Franco’s Instagram page mixes memes that highlight the service’s education benefits and variety of career paths with photos of him hiking and playing with his two young sons. For all the focus the Army has placed on social media, he points out that his visits to high schools, career fairs, and community events yield far more recruits than his online posts.

But unlike public appearances, social media content lives forever. Both Ms. Aguilar and her half-brother, Steven Lopez, who shipped out for basic training earlier this month, spent time on Sergeant Franco’s Instagram page before contacting him. He has heard from some eventual recruits months after they first came across him online.

“Social media helps us get the message out there,” he says. “Then it keeps it out there until a person feels ready to take the next step.”

Belonging to a larger cause

The Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy each reached its recruiting quota last year. The struggles of the Army, which requires more than twice as many enlistees, prodded top commanders to redouble recruiting efforts in 22 metro areas that the service long has treated as an afterthought.

The return on that investment will remain unknown until the Army announces its recruiting totals later in the year. Dr. Asch, with the RAND Corporation, regards the move as a worthwhile gambit as the Army seeks to reverse last year’s shortfall.

“These are cities with large populations of young people, and if you go in and inform them about the military, you could see the chances of recruiting them improve,” she says.

The stronger push into Los Angeles, Sacramento, and other cities coincides with a related strategy. “The military in general, and the Army in particular, is trying to tailor recruiting messages to specific geographic areas,” Dr. Asch says. “There has been a realization that the same message doesn’t necessarily work everywhere.”

Last fall in Chicago, the Army launched a recruiting pilot program with online ads aimed at young adults in neighborhoods across the city. Researchers found that ads describing the Army’s pay and health care benefits resonated with youth in working-class areas. Young residents in affluent neighborhoods, by contrast, responded to ads emphasizing leadership and travel opportunities.

Sergeant Franco has discerned differences in career interests across his recruiting territory. People who live in Napa gravitate toward the Army’s infantry and information technology positions. In Vacaville and nearby Dixon, where Ms. Aguilar attends school, they favor engineering and health care.

The diversity of careers within the service pops up as a recurring theme on Mr. Franco’s Instagram page. “People think the Army is only infantry and tanks,” he says. “But there are cooks, engineers, fuel specialists. So it’s a matter of educating people.”

At the same time, given the country’s long-running wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the steady rotation of Army units to conflict zones around the world, recruits must accept the almost certain prospect of serving overseas irrespective of their position.

“The military is about fighting wars,” Dr. Asch says, “and when you join the military, you’re an asset who can be deployed. That said, there are a lot of occupations that contribute to the mission that aren’t infantry, and generally speaking, going overseas and doing your job – people want that.”

The sentiment holds true for Ms. Aguilar. She enlisted to obtain education benefits to pay for college in a few years. Before then, she wants to belong to a larger cause.

“I was told by many people that joining the military shouldn’t be an option, that I should pursue college,” she says. “But the thought of serving my country, helping people, and just giving back – that’s what grabs me the most.”

Why black millennials are seeking faith at music festivals

The decline in churchgoing in the U.S. is well known, but it doesn’t preclude religious talk in general. African American millennials are one group seeking outlets. How might venues like music festivals afford them a voice?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Candace McDuffie Contributor

Music festivals are not the place you’d expect to find people going to church. But this Sunday will make two weeks in a row when a service has taken place at such a venue.

Some of that has to do with the faith of the musicians involved, but it is also the result of a greater effort to reach African American millennials and give them an outlet for their spirituality. That effort is creating conversations in comfortable spaces, like concerts and college campuses.

This weekend, the discussion moves to singer and entrepreneur Pharrell Williams’ inaugural Something in the Water festival in Virginia Beach. One aim of the event is to engage religious young people, and it will feature a panel discussion about black millennials and religion and a pop-up church service open to the public.

Theologian, writer, and educator Candice Benbow maintains that this is a step in the right direction. “As black millennials have gotten older, we’ve gotten more comfortable with the ability to say ‘My faith looks different than my mom’s faith or my dad’s faith, and I am still spiritual.’ That’s completely different than what we were raised to think was possible.”

