- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why go-for-broke uprising in Venezuela is getting loud US support

- Rebuilding rural America: a post-flood vision emerges in Nebraska

- Art of the steal: European museums wrestle with returning African art

- Seeing Syria through a reporter’s eyes

- From ‘Amazing Grace’ to ‘Diane,’ women shone in April movies

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A step that can change your world view

For all you inventors – and those of you upset by the seeming intransigence of politics – this one’s for you.

Archaeologists say they have discovered the oldest human footprint yet found in the Americas. The print was actually discovered in 2010, at a dig in the city of Osorno, Chile. But it took time to confirm the radiocarbon dating of nearby plant material – and even more time to convince colleagues that such a print was possible. It contradicts the prevailing theory that humans crossed into the Americas from Siberia and didn’t reach Chile until some 3,000 years later.

That theory has been challenged in recent years by geologic evidence and traces of older human activity. Still, peer reviewers were unconvinced by the Chilean footprint.

Maybe the radiocarbon dating was wrong? The researchers checked and rechecked their results. Maybe the find was an animal track that got misshapen to look like a human footprint. The researchers made footprint tests using real people.

Finally, the reviewers agreed with the researchers. Last week, the scientific journal PLOS-ONE published the results: An adult male made the print some 15,600 years ago.

The big question now is: How did he get there? It will take a lot more research to figure that out.

The point is: People eventually abandon outdated theories and begin to embrace new ones as the evidence accumulates. It just takes a lot of patience – and one bold human step.

Now, onto today’s five stories, which include a look at why Venezuela’s coup is happening now, intriguing ideas to rebuild rural America, and Peter Rainer’s picks for best April movies.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why go-for-broke uprising in Venezuela is getting loud US support

The Monroe Doctrine, the 19th-century U.S. policy declaring “hands off!” to other powers in Western Hemisphere affairs, is seeing new life in the Trump administration. But is it a stand for democracy, or U.S. hegemony over its “backyard?”

Announcing the “final phase” of what he dubbed Operation Liberty, Juan Guaidó called on Venezuelans to rise up en masse to join him and the military, which he aimed to demonstrate is now on his side, in wresting power from the Maduro regime.

But despite clashes between opposing groups on the streets of the capital, Caracas, it did not appear that large segments of the military were jumping to support the opposition. Another key element is the degree of U.S. support for Mr. Guaidó’s bold move – and whether or not it remains rhetorical and diplomatic.

The proactive U.S. support for a democratic transition in Venezuela is something of an anomaly for an administration that otherwise has downplayed democracy while praising authoritarian rulers as promoters of stability. But the administration has carved out an exception in the case of Latin America, insisting that democratic rule (and not socialist governance) is the regional standard the U.S. will promote and defend.

What is clear is that this time is different. If Mr. Guaidó’s move fails, the entrenched Maduro regime will almost certainly act to snuff out the elements behind what it declared Tuesday a U.S.-backed “coup” attempt.

Why go-for-broke uprising in Venezuela is getting loud US support

In an early morning tweet in support of the boldest attempt yet by Juan Guaidó, Venezuela’s self-declared “legitimate president,” to seize power, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio issued a do-or-die message to the South American country’s beleaguered people.

“Do not allow this moment to slip away,” he admonished. “It may not come again.”

The Republican senator, who has been a fervent instigator of and cheerleader for the Trump administration’s monthslong campaign to replace the socialist government of President Nicolás Maduro with Mr. Guaidó, may very well be right.

Ever since Mr. Guaidó declared himself interim president in January, the youthful opposition leader has been campaigning for Venezuela’s traumatized population to join him in taking their country back from Mr. Maduro’s failing and increasingly authoritarian governance.

But his video statement from a Caracas military base early Tuesday morning, with uniformed soldiers (and significantly, prominent opposition leader Leopoldo López, who was supposed to be under house arrest) at his side, had the feel of a go-for-broke stand.

Vice President Mike Pence, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and President Donald Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, were all quick to hail Mr. Guaidó’s action Tuesday and to reaffirm U.S. support for the opposition’s efforts to topple President Maduro.

“Democracy will not be defeated!” Secretary Pompeo tweeted.

The proactive U.S. support for a democratic transition in Venezuela is something of an anomaly for an administration that otherwise has downplayed democracy promotion while praising authoritarian rulers in the Middle East and elsewhere as promoters of stability.

But the administration, led by Mr. Bolton, has carved out an exception in the case of Latin America, insisting that democratic rule (and not socialist governance) is the regional standard the United States will promote and defend.

In comments to the White House press Tuesday afternoon, Mr. Bolton described the day’s events as a potentially decisive moment in “the effort of the Venezuelan people to regain their freedom.”

In addition, he called on senior officials within the Maduro government, including the defense minister, to act “this afternoon or this evening to bring other military forces to the side of the interim president.”

Big power competition

Some international relations experts see not so much a firm stand for democracy in the U.S. sanctions and other actions targeting the Maduro government as they do evidence of resurgent big-power competition across the globe.

In that scenario, the U.S. is claiming its hegemony over its “backyard” in much the same way Russia is moving to reassert its influence and control over adjacent, former Soviet republics such as Ukraine.

On Tuesday the Russian Foreign Ministry condemned Mr. Guaidó and opposition forces for attempting to “incite conflict.”

In his morning announcement of the “final phase” of what he has dubbed “Operation Liberty,” Mr. Guaidó called on Venezuelans to rise up en masse beginning Wednesday to join him and the military, which he was aiming to demonstrate is now on his side, in wresting power from the Maduro regime.

But despite clashes between opposing groups on the streets of the capital, Caracas, in which dozens of people were reported hurt, and dramatic footage of confrontations and wafting tear gas, it did not appear that large segments of the military – since the beginning the key to resolution of the Maduro-Guaidó standoff – were jumping to the opposition’s side.

“The symbolism of those uniformed members of the military flanking Guaidó as he spoke is important, not least for the measure of hope it gives the supporters of the democratic transition the opposition is working toward,” says Paula Garcia Tufro, deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center in Washington.

“But my realistic appraisal is that we’re still not seeing enough of the highest ranks of the military abandon the Maduro regime to say the weight has shifted,” she says. “A big part of the calculus” going on within the military “is at what point do they believe the democratic transition will be sustained,” she adds, “and we may get a better idea of that in the coming days” of national protests.

