- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- To impeach or not to impeach? That may be the wrong question.

- In Netanyahu’s Israel, concern for a democracy pushed to its limits

- Canada’s indigenous try to break vicious cycle tearing families apart

- Conflict closed schools. A teen teaches himself, one toy car at a time.

- ‘My first mission was Normandy’: World War II pilots recall role in history

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The tiny crack that could change how the world sees Islam

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

When non-Muslims think of Islam, it is likely that they are thinking of an image largely crafted by Saudi Arabia. It is an image that Saudi Arabia has aggressively proselytized in the Sunni Muslim world and beyond through its wealth and influence: a strident conservatism that, for instance, only recently saw women as fit to drive.

But this past week, that image showed signs of cracking.

Outside the Muslim world, the disagreement might have seemed a small thing. Three Arab countries rejected Saudi Arabia’s pronouncement that the holy month of Ramadan ended Tuesday. They proclaimed it ended Wednesday. But for Taylor Luck, our correspondent in Jordan, that flicker of discord bespeaks something much bigger: Saudi Arabia is paying the price for politicizing religion.

Saudi Arabia’s interpretation of Islam, called Wahabbism, has been the country’s “main export the past four decades and was their attempt to expand and cement their influence across the Arab world,” he says. “This reductionist or austere interpretation went unchecked until it invaded almost every major town and city in the Arab world.”

“The fact that states are now showing they are willing to push back, albeit gradually, is a sign that Saudi’s monopoly or unquestioned hegemony over Islam is not as secure as it once was – or as they think it is.” For a religion that, in many places, is far more diverse and tolerant than the image of Wahabbism presents, it is the seed of a potentially powerful change.

Today our five stories include a look at Israel’s moment of decision for democracy, Native Canadians’ efforts to reforge the system that sought to break them, and an incomparable glance back at D-Day through the eyes – and the cockpit – of two pilots who lived it.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

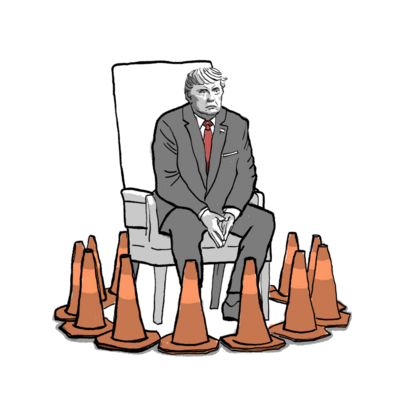

To impeach or not to impeach? That may be the wrong question.

Impeachment is presented as a binary choice, but Congress has other options for dealing with perceived presidential offenses.

Now that retired special counsel Robert Mueller has spoken publicly about his Trump-Russia investigation, effectively leaving next steps to Congress, the question of impeachment has gained fresh urgency. The Mueller report found no provable conspiracy between Trump associates and Russia in the 2016 election, but it detailed 10 examples of potential obstruction of justice by the president.

But Congress is not facing a binary choice, “impeachment, up or down.” There are many options for responding to a president who defies subpoenas and whom a significant portion of Americans view as unfit for office. Among them is another form of sanction for perceived wrongdoing: censure, or a formal reprimand in the form of a majority resolution by one or both chambers of Congress.

Unlike impeachment, which is the constitutional procedure for expelling a president before the end of his term, censure is not mentioned in the Constitution. But it’s an option – rarely used – that would at least convey moral outrage over certain presidential actions.

“It’s a symbolic gesture that would please no one, but it might be the best alternative,” says a Democratic strategist, speaking on background.

To impeach or not to impeach? That may be the wrong question.

Yes or no: Do you favor impeaching President Donald Trump? That’s the question Democratic politicians around the country are being battered with – at town halls, in fundraisers, during TV interviews. Support for impeachment has been slowly rising among Democrats in Congress, within the large Democratic presidential field, and among the American people.

Now that retired special counsel Robert Mueller has spoken publicly about his Trump-Russia investigation, effectively leaving next steps to Congress, the question has gained fresh urgency.

But “impeachment, up or down” may not be the right question. Indeed, in responding to a president who defies subpoenas and whom a significant portion of Americans view as unfit for office, Congress is not facing a binary choice. The options are many, including another form of sanction for perceived wrongdoing: censure, a formal reprimand in the form of a majority resolution by one or both houses of Congress.

“It’s a symbolic gesture that would please no one, but it might be the best alternative,” says a Democratic strategist, speaking on background.

Unlike impeachment, which is the constitutional procedure for expelling a president before the end of his term, censure is not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. But it’s an option – rarely used – that would at least convey moral outrage over certain presidential actions, for those who feel it. The Mueller report found no provable conspiracy between Trump associates and Russia in the 2016 election, but it detailed 10 examples of potential obstruction of justice by the president.

Democratic pollster Mark Penn, a critic of the Mueller investigation, agrees that “censure makes sense” – in part because holding such a vote against the president in the Democratic-controlled House would put “a lot of Republicans in a bind.” Mr. Trump enjoys 90 percent support among Republican voters, which makes it politically dangerous for GOP members to vote against him. So far, the only Republican in either chamber to come out in favor of impeachment is the libertarian-leaning Rep. Justin Amash of Michigan.

A House censure vote against Mr. Trump could hold some political peril for Democrats. As with impeachment, Mr. Trump could wear a censure resolution as a badge of honor. And the party’s liberal base would likely perceive it as a mere slap on the wrist in the face of what many Democrats see as egregious or even illegal presidential behavior. But would it lead them to stay home in the 2020 election? Mr. Penn is doubtful.

“It’s pretty unlikely activists will pass on an opportunity to vote against Trump,” the pollster says.

For now, though, debate among Democrats centers squarely on impeachment – or more precisely, whether to launch a formal impeachment inquiry. The hope is that such an inquiry would unearth further evidence of presidential wrongdoing, either in matters related to the Mueller investigation or elsewhere, including Mr. Trump’s financial dealings.

In effect, a preliminary impeachment inquiry is already starting, though not in name. The warm-up act comes Monday, when former Nixon White House counsel John Dean testifies before the House Judiciary Committee on obstruction of justice, along with former U.S. attorneys and other legal experts. Mr. Dean was the star witness against President Richard Nixon in the 1973 Watergate hearings that eventually led to the 37th president’s resignation.

House Judiciary Chairman Jerrold Nadler has announced additional hearings in coming weeks that will focus on “other important aspects of the Mueller report.”

On another track, the full House is scheduled to vote Tuesday on whether to hold Attorney General William Barr and former Trump White House counsel Don McGahn in contempt for failing to deliver subpoenaed documents and, in Mr. McGahn’s case, for defying a subpoena to testify. The contempt resolution is expected to contain language that boosts Democrats’ efforts to obtain Trump tax returns.

