- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Desperate for change, Venezuelans weigh risks of protest

- Untangling slavery’s roots: the yearslong search for ‘Angela’

- Why Europe is again a battlefield for Iran’s internal wars

- Could aid for Notre Dame help rebuild France’s crumbling history?

- Revenge of the nerd culture: 2019 may mark peak geek chic

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

In Caster Semenya case, a deeper question: What makes an athlete?

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Is it right to require someone to take drugs to compete in international sports? On Wednesday the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport said yes, ruling that the world’s top middle-distance runner, South African Caster Semenya, must suppress her naturally high testosterone levels to run in women’s races.

The court, it must be said, didn’t appear overly pleased with its own decision. It fully admitted that the rule was discriminatory but said the discrimination was necessary to uphold the integrity of women’s events.

The ruling on one hand evoked outrage. “Shouldn’t Semenya’s physical abilities be celebrated the same way as Usain Bolt’s height and Michael Phelps’s wingspan are?” a BBC commentator argued. Yet the ruling is also a natural outgrowth of another trend: the increasing emphasis on biology in elite sports.

If testosterone levels or red-blood-cell counts are the ultimate arbiter of athletic achievement, then the discrimination against Ms. Semenya would seem to have some basis. But is that all there is to sport? Ms. Semenya is also just a woman who loves to run fast and who has become an inspiration in her homeland.

As this case shows, these issues can be difficult and nuanced. But the years ahead point to them becoming only more poignant.

Now for our five stories of the day. We examine how existential fears are changing the behavior of Iran’s regime, a more human look into the first days of slavery in America, and how geeks took over the entertainment world.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

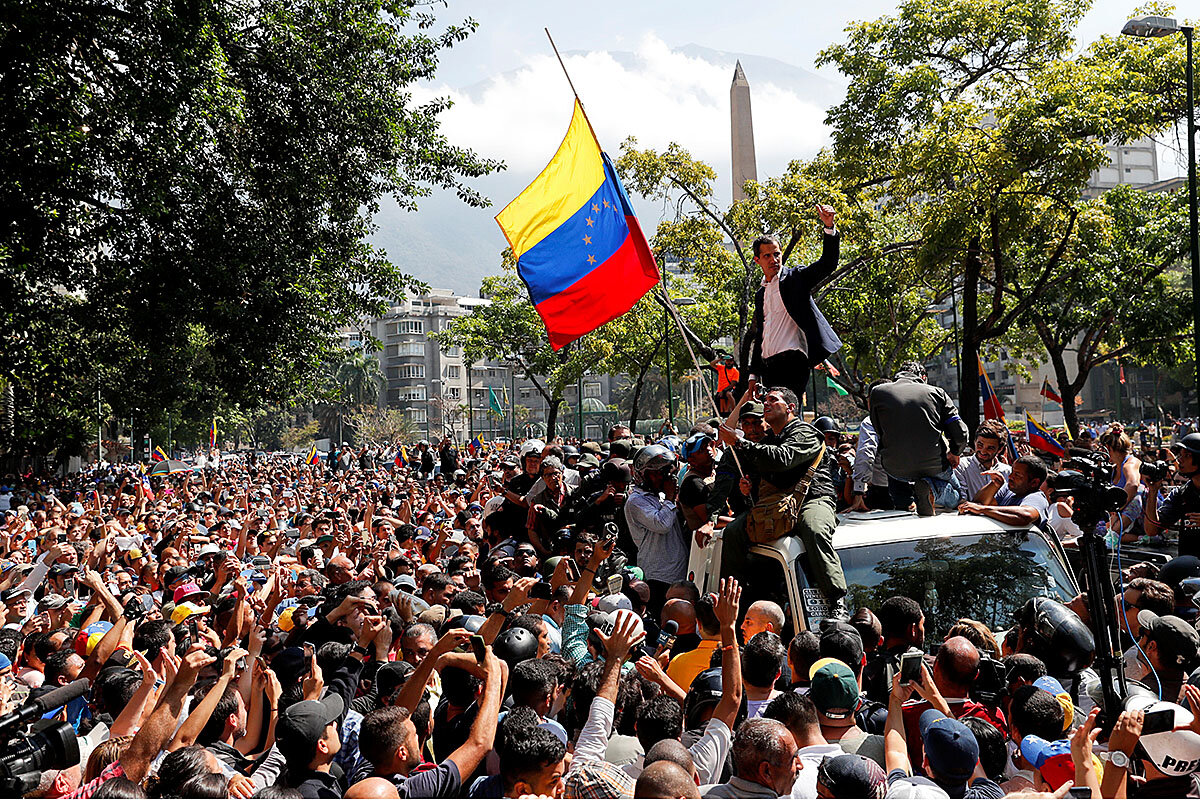

Desperate for change, Venezuelans weigh risks of protest

Opposition protests Tuesday turned to clashes with security, leaving demonstrators in little doubt of the risks if they stay in the streets. But they also are in little doubt of how much their presence matters.

We also want to highlight a few other stories we’ve written on the crisis, which further explain what’s at stake. Please click here to read.

-

By Mariana Zuñiga Correspondent

-

Whitney Eulich Correspondent

On Wednesday, the day Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó urged people to turn out in support of “peaceful rebellion,” Sol Guerra was readying herself for another day on the streets.

“I know they can hurt me or take me prisoner, but I will not stop participating,” says Ms. Guerra. She says that she’s afraid to protest sometimes, but that she’s more afraid of President Nicolás Maduro staying in power than getting hurt.

While much of the focus has been on whether the military will come out to support Mr. Guaidó – no doubt key to success – the presence of thousands of protesting Venezuelans is vital, too. What’s unclear is how much appetite there is among Venezuelans to remain in the streets longer-term, and how much patience they will have with Mr. Guaidó if he’s unable to tip the balance of power in his favor.

The stakes are high. Not only for Mr. Guaidó, who is one of the only people involved in yesterday’s announcement not taking refuge in a foreign embassy. Tuesday’s protests ended with some 60 people injured and a brazen episode of armored government vehicles driving into crowds of protesters.

“If this fails, I will have to leave,” Ms. Guerra says. “But that’s a last resort.”

Desperate for change, Venezuelans weigh risks of protest

The day after a bombshell announcement by Venezuela’s National Assembly President Juan Guaidó that the military was on his side and President Nicolás Maduro needed to step down, the world is still waiting to see how the cards will fall.

