- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- 2020 race: The one thing 23 Democrats aren’t talking about

- Are US tariffs pushing China and Russia together?

- On D-Day, one Native American is left standing for the hundreds who fought

- At stake in Huawei’s German bid, economic gain vs. national security

- ‘Pride and Prejudice,’ eh? What if Jane Austen were Muslim Canadian?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

D-Day commemoration: A day that transcends politics

Each year they arrive at Normandy: the veterans who pushed back German platoons after landing in the largest seaborne invasion in history. Townspeople hang out of their windows waving American flags. Commemorating the anniversary of D-Day always has a way of transcending politics.

On the 70th anniversary in 2014, which I covered as the Monitor's Paris bureau chief, the unthinkable had happened: Russia had annexed Crimea, Europe’s first forced border exchange in decades. Yet I saw Europe’s leaders standing together, alongside President Barack Obama and Russian President Vladimir Putin, resolute in paying homage to the men whose bravery helped forge a more stable world.

Five years later, the unthinkable is happening again, with the very alliances born out of D-Day under deep strain. Yet President Donald Trump, who has been sharply critical of the international order, gave a reverential speech at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial where 9,000 U.S. servicemen are buried. "You’re the pride of our nation," he told the veterans. French President Emmanuel Macron also thanked the United States, which he said “is never greater than when it is fighting for the freedom of others.”

These words resonate even more powerfully in the presence of the last witnesses of world war. I remember meeting Joe Steimel, who was 19 years old when he landed in Normandy, serving in the 29th U.S. Infantry Division. He still carried the weight and ambiguities of war. “I want to say to the French,” he told me, tearing up, “if I killed any civilians, I am truly sorry.”

For a bonus read, we have dusted off a personal essay from our archives. Monitor diplomacy correspondent Howard LaFranchi reflects on his experience as a high school exchange student, living with former members of the French Resistance.

Now to our five stories for today.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

2020 race: The one thing 23 Democrats aren’t talking about

Can U.S. foreign policy be a winning campaign issue? Republicans have traditionally had an advantage on national security, but Democratic dark horse Seth Moulton wants to flip that script in the 2020 race.

Is the presidential race still about choosing the next leader of the free world? If so, there’s remarkably little discussion of the world in the 2020 race so far. Despite polls showing that nearly 6 in 10 voters believe President Donald Trump has made America less respected in the world, the candidate most directly challenging him on foreign policy is 40-year-old dark horse Seth Moulton, a third-term congressman from Massachusetts.

As the Trump administration appears to edge toward conflict with Iran, Representative Moulton, a decorated Marine who served four combat tours, says it’s clear the U.S. hasn’t learned the lessons of Iraq. “If people who have seen the worst of war don’t stand up and do these jobs in Washington, then people in Washington are going to keep doing this,” says Mr. Moulton, who maintains Democrats should quit ceding patriotism to Republicans. “I think we have a historic opportunity to reclaim the mantle of leadership on national security.”

But with a week before the June 12 deadline, he has yet to meet the 65,000-donor threshold required to enter the first Democratic debate and advance his ideas.

2020 race: The one thing 23 Democrats aren’t talking about

Of all the Democrats vying to be leader of the free world, Seth Moulton may be the only one who actually talks much about the world.

An ex-Marine who served four combat tours in Iraq, Representative Moulton of Massachusetts has tried to stand out in the crowded field of Democratic presidential candidates by emphasizing military and foreign-policy issues. He says it’s important for his party to highlight the hash President Donald Trump has made of the U.S. global role by alienating allies and embracing authoritarians.

“I think we have a historic opportunity to reclaim the mantle of leadership on national security,” he says between campaign stops in New Hampshire in which he calls for Democrats to quit ceding patriotism to Republicans. “I don’t know why so many Democrats are passing it up, but I’m not going to pass it up.”

Let Joe Biden emphasize electability. Bernie Sanders can talk about corporate power all he wants. While Kamala Harris and the rest of the field debate the fine points of expanding health care, Mr. Moulton says he is focused on restoring America’s moral authority in the world.

So far he hasn’t gained much traction. Mr. Moulton remains a blip in the polls, far behind the leaders. There may be multiple reasons he has yet to catch fire, but one could be this: Foreign policy is a difficult electoral issue.