Repercussions for ‘coup’

What is clear, however, is that this time is different. If Mr. Guaidó’s move fails, the entrenched Maduro regime will almost certainly act to snuff out the elements behind what it declared Tuesday is a U.S.-backed “coup” attempt.

A campaign would likely be launched to cleanse the military of elements siding with Mr. Guaidó, regional experts say. Additional repressive measures could be taken against opposition forces – including potentially Mr. Guaidó – they add, although the government would likely avoid turning Mr. Guaidó into a martyr.

“We’re going to see a continued purging of the military institution in the aftermath of this stand by Guaidó, and if anything it’s likely to be stepped up,” says Brian Fonseca, director of Florida International University’s Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy in Miami.

“What I don’t expect to see is the Maduro government coming down hard on Guaidó. I think they understand it wouldn’t be in their interest. If Guaidó falls flat,” he adds, “he will already be showing his weakness.”

The key to the turn of events over the coming days will be “the level of the depth of the military backing of today’s action by Guaidó,” says Professor Fonseca, an expert in Venezuela’s military.

“If Guaidó is unable to demonstrate he’s marshalling the forces he came out today and declared he has behind him, both he and the opposition movement are going to be demonstrating more than anything else that they lack credibility,” he says. “And so far there’s no real indication of the degree of fracturing in the military institution that Guaidó seemed to be claiming there is.”

Ms. Garcia Tufro agrees that Mr. Maduro may not move immediately against Mr. Guaidó, but she says at some point “the Maduro regime will cease allowing him the freedom of movement he has had until now.”

What worries her more in the short term, she adds, is the risk of increasingly harsh repression by the Maduro government of protesters and deserting military elements and “mass arrests.” Noting the large number of small arms in Venezuela and the number of armed irregular defense groups, she says the potential for “deterioration of security” across Venezuela is growing.

Nature of US support

Another key element is likely to be the degree of U.S. support for Mr. Guaidó’s bold move – and whether or not it remains rhetorical and diplomatic, in the form of economic sanctions and coordination with Venezuela’s South American neighbors.

This month Mr. Bolton declared that the Monroe Doctrine is “alive and well,” referring to the 19th-century U.S. policy declaring “hands off!” to other powers intervening in the Western Hemisphere’s affairs. Over recent decades the doctrine took on a pejorative image of Yankee imperialism, but Mr. Bolton appeared to be promoting a revised vision of the doctrine as a regional pact of democratic governance.

“The twilight of socialism has arrived in our hemisphere,” he proclaimed.

Mr. Bolton’s declaration met with stiff criticism from Russia, which scoffed at a revived Monroe Doctrine as a throwback and insisted that Russia and other global actors will continue to engage at will with Latin American countries.

Rebuilding rural America: a post-flood vision emerges in Nebraska

When improving America’s infrastructure comes up – as is happening now in Washington – it often conjures images of wider urban highways. But some of the biggest needs may actually be in rural America.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

After seeing his city saved from recent floods thanks to levees built more than 50 years ago, Josh Moenning is taking a cue. The mayor of Norfolk, Nebraska, says, “Let’s not just rebuild and replace, let’s rethink and reposition how rural Nebraska interfaces with the new economy.”

U.S. infrastructure needs are already on the radar at the federal level – the subject of a meeting Tuesday between President Donald Trump and Democratic leaders. And investment has boosted rural areas before, such as when land-grant colleges in the 1800s spurred farm productivity. But many counties in “flyover America” today are struggling to retain people and job opportunities.

Mayor Moenning wants better internet service, wider and safer roads, and new safeguards against extreme weather. His agenda meshes with that of a coalition called Rebuild Rural, representing rural businesses, farmers, and communities.

“I’m old enough to remember when there was a similar pessimism about our cities,” Tom Barkin, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, wrote in an article on rural economies last year. “The first step in thinking about the problems of distressed rural areas is to approach them as solvable.”

Rebuilding rural America: a post-flood vision emerges in Nebraska

The bridge and river channel in Norfolk, Nebraska, look decidedly ordinary until Mayor Josh Moenning starts to tell his story:

“The water – you see the bottom of the bridge deck? – it was lapping at the deck,” he recalls of last month’s epic flooding here in northeastern Nebraska. The flood control channel “was at almost 90% [capacity] and the north fork of the Elkhorn River upstream was continuing to rise. It had already ravaged communities like Pierce and Osmond and we knew this was real and that we needed to begin evacuations.”

About a third of the city was evacuated. “But in the end, it was this levee system that saved the day for Norfolk,” he adds. “It was that infrastructure investment that was made back in the ’60s to not only build this channel, but to engineer it to withstand and hold so much water, that diverted floodwaters out of the city and saved us from a lot of loss and damage.”

If city leaders had the foresight more than 50 years ago to invest in infrastructure that would save their city from a monster 21st-century storm, shouldn’t Nebraskans today do the same? he asks. “Let’s not just rebuild and replace, let’s rethink and reposition how rural Nebraska interfaces with the new economy.”

It might sound as quaint as an Andy Griffith rerun to suggest rebuilding rural America. In a hyperpartisan era in which Washington is preoccupied with congressional investigations and political posturing for next year’s elections, why would anyone invest in the emptiest portions of flyover states, especially when they’re stuck in what looks like irreversible decline?

But rural America has cheerleaders who are far more optimistic.

“I’m old enough to remember when there was a similar pessimism about our cities, which appeared during the 1970s and 1980s to be doomed to perpetual decline. They weren’t,” wrote Tom Barkin, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, in a bank publication last year looking at the problem. “From my perspective, the first step in thinking about the problems of distressed rural areas is to approach them as solvable.”

Declines in infrastructure and in populations

In Washington, the question of improving the nation’s infrastructure – rural as well as urban – is on the radar for both parties. President Donald Trump’s schedule Tuesday included a meeting on the issue with top Democrats, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer. The two sides have different visions, but it’s an area of potential compromise, in which Mr. Trump’s proposals have included block-grant funding for rural roads.

For rural rebuilding to occur, a mental shift may be needed not just among politicians but rural Americans themselves.

Every year, rural kids go off to college in the cities and suburbs, says John Hansen, president of the Nebraska Farmers Union, a family farm and ranch organization based in Lincoln. “They get good educations and a look at what more cultural, more entertainment, and economic opportunities look like [in the cities]. And a very high percentage of those kids stay and they don’t go back home. And they do that in most cases with the encouragement of their parents.”