Mass defections never came Tuesday. But that hasn’t kept Venezuelans from taking to the streets in a broad show of support for the opposition’s so-called Operation Liberty. By early Wednesday morning, small groups gathering in western Caracas were already facing off with security forces trying to disperse them with shots of tear gas. Across town, thousands of defiant demonstrators dressed in white and wearing tricolor hats of the Venezuelan flag poured into the streets, readying themselves for news of when and where Mr. Guaidó would speak next.

As protesters milled around in the blazing tropical heat in Plaza Altamira, one of 14 meeting spots in the capital, most conversations revolved around what to make of yesterday’s events. Opinions swung drastically between confusion and excitement, with many commenting that they’d expected something more definitive by now. Others preached patience: “Easy, Guaidó knows what he’s doing.”

While much of the focus has been on whether the military will come out to support Mr. Guaidó in larger numbers – key to his plan’s success – keeping thousands of Venezuelans on the street across the country is vital, too. In a YouTube address Tuesday night, he encouraged citizens to show the world where popular support lies, saying “the whole of Venezuela” must hit the streets May 1 to force Mr. Maduro from power in what he called a “peaceful rebellion,” not a coup. The opposition holds that Mr. Maduro’s reelection last year was fraudulent, and that per the Constitution the National Assembly leader is interim president until a new election can be held.

What’s unclear is how much appetite Venezuelans have to remain in the streets longer-term, and how much patience they will have with Mr. Guaidó if he’s unable to tip the balance of power in his favor.

The stakes are incredibly high. Not only for Mr. Guaidó, whose credibility is on the line – and who is one of the only people involved in yesterday’s announcement who has not taken refuge in a foreign embassy – but for Venezuelans demonstrating. Tuesday’s protests ended with some 60 people injured and a brazen episode of armored government vehicles driving into crowds of opposition protesters.

“I know they can hurt me or take me prisoner, but I will not stop participating,” says Sol Guerra, standing in line at a bakery in eastern Caracas Wednesday morning, readying herself for another day on the streets. She says that she’s afraid to protest sometimes, and her mother certainly discourages her out of concern for her safety, but that she’s more afraid of Mr. Maduro staying in power indefinitely than getting hurt.

“If this fails, I will have to leave,” Ms. Guerra says. “But that’s a last resort.”

‘We don’t want to live like this anymore’

Compared to past uprisings, “almost everything is different” this week, says Luz Mely Reyes, director and co-founder of independent Venezuelan news site Efecto Cocuyo. She’s covered every coup attempt in Venezuela since 1992, she says, and “citizen participation is at the heart” of what’s new this time.

In 1992, followers of Hugo Chávez attempted two separate coups. Then in 2002, four years after he was elected president, a coup attempt against him took advantage of existing popular protests, but was orchestrated by a small group without strong public backing.

“In today’s case, what’s important and unique is that people are still in the streets. They’re constantly in the streets” showing their support for change, Ms. Reyes says.

There’s immense hope among opposition supporters, in and outside the country. If Mr. Maduro indeed steps down, it would be the end of the two decades-long Bolivarian Revolution, and could help lay a foundation to pull Venezuela out of a deep economic spiral that’s caused widespread food and medicine shortages, as well as regular blackouts. But the young interim leader’s credibility is at stake: Can he maintain support if there’s no follow through on his lofty declaration?

“We have to show the world that we don’t want to live like this anymore,” says Yajaira Gallardo, a homemaker dressed in a white T-shirt to symbolize peace, on why turning out is key. “I think Venezuelans have been very passive.”

Another key difference between this rebellion and past coups is the level of international support for Venezuela’s opposition – both from Venezuelans living abroad and from foreign governments. More than 50 nations, including the United States, now recognize Mr. Guaidó as the country’s interim president, and expatriates have been instrumental in helping maintain the opposition’s momentum.

“Levels of domestic support, whether expressed through being able to get people to the streets or polls – they’re important,” says Alejandro Velasco, an associate professor of Latin American history from Venezuela who teaches at New York University. “But they’re not decisive. What’s important for momentum is showing the expat [and international] population that you can actually deliver on the promises you’ve been making.”

If the current plan “doesn’t work, we’ll have to ask for more help from Uncle Sam or our neighbors. The government is armed and Venezuelans are not. Alone we can’t make it. My compatriots need to continue in the streets,” says Ms. Gallardo.

The big what-if

But many question if it will be enough – especially if Mr. Guaidó’s bid fails, and the military can’t be swayed. The lack of a clear offer of enforceable amnesty for military leaders if they do defect may be holding some back. Even amid citizens desperate for change, not everyone is willing to risk public protest.

“The reality is I don’t even like to leave the house when there are protests,” says Rovin Pan, a publicist whose best friend’s child suffered severe burns and nearly died in the 2014 anti-government demonstrations. “I put everything in God’s hands. I think all Venezuelans see in Guaidó a new hope,” he says, adding that he contributes in other ways, like sharing information on social media. “In that way I will continue being part of the citizens that want change.”

If Mr. Guaidó fails to deliver on his promises this week, and support for him fizzles, Mr. Velasco agrees Venezuelans will find someone else to peg their hopes to. “In 20 years there have been so many leaders that have come and gone that the hope is always there that ‘This one might be the one,’” he says.

But the very real consequences of failure include even stronger international sanctions against Venezuela, which could directly affect citizens. He expects to see more people flee the country, whether due to a more violent government clamp-down on citizens or simply the loss of hope for a peaceful transition to democracy.

“There will be someone else and people will rally behind him,” he says of opposition leadership. “But the question is, how many people will be left?”

Untangling slavery’s roots: the yearslong search for ‘Angela’

Slavery tries to dehumanize, even in history. Four hundred years ago, the first African was sold into slavery in the American colonies. Research has already revealed an amazing story. It’s just the beginning.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When an Angolan woman known as Angela was sold to Capt. Bill Pierce 400 years ago at Jamestown, it marked a seminal moment: the beginning of chattel slavery in the 13 colonies. It came just weeks after the first general assembly marked the first steps toward democracy.

“It was a symbolic year, to say the least,” says historian James Horn, author of “1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy.”