So far, no key witnesses in the Trump-Russia inquiry, including Mr. Mueller himself, have agreed to testify in Congress. In a rare public statement last week, Mr. Mueller said “the report is my testimony.” But Democrats still want him to appear before Congress, if only to give voice to key points from his report, based on the assumption that few Americans will read the 448-page tome. Democrats have yet to subpoena Mr. Mueller.

Meanwhile, the list of House Democrats supporting an impeachment inquiry is growing – now at 59 (out of 235), according to a New York Times count. Among the two dozen Democrats running for president, 11 now support an inquiry. Overall public support for impeachment is also growing, though still not a majority. Mr. Penn’s latest Harvard-Harris poll shows support for impeachment and removal from office at 37 percent, up from 28 percent in April; support for “no action” is at 42 percent, and 20 percent favor censure. Among polled Democrats, 60 percent favor impeachment; among independents, it’s 36 percent.

Time is not on the pro-impeachment side, barring an explosive revelation. With each passing day, the November 2020 election takes up more oxygen and boosts the argument that the voters should decide Mr. Trump’s fate. Democrats are keenly aware that, based on what’s known, the Republican-controlled Senate would not come close to convicting and removing the president even if he were impeached by the House.

So the calendar, in effect, is House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s friend, as she tries to fend off pro-impeachment forces within her caucus. Speaker Pelosi maintains impeachment is still on the table, but only in the event of a major new revelation.

Here the argument becomes circular: The likeliest path to explosive new information, if it exists, would come via a formal impeachment inquiry, congressional Democrats say. They believe it would boost their case in court as they seek access to grand jury testimony and documents underlying the Mueller report. But most House Democrats fear a formal House move toward impeachment could boost Mr. Trump politically, as it did President Bill Clinton in 1998.

“Right now, if the House impeached Trump, the Senate wouldn’t convict. That inoculates him,” says Rick Tyler, an anti-Trump Republican commentator. “He’ll say he was exonerated. He’ll say it was all a witch hunt.”

Centrist House Democrats are also advising caution.

“I think people now are just all about the contempt vote next week,” a leading House moderate told reporters on background Tuesday. “Hopefully that will let off enough steam to avoid the impeachment vote. I think people still think – like me – oversight, oversight, oversight, you know? And use the courts.”

Whether there’s potential for a modern-day John Dean to step forward is another question. Historian Ken Hughes has his doubts.

Mr. Dean had agreed to become a key witness in exchange for a lighter sentence, stemming from his involvement in the Watergate scandal. But “it’s not clear now that the Democrats in the House have that kind of leverage over any current members of the Trump administration,” says Mr. Hughes, a research specialist and expert on Watergate at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

With former administration officials, there are major disincentives to cooperating with Congress. Some may be motivated by continuing loyalty to the president. There are also professional reasons to avoid testifying, Mr. Hughes says.

“Former Trump administration officials can fear being ostracized and fear losing job opportunities,” he says. “They can fear losing access to their former colleagues in the administration, which makes them less useful as lobbyists.”

Staff writer Jessica Mendoza contributed to this report.

In Netanyahu’s Israel, concern for a democracy pushed to its limits

Are elected leaders above the law? How crucial is an independent judiciary? Democracies worldwide are increasingly facing these questions. In Israel, they are at the center of concerns about Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s efforts to retain power.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

Dan Meridor, a former justice minister who once worked closely with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, is among those warning of a threat to Israel’s democracy.

Mr. Netanyahu, who has three corruption cases pending against him, was attempting to gain immunity from prosecution while in office and also give lawmakers power to override the Israeli Supreme Court. His 11th-hour maneuvers raised alarm bells among many in Israel – from the left and right – who saw in them an attempt to override democracy itself.

The so-called immunity bill he sought is now on ice because the Knesset, led by Mr. Netanyahu’s ruling Likud party, voted to dissolve and head to new elections rather than give opposition parties an opportunity to form a government – an audacious move without precedent in Israeli history.

These developments have many in Israel worrying it is headed toward a diminished form of democracy. Pointedly, Israeli observers see what is happening here as very much part of the broader backlash against the post-World War II norms of liberal democracies around the globe.

“The courts by definition have a role in democracy,” says Mr. Meridor. “Limitless government is not democratic.”

In Netanyahu’s Israel, concern for a democracy pushed to its limits

Israeli lawmaker Ayman Odeh, an Arab citizen, looked out from the podium of Israel’s parliament in Jerusalem and tried to keep a straight face as he made an “announcement.”

“Seven minutes ago,” he said, “Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu spoke to me, and he said he is willing to withdraw from the occupied territories and also to cancel the nation-state law, and that he supports not only civil equality but also national equality, and that he's willing to recognize the Nakba and fix the historical wrong – in return for the immunity law.”

Almost instantly it was recognized as a spoof, offering one of the only moments of comic relief on a night of political crisis as Mr. Netanyahu scrambled last Wednesday in a failed bid to meet the deadline for forming a new coalition government.

Bursts of laughter filled the Knesset floor at the laundry list of purportedly and improbably redressed Palestinian political grievances. But the joke offered sad commentary on the state of democracy in Israel.

The immunity law Mr. Odeh was referring to was a bid by Mr. Netanyahu, who has three corruption cases pending against him, to ensure support for a bill that would grant him immunity from prosecution while in office.

Mr. Netanyahu denies the charges and says the cases were manufactured by those bent on ousting him from power. But to secure that immunity he also had been working to curb the powers of the Israeli judiciary, pushing for yet another law that would give lawmakers the authority to uphold laws the Israeli Supreme Court strikes down.

Mr. Netanyahu’s 11th-hour maneuvers raised alarm bells among many in Israel – from the left and right – who saw in them an attempt to override democracy itself.

But in the speed-of-light pace that drives Israeli politics, the so-called immunity bill is now on ice because the Knesset, led by Mr. Netanyahu’s ruling Likud party, voted to dissolve and head to new elections rather than cede the opportunity to the opposition parties who were next in line to try to form a government. The audacious move, without precedent in Israeli history, came just seven weeks after the most recent elections were held.

Combined with trends over the last decade, these developments have many in Israel worrying it is headed toward a diminished form of democracy – one that enables a longtime leader like Mr. Netanyahu to create something of a cult of personality, solidify power, limit the rights of the Arab minority, and crack down on dissent.

Pointedly, Israeli observers see what is happening here as very much part of the broader backlash against the post-World War II norms of liberal democracies around the world.