Rural America is a complicated mosaic. Some counties are growing because they’re getting the spillover of suburban sprawl. Others are benefiting from the fracking boom or the tourist trade. But in many of its flat, not-so-scenic spaces, rural America is aging and its workers, less educated than their peers in metropolitan areas, struggle because of few jobs and low wages. In 1910, more than half of Americans lived in rural areas; today, it’s fewer than 1 in 5.

In previous times of stress, the United States has invested in rural America with dramatic results. In the midst of the Civil War, the U.S. established land-grant colleges to teach practical agriculture, science, military science, and engineering, which were the basis for today’s state universities and helped make American farmers the most productive in the world.

In the middle of the Great Depression, Congress approved funds for rural electrification. Within a decade, the percentage of farms with electricity jumped from 10% to 40%; by the early 1970s, it was 98%.

A GOP mayor with clean energy vision

Nebraska’s March flooding offers a significant test case. With an estimated $1.4 billion in damage and 81 of its 93 counties eligible for disaster aid, the state is moving to repair its infrastructure. It’s an opportunity Mayor Moenning here in Norfolk doesn’t want to pass up.

“When we fix mangled highways, why not put in place the fiber optics and telecommunications infrastructure that addresses that rural broadband gap that politicians have talked about for so long?” he asks. Instead of fixing the region’s two-lane highways, why not the four-lane corridors that rural Nebraskans were promised decades ago?

Let’s “rebuild electricity transmission infrastructure that helps meet growing market demands for clean energy and accommodates the renewable energy generation potential that the state has in abundance,” he adds. “And I think, finally, when you’re looking at disaster-control infrastructure, why not start planning for what we once considered 100- and 500-year floods to be more like 10- or 15-year floods?”

The mayor, a Republican, doesn’t exactly fit the mold of a red-state politician. He drives a Subaru in pickup country, directs a wind-energy advocacy group, and sports blue shoelaces on his black wingtips. (“I bought them this way,” he explains. “I like to shake things up.”)

But his agenda is very much in line with the investments supported by Rebuild Rural, a coalition of more than 240 groups representing farmers, agricultural cooperatives, and rural businesses, communities, and families. And there is precedent for rural America taking advantage of disaster to rebuild for the 21st century.

After a powerful tornado leveled 95% of Greensburg, Kansas, in 2007, state Gov. Kathleen Sebelius suggested rebuilding it in a sustainable way. “It wasn’t that radical an idea,” says Matt Christenson, Greensburg’s current mayor. “Frankly, a lot of the ideas around sustainability are straightforward. In the long term, they save more money.”

With lots of federal help and funds secured by the Kansas congressional delegation, Greensburg outfitted its new city and county buildings, the hospital, and the school with geothermal heating and cooling. Some have solar panels. Some have green roofs (where drought resistant plants help insulate the buildings). Instead of the expensive old diesel engines that used to run the municipal power plant, the city now buys its energy from a local wind farm. It’s considered one of the greenest small cities in the nation.

“I’m committed to my community,” says Mayor Christenson. “Definitely, rural America faces challenges. But with challenges comes opportunity.”

Trump administration task force

And there are signs that the Trump administration is addressing some of the long-term challenges in a region that strongly supported him in the last presidential election. In April 2017, President Trump established the Interagency Task Force on Agriculture and Rural Prosperity, which has since come up with recommendations around five areas: improving internet connectivity, quality of life, the rural workforce, technology and education, and economic development.

For example: The administration has refocused an Obama-era program of transportation grants onto mostly rural roads and bridges, and away from urban walking, biking, and transit projects. Widening two-way roads to four lanes not only encourages commerce by making it easier and faster for trucks to travel, it also would improve safety. A Congressional Research Service study last year found that the rate of fatal accidents on rural roads was more than double the rate on urban roads.

Another push is high-speed internet, considered essential for 21st-century commerce. Some 6% of Americans (and nearly a quarter of those in rural areas) lack access to fixed broadband service, according to a 2018 Federal Communications Commission report. And although a 2019 draft report suggests progress in rural areas, the estimated gains may be overstated.

The FCC considers Iowa essentially fully served by broadband, for instance. Yet nearly 500,000 speed tests run last year suggest Iowans reach those speeds only 22% of the time, according to The New Food Economy, an online nonprofit newsroom.

Last week, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced it was accepting applications for at least $600 million in grants and loans to increase rural broadband access through a new program. The pilot program more than doubles the USDA money available to companies willing to undertake the time and expense to give rural homes high-speed access.

One set of groups in the mix to do that are rural electric cooperatives, which brought electricity to these same regions some 80 years ago. To take advantage of the new federal money, Mississippi and Georgia have passed legislation to allow cooperatives to accept such funds.

Some efforts to rebuild rural America are bipartisan.

Earlier this month, Sens. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Jerry Moran, R-Kan., introduced a bill authorizing $25 million in grants to help rural electric co-ops develop storage and microgrid projects for renewable energy over the next five years. The effort builds on a federal Department of Energy program that ran from 2013 to 2018, which boosted rural co-ops’ production of solar power more than tenfold.

“Rural complements urban and urban complements rural, and we’re all in this together,” Mayor Moenning says. “The better we understand that, the more we work together [and] the brighter the opportunities will be.”

A deeper look

Art of the steal: European museums wrestle with returning African art

The debate about repatriating African art involves issues that go beyond museum doors: identity, ownership – and coming to terms with the past. What should justice for long-ago looting look like in today’s world?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

-

Ryan Lenora Brown Staff writer

The first time Abdulkerim Oshioke Kadiri visited the British Museum, he was astounded. Mr. Kadiri, the acting director general of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments, had never seen so many Benin bronzes in one place – the famous relief sculptures plundered from present-day Nigeria in 1897 and scattered to museums across the West. “I saw how my people were being appreciated” by the world, he remembers.

But his pride was quickly stifled by another emotion: loss. Most Nigerians, he knew, would never have the resources to stand where he did and look at their own history.

Who should be the caretaker of Africa’s cultural heritage – the Africans who created it or the Europeans in whose museums it has long been displaced? For decades, art experts and politicians have debated the morality and practicality of returning art. But a report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron, which recommended returning art taken during the colonial period, has injected a sense of urgency.