For two years, archaeologists have been searching for her remains in an effort to bring humanity to some of the first of 12.5 million Africans brought to the Americas to be enslaved. Before even arriving in Virginia, Angela survived war, capture, a forced march, and a harrowing trans-Atlantic voyage in which she and others were captured by pirates. After, she survived slavery, a Powhatan attack that killed hundreds of colonists, and famine. But there the record stops. If they can find her remains, archaeologists say, they can bring her life more vividly to the historical record: How old was she? Did she have children? How did she die?

For Angie Towery-Tomasura, one of the archaeologists, the search for Angela has become a personal mission.

“Her story is written in the dirt,” she says. “We are driven to find it. We want to give Angela a voice.”

Untangling slavery’s roots: the yearslong search for ‘Angela’

Her name, as written down for the first time in a 17th-century muster, was Angelo.

She is now known to history as Angela, one of “20 ... odd” twice-captured Angolans who became the first enslaved people in British North America 400 years ago this summer.

Just behind the fallen Ambler Mansion here on Jamestown Island, a group of archaeologists with T-shirts rolled up to their shoulders are feathering away dust from what appears to be a trash heap – deer bones, broken wine bottles, jar shards. They are searching for evidence of the first African woman to be sold into slavery in the 13 British colonies.

Before arriving in what became Virginia, Angela, whose name also appears in the 1624 and 1625 censuses, survived war, capture, a forced march, and a harrowing trans-Atlantic voyage in which she and others were captured by pirates. After her arrival, she survived slavery, a Powhatan attack that killed hundreds of colonists, and famine. But there the record stops. If they can find her remains, archaeologists say, they can bring her life more vividly to the historical record: How old was she? Did she have children? How did she die?

Overlooking the pit, Jim Horn, the president of Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation and lead historian on the project, acknowledges that little may be found that can be tied directly to Angela. So far, a few beads potentially of African origins have been found.

She is here, somewhere.

Her arrival marked a seminal American moment: the simultaneous beginnings of democracy and chattel slavery in the New World.

“It was a symbolic year, to say the least,” says Mr. Horn, author of “1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy.”

The two-year-long search for Angela on one of America’s oldest historic grounds is intended not just to challenge Eurocentric founding myths, but to bring humanity to the first of the ultimately 12.5 million Africans who were brought to the Americas by 1867.

The digging is also part of a broader reexamination across the United States of a potent mixture of liberty and prejudice, established stateside at Jamestown, that remains a stubborn fixture of American life.

“Through 400 years the questions of slavery and then of race [have] flowed from [Angela’s arrival],” says David Blight, author of this year’s Pulitzer-Prize winning “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.” Just as important, he adds, is the story of the first black people in Jamestown, “these Africans who with time and generations, through slavery and all kinds of migrations, the Americanization process, the Christianization process, and then on into freedom – that’s where their lives here started.

“It was a harbinger of things to come, yet nothing was perfectly inevitable,” says Professor Blight, a historian at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

To be sure, the import of Jamestown on the American experiment is significant, but sometimes overstated.

Trans-Atlantic slavery had been going on for more than 150 years by the time Angela disembarked at Point Comfort, or present-day Hampton, Virginia. And according to Roman Catholic Church records, a black child was born in Spanish St. Augustine, Florida, 13 years before Angela arrived.

“In some ways drilling down too deeply just into 1619 underestimates the transnational horror of what was going on for much longer through the broader Atlantic world,” says Michael Guasco, author of “Slaves and Englishmen.”

“But if we tell the story of 1619 the right way, it’s a way of remembering that the United States at its origins in the early Colonial period is as much African as it is European,” says Professor Guasco, a historian at North Carolina's Davidson College. “[That means] we can look at Jamestown as a starting point – and in some ways not simplifying, but complicating things from that point.”

On Jamestown Island, ospreys screech for attention while oaks whisper in the breeze. A statue of John Smith stands next to the spot where John Rolfe is said to have married Pocahontas. The graves of settlers are marked with thin crosses. The remains of a Civil War fort overlook the James River.

In the public discourse, Jamestown is often framed as a disastrous outing, as opposed to Plymouth, which largely owns America’s origin story. (Next year, the 400th anniversary of Thanksgiving will shift the focus to the Bay State.)

Yet what happened at Jamestown, historians say, cuts close to what America eventually became. The idea, according to instructions from the Virginia Company of London for a first general assembly, was to improve the human condition through locally crafted laws that provided “for happy guiding and governing of the people.” But the company and its colonists had another clear motive (aside from survival): to make profits for shareholders.

“Historians know that when you look at the origins of how something is formed, you don’t go too far from its foundation,” says Cassandra Newby-Alexander, author of “Black America Series: Portsmouth, Virginia.” “We’re in this circle ... where we keep looping back to inequality, keep looping back to racism, keep looping back to unfair treatment, and it’s because we are not looking clearly and honestly at our origins and how those foundations were laid. Four hundred years later, people are realizing it is time to start a new arc.”

Not far from the Angela site archaeologists have uncovered the original Jamestowne Fort and its church, including a choir pew located at “the exact spot where representative government begins only a few weeks before the Africans arrive,” says Historic Jamestowne historian Mark Summers before taking a seat in a newly installed pew.

When Angela arrived, she was purchased by Capt. Bill Pierce. She likely served as a house servant. It is not known whether she married or bore children, although her remains might hold clues to the latter.

What is clear is that the Angolans came as prisoners, not immigrants. In the ensuing years there was little talk about rights for the enslaved. Instead, according to Mr. Horn, the policing of Africans occupied lawmakers.

The year 1619 is the time “freedom stumped its toe ... [at] Jamestown,” as Langston Hughes writes in the poem “American Heartbreak.”

Four hundred years later, on average, black families have only a tenth of the net worth of white families ($17,000 versus $170,000). Disparities in education funding, property wealth, and health outcomes mean that white wealth is growing three times faster than black wealth.

As historians delve deeper into the lives of the first African Americans, “we should not hesitate but to also consider what happens with black family life 400 years later,” says Norfolk State historiographer Colita Fairfax, co-chair of the 1619 Commemorative Commission in Hampton, Virginia. “Why do we see similar and often identical economic situations for black people 400 years later?”

At the same time, historians like Mr. Summers say they are seeing growing interest in understanding the full nature of America’s origins.