Likud ‘Old Guard’ strikes back

Dan Meridor, a former justice minister who once worked closely with Mr. Netanyahu, is among a handful of veteran Likud members who are warning of a threat to Israel’s democracy.

Historically, the Likud party advocated strongly for the rights of the political minority, drawing on its founding movement in early 20th-century Europe, where Jews advocated for themselves as national minorities. Informed by that ethos, Likud founder Menachem Begin, a longtime opposition leader before becoming prime minister, continued to advocate for a strong judiciary.

Mr. Meridor, whose father was also a lawmaker and was close with Mr. Begin, points out that the party was established with the name Likud-National Liberal Movement because liberal democracy and Jewish nationalism were its twin causes.

“These two values are why Likud was what it was – not extreme right nor extreme left – and why a main defender of the Supreme Court, Begin, wanted the right of judicial review of the Knesset,” says Mr. Meridor.

“As a Jew I can say we have been part of a minority for 2,000 years in the Diaspora,” he says. “When you are a minority it is very simple to be for human rights, but the real test is when you are a majority. There is a moral test that is basic to my idea to what Zionism is all about – not (the notion) that we are a majority and who cares about the rest?”

This shift in conceptions of democracy, he posits, is connected to modern technology that allows leaders to send inciting messages directly to the people: “You speak directly, tweet simple, negative, strongly emotional signals, and you win elections. But can you run a country? I am not sure.”

Mr. Meridor rejects accusations from Mr. Netanyahu and others on the right that the judiciary is the enemy of the people, noting that “attacks on the (judicial) system and the values of the system is part of what we see in the world today.”

“It’s totally baseless and the opposite of truth. The courts by definition have a role in democracy,” even when people don’t agree with their rulings, the former justice minister says. “Limitless government is not democratic,” he warns.

According to Yohanan Plesner, president of the Israel Democracy Institute, a Jerusalem think tank, the judiciary has increasingly become a target of two key interest groups: Jewish settlers and the ultra-Orthodox. The settlers see the courts as restraining their expansion in the West Bank, and the ultra-Orthodox fear the courts’ power to enforce equality for women.

Despite what Mr. Plessner calls “anti-judiciary” propaganda, however, he says surveys show 60% of Israelis trust the Supreme Court and don’t want it undermined, compared with 15% of the public who say they trust politicians more.

Annexation connection?

Most commentary in Israel around the erosion of Israeli democracy tends to focus on Mr. Netanyahu’s real-time political maneuvers. But Dahlia Scheindlin, an analyst and pollster, argues in a report for The Century Foundation, a progressive New York-based think tank, that the assault on democratic values should be viewed with a broader lens: as part of government designs on the annexation of at least portions of the West Bank.

“What has not been made clear enough is that it is fundamentally linked to annexation, laying the groundwork for one-state,” says Ms. Scheindlin.

“For a decade, the Israeli government has targeted and intimidated civil society, passed legislation to discriminate against minorities, and targeted the tools used for protest or protection – the media, the judiciary – while relentlessly redefining democracy in public rhetoric as unconstrained majority rule,” she writes in the report. “Israel’s slide into illiberal democracy can only be understood as part of an attempt to go beyond military or physical control and establish a political and legal foundation for permanent annexation of both land and people.”

Israel’s right-wing, Scheindlin argues, has been trying to redefine democracy in order to do this. And central to that plan has been, she says, “making the argument that Israel has been captured by the dictatorship of the judiciary and that is a minority oppressing the true voice of the people and that these unelected jurists are forcing values on an oppressed majority.”

An Arab-Jewish alliance

For decades, Israel’s advocates have described it as the most vibrant democracy in the Middle East. But in the run-up to April elections, Mr. Netanyahu made a comment directly at odds with that notion. Israel, he said, was not the state of all its citizens, but rather “only of the Jewish people.”

When his maneuvers around immunity and constraining the judiciary were at their peak, almost 100,000 Israelis flooded a Tel Aviv park to rally in “defense of democracy.” Protesters wore Turkish fez hats to symbolize that they did not want to go the way of their increasingly autocratic neighbor to the north.

Signs read: “Bibi (Netanyahu) you are not a King, This is a Democracy.”

But the speaker who drew the most applause was Mr. Odeh, the Arab lawmaker whose sarcastic comments about Mr. Netanyahu’s “offer” went viral here. He called for an Arab-Jewish alliance to save Israeli democracy. Historically, Arab parties have never been included in a government coalition, but a vocal minority is now calling for that to change.

Sigal, a protester who wanted to be identified only by her first name, surveyed the crowd, saying, “I am not the only one who is worried. This is beyond politics.”

Canada’s indigenous try to break vicious cycle tearing families apart

For generations, Native Canadians’ own government treated them with appalling cruelty. So today, they are speaking out, making changes to a foster-care system they say perpetuates old problems and thinking.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Although Canada’s indigenous population has more visibility in Canadian political and cultural life than America’s, colonial policies have a dark history here. Traumas from earlier assimilation policies have generated a vicious cycle: Generational issues often see indigenous children born into more precarious family lives, yet those families become victims of a child-welfare system built on centuries of stigma and bias.

In British Columbia last year, of all children “apprehended” at birth – in which the government takes children from their mothers as a last-resort protection – 55% were indigenous. In the 2016 census, 5.9% of the province’s population identified as aboriginal.

Authorities at the top recognize the challenge, but the indigenous community says it’s not enough. It is taking action now, helping to reclaim traditional cultural and family practices to try to break the cycle. A key feature is peer support by other indigenous women who have fought to reunite their families. “It’s more about how we walk with you. And we call it companion care,” says Patricia Dawn, founder of the Red Willow Womyn’s Society. “It’s returning to and honoring that everybody has the right to dignity and respect.”

Canada’s indigenous try to break vicious cycle tearing families apart

Joe Norris, at 81, still wakes up with blood on his pillow some mornings, the result of a blow to the ear that he received as a boy for speaking his indigenous language at the residential school where so many of his generation were sent.

The stain represents the violence of forcefully being taken away from his family to a boarding school intended to assimilate indigenous peoples. But it also represents the bonds to his grandfather, who brought him home and taught him the language, customs, and culture of his Halalt First Nation on Vancouver Island.

“I’m glad he did. I don’t think I would have made it at that school; it would have killed me,” says Mr. Norris, a hereditary chief and retired businessman.

Today he is playing the role his grandfather did for him, as an elder working with the Red Willow Womyn’s Society in the Cowichan Valley, a grassroots network working to stop “child apprehensions,” in which the government takes children from their mothers as a last-resort protection, the government maintains, of the children. The practice disproportionately affects indigenous families. “What we’re looking at is to reclaim our culture, our language, our teachings as a native people.”