Today, some of the Benin bronzes may be on their way home – temporarily – through a program to return items on loan. But whether that is a road map or a cautionary tale depends on whom you ask.

Art of the steal: European museums wrestle with returning African art

A dozen teenagers in matching burgundy school uniforms crane their necks toward a floor-to-ceiling display inside the National Museum here in Benin City.

“Does anyone know what this is?” asks Abigail Zaks-Ali. The tour guide doesn’t turn around as she begins to explain the photograph behind her. She doesn’t have to. She knows this story by heart.

The photo shows three white men sitting on stools, decked out in the white linen uniform of the 19th-century colonial explorer in Africa. Two have cigarettes dangling cavalierly from their lips. The third, his pith helmet casting a shadow over his face, is beaming. In front of them, scattered like old toys, are dozens of metal relief sculptures. More statues are jumbled behind them in haphazard piles.

“Those are our artifacts you see,” Ms. Zaks-Ali says. “These men took them to London and then sold them for a very low price.” The students nod in recognition. They have grown up with this story: the story of the British soldiers who arrived here in 1897, promising to negotiate; the story of the white men who instead torched the kingdom of Benin and carried away thousands of its precious artworks to pay for their expedition.

“You see how these men are smiling?” Ms. Zaks-Ali asks, finally turning to face the photograph. “They’re proud of what they took from us.”

A continent away, in the British Museum in London, dozens of reliefs like those in the photo are suspended in rows from floor to ceiling. The room is dark, and spotlights illuminate the rust-colored plaques and intricately crafted figures protruding from them. A few people wander through the room. One young woman takes a selfie in front of the reliefs. Few stop to read the text on a panel beside them, which explains how the works were looted. It is titled “The Discovery of Benin Art by the West.”

When a report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron recommended late last year that the French government begin returning African art taken during the colonial period, it injected a sense of urgency into an enduring debate engulfing much of the museum world: Who should be the caretaker of Africa’s cultural heritage – the Africans who created it, or the Europeans in whose museums it has long been displayed?

It’s a debate that has been happening in various forms since the era of African independence five decades ago. And perhaps nowhere has it played out more prominently than in the case of the famous Benin bronzes, plundered in 1897 and eventually scattered to museums and private collections across Europe. More than any other set of artworks, the bronzes made African art visible to Europeans, igniting widespread interest by scholars, artists, and the public. But in Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa, they have also become a kind of shorthand for colonialism’s violent reign – and its lingering influences.

“These bronzes are more than art,” says Ikhuehi Omonkhua, the chief exhibition officer of the National Museum in Benin City. “Keeping them abroad is like holding our ancestors hostage.”

But now, some of the bronzes may be on their way home – temporarily. Since 2010, museum curators from Europe and officials from Nigeria have been working quietly on plans to return the items, on loan, to the city from which they were taken more than a century ago.

The story of the bronzes may be – depending on whom you ask – either a road map or a cautionary tale on what the great former colonial powers should do with their appropriated treasures. It illustrates not only the complicated practical questions raised by repatriation, but deeply moral ones about how societies deal with the violence in their past.

When European explorers arrived at the coast of what is now southwest Nigeria in the 15th century, they found an eager trading partner in the wealthy African Kingdom of Benin. The kingdom (not to be confused with the modern-day country of Benin) was soon trading slaves and goods such as palm oil, rubber, and ivory for guns and other European commodities.

That give-and-take relationship held steady until the late 19th century, when London began pushing to incorporate the territory into the fledgling British Empire. At the time, the kingdom’s oba, a hereditary king, was Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, and his palace was the administrative and religious heart of the monarchy. The kingdom’s highly skilled artisans produced thousands of metal and ivory plaques and sculptures depicting people and events to adorn the palace and for use in ancestral altars. Though the metal pieces are usually referred to as bronzes, they were largely made from brass.

To the British, the oba was a perpetual irritation, obstinately refusing to recognize their flimsy control of the region. And so in December 1896, British Consul General James Robert Phillips led a small expedition to the oba’s palace. The purpose, he claimed, was to talk trade with the monarch. But in reality, he intended to overthrow him. “I have reason to hope that sufficient Ivory may be found in the King’s house to pay the expenses in removing the King from his Stool,” Phillips had written to the British Foreign Office the year before.

Historical accounts of what happened next – and why – differ, but one thing is clear: Soldiers from the Benin Kingdom attacked the British party, killing eight soldiers.

In retaliation, the British stormed the kingdom with thunderous force. In February 1897, their troops burned large swaths of Benin. They forced the oba into exile and shipped much of his wealth – nearly 3,000 brass and ivory figures that had been his personal possessions – to London.

There, some artifacts were given to the British Museum, while hundreds more went up for auction. Of those, some ended up in private hands, but most found their way into museums in Germany and other European countries, as well as the United States.

In Benin, the theft of the bronzes became a symbol of everything Nigerians lost to British colonialism, a story passed from generation to generation like a parable. “We grew up knowing that our people were massacred and our art was stolen,” says Kingsley Inneh, head of the bronze-casters guild in Benin City. “It was something that was lodged in our memories from a very young age.”

Meanwhile, Nigeria had its own museums to think about. In the aftermath of the country’s brutal civil war with the breakaway Republic of Biafra in the 1960s, Nigerian authorities poured money into the development of cultural institutions, hoping they could do something independence had not: unify the country.

“This museum and many others were built to show us that our history was shared,” says Mr. Omonkhua, of the museum in Benin City. But a lot of that history wasn’t there. While the museum in Benin did have a few bronzes, its collection was paltry in comparison to what was on display in Europe. The two largest collections are in the British Museum, which holds around 900 pieces from Benin, and the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, soon to be part of the Humboldt Forum, which possesses around 530 pieces.

And as Nigeria plunged into economic free fall in the late 1980s, its museums became a target for art thieves. The most infamous break-in came in 1994, when robbers stole artifacts worth about $200 million. For curators like Mr. Omonkhua, who had spent their careers evangelizing about the value of museums, the losses were devastating. Even worse, he says, is the way they became a symbol of Nigeria’s carelessness with its own history. If Nigerians couldn’t protect the contents of their museums, the argument went, why should European institutions entrust them with more objects?

The first time Abdulkerim Oshioke Kadiri visited the British Museum, in 2008, the acting director general of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments was astounded. Even though he had toured dozens of museums in Nigeria, he had never seen so many Benin bronzes in one place. “I saw how my people were being appreciated” by the world, he remembers. “I was amazed at how well [the bronzes] were cared for and displayed.”