Why black millennials are seeking faith at music festivals

When singer and entrepreneur Pharrell Williams’ inaugural music festival kicks off this weekend in Virginia Beach, it will include a high-profile list of performers including Missy Elliott, Gwen Stefani, and Busta Rhymes. But it will also feature something else: spirituality.

From a talk with alternative medicine advocate and author Deepak Chopra to a pop-up church service, faith will be an important theme at Something in the Water, reflecting a yearning observers say exists among these concertgoers for ecclesiastical interactions regardless of the venue.

Black millennials in particular are seeking such opportunities, prompting more church time at music events – Kanye West led a service last Sunday at Coachella – and efforts to reach them from organizations such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The museum’s conversation series, gOD-Talk, will also be at Something in the Water, encouraging discussion about black millennials and their religious beliefs. This type of talk offers a chance for those involved to reclaim their narrative, says one leader.

“Many times people are theorizing or pontificating about the habits of black millennials: We’re destroying things; we’re racked with debt. The beauty of gOD-Talk is that we are giving them agency,” says Teddy Reeves, the curatorial museum specialist of religion in the Center for the Study of African American Religious Life, part of the NMAAHC. “Our relationship with religion is complex and nuanced, and with this series we are working to chart our own territory.”

The Pew Research Center discovered that black millennials are more religious than other millennials, though fewer than 4 in 10 say they attend services weekly. Theologian, writer, and educator Candice Benbow has collaborated with gOD-Talk in the past and is appearing on its panel at Something in the Water. She says that the increase of unconventional religious black millennials is a direct result of the current sociopolitical climate.

“We are currently experiencing a movement moment, right? There’s Black Lives Matter, Me Too, Times Up. Millennials have walked away from organized religion because it’s been rooted in a lot of pain and trauma,” says Ms. Benbow, who hosts her own podcast, Red Lip Theology.

“How do I make sense of faith when people who are at the helm of religious leadership are being exposed? How do I contend with religious ideologies when we keep getting shot down in the street and the police who are killing us continue to be acquitted? These aren’t just cultural questions; they’re existential as well,” she says.

Part of the mission of gOD-Talk is to reveal how millennials, specifically black millennials, are interacting with religion. The project, which overall studies the “totality of the African American religious experience,” according to Mr. Reeves, is spearheaded by his center in association with Pew. It has participated in events at churches, museums, and colleges across the country.

“If black millennials are leaving traditional religious spaces, whether they are Christian or Muslim or Jewish or Buddhist, then where are they going?” Mr. Reeves says. “Pew’s data shows that there is a rise in the unaffiliated group, yet many still believe in God. There has also been a rise in young people claiming to be spiritual and not religious. We wanted to figure out what was going on, how this impacts our religious institutions going forward, and what this means for future generations.”

Unlike Mr. West’s Sunday service on the final day of Coachella, which was open only to festival ticket holders, the pop-up at Something in the Water will be free and open to the public. It will also consist of more than just a gospel choir; there will be a dance ministry, prayer offerings, and national worship leaders sharing the word. Mr. Williams’ uncle and the leader of Faith World Ministries, Bishop Ezekiel Williams, who will be participating in the service, told Norfolk’s ABC affiliate 13 News Now earlier this month why his nephew decided to engage in such an undertaking.

“At the root of Pharrell, he’s a secular artist. Of course, we know, but at his very core, he’s a very very spiritual individual. He’s very serious about God,” said Bishop Williams. “He remembered as a young boy pop-up church tent revivals and things like that that you would pass, and they seemed so energetic and spirit-filled.”

Using the festival as a backdrop for a service is a strategic move. “Some people are apprehensive, and they won’t cross the door, the threshold,” Bishop Williams continued. “They won’t come into the worship service, and so we tried to bring the service to them.”

Something in the Water aims to engage young religious folk where they are comfortable and feel free to be themselves. Ms. Benbow maintains that this is a step in the right direction. “As black millennials have gotten older, we’ve gotten more comfortable with the ability to say ‘My faith looks different than my mom’s faith or my dad’s faith, and I am still spiritual.’ That’s completely different than what we were raised to think was possible.”