In bids to take historical propaganda out of the public sphere, controversial Civil War statues are falling and Confederate flags are being put into museums. Institutions like Georgetown University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and others are acknowledging the role of slavery and racism in their foundations amid questions of why black people on campus are still more likely to be janitors instead of students. The policing of black men especially remains at the forefront of debate over the role of prejudice in policy.

For Angie Towery-Tomasura, one of the archaeologists, the search for Angela has become a personal mission.

“Her story is written in the dirt,” she says. “We are driven to find it. We want to give Angela a voice.”

Why Europe is again a battlefield for Iran’s internal wars

Under pressure from all sides, Iran’s regime feels as if it is fighting for survival. One result appears to be the ramping back up of a long-dormant covert war in Europe.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Last fall, a Norwegian citizen of Iranian descent was found conducting reconnaissance outside the Denmark home of the leader of an Iranian separatist group. “There is sufficient basis to conclude that an Iranian intelligence service has been planning the assassination of an individual living in Denmark,” the country's security service said. Denmark isn’t an isolated case. European officials also accuse Iran of a Paris bomb plot against an opposition rally last year as well as two assassinations in the Netherlands in 2015 and 2017.

Iran denies the charges. But top Iranian officials also say their intelligence agencies have shifted from defensive to offensive operations amid an American campaign imposing ever-tougher sanctions and a renewed covert war with the U.S., Israel, and Saudi Arabia. Iran suspects its enemies of backing ethnic separatists and other regime opponents who have been stepping up attacks inside Iran.

“Right now the Islamic Republic is under huge pressure,” says an Iran expert at the University of Tennessee. “They are thinking about survival, so they have to undermine, they have to kill the enemies ... to create fear among dissidents.”

Why Europe is again a battlefield for Iran’s internal wars

The attack in southwestern Iran last September was the most lethal assault the country had seen in nearly a decade.

On Sept. 22, in the city of Ahvaz, five gunmen opened fire on a military parade commemorating the start of the Iran-Iraq war. Twenty-five soldiers and civilians were killed, among them 12 members of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The desire for revenge was palpable: Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, vowed to “severely punish” those behind the attack, whom he said were paid by arch-foes Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

One claim of responsibility, hailing a “heroic” act, came from a splinter group of the Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahvaz (ASMLA). The European-based separatists, with a history of bombing civilians and blowing up pipelines in Iran, have reportedly received Saudi cash.

Like clockwork, days later in Denmark, a Norwegian citizen of Iranian descent was found conducting reconnaissance near the residence of the ASMLA leader, who goes by the name Habib Jabor.

“There is sufficient basis to conclude that an Iranian intelligence service has been planning the assassination of an individual living in Denmark,” the Danish Security and Intelligence Service said in October.

(The ASMLA later distanced itself from initial claims for the Ahvaz attack. Ironically, the Islamic State made a more convincing claim, and Iran within days launched missiles at an ISIS base in Syria, portraying the strike as revenge.)

Denmark isn’t an isolated case. European officials also accuse Iran of a Paris bomb plot against an opposition rally last year – for which an Iranian diplomat who purportedly provided explosives is now in custody – as well as two assassinations in the Netherlands in 2015 and 2017.

The alleged bomb plot and assassinations recall the first two decades after Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, when an estimated 160 dissidents were killed by Iranian agents abroad, more than a third in Europe.

Covert support for separatists

Iran denies all the recent charges. But top Iranian officials also say their intelligence agencies have shifted from defensive to offensive operations amid an American “maximum pressure” campaign that imposes ever-tougher sanctions and a renewed covert war with the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

Making its threat perception more acute, Iran suspects its arch foes of backing ethnic minority Arab, Kurd, and Baluch separatist groups, as well as regime opponents like the Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK), a cult-like group once on the U.S. terrorism list. Such groups have been stepping up anti-regime actions, including a mid-February suicide attack that killed 27 IRGC troops in southeast Iran and was claimed by Baluch militants of Jaish al-Adl, or Army of Justice.

Without providing a timeline or locations, Iran’s Intelligence Minister Mahmoud Alavi claimed April 18 that Iran had disrupted 116 teams linked to the MEK, 114 ISIS cells, and neutralized 188 plots, all while exposing scores of CIA sources.

The uptick of lethal action and thwarted plots in Europe, analysts say, is a direct response to Iran’s evolving threat perception. The aim of Iran’s intelligence services, they add, is to show those officially deemed to be “terrorists” that the Islamic Republic can and will exact revenge, anywhere, and to remind those opponents newly flush with foreign cash and other covert support that Iran can thwart them.

“The security environment for Iran has changed, in terms of the regional and global security threat, and they have to respond to that,” says Saeid Golkar, an Iran expert at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

“Right now the Islamic Republic is under huge pressure,” says Mr. Golkar. “They are thinking about survival, so they have to undermine, they have to kill the enemies. Not all of the enemies, of course, but the more outspoken, the more active enemies, to create fear among dissidents.”

Ayatollah Khamenei set the tone a year ago, when he told Ministry of Intelligence staff that “the enemy is waging a widespread and complicated intelligence war” and that “we need offensive measures.” Indeed, the published budget of the ministry’s new Foreign Intelligence Organization saw a doubling of funding last year.

Awkward time for diplomats

The accusations against Iran bolster the Trump administration’s stance as it pressures European nations to sever ties with Iran and makes no secret of its wish for regime change in Tehran.

But if Europe is again becoming an external battlefield for Iran, it’s at an awkward time for European diplomats trying to save the landmark 2015 Iran nuclear deal. European leaders who oppose the unilateral U.S. withdrawal from the deal have sought to sidestep some U.S. sanctions to ensure continued Iranian compliance.

“The Europeans are in a very awkward position today, because they want to see the deal preserved, but they have so many of their own deep frustrations with Iran that, in order to keep the deal, they have to compromise and accept embarrassing situations,” says Sanam Vakil, an Iran specialist at Chatham House in London.

And it’s no less awkward for the government of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, which says the allegations against Iran aim to damage EU-Iran relations.

“There is deep, deep paranoia inside Iran among hard-liners, stemming from Mr. Khamenei himself, about opposition groups, about all of this pressure against Iran,” says Ms. Vakil. “We’ve seen patterns of irrational behavior so many times in the past. This isn’t a surprise, just a surprise that it comes now.”

In Belgium, for example, authorities last June stopped a pair of would-be bombers on their way to the annual MEK rally, near Paris, which was addressed by President Donald Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani.