But his pride was quickly stifled by another emotion: loss. “The naked fact is that these were stolen from us,” he says. “They shouldn’t be here. They didn’t arrive freely.” Most Nigerians, he knew, would never have the resources to stand where he did, in a museum in London, and look at their own history.

Western curators have long deployed a range of arguments to keep it that way: that countries of origin don’t have the museum infrastructure required to keep the artifacts safe, to adequately care for them, or to offer access to the public. That it is not always clear to whom the artifacts should be given – the people they were taken from or the nation-state that exists now? That the public interest served by eminent museums, and how they help people understand the world, outweighs the claims to restitution.

Chris Spring, who was curator of the Africa galleries at the British Museum until last year, says it would be positive to see loans of royal Benin works to Nigeria and possibly returns of certain pieces. “But in this day and age, in this multicultural society, a total repatriation of all those objects would almost be an act of vandalism in its own right,” he says. “It would be depriving so many millions of people of the knowledge of those extraordinary histories.”

For Nicholas Thomas, director and curator of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, the question is a complicated one. In his office at the museum, which holds around 168 objects likely taken during the 1897 expedition, he acknowledges that arguments about conservation can sound like excuses to avoid restitution. “But it isn’t just an excuse,” he says. “There are plenty of cases where, despite the dedication of local museum staff, they don’t have the resources to manage material in the way that they would like.”

The Benin bronzes also illustrate how the ownership of artifacts can get complicated. The reliefs and sculptures were the personal property of the oba when they were stolen – so many might consider his descendant and current oba, Ewuare II, the rightful owner. But because the place they were taken from is now part of the state of Nigeria, the government there also claims them. Neither of the two museums in Europe with the largest collections of Benin bronzes has received an official request for restitution of the objects; one European curator suggested a disagreement over who they belong to could be part of the reason.

Even when returns are requested, the decision in some cases is not up to the museums at all: The British Museum Act of 1963 prohibits an institution from disposing of objects in its collection except in very limited circumstances, meaning any effort to repatriate objects would require government action. Similarly, French law considers the collections of national museums “inalienable,” prohibiting their removal. Other museums and countries have different legal frameworks and processes for dealing with their treasures.

To Jürgen Zimmerer, a history professor at the University of Hamburg who studies colonialism, all of these concerns are irrelevant, because the issue is not a practical one but a moral one. “The question is, do you keep objects which are stolen, or not?” If the answer is no, then there is nothing to do but return them, he says. “The idea that only Europe can keep objects safe is at the core of the colonial ideology, of the colonial gaze. We acquired these museums by looting, subjugating, even killing other people, and it requires a complete decolonization of our museum landscape or our knowledge landscape and people are refusing to do that.”

That means, he says, objects should return home even if the museums they are returning to aren’t as grand as the ones they are leaving behind. The National Museum in Benin City, for instance, has only three small galleries, and they are subject to the whims of a mercurial electrical grid. But the museum’s humble exhibits are carefully tended, and its staff brim excitedly with facts and figures as they shuttle tour groups through the round building.

“It’s a paradox, isn’t it?” says Mr. Omonkhua. “They don’t see us as intelligent enough to take care of our own history. They said we were monkeys, that we were not smart enough, and yet they valued the art produced by these monkeys and put it in their best museums.”

In 2007, Barbara Plankensteiner, then the curator of the Weltmuseum Wien, the museum of ethnology in Vienna, organized a monumental exhibition on the Kingdom of Benin that brought together hundreds of stunning artifacts. Three years later, she facilitated a dialogue with the goal of finding a way to make those treasures accessible to people in Nigeria, as well.

The effort, which became known as the Benin Dialogue Group, brought curators of European museums that hold collections of Benin works together with members of the Benin royal court, Nigerian museum curators, Nigerian government officials, and officials of Nigeria’s Edo State. From the outset, it was clear the group would not address the ownership of the bronzes. Instead, it would seek to bring them back to Nigeria through loans.

The progress was slow. By 2015, participating museums had still not signed a “memorandum of understanding” introduced two years earlier. Finally, last year, the group settled on a solution that managed to overcome the myriad hurdles: It announced plans to build a new museum in Benin City and fill it with some of the most iconic artifacts from the Benin Kingdom, from both European and Nigerian museums.

The Benin Royal Museum will be developed by Edo State and the royal court, with the support of the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments. European museums have pledged to contribute artifacts from their collections of Benin bronzes, on a rotating basis. The museum is scheduled to open in 2021.

The decision was celebrated in Europe, with headlines proclaiming the return of the looted treasures. But to some Nigerians, it felt a little like a slap in the face. “You can’t loan someone something that you stole,” says Emmanuel Inneh, a bronze caster in Benin City.

Officials are more circumspect. “We are anxious that our people should have access to their history in whatever way,” says Prince Gregory Akenzua, a member of the royal court and dialogue group. “We haven’t surrendered our demand for restitution. But we will participate in any effort to make these objects available to our people.”

Others see getting the art on loan as better than having nothing in their display cases at all. “You have to be realistic,” says Folarin Shyllon, a professor of law at the University of Ibadan and a member of the dialogue group. “Half a loaf,” he says, “is better than no loaf at all.”

European curators view the loans as the beginning, not the end. “I think we all understand in the group that it’s a minimum, and it’s a first step,” says Jonathan Fine, curator for the collections from West Africa at the Ethnological Museum in Berlin and a dialogue participant.

Just a few months after the group’s announcement, developments in France undermined the idea that loaning looted art back to the countries it was stolen from was an appropriate way to deal with the past. After declaring in 2017 that he wanted to see the “temporary or definitive restitution of African cultural heritage to Africa,” President Macron commissioned a report to plot a road map for doing so. In December the authors, Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr and French historian Bénédicte Savoy, recommended that France immediately begin repatriating objects obtained without consent during colonial rule, if countries ask for them back. They dismissed the idea of long-term loans. Perhaps most shockingly, they proposed turning around the burden of proof: Instead of demanding countries prove the objects were stolen, France should have to prove they were not stolen if it wants to keep them, they said.