A deeper look

For ISIS brides and children, coming home is not an option

When erstwhile members of ISIS are left adrift, should a society keep them at arm’s length, or reengage to rehabilitate or prosecute them? And what of their children? Much of the West is wrestling with just these issues.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Dominique Soguel Correspondent

At its peak, the so-called Islamic State controlled a landmass roughly the size of the United Kingdom and ruled over 11 million people in Syria and Iraq. Today its followers are homeless, many living in camps in northeast Syria, after ISIS’s territory was retaken. And hundreds of foreign women and children who used to call the aspiring state home are now weighing returns to their countries of origin in the West.

Many of those countries are resistant, including Britain, France, and the United States. But some experts argue that it is the best route forward. “Countries should take responsibility for their own citizens,” says Daniel Byman, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy. “This is especially true for countries with strong legal systems like the United States.”

Failure to repatriate and put ISIS remnants through the legal system will simply encourage other nations to shirk their responsibility vis-a-vis their citizens stuck in Syria, argues Mr. Byman. It will also make the long-term situation more dangerous, as jihadists will try to hide out and turn to militant groups for support and protection.

For ISIS brides and children, coming home is not an option

While the so-called Islamic State has been ousted from the territory once called its caliphate in northeast Syria, how firmly it remains dug into the minds of its former followers, especially those followers who crossed the world to join, remains a concern for many.

Concentrated in camps of northeast Syria not far from the Turkish and Iraqi borders, the former citizens of the ISIS state include men, women, and children. Fenced off from the rest by their Kurdish keepers are hundreds of foreign women and children who were once inhabitants of the aspirant state and are now left adrift. Many are weighing a return to their countries of origin in the West.

But in doing so, they raise a host of issues for their native lands. Those include whether and how to reintegrate adults, who at least for a time were steeped in ISIS’s anti-Western dogma, and what to do with their children, most of whom are too young to even understand the political obstacles keeping them in a camp where resources are scarce and infant mortality high.

Handling these people “requires special security measures. This requires international agreement on judicial proceedings,” says Farhad Youssef, a member of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), as he sits on a plastic chair outside a military base near Ain Issa, a camp holding ISIS foreigners displaced in earlier offensives. “The children, the second generation of ISIS, need cultural centers and rehabilitation opportunities. This is an international problem, and their home countries have to step up to the plate.”

‘Everyone despises them equally’

But for the most part, those home countries are in no rush to do so.

At its peak, ISIS controlled a landmass roughly the size of the United Kingdom and ruled over 11 million people in Syria and Iraq. Tens of thousands of foreigners crossed the porous borders of Turkey to join: men bent on jihad, women seduced online, and even families drawn by the moral order presented in glossy online magazines and other forms of Islamic State propaganda.

The International Center for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) at King’s College London estimates that 41,480 people – including 4,761 women and 4,640 children – from 80 countries were affiliated with ISIS. Some have died convinced of their ideas. Others changed their minds and made it home to face justice. The foreigners who have survived and stayed until the end, falling back with the group amid battlefield losses, are widely seen as the most ardent of ISIS supporters. Foreign minors, according to the researchers, “possess the ideological commitment and practical skills to pose a potential threat upon return to their home countries.”

The Kurdish-led SDF have signaled for months that they do not have the capacity or the appetite to bring to justice or care for all the foreigners who have come under their custody. But there has been huge reticence from Western countries and other nations to take responsibility for their citizens and former residents.

Earlier this year the British home secretary, Sajid Javid, revoked the citizenship of Shamima Begum, who joined the group at age 15 and lost three of her children in Syria. France, meanwhile, is hoping to route its citizens who joined ISIS to Iraq for prosecution, despite concerns from both counterterrorism experts and human rights groups. Fourteen French suspected ISIS members, some of them of Arabic origin, are now on trial in Baghdad after having been extradited from Syria.

In the United States, Washington has refused to readmit Hoda Muthana, an American-born daughter of a Yemeni diplomat who traveled from Alabama to Syria to join ISIS. The government claims that neither she nor her son are Americans because her father was a diplomat for Yemen at the time of her birth and children of diplomats are not entitled to birthright citizenship. Her lawyers dispute that, arguing her father had lost his diplomatic status before she was born, and note that she had been granted a U.S. passport.

Ms. Muthana made the decision to go to Syria in 2014, a time when ISIS was at the height of its propaganda offensive, releasing grisly videos of beheadings. Hassan Shibly, a lawyer for Ms. Muthana’s family, says ISIS recruiters found her on a benign Muslim-only forum and then radicalized her through direct communications. The social media account under her name praised the killings of Westerners.