Although Canada’s indigenous population has more visibility in Canadian political and cultural life than America’s, colonial policies have a dark history here. Traumas from assimilation policies from the 19th and 20th centuries have generated a lasting vicious cycle: Generational issues often see indigenous children born into more precarious family lives, yet those families become victims of a child-welfare system built on centuries of stigma and bias. In British Columbia last year, of all children apprehended at birth, 55% were indigenous, according to provincial government data. In the 2016 census, 5.9% of the province’s population identified as aboriginal.

Authorities at the top recognize the challenge, but members of the indigenous community, from grassroots activists to elders to doulas, say it’s not enough. They are taking action now, helping to reclaim traditional cultural and family practices to try to break the cycle. “People started saying, ‘This is enough. We are literally falling apart,’” says Marnie Turner, an indigenous doula working in the Vancouver area for indigenous women.

Canada’s residential schools

Canada’s residential school system was established in the 19th century as a network of government-sponsored religious schools, the majority of them Roman Catholic, aimed at assimilating indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society. But according to the 2015 findings of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the establishment and operation of residential schools is best described as “cultural genocide.” An estimated 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children were removed from their homes; the last school did not close down until 1996. (The government formally apologized for the schools in 2008, when it set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.)

In the 20th century, families were split again by what is called the “Sixties Scoop”: mass adoptions of First Nations and Métis children in Canada. And many see disproportionate child apprehensions as the 21st century iteration in the guise of child protective services.

“It’s an echo of residential schools,” says Patricia Dawn, founder of the Red Willow Womyn’s Society, which began a decade ago as a peer support group for indigenous women. “We’re still dealing with this colonial mind, that we’re too drunk. We’re not smart. We need to be helped.”

Canada’s female indigenous population is particularly mistreated, as it has historically been vulnerable to violent and sexual abusers, further tearing families apart. Canada's National Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) released its final report this week, concluding that the disproportionate number of missing or murdered indigenous women over the last several decades is “genocide.”

Katrine Conroy, minister of children and family development in British Columbia, says correcting overrepresentation of indigenous children in foster care – the extent of which she says she was unaware of until becoming minister – has been a top priority since the beginning of her mandate. “I recognize that it’s just not acceptable. This has been going on for too long, and there’s systemwide assumptions and practices that have really failed indigenous kids and families.”

It’s a complex challenge, and removals are only a last resort, she says. The number of apprehensions of indigenous children at birth in British Columbia has gone down by 51 percent in the past decade (from 2008 to 2018), according to the ministry. But she recognizes mistrust toward her office has mounted over decades.

‘We see what you are doing’

Indeed, those on the ground say mainstream prejudices are rife. And few have a better view than doulas like Feona Lim, who coaches white, Asian, and indigenous mothers in Greater Vancouver.

She says she works at the same hospitals and often even with the same staff but sees vastly different attitudes depending on who her client is. “Basically the tone right away it’s like, ‘Oh, you’re having a baby! Congratulations! That must be so exciting’ to ‘When’s the last time you had a drink?’”

She’s part of a burgeoning movement of doulas who are reclaiming traditional birth practices. On a recent evening at the Fraser Region Aboriginal Friendship Centre Association in Surrey in Greater Vancouver, coordinator Corina Bye starts a meeting among doulas. They call themselves the Indigenous Birth Keepers, and they begin with a smudging ceremony using burning sage, tobacco, sweet grass, and cedar and a prayer.

They form part of a network at the Friendship Centre aimed at improving the lives of indigenous families, whether that’s with mothers seeking pre- or postnatal care or by connecting young families to elders for advice. The “wraparound” services, as they are called, are intended to re-create the family supports traditionally found in villages. “We’re just like aunties,” says Ms. Turner of the doulas.

But they are also present on the front lines where separation often happens. “We literally stand,” says Ms. Turner.

Bearing witness is a central part of the work of the Red Willow Womyn’s Society. When an apprehension is anticipated, Ms. Dawn’s telephone rings. Their growing network will make a call to action on social media, placing phone calls and emails to officials and elected leaders, to send the message, she says: “‘We see what you are doing.’ Being called out by your community is an indigenous practice.”

They interrupted four apprehensions last year, says Ms. Dawn.

In some ways, family separation has become more acute. Collette Norris, an elder and Mr. Norris’s cousin, says she struggled with alcoholism while her children were growing up. But her family stepped in to help and keep the kids safe. “They looked after them,” she says. “That’s how it worked. We just loved the kids.”

In today’s climate, she is sure her children would have been taken from her; her granddaughter’s children were taken from her while she was struggling with addiction, and her newborn was removed even after she had recovered. They have since been reunited.

Words of value

Minister Conroy says that her ministry has increased funding in the budget for foster parents, including relatives taking in family, so that children can stay within their communities. That follows legislation that was introduced last year in British Columbia intended to reduce the number of indigenous children in foster care and calls to action nationally from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the first five of which specifically were about child welfare.

But Ms. Dawn says that none of this has been enough, and social workers are not experienced enough with indigenous traumas – and solutions.

The Red Willow Womyn’s Society is now building up prevention work in partnership with the Canadian Mental Health Association in the regional hub, Duncan. In one case, a foster parent housed a mother with her baby instead of separating the two before they moved into temporary housing that is part of a pilot project that provides wraparound services. A key feature is peer support by other indigenous women who have fought to reunite their families. “It’s more about how we walk with you. And we call it companion care,” says Ms. Dawn. “It’s returning to and honoring that everybody has the right to dignity and respect.”

The elders like Mr. Norris play a crucial role in the healing process, she says.

If Mr. Norris’s pillow stands as a sign of the damage wrought upon him, a blanket he has from a residential school is a sign of the power of healing. “When I came out of residential school, my grandfather said that the church, the Catholic Church and government, literally buried our values. And that it’s entirely up to us to dig it up and look at it,” he says. “And there’s holes in our values. So we have patches.”

On those patches are written these words: family values, trust, respect, integrity, love, forgiveness, and responsibility.

“His grandfather told him that residential school had buried the blanket of values and traditions and that his work would be to bring that back,” says Ms. Dawn.

“We’ve been building community through this work and engaging at a community level. And so we’ve been able to birth what we’re calling social protection, because there’s enough of us now in all four directions ... and people are done. We don’t want to do this anymore.”

Conflict closed schools. A teen teaches himself, one toy car at a time.