That pushes the debate into radical new territory. While it is widely acknowledged that the Benin bronzes were looted, there is disagreement or uncertainty over thousands of other objects in European museums. Professor Zimmerer, who is a member of a committee coming up with new guidelines for German museums, says the change is necessary. “A colonial context is a context of injustice,” he says. The imbalance of power, he notes, was so pervasive that even transactions that seemed fair may not have been. “Not every object is stolen, not every object is acquired illegally, but the assumption is that a majority of them are, and this should be the starting point of our deliberations.”

Curators reject the idea that most of the objects in their museums were acquired unfairly. “The debate has unfortunately generated a sense that these collections are really only about one thing and that is colonial appropriation,” says Mr. Thomas. “Whereas I think the collections have incredibly complex stories, and there is a lot of the material that reached museums in Europe through local agency, through indigenous agency.” He cites as examples objects that were diplomatic gifts or the “historical equivalents of today’s tourist souvenirs.” And he says that contrary to widespread perceptions, many museum curators do want to grapple with colonial history and work toward collaborative solutions.

No one expects the French report to lead to the emptying out of museums across Europe. Even those who advocate restitution don’t want to see all African art returned. Professor Zimmerer points out that many museums could return large numbers of artifacts without even affecting their galleries: The British Museum displays just over 100 of the 900 Benin objects it has. The Berlin Ethnological Museum displays about 50 percent of its Benin artifacts.

In the meantime, people in Benin City are hardly waiting around for their history to be returned. Down the road from the oba’s palace, wedged between mechanics’ garages, dental clinics, and used clothing stores, are the workshops of the city’s current generation of bronze casters. More than 100 men work along this narrow stretch of Igun Street, meticulously casting and recasting scenes from Benin’s history. It is a process that has changed little over the centuries.

“We are the journalists of Benin,” says Mr. Inneh, the head of the bronze-casters guild, a hereditary organization that has long been the only supplier of statues to the monarchy here. “Before writing, this was the way we recorded events.” Important people and events in the history of the kingdom are cast again and again, as a way of preserving history.

“All we are saying is that these are ours,” says Mr. Inneh. “They were taken by force and now we want them back.”

Reporter’s notebook

Seeing Syria through a reporter’s eyes

With Islamic State forces at last dislodged from Syria, Monitor reporter Dominique Soguel returned to the region, finding a people and a nation mired in contrasts.

I first visited Syria as a reporter in 2008, focused at the time on Iraqi refugees. It was hard to imagine then that a country with such a rich history of hospitality would end up with half its population displaced, within and beyond its borders. A police state, it was never an easy country in which to practice journalism, but the warmth of its people and diverse cultures made it an incredible country to live in, which I did for nearly two years. But for years, owing to my editors’ security concerns, I kept tabs on Syria from its borders.

Returning in March marked a far longer gap than I would have liked. From Iraq, I crossed into northeast Syria, where Kurds have secured a measure of autonomy and security. On the drive to Qamishli, I was struck by the contrast between neglected, shredded roads and the smooth operation of oil pumps. I learned that my driver, Ibrahim, had found asylum in Germany, but returned to his homeland convinced that the gains made during the conflict would survive all the geopolitical wrangling. That same optimism drives children to learn Kurdish music and adults to take on Kurdish literature.

I heard a range of perspectives: Arabs who lived under the Islamic State and reject the group, others who embraced it; Yazidi survivors and Christians; Kurds aligned with the United States, and those who trust Russia more; Syrians convinced that a political solution to the conflict must be found in Damascus, and others who say neither security nor peace are possible as long as President Bashar al-Assad is in power. – Dominique Soguel

Gains, and losses, in Syria

From ‘Amazing Grace’ to ‘Diane,’ women shone in April movies

Among April’s highlights, Monitor film critic Peter Rainer highlights “one of the greatest concert documentaries ever made,” featuring Aretha Franklin at the height of her powers. Of “Amazing Grace,” he writes, “It reaches so far into transcendence that watching it becomes an almost ecstatic experience.”

-

By Peter Rainer Film critic

From ‘Amazing Grace’ to ‘Diane,’ women shone in April movies

Monitor critic Peter Rainer found that the best films in April all featured women in leading roles. Here are the ones that impressed him the most.

In ‘Amazing Grace,’ Aretha Franklin soars to the heights

“Amazing Grace,” featuring Aretha Franklin at the height of her powers, is one of the greatest concert documentaries ever made. It reaches so far into transcendence that watching it becomes an almost ecstatic experience.

And yet the film almost didn’t get released. Some brief background: Shot in 1972 over a period of two days in the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in South Los Angeles, it features Franklin, backed by the Southern California Community Choir and the Rev. James Cleveland, recording a live gospel album before an audience mostly made up of parishioners. The album, “Amazing Grace,” went on to become the most popular gospel album of all time, but the movie, for technical and legal reasons, only lately emerged from limbo.

Franklin, whose father was the legendary Baptist minister C.L. Franklin, grew up in the church, and the album, coming at a time when she had recorded 11 No. 1 rhythm and blues hits in the previous five years, with five Grammy wins, was an attempt to return to her roots. As the film testifies, she never really left them. Her voice is a balm of sanctity. We don’t see the rehearsals that preceded the filming, but there’s a moment in the documentary when she suddenly stops and asks for a second take. I heard absolutely nothing wrong with the first take, but I was reminded of Fred Astaire, who reportedly would look at the footage of one of his dance numbers and ask that five frames be trimmed. And he would be right.

It’s tempting to view “Amazing Grace” as a time capsule of the ’70s civil rights era, but that designation seems insufficient in the face of such immediacy. I have only one regret. Elliott has described how he reluctantly cut Franklin’s rendition of “God Will Take Care of You” from the film, and surely, with 20 hours of footage to work with, there must have been other sacrifices. If ever a film deserved an expanded director’s cut on DVD, “Amazing Grace” is it. Grade: A (Rated G.)

‘Diane’ is a quiet pleasure

Mary Kay Place has quietly and resolutely been doing sterling work in the movies and television since her “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman” days, but “Diane,” in which she plays a widow in rural Massachusetts, is perhaps the first time she has had a full-scale role that is worthy of her. She plays a woman whose life is bound up in sacrificial service to others. Diane is a bit like a New England version of a character in a Chekhov or Sholom Aleichem story – a holy sufferer.

She endures much sorrow, including a drug-addicted son (Jake Lacy) and the slow fade of her dying cousin (Deidre O’Connell), but she is sustained throughout by what can perhaps be best described as a dogged state of grace.