Mr. Shibly says that whatever her legal situation, Ms. Muthana and her son are caught between a rock and a hard place. Her father wants her back; her mother wants the same but is no longer on speaking terms with her daughter.

“It is important to understand that the average American Muslim and the average world citizen is on the same page when it comes to hating ISIS,” Mr. Shibly says. “Everyone despises them equally. So it is quite horrific when a parent learns that a child joined ISIS. There is concern she was brainwashed and groomed. At the same time they feel she should have known better. They are very, very hurt by these decisions that she took and the approach that she took.”

The argument for bringing them home

Experts such as Daniel Byman, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy, say that Western nations are making a mistake by not taking their ex-ISIS women and children back. “Countries should take responsibility for their own citizens,” he says. “This is especially true for countries with strong legal systems like the United States.”

Failure to repatriate and put ISIS remnants through the legal system will simply encourage other nations to shirk their responsibility vis-a-vis their citizens stuck in Syria, he argues. It will also make the long-term situation more dangerous, as jihadists will try to hide out and turn to militant groups for support and protection.

It is possible, Mr. Byman says, for women and children to find a peaceful coexistence in Western societies even after the indoctrination and traumas they endured under ISIS. “Western societies regularly work with people who are family members of violent organizations, treating them as citizens and at times giving them extra support,” he says.

“For women, however, it is important to recognize that many women who went to Syria wanted to join ISIS or otherwise support the group. The assumption that ‘woman = victim’ is true sometimes but is often false,” he adds.

The children of ISIS are particularly vulnerable, observers say. Save The Children warns that there are more than 2,500 children from 30 countries living in dire conditions in camps in northeastern Syria after fleeing the last patch of territory held by ISIS on the Iraqi border.

“All children who have lived under Isis control have experienced horrific events – violence, acute deprivation, and bombardment,” the charity said in an open letter to political leaders in Australia, which has up to 70 children born to foreign fighters in Syria. “Many have lost loved ones. And now they languish in dangerous camps in north-east Syria, where children are sick and malnourished, and there isn’t enough food to go around.”

Nadim Houry, the director of terrorism and counterterrorism programs at Human Rights Watch, says that the response of Western states and all countries of origin should be governed by the recognition that these children are victims: Whether they were taken to territory held by the Islamic State group, or born there, they are victims first of circumstances and decisions made by their parents. “It doesn’t matter if they are under ten or over ten,” he says. “There is a legal and moral duty on states to bring back these children to allow them a chance to live normal lives, to reintegrate and support them in that process.”

The precedent in international law, he adds, is very clear. Child soldiers are considered the victims of recruitment of adults. If these children joined ISIS but did not commit violent crimes themselves, there is little point in prosecution.

“If you look at how the West looked at child soldiers of Liberia and the conflicts, there should be no difference just because there is an ISIS label,” he says. “The majority of the children that I have seen in these camps are not ones who fought with ISIS; they are not even people who went to school under ISIS. It does not mean that they are not traumatized. ... The priority really should be to reintegrate them.”

The limits of disengagement

Out of European nations, France had the highest number of nationals joining ISIS, although on a per capita basis Belgium comes out on top. To date 67 adults, two-thirds of whom are women, and 82 minors have returned to France. There have been no plots carried out by returnees.

Children have generally been placed with relatives when possible and provided with extra support. There is not yet enough data on ISIS returnee children to determine whether efforts to help them transition back to a semblance of normality in Western societies are working.

As for the adults who stood by ISIS in its final hours, terrorism expert Jean-Charles Brisard doubts that they can be rehabilitated.

“Those individuals are the most determined of all, whether we are speaking of men or women,” he says. In France, there have been efforts to get such people either to “disengage” – that is, renounce violence even if they keep their radical notions – or to “deradicalize” – to renounce Salafist or jihadist ideology. But “the logic of deradicalization or disengagement won’t provide any help towards these individuals,” Mr. Brisard says.