Nearly 1 million children are out of school in Cameroon as a brutal separatist conflict wears on. Sixteen-year-old Bless is just one. But his irrepressible love of learning underscores how war puts the potential of a generation – and a country – at risk.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Paul Njie Contributor

When Awa Bless Chi fled his hometown, he brought his most prized possessions: a set of electric toy cars. For years, the teenager has been teaching himself to craft the vehicles out of materials at the dump: a plywood tank whose gun barrel swivels 360 degrees and a dump truck that lifts and deposits miniature cargo.

Bless, now 16, dreams of attending university to become an engineer – a dream that was within sight just last year, in his hometown in Cameroon’s North West region. But over the past three years, a conflict between English-speaking separatists, who claim their community has long been marginalized, and the French-dominated government has become increasingly brutal. Bless and his older brother fled to a sister’s home six hours away.

For now, he’s one of the 1 million Cameroonian children out of school. Schools have been frequent targets of separatist violence, seen as symbols of the state. After Bless started displaying his creations on the street, he’s become a local hit: “the budding engineer.” But as flattered as he is, he can’t help but think of what’s missing: to be back in school, figuring out the science behind what makes each little vehicle go.

Conflict closed schools. A teen teaches himself, one toy car at a time.

When separatist violence forced 16-year-old Awa Bless Chi to flee his home in Cameroon’s North West region earlier this year, there were many things he had to leave behind.

He couldn’t take the drawing board or working table where he’d spent long hours teaching himself engineering by building motors for toy cars. And he had to leave the well-thumbed schoolbooks that clued him in to the science behind it.

Then there were the people he loved: his recently widowed mother; the aunt, uncle, and cousins who’d helped raise him; a group of childhood friends.

But there was one cherished thing Bless could take. His electric toy cars – each of which he had built himself with materials from the dump. There was the plywood tank whose gun barrel swiveled 360 degrees, a dump truck that could lift and deposit cargo, a wooden bulldozer that pushed soil and rubble into tiny, tidy piles.

He packed each carefully into cartons, and hoped the driver of the minibus taking him from Nancho to the city of Douala would be careful. On every bump in the cratered road, he held his breath, praying his most prized possessions would arrive intact.

Three years into a conflict that hollowed out his hometown and forced him to quit school, Bless became one of nearly 500,000 Cameroonians who the United Nations estimates have been displaced by fighting between the largely French-speaking government and armed groups from its English-speaking minority, who are calling for independence.

In many ways, Bless knew, he was lucky. In his English-speaking hometown, he hadn’t been kidnapped from school, or beaten by separatist militants, or seen his house burned down by government forces, as other Anglophone Cameroonians had. And he had a place to go – a sister and brother-in-law living in the Littoral region, a French-speaking area outside the conflict zone.

Still, the move was jarring. Until late 2016, Bless had been on track to earn a place at university, dreaming of a career in engineering. Now he was a teenager with no degree, no job prospects, and no idea when he’d go home.

All he had left were his cars.

Cameroon’s rich diversity is a point of pride. “All Africa in one country,” English speakers say, alluding to the country’s mountains and beaches, its deserts and its rainforests. “L’Afrique en miniature,” French speakers boast of the country’s 240-some ethnic groups.

But bilingualism – the country was stitched together from a former British colony and a former French one – has also long been a source of tension. Although French and English are supposed to enjoy equal status, the Francophone majority has dominated politics and society since independence.

In late 2016, lawyers and teachers in the two English-speaking regions began to protest, calling the appointment of a large number of French speakers to their courts and schools a sign of marginalization. By the end of the year, police and army response to the protests had turned violent, and the following fall, an entity calling itself Ambazonia declared it was seceding.

Bless’ own teachers joined the protests, leaving students without any clear sense of when they could return to class. And then, when the strikes ended in February 2017, a new threat rushed in.

From the earliest days of the conflict, schools were seen by “Amba Boys,” as the mostly young and male Anglophone separatists are known, as a symbol of state control. So to clear the way for their new country, they began to burn them to the ground, kidnapping hundreds of staff and students.

“I left school because when you go to school, you’d be attacked, so we were afraid to go,” Bless says. What’s more, “The frequent military patrol at the junction around our school made us to be afraid because each time they were in that area, they’d shoot randomly in the air.”

Indeed, it was increasingly unsafe to go much of anywhere in Nancho, where he lived with an aunt and uncle. So he stayed home, quietly assembling toy cars from a tangle of wires, old motherboards, batteries, and scrap wood, plastic, and metal he’d skimmed from a local garbage dump.

It was a hobby he’d started when he was 8 years old, envious of other children around town.

“I was just playing as a child, and decided to try making my own toys, because my parents couldn’t afford to buy me real toys during Christmas, like other parents did for their kids,” Bless says. He learned the basics from local mechanics and his older brother Derick, who had studied car mechanics in school. The rest he picked up wherever he could.

In 2017 and 2018, the crisis’s brutality escalated on both sides. Ambazonian separatists attacked at least 42 schools between February 2017 and May 2018, according to Amnesty International, and killed 44 soldiers. Government troops, meanwhile, have been accused of torching entire Anglophone villages, torturing and arbitrarily detaining suspected separatists, and killing civilians.

Nearly 1 million children are now out of school across the country, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council – which experts say will carry consequences even after the conflict ends.

“There are [now] children who’ve been out of school for three years,” says Ayah Ayah Abine, president of the Ayah Foundation, a Cameroonian nonprofit that works with people displaced by the crisis. “It will take a miracle to fill that gap.”

At Bless’ home, meanwhile, things weren’t going well. His father had severe heart problems, and in August 2018, he died. Not long after, the family made a difficult decision. With the conflict refusing to ebb, it seemed unlikely the boys would go back to the local school anytime soon. So they went to live with their older sister Edith in Douala, a six-hour bus ride away. Derick went first, and Bless followed a few months later, in March.

In many ways, their new city was a rude shock. Kilomètre Cinq, the neighborhood where Edith, her husband, and nine other relatives shared a house, was crowded and gritty. Sewage gurgled up from broken drains, and mosquitos ducked and dived. On Bless’ first day, a street child snatched his cellphone out of his hand.

Nothing, however, felt more foreign than the language. Douala lived and breathed in French, which Bless barely spoke.

So he went back to what he knew. Inside the walls of his family compound, he tended to his cars, fixing nicks and dents and working on their wiring.

Originally, he planned to display his cars at the school his brother attended. But school authorities refused, he says, so he began simply lining his cars up outside his sister’s house, demonstrating how they worked to passersby and collecting donations in an old plastic bowl.

His street show was a hit, and local media wrote features on “L’ingenieur en herbe,” the budding engineer. But as flattered as Bless is, he can’t help but think of what he’s missing. He longs to be back in school, copying equations and studying technical drawing, his favorite topic. And he dreams of eventually going abroad to study. He missed the enrollment window this school year, but hopes to be back in secondary school before the end of 2019.