The Iranian-Belgian couple carried a pound of high explosives, allegedly given to them by an Iranian diplomat based in Vienna, Asadollah Asadi, who was arrested in Germany.

The European Union in January sanctioned the diplomat, a deputy intelligence chief in Tehran – Saeid Hashemi-Moghaddam – and Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence itself.

But while Iran paid a diplomatic price, the alleged plot also sent a message to the MEK, which has seen its rising star accelerate during the Trump era.

The MEK was removed from the U.S. terrorism list in 2012, in no small part due to a campaign by dozens of former senior U.S. officials, who received tens of thousands of dollars in speaker’s fees that experts say were secretly bankrolled by Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Pro-MEK speakers included Mr. Giuliani and John Bolton, now Mr. Trump’s national security adviser, who has frequently called for regime change in Iran and addressed the Paris MEK meeting eight times.

Internal rivals ...

Analysts point to another possible reason for the surge in attacks in Europe: institutional and political rivalries in Iran. In 2009, after widespread protests that followed Iran’s disputed presidential election that year, Iran undertook a reorganization of rival intelligence agencies. Some top security officials complained that the Ministry of Intelligence was sympathetic back then to what hard-liners called the “sedition.”

“In 2009 the Ministry of Intelligence, which failed to prevent the uprisings, was publicly humiliated as Ayatollah Khamenei personally intervened to purge the ministry” and inserted several IRGC intelligence officers, says Ali Alfoneh, an Iran expert at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington.

“Reactivation of the assassination program may perhaps be the Intelligence Ministry’s attempt at demonstrating its usefulness to the regime,” says Mr. Alfoneh, author of a book on the IRGC. By contrast, he says, IRGC intelligence staged operations further afield in Georgia, Thailand, and India years earlier that “tended to be less successful.”

The MEK bomb plot “does not follow the pattern of IRGC acting reckless and the Intelligence Ministry being more professional,” says Mr. Alfoneh.

Still, he says, European services “managed to track communications between those arrested all the way to a specific office in the Ministry of Intelligence, and not the IRGC Intelligence Organization.”

European officials also accuse Iran of “probable involvement” in the 2015 contract killing by Dutch criminals of Mohammad Reza Kolahi. The former MEK member, living as an electrician under an assumed name in the Netherlands, was believed responsible for a 1981 bombing of a Revolutionary Council meeting in Tehran that killed 73.

Likewise, in late 2017, the founder of the separatist ASMLA, Ahmad Molla Nissi, was gunned down outside his home in The Hague. His daughter told Reuters the assassination showed that “conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran … is spreading to Europe.”

... and ‘rogues’

Adding another variable, Iran’s former ambassador to Germany, Ali Majedi, suggested in January that rogue elements might have been behind the actions in Europe – as freelancing hard-liners have acted in the past, without official knowledge or approval.

Europe is “facing a dual policy from Iran. They have presented some evidence which we cannot easily disprove,” Mr. Majedi told the ISNA news agency. “Domestically, we are faced with such an issue as rogue operations. Can we deny that outside the country these actions also take place?”

Iran’s Foreign Ministry quickly distanced itself from the comments.

Could aid for Notre Dame help rebuild France’s crumbling history?

The $1 billion in donations to rebuild Notre Dame cathedral have stirred a new sense of awareness across France. Perhaps the fire has awakened the need to preserve local history too.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Peter Ford Staff writer

While private donors from France and around the world have raised more than $1 billion to save Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral after the April 15 fire, other impoverished monuments have not garnered nearly as much sympathy.

The French state currently spends around $360 million on cultural heritage, just 3% of the Culture Ministry’s annual budget. Around 4% of historical monuments are owned by the state – like Notre Dame – while the rest must rely on private donations. Petit patrimoine – small heritage sites like privately inherited homes, castles, or village windmills – often feel the brunt of the burden.

That was the case in Choisy-au-Bac, a town in the Oise region, which leaned heavily on individual philanthropy to repair its aging Sainte-Trinité church. The town raised about one-fourth of building costs for the first two of three construction phases. Now the town hall hopes the third phase will benefit from the donating spree that followed the Notre Dame fire.

“People are becoming more aware after the Notre Dame fire of a desire to preserve our cultural heritage,” says Deputy Mayor Cécile Gambier. “It’s going to make them think, this monument won’t be here forever. We shouldn’t wait until it’s falling apart to try to save it.”

Could aid for Notre Dame help rebuild France’s crumbling history?

The village church in Saint-Gilles is not a thing of great beauty. It was converted in the mid-19th century from a storehouse and vat rooms that had belonged to a local winery, and it feels like it. A priest comes to celebrate Mass only four times a year and the building serves mainly as an officially recognized refuge for bats.

But when the bells ring out from the church belfry – which they now do every half hour, as well as at noon and suppertime – it’s a reminder for anyone within earshot of the dedication of locals to save this village mainstay. When Maxime Petitjean became mayor in 2014 of this sleepy, canal-side village in Burgundy, the church bells were in complete disrepair.

“I’m not necessarily a believer,” says Mr. Petitjean, “but a village needs church bells.”

But fixing the bells and the automatic system came with a bill of $38,000. The village raised $15,500 from local and national government institutions and collected $14,000 from private donors. The town hall covered the rest of the work itself.

The village church in Saint-Gilles is one of thousands of churches, cathedrals, and other historical buildings in France in need of repairs. And while private donors from France and around the world have raised more than $1 billion to save Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral after its iconic spire went up in flames on April 15, other impoverished monuments have not garnered nearly as much sympathy.

As state funds run dry, the French are looking to grassroots efforts like startup organizations and crowdfunding platforms to save local churches and other beloved monuments. In a nation that squirms at the flaunting of money, the Notre Dame fire has shone new light on the need for more funding dedicated to cultural heritage and a shift in how people here see their role in preserving it.

“We can hope that there will now be a realization on the part of the public that local heritage is fragile and that they can contribute to its preservation,” says Nathalie Heinich, an author and sociologist on cultural heritage at Paris’ National Center for Scientific Research. “But we don’t have much of a culture of private philanthropy in France. Most people assume that since we pay taxes, it’s the state that should invest, and if we donate, it’s out of personal enjoyment and not due to any moral obligation.”

‘A serious lack of funds’

The French state currently spends around $360 million on cultural heritage, just 3% of the Culture Ministry’s annual budget. Around 4% of historical monuments are owned by the state – like Notre Dame – while the rest must rely on private donations.