The film was written and directed by Kent Jones, a noted documentarian (“Hitchcock/Truffaut”), film critic and director of the New York Film Festival, making his dramatic film debut. He has a fine way with his cast, which also includes such stalwarts as Estelle Parsons, Joyce Van Patten, Phyllis Somerville, and, best of all, Andrea Martin (who is not in the film enough). Despite his extensive cinema literacy, I never felt l was watching a pastiche of other filmmakers’ movies.

There are some deficiencies. The narrative is set up so that the lead characters expire one by one, which can make for some pretty dreary longeurs, and the scenes with the son don’t share the lived-in verity of Diane’s scenes with her friends and family. But it’s a rarity, and a real pleasure, to find a movie that presents without condescension rural working-class people, especially women. Grade: A- (This film has not been rated.)

‘Working Woman’ brings serious, #MeToo lens to office stories

Movies about beleaguered women in the workplace have generally been spoofs, like “9 to 5,” or feature tyrannical female bosses, like “Working Girl” or “The Devil Wears Prada.” The distinction of “Working Woman” – which was directed by Michal Aviad from a script she co-wrote with Sharon Azulay Eyal and Michal Vinik – is that it doesn’t gussy up, or melodramatize, the story. It’s a steadfast piece of work, shot mostly in long, hand-held takes, and this approach reinforces the inescapability of the protagonist’s plight. In some ways, “Working Woman” is a species of horror film.

Orna (Liron Ben-Shlush) is the mother of three children and wife to Ofer (Oshri Cohen), who is struggling to manage his new restaurant in Tel Aviv, Israel. To earn vital money for the family, Orna takes a job as the assistant to Benny (Menashe Noy), a real estate magnate, who soon makes inappropriate advances, including pushing in for a kiss. Orna’s dazed rejection – she points out that she is married, as is he – is met by his profuse apologies and a promise this will not happen again. Of course, we know otherwise.

Benny, in a fine performance by Noy, is no two-dimensional Hollywood goblin. If he were, it might be easier to dismiss him as an aberration. It is his very humanness that is his most chilling aspect. I wish Ben-Shlush, who somewhat resembles an Israeli Juliette Binoche, were a bit more expressive in the part of Orna. And the film’s narrative is too diagrammatic; all the accusatory pieces fit too neatly into place. Because what came before is so starkly believable, the film’s quick fix denouement diminishes both the severity of what we have been witnessing and what surely must follow.

Still, this is one of the few films about sexual harassment in the workplace that has the feel of authenticity. With quiet, incremental force, it brings home the helplessness and terrors of being trapped. Grade: B+ (Not rated. In Hebrew, French, and English, with subtitles.)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

How gratitude can ease Japan-South Korea frictions

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

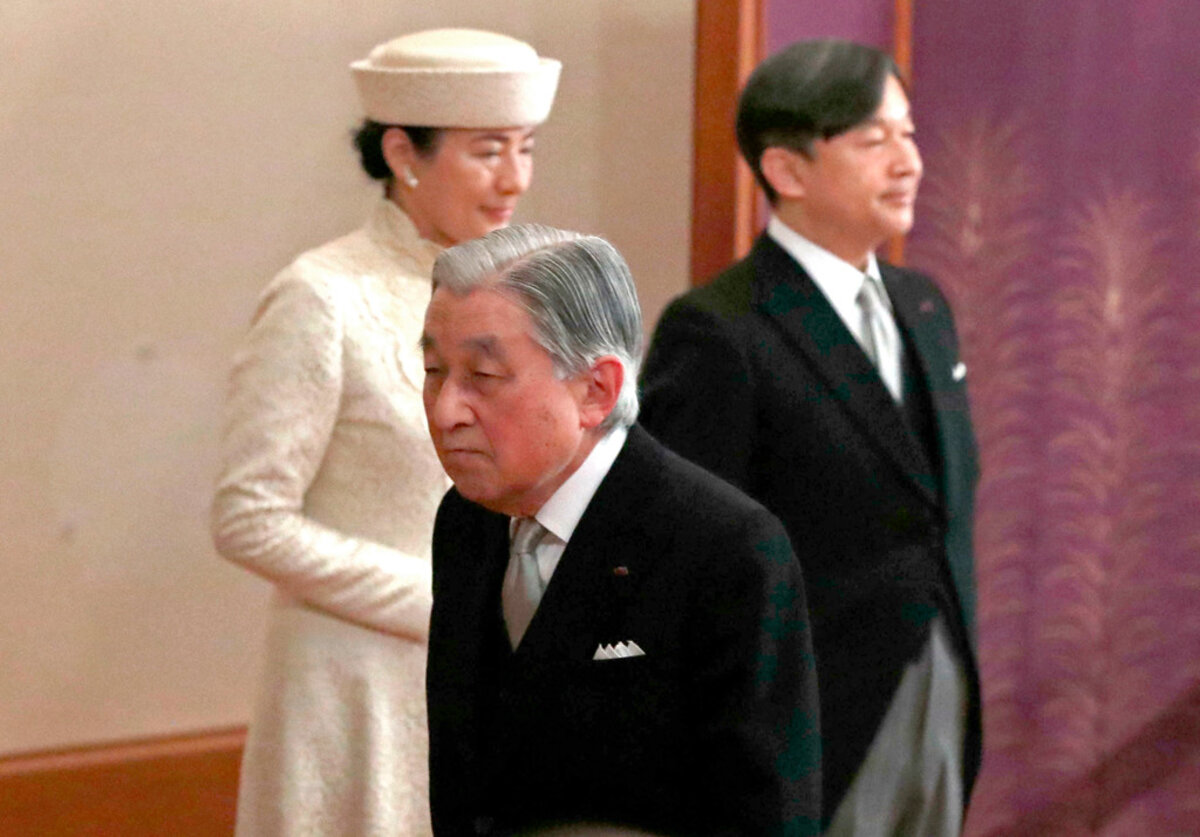

It is a welcome surprise that South Korean President Moon Jae-in has sent a letter to Japanese Emperor Akihito, who retired from the throne April 30. He expressed gratitude for the outgoing emperor’s role in improving ties between Seoul and Tokyo. Mr. Moon also said his government might send a delegation for the coronation of the new emperor, Naruhito.