In the meantime, he hopes the conflict will end.

“I feel very bad because our own town is being destroyed,” he says. “I don’t support any of them [military nor separatists] because all of them always commit crimes.”

Each time he finishes a new car, he writes the same phrase in careful script across the body. It was true when he was home in the Anglophone North West, and true now that he lives far away in Douala.

Made in Cameroon.

Watch

‘My first mission was Normandy’: World War II pilots recall role in history

A 75th-anniversary reenactment of D-Day is about more than history or getting to fly in cool planes. As a pilot says, it’s about “why we live free, and the sacrifices that were made, and the incredible examples of what we can accomplish as a country when we all come together.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Lt. Col. Dave Hamilton is dressed in a rumpled vintage uniform, but his memory is more than crisp. “I’ll be 97 in July – I’m a kid!”

He played a special role during D-Day as a 21-year-old pilot about to fly his first combat mission: Even before the main airborne assault, the kid from New York was part of an elite squadron of C-47s that left six hours before the main invasion, a squadron of 20 planes that dropped specialized “pathfinder” troops behind enemy lines.

What was it like to be sitting there in the cockpit, waiting to take off?

He pauses. “Maybe the word fear had never entered our minds, but we were anxious,” he says. “And we had our lives and the paratroopers’ lives in our hands – until we dumped them out over France, and so it was somewhat of a relief to get rid of them,” he says, kidding. “I dropped my paratroopers at 15 minutes past 1 o’clock in the morning.”

He went on to fly dozens more combat missions, including in the Korean War, when he flew more than 50 missions in an RB-26 bomber. Later, he trained to fly jets and served in the Air Defense Command, retiring from the Air Force in 1963.

“But I wasn’t sure I was going to live through that first one,” he says. “I came back with over 200 bullet holes in that aeroplane.”

‘My first mission was Normandy’: World War II pilots recall role in history

They’re not as spry as they were 75 years ago when they were aggressive young pilots gearing up for combat during World War II. But today they’re beaming, lost in memory, two old warriors swapping stories only few today know firsthand.

Retired Capt. Peter Goutiere, now 104, and retired Lt. Col. Dave Hamilton, 96, are still standing straight, as if at attention, and almost giddy as they recount their first missions flying C-47 Dakotas, the twin-engine military transports they called “Daks” back then.

“The C-47 was a luxury aeroplane. It had everything,” Captain Goutiere says to me and a small group gathered at a hanger at Waterbury-Oxford Airport in Connecticut. In 1944, during his training in Miami, he was almost mesmerized when he saw the Dak he was to fly to Europe and beyond.

“Here comes this lovely aeroplane,” he recalls, describing the military version of the venerable Douglas DC-3, which helped revolutionize civilian travel in the 1930s. “It had its military insignia on it, and that was my aeroplane,” he says, just slightly jutting his chin with a pursed smile. “By the way, with this old age, I’m deaf as a whatever,” the brash centenarian adds, tapping his hearing aid.

Outside, there’s a regimented fleet of nearly a dozen restored C-47s lined up along the small airstrip this morning, not unlike that time in 1944. These vintage aircraft are part of The D-Day Squadron, a “flying museum” supported by the Tunison Foundation, the nonprofit that helped reboot these WWII-era transports to honor pilots and other WWII veterans like Captain Goutiere and Lieutenant. Cololnel Hamilton – and the roles they played in one of the most significant dates in modern history.

On June 6, this squadron will comprise the American contingent of a massive reenactment of D-Day called “Daks over Normandy,” a multination commemoration that will include dozens of restored C-47s and hundreds of volunteer paratroopers. Each will be wearing not only authentic WWII-era uniforms and gear, but also the same kind of parachutes Allied soldiers used when tens of thousands jumped over occupied France 75 years ago.

Along with others, including the Monitor’s director of photography, Alfredo Sosa, I’ve come to participate in one of The D-Day Squadron’s training runs along the Housatonic River in Connecticut, and I’m feeling a little lucky.

We’ve been assigned to fly with the crew of “That’s All, Brother,” the original lead plane in the first wave of C-47s to fly over Normandy during D-Day’s main airborne assault. Its name intended to be a message to Hitler, this plane was also the first to drop American paratroopers during the massive main invasion – members of the 2nd Battalion of the storied 101st Airborne Division.

This made it feel like more than a historical artifact – part of the point of bringing these aircraft back to life and outfitting their crews with the gear of a bygone era. The goal: Somehow, to make memory alive, to reimprint those breathless moments, to revisit the bravery, the sacrifices.

‘I was No. 14.’

Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton is dressed in a rumpled vintage uniform, but his memory is more than crisp, even now, at 96. “I’ll be 97 in July – I’m a kid!”

He played a special role during D-Day as a 21-year-old pilot about to fly his first combat mission: Even before the main airborne assault, the kid from New York City was part of an elite squadron of C-47s that left six hours before the main invasion, a squadron of 20 planes that dropped the first specialized “pathfinder” troops behind enemy lines.

Wait. You were the very first pilot to fly over Normandy on D-Day? I asked, incredulous. “I was No. 14,” he says. “I flew on the right wing of Capt. Pete Minor, who was an experienced pilot from North Africa. I was brand new from the States. My first mission was Normandy.”

What was like to be sitting there in the cockpit, waiting to take off?

He pauses. “Maybe the word fear had never entered our minds, but we were anxious,” he says. “And we had our lives and the paratroopers’ lives in our hands – until we dumped them out over France, and so it was somewhat of a relief to get rid of them,” he says with a smirk. “I dropped my paratroopers at 15 minutes past 1 o’clock in the morning.”

“But we knew those guys by their first names, family’s and children’s names, everything,” he says, more seriously, describing how every pilot had trained for months with the same group of about two dozen elite Pathfinder soldiers at Bottesford Base in England. “It was a very personal situation, and it meant quite a bit as far as the companionship and the comradeship that we had.”

“Were we anxious? Yes,” Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton says. “Scared? No.”

The 96-year-old pilot was not without bravado, either, as he recalls those first moments. “We were practicing in a three-ship formation,” he says. “I had come from a troop carrier group training in the States, where we had 40-ship to 1,500-ship formations. So a three-ship formation forming a small group of 20 going from England to France? It was a snap. We just made one circle over the field and headed out.”

He returned that morning and went on to fly dozens more combat missions, including in the Korean War, when he flew more than 50 missions in an RB-26 bomber. (“I liked them a lot. They were faster than C-47s, and they had guns!”) Later, he trained to fly jets and served in the Air Defense Command, retiring from the Air Force in 1963.