The risks of recidivism for terrorists are comparable to those of other criminal offenders, according to research conducted by Mary Beth Altier, a clinical assistant professor at New York University's Center for Global Affairs. The analysis of 87 autobiographical accounts spanning more than 40 terrorist groups indicates 70 percent of individuals whose disengagement from the organization was involuntary returned to violence.

Dr. Altier says it will take intensive interviewing to establish just how radicalized the individuals who lived in the caliphate have become but that it is important to differentiate between ideological conviction and other motivations, such as a need for belonging and purpose, which can be easier to address.

“At the end of the day, they are just people,” she says. “The best possible case scenario is if they can find a way to reintegrate. Once you limit their alternatives for a conventional life, then they are more likely to go back to terrorism.”

From Blue Apron to HelloFresh, how green are meal kits?

As meal kits have soared in popularity, so have concerns about packaging waste. But a new study suggests that focus may overlook larger systemic problems of waste in the food system.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Time is a precious resource for busy parents. So for Kristin Lawrence of Boulder, Colorado, the idea of pre-portioned ingredients for easy-to-follow recipes arriving at her door feels like a windfall. But she stopped recommending meal-kit services to her friends after too many balked at the amount of packaging involved.

Packaging waste is a frequent concern for environmentally minded consumers of meal kits. But the trade-off might not be as stark as it seems.

Packaging is only one part of the equation. Shopping at the grocery store comes with its own environmental costs, including food waste and transport emissions. And when those costs are quantified in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, meal kits suddenly seem a lot greener. In a study published this week, scientists at the University of Michigan found that recipes sourced from a traditional market were associated with about one-third more emissions than the same meal in a delivery kit.

The researchers are quick to say that they’re not advocating for or against the use of meal kits. Instead, the study authors hope their work will prompt consumers to take a more holistic view of their food choices, no matter how they purchase their meals.

From Blue Apron to HelloFresh, how green are meal kits?

Tech entrepreneur Scott Burns and his family lead busy lives. So the idea of meal kits delivered straight to their door in St. Paul, Minnesota, seemed perfect.

But before long, the convenience of the meal kits became overshadowed by a nagging discomfort. All of those pre-portioned ingredients were encased in layers of cardboard and plastic.

“We were really repulsed by the amount of packaging that we would bring out after having these meals,” Mr. Burns says. So the family eventually canceled their subscription. “This massive amount of packaging in our home was not consistent with the values we want to teach [our kids].”

Packaging waste is a frequent concern for environmentally minded consumers of meal kits. Kristin Lawrence of Boulder, Colorado, is an avid user of the service, but stopped recommending it to friends after too many balked at the packaging.

“It’s a trade-off,” she says. “I was willing to sacrifice some of the waste in order to get good quality time with my kids [at the dinner table].”

But the trade-off might not be as stark as it seems.

Packaging is only one part of the equation. Shopping at the grocery store comes with its own environmental costs. And when those costs are quantified in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, meal kits suddenly seem a lot greener. In a study published this week, scientists at the University of Michigan found that recipes sourced from a traditional market were associated with about one-third more emissions than the same meal in a delivery kit.

The researchers are quick to say that they’re not advocating for or against the use of meal kits. Instead, they hope the study offers a new perspective on the choices consumers make around food more generally.

Meal kit companies like HelloFresh, Sun Basket, Blue Apron, and Plated have skyrocketed to popularity in recent years, making this emerging market a $1.5 billion industry.

Senior author Shelie Miller, an associate professor of sustainable systems at the University of Michigan, had heard many meal-kit users express guilt about all of the individual packets and bottles, ice packs, thermal wrapping, and boxes and plastic bags associated with their meal kits. But Professor Miller suspected that there was more to the story than packaging.

Sure enough, “When you look at the much bigger picture beyond just what’s immediately visible to us,” she says, “the meal kits did turn out better.”

To get a full picture of the greenhouse gas emissions, the scientists calculated not just the volume of packaging, but also food waste and varying transportation-related emissions associated with traditionally sourced meals and delivery kits. And for comparison’s sake, they looked at the same meal, ingredient for ingredient.

As meal kit users might expect, the meal kit’s packaging was associated with greater greenhouse gas emissions – one and a half times as much, says study lead author Brent Heard, a doctoral student at the University of Michigan. But the emissions from packaging make up just a small portion of the total footprint for both meals, he says. About 7% of overall meal kit emissions come from packaging, the team calculated, and 4% for the grocery store meals.