Last year, French television presenter Stéphane Bern launched the country’s first heritage lottery in an attempt to get citizens involved in preserving France’s most dilapidated monuments. But unlike after the Notre Dame fire, funding came up short.

“The initiative showed us that there is a serious lack of funds,” says Julien Noblet, an architectural historian at the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art in Paris. “We’re always in need of more money, especially when it comes to local heritage projects.”

Mr. Noblet says that petit patrimoine – small heritage sites like privately inherited homes, castles, or village windmills – often feel the brunt of the burden, not benefiting from much state help and relying primarily on local generosity.

That was the case in Choisy-au-Bac, a town in the Oise region, which leaned heavily on individual philanthropy to repair its aging Sainte-Trinité church. When the state couldn’t find enough money, the town hall sent out letters to locals urging them to contribute and held a fundraising concert in the church’s honor.

The town raised about one-fourth of building costs for the first two of three construction phases. Now the town hall hopes the third phase will benefit from the donating spree that followed the Notre Dame fire, which saw France’s wealthiest families donating as much as 200 million euros ($225 million) each toward reconstruction efforts.

“People are becoming more aware after the Notre Dame fire of a desire to preserve our cultural heritage,” says Cécile Gambier, deputy mayor in charge of culture and heritage in Choisy-au-Bac. “It’s going to make them think, this monument won’t be here forever. We shouldn’t wait until it’s falling apart to try to save it.”

Meanwhile, the National Heritage Fund (La Fondation du Patrimoine) continues its drive to preserve the country’s local heritage. The organization, which funnels donations from individuals to cultural heritage projects and offers donors a 66% tax deduction, currently manages 3,000 campaigns around the country.

At least one of its projects has seen an uptick in donations since the Notre Dame fire, and the National Heritage Fund says it hopes the trend will continue.

“Smaller heritage sites are what preserve a town’s attractiveness, provide jobs, and contribute to the desire to live in a place,” says Célia Verot, the managing director of the National Heritage Fund. “We hope that the generosity we’ve seen towards Notre Dame will extend further to the rest of the country.”

Often smaller or lesser-known heritage sites fail to raise money due to a lack of visibility. Mayor Christian Teyssèdre of Rodez, an ancient city in the south of France, has railed publicly against his region’s government for quickly offering $1.7 million to help repair Notre Dame. Last year it refused to contribute anything to the restoration of Rodez’s Gothic cathedral, even though bits are falling off it.

And just outside Paris, the Basilica of Saint-Denis – a medieval abbey church from the 12th century – has been fighting to restore its north bell tower and spire since they were destroyed by a series of tornadoes in the mid-1800s. Even though the basilica boasts stained-glass rose windows and an overall aesthetic almost identical to Notre Dame, it still lacks the several millions of euros it needs for reconstruction.

“The Basilica of Saint-Denis is fundamental in terms of history. There’s no such thing as a small historical building. Everything is history,” says Sandrine Victor, a lecturer in medieval studies at the Institut National Universitaire Champollion in Albi, France. “But the priority [for the state] is on tourism.”

Citizen groups step in

As national campaigns fail local heritage sites, a trend toward private philanthropy is quietly brewing. In Saint-Denis, locals created the nonprofit Suivez la Flèche as a way to raise money for their basilica, while citizen group La Tour de Marmande was launched to save the crumbling Marmande castle in the west of France. Crowdfunding sites Dartagnans and Adopte un Château allow people to adopt one of the approximately 600 castles in danger of disappearing across France.

At the same time, there’s also a need for more manual labor – especially those trained in restoring historical buildings. The Compagnons du Devoir, a guild association that trains some 10,000 people each year in craft and medieval traditions, alerted the French government in the wake of the Notre Dame fire that more trained workers were needed in the building trade.

It’s a renewed call to nonprofits like Rempart, which helps individuals get involved in restoration efforts. Since 1979, Rempart has helped ordinary citizens find volunteer work on construction sites of national heritage projects around the country.

Still, for many town halls in France, money is the core issue when it comes to repairing their local church or windmill. Mayor Petitjean of Saint-Gilles thinks that most people are attached to their local heritage and are more likely to give to something in their village than to a national project. But the call for donations hasn’t been easy.

“I think we did quite well to raise as much as we did from villagers,” he says. “But we could have done with a donation like the ones some millionaires are making now to Notre Dame.”

Revenge of the nerd culture: 2019 may mark peak geek chic

Sci-fi and fantasy used to be the province of those who got their lunch money bullied out of them at recess. Now Hollywood can't get enough. Geek has gone totally mainstream. So now what?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Stephen Humphries Staff writer

The seeds of today’s all-encompassing geekdom were planted a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.

In 1977, a Boomer generation of parents who loved “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “The Lord of the Rings” books took their kids to see “Star Wars.” Just as Beatlemania inspired a generation of kids to pick up guitars, “Star Wars” inspired the next one to pick up toy lightsabers. Even so, as recently as the turn of the new millennium, adults were less public about their love of sci-fi and comics.

“For a really long time, being a nerd or being into nerdy things was seen as something kind of embarrassing or culturally taboo,” says Sam Maggs, author of “The Fangirl’s Guide to the Galaxy.” “The advent of social media and online culture really solved that problem because suddenly all of the people who liked this stuff felt that they could form their own communities and find their people online.”

The result is beloved TV and movie franchises that Hollywood is loath to part with. But as “Game of Thrones” and the Avengers series draw to a close, some observers wonder if studios will embrace fresh ideas for tempting audiences.

Revenge of the nerd culture: 2019 may mark peak geek chic

Outside a Boston cinema, Jeffrey McNamara and Brian Antonelli are huddled in mutual support. Co-hosts of a pop-culture podcast titled “Mac & Gu,” they’ve just finished watching “Avengers: Endgame.”

“I cried a little bit,” admits Mr. McNamara, a millennial clad in a Spider-Man T-shirt.

As with two other immensely popular series, “Star Wars” and “Game of Thrones,” this year marks the end, of sorts, for the Avengers. All three sagas are regular subjects of discussion on the geeky podcast, which discusses TV and movies as if they were sports. For the duo that hosts it, “Avengers: Endgame” is the superhero version of an all-star game. The culmination of 22 movies with interlinked storylines, it features among others Captain America, Captain Marvel, Hulk, Iron Man, and Thor. Plus a talking raccoon from outer space.