The South Korean leader is right to be grateful. Akihito played a big role as a peacemaker. After he ascended the world’s oldest monarchy in 1989, Akihito traveled widely to repair relations with Japan’s adversaries during its wartime period from 1931 to 1945. He expressed remorse for the country’s mistakes and prayed for its victims. His efforts at reconciliation have sometimes been at odds with Japan’s right-wing nationalists who often disregard or reject the country’s past cruelties against other Asian nations.

In diplomacy, expressing gratitude for the good already achieved between two nations can be a lubricant to ease frictions. For anyone, an appreciation for past deeds suggests a humility and openness to reach a consensus, less by willpower and more by listening.

How gratitude can ease Japan-South Korea frictions

Despite two recent summits, ties between Washington and Pyongyang are at a low again. Yet they may not be as low as ties between two American allies also dealing with North Korea. Japan and South Korea are in a major dispute over their shared history, specifically whether Japan should compensate Korean laborers used during Japan’s colonial rule of the peninsula. Their diplomatic spat has the potential to hinder a solution to North Korea’s nuclear threat.

It is a welcome surprise, then, that South Korean President Moon Jae-in has sent a letter to Japanese Emperor Akihito, who retired from the throne April 30. He expressed gratitude for the outgoing emperor’s role in improving ties between Seoul and Tokyo. Mr. Moon also said his government might send a delegation for the coronation of the new emperor, Naruhito, in October.

The South Korean leader is right to be grateful. Akihito played a big role as a peacemaker, and not only with a country that his late father, Hirohito, once ruled with near-divine status. After he ascended the world’s oldest monarchy in 1989, Akihito traveled widely to repair relations with Japan’s adversaries during its wartime period from 1931 to 1945. He expressed remorse for the country’s mistakes and prayed for its victims.

His efforts at reconciliation have sometimes been at odds with Japan’s right-wing nationalists who often disregard or reject the country’s past cruelties against other Asian nations. Even though he served only as a symbol of the state and was barred under the Constitution from a political role, Akihito nonetheless helped soften Japan’s image by his gestures of contrition. Notably in 1990 he spoke of his “deepest regret” for the Japanese occupation of Korea.

His actions may be one reason the people of Japan and South Korea seem to get along much better than their politicians. The two nations share pop culture, and South Korean tourists often visit Japan. Mr. Moon’s letter may be an acknowledgment that it is time for the issue of compensation for Korean wartime workers to be settled.

In diplomacy, expressing gratitude for the good already achieved between two nations can be a lubricant to ease frictions. For anyone, an appreciation for past deeds suggests a humility and openness to reach a consensus, less by willpower and more by listening. British writer G. K. Chesterton called gratitude “the highest form of thought.”

With Mr. Moon soon to meet with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the two countries can now start from a standpoint of gratitude. The departing emperor has paved the way.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Facing fear with Love

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Kim Hedge

When today’s contributor froze with fear on a high ziplining platform, mentally pausing to feel God’s universal, all-encompassing love broke through the fear. Then not only did she participate in the activity; she thoroughly enjoyed it!

Facing fear with Love

I recently watched the trailer for a film about climber Alex Honnold’s free solo climb of El Capitan. While watching, I became so utterly consumed by fear that my stomach was in knots and the palms of my hands started to seriously sweat. I was grateful the trailer was short.

Did I have an actual reason to fear? I was sitting in my study watching a video on my tablet; I was not on the face of a giant cliff. But in that moment, it didn’t seem to matter.

Fear is a funny thing that way; it can seem to completely overtake us. But we actually get to decide each moment and with each experience if we will let fear overpower us. It takes more than willpower, though. So how do we conquer fear?

Last summer I had the opportunity to give this some serious thought when I was working at a camp. The activity one particular morning was ziplining. After a rock climbing accident earlier in my life, I had developed a fear of heights that I had never really challenged. But here I was at camp, where the campers in my group were overcoming fears, pushing their human limits, and challenging themselves every day. One of the campers asked if I was going to participate in this activity. I hadn’t planned to participate, but then a voice came from inside saying “Are you really going to let your fear get the best of you here?” So I decided to try it.

I paired up with one of the boys; we were going to go on the tandem ziplines together. Someone counted down – “Three… two… one… jump!” – and the camper jumped off the platform and started off. I, on the other hand, was still on the platform. I couldn’t seem to make myself do it.

I knew from my study of Christian Science that I did not need to let fear win the day. This isn’t to say that we should ever ignore our fears. Sometimes it might be best to heed them and not push forward, and spiritual insight can lead us to avoid dangerous situations. But it felt clear to me that this was not one of those situations.

There’s an encouraging statement in the Bible that says “Perfect love casts out fear” (I John 4:18, New King James Version). “Perfect love” to me is universal, ever-present, all-absorbing, all-encompassing, spiritual love that comes from God, who is infinite Love itself. It is the kind of love our divine Father-Mother, God, has that says “I am right here embracing you and will never let anything happen to you. I am protecting you. I am upholding you and carrying you. All you have to do to feel My love and care is open your heart to Me.”

Fear really stems from thinking we’re subject to some power other than God, good. And when we realize that as God’s children – the spiritual expressions of God’s limitless love – we are always safe and cared for, we find renewed strength to challenge fear as fundamentally powerless in our lives. Mentally pausing to listen and allow our thoughts to be at one with divine Love helps us find inspiration that guides us to safety and brings comfort, confidence, and peace.

So in this case, I thought about the love and joy I felt when I saw the campers facing down their fears and pushing the limits of what they thought they could accomplish. And the sheer joy of the camper who jumped off that platform and whizzed down the zipline ahead of me. It’s natural for all of us to feel love and joy. It’s how God made us.

And then, there we went again: Three… two… one… jump! And I went! And I loved it. It was so much fun that on the next leg of the zipline, I actually raced the camper (who had kindly waited for me at the next platform).

Understanding and feeling God’s love has helped me overcome both small and larger fears. I have also experienced how identifying and overcoming fear in this way is a key element in the practice of Christian Science healing. Moment by moment, we can choose to recognize that we actually live in God, in the consciousness of divine Love, where there is nothing to fear. Divine Love is always here to guide us through all kinds of challenges. As we listen and allow ourselves to feel Love’s ever-presence, God will show us the way to break through fear.

A message of love

Breakfast at the border

A look ahead

That’s all for today. Join us tomorrow when we look at whether the rebuilding of Notre Dame will help bring attention to the other French churches desperately in need of repair.