So what could possibly counteract that much packaging?

Food waste is a big part of it, the researchers found. Those pre-portioned ingredients may be largely wrapped in plastic, but they’re also usually just the right amount for the recipe so home cooks don’t end up with much excess. Grocery stores also lose a lot of food, largely because of overstocking and eliminating blemished or unappealing items. And the associated emissions with that food loss are higher, too, due to factors like store refrigeration emissions. Transportation was another factor. Meal kits are delivered along a shared route, while trips to the grocery store are individual.

“I had a suspicion for a very long time of exactly that,” says Elena Belavina, associate professor of applied economics at Cornell University, whose own research examines the environmental impact of online retail food. Meal kits eliminate uncertainty around planning and executing meals, thus reducing the amount of food that goes unused.

Food waste is incredibly carbon intensive for two main reasons, says Professor Belavina. First, food production requires a lot of energy, as farmers pump water to their fields, spray fertilizer across them, and then ship the produce hundreds of miles. And that’s just plants. Meat adds a few more steps into that process. So when food goes uneaten, all that energy was for nothing. Furthermore, when food decomposes in a landfill, it releases methane, which is 25 times as potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

Packaging might actually help reduce environmental impacts sometimes, too, says Susan Selke, director of the school of packaging at Michigan State University. She has researched how some packaging can increase the shelf life of perishable food items that might make it more likely that a consumer will get around to eating them before they start to rot.

As a relatively new product, not much outside research has been done on the environmental impacts of meal kits. And the scope of this study is narrow, focusing just on one company – Blue Apron – and a few consumer scenarios. But the study authors hope their work will prompt consumers to take a more holistic view of their food choices no matter how they purchase their meals.

Americans waste almost a pound of food per person each day on average. So there’s a lot that individuals can do to reduce their footprint simply by not overbuying food or letting it go to waste, says Professor Belavina.

For many people, one trip to the grocery store a week may mean buying a bit too much, but it will save them the time and hassle of having to make multiple trips for things they didn’t anticipate needing. But there are little tricks people can apply, she says, like freezing fresh bread, to make it easier to eat everything.

It’s about striking a balance, she says. “We have to deal with the everyday realities of life.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why Arab protesters stay in the street

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For months, the Arab world has carefully watched ongoing protests in two of its own, Algeria and Sudan. The protests have been surprisingly peaceful, inclusive, and persistent. And in early April, the protesters finally won key victories. The military in both countries ousted longtime rulers whose misrule had sparked the street demonstrations.

Yet the protests have only continued because the generals now in charge refuse to cede power to civilians or move quickly to democracy. Instead, like the despots they replaced, they are trying an old trick to show concern for the people: They are making symbolic crackdowns on corruption.

While the crackdowns represent a nominal respect for rule of law, their real intent is widely seen as a tactic to divide protesters or persuade enough of them to go home with a limited victory.

The anti-corruption moves do not fool the protesters. They understand the best tools against corruption are accountability through free elections, transparency in governance, independence of judges, and the kind of equality that includes civilian rule over a military.

Why Arab protesters stay in the street

For months, the Arab world has carefully watched ongoing protests in two of its own, Algeria and Sudan. The protests have been surprisingly peaceful, inclusive, and persistent. And in early April, they finally won key victories. The military in both countries ousted longtime rulers whose misrule had sparked the street demonstrations.

Yet the protests have only continued because the generals now in charge refuse to cede power to civilians or move quickly to democracy. Instead, like the despots they replaced, they are trying an old trick to show concern for the people: They are making symbolic crackdowns on corruption.

In Algeria, military authorities have launched a “Clean Hands” campaign against current and former government officials as well as wealthy businessmen who benefited from the 20-year rule of deposed leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

In Sudan, the ruling Transitional Military Council, fronted by Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah Burhan, has arrested many officials for fraud, including two brothers of Omar al-Bashir, the ousted leader who sits in jail after ruling for 30 years.

While the crackdowns represent a nominal respect for rule of law, their real intent is widely seen as a tactic to divide protesters or persuade enough of them to go home with a limited victory.