“We had butterflies in our stomachs,” says Mr. McNamara, “almost like a sporting event, like you’re gonna watch your favorite team play.”

A few generations ago, grown men might have been ridiculed for expressing more interest in the heroics of Ant-Man than Tom Brady. But fare that was once deemed purely adolescent and nerdy – science-fiction, fantasy, and comic-book series – is not just mainstream but all-pervasive. That’s reflected by the staggering global record $1.2 billion for the opening weekend of “Avengers: Endgame.” Even after such lucrative franchises end, observers say “nerdy” fare will continue to drive society’s shared cultural experiences. The challenge for Hollywood is how to keep what comes next fresh.

“The thing that’s different now is just how well major corporations have been able to capitalize on that sort of transition from geek culture to mainstream – and also of nostalgia,” says film critic Lindsay Ellis, whose YouTube channel has more than 600,000 subscribers.

The seeds of today’s all-encompassing geekdom were planted a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away. In 1977, a Boomer generation of parents who loved “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “The Lord of the Rings” books took their kids to see “Star Wars.” Just as Beatlemania inspired a generation of kids to pick up guitars, “Star Wars” inspired the next one to pick up toy lightsabers.

Directors such as George Lucas and Steven Spielberg changed Hollywood by ushering in the modern blockbuster and with it the attendant sequels, prequels, spinoffs, merchandising, and theme parks. But as recently as the turn of the new millennium, adults would sooner admit to building model railroads in their basement than to reading “Star Wars” spinoff novels such as “Lando Calrissian and the Starcave of ThonBoka.”

“For a really long time, being a nerd or being into nerdy things was seen as something kind of embarrassing or culturally taboo,” says Sam Maggs, author of “The Fangirl’s Guide to the Galaxy: A Handbook for Girl Geeks.” “The advent of social media and online culture really solved that problem because suddenly all of the people who liked this stuff felt that they could form their own communities and find their people online.”

By 2007, the greater visibility of geek culture was reflected by the debut of “The Big Bang Theory,” a sitcom about four lovable nerds whose hobbies included games of “Rock-paper-scissors-lizard-Spock.” The CBS show, which takes its final bow in May, exemplified how entertainment conglomerates had ramped up marketing for related products. Produced by Warner Bros., which owns DC Comics, “The Big Bang Theory” included numerous tie-ins to brands such as Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman.

‘They have to move forward’

The acknowledged leader of the Hollywood business model is Marvel, whose expanded universe has made more money than Stark Enterprises. It has hewed close to established comic-book storylines so as not to upset the existing fanbase.

“It’s basically just stories they’ve already read before, but people don’t want to disappoint the fans by telling them a different way. So they just basically copy-paste it instead of making something different,” says Stephanie Marceau, a writer for Screen Rant and Nerd Bastards.

But even the most durable franchises eventually have to change. The Transformers have mutated more often than Optimus Prime, most recently shifting from Michael Bay’s five movie series to last year’s reboot in the form of “Bumblebee.” Tampering with established properties can be a commercial liability. When auteur director Rian Johnson usurped established norms in “Star Wars: The Last Jedi,” it created a disturbance in the fan force.

“Right now we see this tension between content creators and fans. And if the fans feel, as happened with the last ‘Star Wars’ movie, that it wasn’t made the way they wanted, they’re going to fight back. And there’s this discussion out there, ‘Who owns these properties?’” says Ty Burr, film critic of The Boston Globe. “Bottom line is the corporations own the properties.”

Jason Bischoff, former director of Hasbro’s Global Franchise Creative team, compares franchises to monorails. There’s a constant tension between those in the front trying to drive the monorail forward and those at the back who want to pump the brakes.

“There’s people constantly getting on, and there are people constantly getting off,” says Mr. Bischoff, who gave a 2017 TED Talk titled “The Rise of Geek Culture.” “But if we want them to stand the test of time, they have to move forward.”

Marvel has made cautious adjustments to its series, which will continue with a new phase after “Avengers: Endgame,” by slowly diversifying the gender and race of its lead characters. It has also changed up the tone and genres of each entry. For example, “Black Panther” plays like a spy movie, and “Thor: Ragnarok” is like a sci-fi road trip comedy. But there’s a limit to just how far Marvel will innovate. It’s not about to reboot “Howard the Duck” anytime soon.

“They’re risky in their way, but they’re not artistically strange,” observes Ryan Britt, author of “Luke Skywalker Can’t Read: And Other Geeky Truths.” By contrast, he observes, Tim Burton’s “Batman” movies were remarkably quirky in a way that modern blockbusters wouldn’t dare emulate. “You know, Christopher Walken is running around with giant penguins, and Michelle Pfeiffer is licking from a bowl!”

Small-screen innovation

But if big-screen movies cater to fan service in a bid to maximize global audiences, the smaller screen allows for riskier approaches to lower-budget escapist stories. That’s why Marvel’s short-lived series on Netflix, including “Daredevil” and “Jessica Jones,” were more tonally and narratively audacious than their big-screen cousins.

Similarly, the character-driven and thematically rich “Game of Thrones” has often been compared to the works of Shakespeare. (That said, it’s hard to imagine the Bard putting a zombie on a flying dragon.) Indeed, the most complex characters and most challenging drama are often on television, says Mr. Burr of The Boston Globe. That’s where many of the most creative writers and directors have set up camp. An example of that is Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon's upcoming Star Trek series, with Patrick Stewart reprising his role of Captain Picard.

Another reason to be optimistic: Hollywood is always looking for innovative creators of a geeky disposition. The next breakout storyteller may emerge from traditional publishing. That’s why Netflix recently snapped up the rights to numerous young adult books, says Ms. Maggs, who also wrote Marvel’s “Fearless and Fantastic!” The goal? Find the next Harry Potter.

“They sometimes wait until something is proven already to have a market in publishing before it moves into movies,” says Ms. Maggs. “There will always be an appetite for fresh stories.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A China-US trade deal may hinge on an honesty pledge

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Trade talks that began last year between China and the United States may finally be drawing to a close. While the world’s two leading economies have made much progress, a key missing part is any agreement to end Chinese theft of U.S. know-how. This point was made very clear last week by FBI Director Christopher Wray. He should know. The FBI is in charge of stopping economic espionage in the U.S.