“But I wasn’t sure I was going to live through that first one,” Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton says of his D-Day mission. “I came back with over 200 bullet holes in that aeroplane.”

‘That’s All, Brother’

About an hour later, Judge Matthew Jalowiec is standing with me next to “That’s All, Brother,” and we’re waiting to climb aboard as the crew of this historic C-47 makes last minute preparations for today’s training run.

A probate judge who serves the nearby towns of Cheshire and Southington in Connecticut, Judge Jalowiec is a self-described “history buff” who has participated in a number of historical reenactments. Today he’s dressed in the vintage WWII paratrooper gear that he’ll be wearing when he participates in “Daks Over Normandy” and makes a commemorative jump with about 300 others.

“It definitely takes it to the next level, because, you know, you can buy the gear, you can dress up, and you can look like it, but when you’re in that plane going 150 miles an hour, at 1,500 feet off the ground, and the light turns green and the jumpmaster is giving you the go command – now it’s not fake anymore,” he says.

He’d never jumped out of a plane before, he says, but for each of past three years he’s been taking a few weeks to train in Oklahoma as member of the Commemorative Air Force (CAF), the organization that flies and maintains the C-47s of The D-Day Squadron – just a part of the 170 refurbished military aircraft they keep in locations across the country as “the largest flight museum in the world.”

Judge Jalowiec has been training for a particular drop zone. He’ll follow the original flight path Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton took 75 years ago and reenact the Pathfinder mission that dropped soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division over the small town of Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, which is just three miles inland from Utah Beach, code name for one of the beachheads where the Allies made a major amphibious assault.

“That was actually the first area liberated on D-Day,” the history buff says, explaining how these paratroopers were tasked with securing the town and clearing a passage for the troops landing at Utah Beach.

“And one of the guys in our group that’s gonna go, his dad jumped in that area,” he says. “So when we jump, you know, we’re jumping with the memory of his dad, there in the same place where his dad jumped 75 years ago. So it’s going to be quite a feather in our cap,” he says with the same giddiness of – well, of a centenarian pilot.

Down the airstrip, Howie Ramshorn is pretty energetic too. Standing on a ladder under the propellers of “D-Day Doll,” another original WWII transport, he’s dressed in an old-school mechanic’s overalls and checking the C-47’s engines before she joins the three-ship formation on this morning’s training run.

A former mechanic and crew chief at TWA for nearly 40 years, Mr. Ramshorn has been volunteering for the CAF since 2010.

“I was born in 1939, and I remember my dad being an air raid warden; I remember the blackouts, the coupon books,” Mr. Ramshorn says, recalling his childhood in Long Island. “So in my little job here, if I can turn around and keep their legacy going, I’m proud to do it.”

Before we climb aboard “That’s All, Brother,” the pilot, Doug Rozendaal, gathers us together to give us an idea of what to expect during this 45-minute flight.

“There’s puffy clouds today, and we’re gonna be below these clouds, so it’s going to be rough,” says Mr. Rozendaal, an experienced commercial pilot. But then he reminds us why we’ll be flying in formation over the Housatonic River on this bright and puffy-clouded day.

“We fly these airplanes as a tool to tell a story, and the story is why we live free, and the sacrifices that were made, and the incredible examples of what we can accomplish as a country when we all come together,” he tells us.

Then he stops to point at the door on the side of the plane – we’ll have to use a rope to pull ourselves up to the flipped-down steps, which are about three feet off the ground.

“What we want to impress on people is to remember, that across that threshold of that door, you know, kids walked out into the deep dark night on June 6,” Mr. Rozendaal says.

There are about 30 stainless steel seats lined up along the sides of the pea-green cabin, each with thick military-style belts. The cabin isn’t pressurized, and as we take off, the roar of the engines and propellers on each wing is deafening. I notice two unopened boxes marked “parachutes” on the floor.

Just like the main airborne assault on D-Day, we’re the lead plane. Outside the window, “D-Day Doll” and another ship called “Placid Lassie” are flying off our wings.

“Man, if you were on the wing, you could probably jump right on those other planes!” one of the other guests says, surprised at how close the three planes were flying together.

We were flying on a bright, gorgeous day with sunshine and blue skies, and as my editor would later point out, the Connecticut countryside kinda looked like France. But the young soldiers in this cabin 75 years ago were sitting in total darkness as they flew across the English Channel.

“You look at their pictures and you say, well, they’re 18, 19 years old, and they were jumping out of a plane that’s taking anti-aircraft fire,” says Judge Jalowiec, who’s looked at a lot of them. “They’re going to get on the ground, and there’s guys who want to kill them. We’re in beautiful sunny weather, and nobody’s going to kill us.”

“But it changes your life forever, once you go out that door,” continues the father of three, musing on the dozens of jumps he’s already taken out of “That’s All, Brother” and other C-47s.

‘The Himalayan Rogue’

We’re in the air less than an hour before we land back at Waterbury-Oxford Airport. In a few days, The D-Day Squadron will make another training run, this time in full formation over the Hudson River to New York, where it will circle the Statue of Liberty.

Then it will embark on the trans-Atlantic trip to “cross the pond” to England, stopping to refuel at Goose Bay, Canada; Narsarsuaq, Greenland; Reykjavik, Iceland; and Prestwick, Scotland, before joining the international contingents of Daks that will reenact the D-Day invasion of Normandy, France.

Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton will also be making this cross-Atlantic flight and then relive his first combat flight 75 years ago. A 95-year-old British paratrooper named Harry Read will also be reliving his jump “into the deep, dark night” on June 6, 1944.

Captain Goutiere didn’t fly a mission during D-Day, but as a pilot known as “the Himalayan Rogue,” he flew an astonishing 680 missions over “the Hump” during WWII, one of the most notoriously deadly supply routes over China, Burma, and India. Pilots also called this flight path the “Aluminum Trail,” since more than 600 planes and 1,000 men were lost.

Captain Goutiere still remembers his first flight over the Hump – and a special moment he took as he flew over Agra, India, the location of the Taj Mahal.

“There was a little building across it on the Ganges River – and for your information, I was born and raised in India – and this building on the Ganges River, that is where I lived when I was 5 or 6 years old,” he tells us.

“So I got permission to circle around my village, that building that I once lived in so long ago, and where my father died,” the 104-year-old pilot says, welling with emotion.

“Then I saluted my wings, for my father.”

D-Day anniversary flight over Normandy

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Redefining the future for capitalism

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

This summer, the federal agency that regulates Wall Street will take a farsighted move. It will hold a public “roundtable” to gather ideas on how to deal with short-term thinking in capital markets. Too many companies, says the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, need to “foster a longer-term” perspective.