The anti-corruption moves do not fool the protesters. They understand the best tools against corruption are accountability through free elections, transparency in governance, independence of judges, and the kind of equality that includes civilian rule over a military.

“We demand reform of the judiciary until justice prevails and corruption is prosecuted,” said Appeals Judge Abu al-Fattah Mohammad Othman, one of the many judges who have joined the protesters in Sudan. “We demand the removal of symbols of the former regime from the judiciary and the dismissal of the head of the judiciary to achieve justice.”

Despots are able to stay in power by doling out state assets to loyal followers. In Sudan under Mr. Bashir, an estimated 65% of government spending had gone to the military. The question remains whether this same military wants to keep the money flowing by clinging to power.

Democracies, of course, are hardly immune from corruption or the use of patronage. But autocratic states tend to be more corrupt because, by their nature, they rely on inequality and dishonesty. They put rule by person or party above rule of law.

The protesters in Sudan and Algeria have absorbed many lessons from the largely failed Arab Spring of eight years ago. One is not to settle for half-measures from rulers, such as promises to fight the private use of public goods among the elite. Only democracy itself, with its reliance on honesty, openness, respect, and other civic values, can genuinely root out problems like corruption.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A humble and earnest response to the demand for church

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Kim Crooks Korinek

Despite a decline in churchgoing in many countries, people yearn for fresh ways in which to express and share their spirituality. Today’s contributor explores how a rethink of church as founded on the basis of spiritual healing can meet that need and be a powerful force for good in the world.

A humble and earnest response to the demand for church

The demand for church is real. Some might agree with that statement. Others emphatically won’t. And yet in spite of declining membership, concerns about youth leaving church, and tragic stories of abuse, there is something else going on. Traditional forms of religious authority are falling away, giving an opening to a radical reexamination and rebirth of church. An article in today’s Monitor Daily, for instance, speaks to a rise in unconventional outlets for faith and spirituality, such as music festivals.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, shared the following insight over 100 years ago in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “The time for thinkers has come. Truth, independent of doctrines and time-honored systems, knocks at the portal of humanity” (p. vii).

The desire for something new is being pushed by the demand for something higher and holier and is growing to be a driving force. It is a drive that is strong, soundly rejecting hollow traditions for a more practical spirituality. And this is bringing new forms to fulfill the ideals of meaning, healing, and community that are central to a thriving church.

Mary Baker Eddy recognized this deep yearning in humanity and wrote: “This age is reaching out towards the perfect Principle of things; is pushing towards perfection in art, invention, and manufacture. Why, then, should religion be stereotyped, and we not obtain a more perfect and practical Christianity?” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 232).

Dropping all stereotypes of religion as exclusive, blindly dogmatic, or divisive, we find we have a keen opportunity to look with fresh receptivity at the church set out by Christ Jesus, rooted in primitive, practical Christianity – founded on the basis of spiritual healing. Jesus expected his followers to walk their talk. To forgive. To heal the sick. Jesus’ concise summary of all the commandments was simple: Love God and love one another. He knew that outward ritualized worship or simply going through the motions couldn’t unmake bad behavior or come anywhere near to saving humanity. And in my study and practice of Christian Science, I’ve experienced how it isn’t the outward things that transform us, but an inner desire to know God and a willingness to do the work that spiritual transformation requires. It is the daily deeds of goodness and unselfishness whose accumulated actions reveal church as a dynamic force that helps us demonstrate just how God’s love heals and triumphs over adversity.

There is a two-part definition of church in Science and Health that I have found helpful. The first part explains the spiritual substance of church: “The structure of Truth and Love; whatever rests upon and proceeds from divine Principle.” The definition is broad, yet grounded not in human personality, nor in the wisdom of others, but in a knowledge of God as divine Principle, Love – universal, solid, expansive, enduring.

The second part of this definition sets a standard for the actions of church: “The Church is that institution, which affords proof of its utility and is found elevating the race, rousing the dormant understanding from material beliefs to the apprehension of spiritual ideas and the demonstration of divine Science, thereby casting out devils, or error, and healing the sick” (p. 583).

This sense of church, like a spiritual fitness center, is not just about coming to church, but living church as universal, unifying, and all-inclusive: letting God, divine Love, impel what we think and do. It means demonstrating, in some degree, the power of God that triumphs over sin, disease, and death.