Mr. Wray said China has “pioneered a societal approach to stealing innovation in any way it can from a wide array of businesses, universities, and organizations.” The FBI can do only so much against such theft, however, without China itself deciding that it can be as inventive as any other nation in science and technology. Perhaps it is because China has made some progress to honor and protect the creative works of inventors that it is difficult for negotiators to strike a final deal.

China may be asking for time to improve itself. Any final trade deal will need to both recognize China’s progress and speed it along.

A China-US trade deal may hinge on an honesty pledge

Trade talks that began last year between China and the United States may finally be drawing to a close. A large Chinese delegation is due in Washington next week. While the world’s two leading economies have made much progress, a key missing part is any agreement to end Chinese theft of U.S. know-how.

This point was made very clear last week by FBI Director Christopher Wray. He should know. The FBI is in charge of stopping economic espionage in the U.S.

Speaking at the Council on Foreign Relations, Mr. Wray said China has “pioneered a societal approach to stealing innovation in any way it can from a wide array of businesses, universities, and organizations.” The effort includes government spies, state-owned enterprises, private companies, and Chinese students and researchers in the U.S.

“At the FBI we have economic espionage investigations that almost invariably lead back to China in nearly all of our 56 field offices, and they span just about every industry or sector,” he said. The FBI chief charged China with stealing “its way up the ladder” and violating a rules-based world order that is based on fairness, integrity, and rule of law.

His strong words may reflect the frustrations of U.S. negotiators in striking a deal with China. They also reflect recent prosecution of several Chinese nationals and companies on such charges as patent infringement. In 2017, theft of U.S. intellectual property by China was valued at more than $600 billion.

The FBI can do only so much, however, without China itself deciding that it can be as inventive as any other nation in science and technology without stealing ideas. Perhaps it is because China has made some progress to honor and protect the creative works of inventors that it is difficult for negotiators to strike a final deal. China may be asking for time to improve itself.

The best indicator of a shift is an improved system in China for the protection of intellectual property, both for Chinese and foreign companies. Last year, about a quarter of U.S. companies in China reported “insufficient protection” of their copyrights, patents, and trademarks. Still, many foreign firms are now winning more cases in special courts set up in China to deal with intellectual property. And under a ranking of patent systems in 51 countries devised by the University of Liverpool and Copenhagen Business School, China has more than doubled its scores in some categories, such as speed in deciding a case, over the last few years.

China still has far to go. Its patent system is as weak as those in Russia, Indonesia, and Mexico. (The U.S. ranks 15th on the index, behind countries like Japan and Germany.) It is difficult being branded as a global thief. Any final U.S.-China trade deal will need to both recognize China’s progress and speed it along.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The value of repentance

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

Yearning to overcome the willful, impulsive tendencies that had plagued her for years, today’s contributor turned to God. The realization that goodness is the fundamental essence of all God’s children made a tangible difference in her perspective and behavior and resulted in the healing of a fever.

The value of repentance

Nineteenth-century Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle observed, “Of all acts, is not, for a man, repentance the most divine?” The Greek word “metanoia,” often translated as “repentance” in the New Testament, suggests “a transformative change of heart” (merriam-webster.com). To me, this takes repentance out of a narrow context of simply feeling regret or guilt and implies making a fresh start from a better basis.

A few years back I learned a great lesson in repentance when, in an act of stubborn will, I damaged our brand-new car. Although my husband had been certain that the car wouldn’t fit in our garage, I was quite sure I could make it fit. So I waited until he went to work and tried it – eventually bashing in the back end of the car. I felt awful.

Willfulness, including impulsive action, was nothing new to me. I’d been trying for years to stop my tendency toward it. I felt so upset about this latest incident that I became ill with a high fever. I was truly ready and willing to be healed of this character fault once and for all. But how?

As a student of Christian Science, I was familiar with its basic tenets, which are laid out in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy. One of these tenets addresses sin head on and shows how spiritual understanding destroys both the wrongdoing and its effects. Its premise is that evil is unreal – that is, has no basis in God, who is wholly good and is All – and thus has no real power over God’s creation. It begins: “We acknowledge God’s forgiveness of sin in the destruction of sin and the spiritual understanding that casts out evil as unreal” (p. 497).

“Sin” means different things to different people. My study and practice of Christian Science has led me to understand sin as any action that suggests we are separate from the source of all good, from God. And I certainly was feeling separate from good as I lay in bed with a fever fretting over what I had done!

I had felt regret, guilt, and shame before, and while these feelings would eventually fade somewhat, nothing much about my willful behavior changed. This time, I prayed for a fuller repentance – for the spiritual transformation that would result in reformation. The tenet cited above doesn’t blindly exonerate sin and its effects. It concludes: “But the belief in sin is punished so long as the belief lasts.” Expunging sin involves self-examination – seeing ourselves through a spiritual lens, and on this basis challenging the belief in the morbid influence of evil in our lives. This allows us to think and live by a higher standard.

I thought about the Apostle Paul’s words, “All things work together for good to them that love God” (Romans 8:28). I reasoned that it is through my relation to God as God’s child – the spiritual expression of His powerful and active goodness – that I can be good. God is All, so there is nothing to degenerate or attack God. Therefore each of us, as divinity’s reflection, is safe, uncorrupted, free from defect, capable of expressing God’s goodness. Mrs. Eddy describes good as “the primitive Principle of man” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 14). The real source of our goodness is God, the universal Principle of divine good. Through the power of Christ, the true idea of God, we can discover the goodness we are all capable of.

I prayed with these ideas for about two hours that night. Then I fell asleep. When I woke, the fever had broken and I was well. When my husband woke, he felt a big change, too – his anger had been replaced with calm. The car was easily repaired, and we made new parking arrangements. Best of all, I had a renewed sense of my ability – my divine right – to put a stop to the willful, impulsive behavior. And from that point on, those tendencies diminished noticeably.

God’s nature as good itself establishes goodness as natural. Understanding this can bring about a change of heart that washes one clean of sin and its often painful results. This spiritual repentance comes from identifying God as the source of all good and acknowledging that this goodness is the permanent, fundamental essence of us all – and helps us to bring out the very best in ourselves and others.

A message of love

All eyes on a new emperor

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back tomorrow when correspondent Taylor Luck looks at how women’s push into the workforce in Jordan has dramatically changed how men view them.