While financial experts differ on whether short-termism is getting worse, it is clear that many of today’s problems, from climate change to global migration to aging societies, are so big and difficult that they require companies to resist investor pressure to give short shrift to the long view.

Over the centuries, capitalism has contributed much to the universal welfare. The SEC now wonders if new regulations to discourage short-term thinking might improve that record. Specifically, the agency might allow companies to provide financial data only every six months instead of the current three months.

The demand for a change is certainly there. According to SEC Chairman Jay Clayton, Americans who are building a retirement kitty in 401(k)s and IRAs want to know if their money will produce steady income over decades.

This summer’s roundtable will be an excellent forum to discover better ways to bring foresight and patience into American companies.

Redefining the future for capitalism

This summer, the federal agency that regulates Wall Street will take a farsighted move. It will hold a public “roundtable” to gather ideas on how to deal with short-term thinking in capital markets. Too many companies, says the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, need to “foster a longer-term” perspective.

The SEC is hardly alone in its concern. Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the two front-runners in the presidential contest, have each argued that something must be done about “short-termism.” That term describes a tendency among transient investors to demand profits each quarter from companies, a practice that treats the stock market like a casino or a get-rich-quick lottery.

While financial experts differ on whether short-termism is getting worse, it is clear that many of today’s problems, from climate change to global migration to aging societies, are so big and difficult that they require companies to resist investor pressure to give short shrift to the long view.

Over the centuries, capitalism has contributed much to the universal welfare. The SEC now wonders if new regulations to discourage short-term thinking might improve that record. Specifically, the agency might allow companies to provide financial data only every six months instead of the current three months. It might encourage a company not to predict profits for the coming quarter. And the SEC might look at ways to encourage executive compensation that rewards results based on decadeslong goals. A company could focus on whether its leaders have invested well in employee training, research of new products and services, and activities that help sustain society and the planet.

The demand for a change is certainly there. According to SEC Chairman Jay Clayton, Americans who are building a retirement kitty in 401(k)s and IRAs want to know if their money will produce steady income over decades. “An undue focus on short-term results among companies may lead to inefficient allocation of capital, reduce long-term returns for Main Street investors, and encumber economic growth,” Mr. Clayton says.

One tactic used by many companies is to write a mission statement that defines a purpose beyond profits. This recognizes that a firm must give back to society, which provides the order and market for a company to provide value to shareholders. This summer’s SEC roundtable will be an excellent forum to discover better ways to bring foresight and patience into American companies.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Cleaning up our ‘issues’ through Christ

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Shelly Richardson

Drawing on her experience as a teacher in an educational program for migrants, today’s contributor shares how self-righteousness, pride, and other elements that would keep us from helping to better the world can be healed.

Cleaning up our ‘issues’ through Christ

Ann Atwater, an African American grassroots activist and subject of the movie “The Best of Enemies,” found herself in 1971 as the co-chair of a 10-day series of meetings in Durham, North Carolina, with the goal of reducing school violence and ensuring peaceful school desegregation. Her partner in doing this would be none other than the local president of the Ku Klux Klan, C.P. Ellis.

As you might expect, at first both Atwater and Ellis were pitted against each other, each openly expressing their contempt and hatred for the other’s race. But as they realized what they each had in common – mainly a deep desire for a school system that was safe and peaceful for children – they learned how to put their differences aside and work together. The unlikely duo became lasting friends, bringing the beginnings of reconciliation to their community while at the same time experiencing a softening of their own hearts.

In an interview, Ann, a devout Christian, referred to the healing of the woman with “an issue of blood” in the Bible: “The lady with the issue of blood, she said if she could just touch but the hem of [Jesus’] garment, she believed she would be made whole, and she was made whole. And so many of us have different issues, and if we could just clean up our issues, then we’d be better off” (“Meet the Real Ann Atwater from ‘The Best of Enemies,’” youtube.com/watch?v=emR_N7yLVbU).

What are the issues humanity faces today? Hatred, pride, division, immorality, selfishness, etc., to name a few. How do we clean them up? For the woman with an issue of blood who had been ill for 12 years and whose life seemed hopeless, the healing of her condition was gained by seeking out Jesus. Her deep desire to be healed impelled her to push through the crowds surrounding Jesus and touch his garment. The Bible says that “immediately her issue of blood stanched.” Her thought had been touched by the Christ, and she became a new person, completely healed (see Luke 8:43–48).

While our issues might not be as debilitating as the woman’s in the Bible and while we might not find ourselves in as dramatic a situation as Ann Atwater’s, none of us are without a need to push through the “crowds” of resistance that would keep us out of reach of the Christ and from being an influence for good in the world. We find Christ as we love our neighbor more, express more compassion and understanding, and assimilate more of the Christliness that is so needed in order for healing to take place in the world. “He that touches the hem of Christ’s robe and masters his mortal beliefs, animality, and hate, rejoices in the proof of healing, – in a sweet and certain sense that God is Love” writes the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 569).

Many years ago I was teaching high school English to migrant students in a rural part of Oregon. The program was growing at an outstanding pace, but a new principal became increasingly afraid of potential gang activity. He implemented regulations to exclude from the program those students who did not live with their legal parents. Some of my students who lived in the stable homes of aunts and uncles while their parents migrated were asked to leave school. I tried reasoning with the principal, but he refused to budge. I had to struggle with my own issue of self-righteousness as I viewed this man as racist and narrow-minded.

One day, alone in my classroom, I turned to God with my whole heart for an answer. I needed to feel the power of Christ breaking through my resistance to loving this man who seemed so unlovable. As I reached out humbly, I felt the presence of peace. My “issue” of pride washed away. I knew this man was a child of God – fearless, honest, good, and sincere. I also knew that the Christ-influence opens our eyes to divine possibilities of good that can meet all needs.

I felt led to open the drawer of my desk, and there I saw the business card of someone who worked with migrant students. I never noticed the card before and called the person to ask some questions. This person ended up reaching out to the principal. The next day when I went into work, I was told that the regulations were reversed, as the principal was offered effective alternative ways to curb gang activity and happily implemented those instead. There weren’t any bad feelings. Later, when a dispute came up with one of my students about grades, the principal backed me up 100 percent.

No one is excluded from discovering Christ and entering into his or her own spiritual ministry for good. Fear, indifference, anger, impatience, stubborn narrow-mindedness, intolerance, opinionated beliefs – all of these issues melt as we seek and embrace the tender presence of Christ.

A message of love

Buckle up

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we ask the eternal question: Does the world really need another “Pride & Prejudice” remake? In the case of the novel “Ayesha at Last,” yes.