We know if we are “doing church right” by our actions and the results of those actions. We can ask ourselves, are we growing in grace, humility, acceptance, and generosity? Are the results of our efforts, even if in modest ways, “elevating” humanity and rousing our thought to more healing and compassionate, spiritual ideals? These are natural outcomes of understanding our relation to God – not just how we think about God, but reclaiming our real identity as the spiritual expression of God’s goodness, love, and truth. With the high goal of healing and all the transformative good that only church can do, we’ll eagerly want to let go of anything that’s blocking the way to this glorious progress.

Each of us, whatever our background, can make a fresh, new commitment to church, to being new-born of Spirit, God, in our consciousness. Our humble willingness to do that opens the way for how powerfully all can experience church as an all-out loving, responsive, and transformative healing and saving force.

Adapted from an editorial published in the March 11, 2019, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

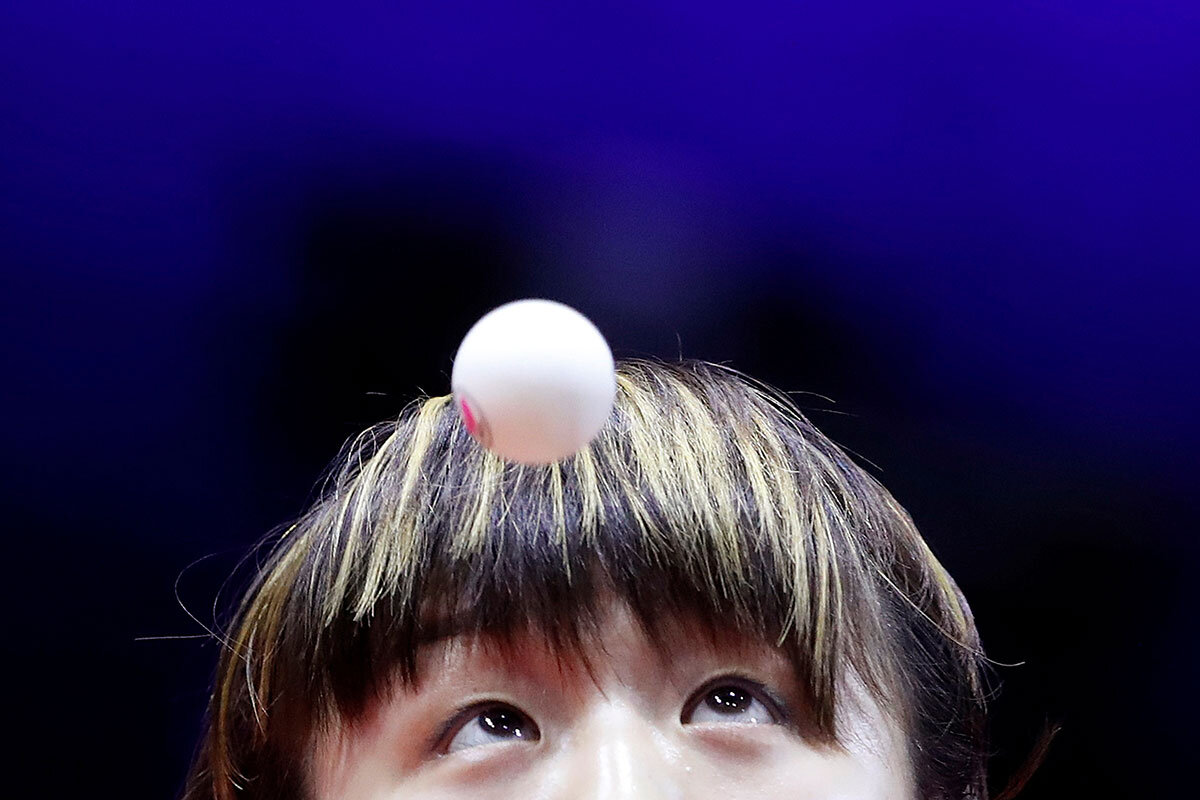

Eye on the ball

A look ahead

Come back Monday, when we’ll have a story about a huge turning point in Japan’s modern history – the first abdication by an emperor in 200 years.