Foreign issues seldom sway voters, particularly in primaries. For candidates, they can be tripping hazards best avoided. It’s easy to make a foreign-policy gaffe – mispronouncing a foreign leader’s name, say, or placing their nation on the wrong continent. But it’s hard to get a campaign rally excited by calls to “support the liberal international order.”

Still, 2020 could be different. Mr. Trump’s disruptive approach to foreign policy, from his threats to Iran to his denigration of longtime NATO allies, may indeed have made some voters wary. Fifty-seven percent of likely voters believe Mr. Trump has “made America less respected around the world,” according to a new poll from National Security Action, a Democratic-leaning group. Sixty-seven percent think Mr. Trump “lacks the temperament” to be commander in chief.

Whoever emerges as the Democratic nominee could attack Mr. Trump directly on his record as head of the U.S. armed forces, despite the Republican Party’s customary advantage on security and foreign issues. At a time when Trumpism has shaken up traditional GOP thinking on national security, experts say there is indeed an opportunity for a centrist Democrat to gain political ground.

“When I think about some of the more thoughtful people over the last 20 years on the Republican side on how to manage irregular threats, and to think about emerging peer competitors, those voices are gone,” says Richard Shultz, director of the International Security Studies Program at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in Medford, Massachusetts. “So you have the president, whose foreign policy is chaotic, and you have [national security] documents that are drafted that to me are challengeable. ... It’s the kind of argument a Biden could make.”

But former Vice President Biden, who first ran for president when Mr. Moulton was in elementary school, is not making such arguments. Not yet, at least.

“One of the most striking things about the Democratic primary so far – aside from the sheer number of candidates running – is how little any of them has said about foreign policy,” wrote Jonathan Tepperman, editor of Foreign Policy magazine, last month.

“I think Biden will increasingly step it up,” says David Gergen, a political analyst and professor of public service who taught Mr. Moulton at Harvard Kennedy School. “But Seth right now is one of the only go-to people.”

Pushups on the stump

Mr. Moulton, dressed in his standard campaigning uniform – a blue shirt (no tie) and khaki pants – kicked off a recent Sunday morning with a veterans fundraiser outside Boston. Since he arrived too late to do pushups with the participants, he ended his stump speech with a set of 28, ramrod straight.

“Let’s see Joe Biden do that!” someone shouted.

Mr. Biden, the current Democratic front-runner, may not be much competition in calisthenics, but he has decades more foreign-policy experience and is way ahead in the polls.

Unless Mr. Moulton gets 65,000 donors to give at least $1 to his campaign by June 12, he won’t be allowed to participate in the first couple of debates. And he must double that to make the third debate.

A small crowd of potential donors is waiting for Mr. Moulton when he arrives an hour later at the Black Forest Café in Amherst, famed for its whoopie pies. Some attendees have driven more than an hour to hear him talk about how education, climate change, and immigration are all national security issues, affecting Americans right here at home.

He lambasts Mr. Trump’s foreign policy, pointing to recent events: the president’s “best buddy in North Korea” firing off missiles again, a “failed coup” in Venezuela, a march toward “war with Iran.”

The Trump administration has repeatedly said it is not seeking war. It has justified the current U.S. military buildup as a response to attacks on several oil tankers for which Washington blamed Iran. But the escalation has brought a certain sense of déjà vu for some.

“It’s amazing to me that in this drumroll for war in Iran, we clearly haven’t learned the lessons of Iraq,” says Mr. Moulton, who was awarded the Bronze Star in Iraq. But even while he was still fighting, the young Marine was already becoming disillusioned with what he saw as a misguided military adventure. That eventually led him to run for Congress – and now the presidency.

“If people who have seen the worst of war don’t stand up and do these jobs in Washington, then people in Washington are going to keep doing this,” he says.

Clear eyes about Trump’s support

Many supporters of Mr. Trump praise him for asserting American strength, critics be damned. They see his direct talks with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un as far more promising than the decades of stalemate under previous presidents. They hail him for calling out Iranian aggression in the Middle East, and cheer on his tough trade stance on Beijing after years of watching manufacturing jobs move to China – even if his tariffs hurt U.S. workers.

Mr. Moulton credits the president for confronting China, but disagrees with his approach. Instead of tariffs, he says, the United States should spearhead a Pacific version of NATO and revive something like the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade alliance to counterbalance China, particularly in artificial intelligence.

World leaders like China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin need to start taking the U.S. seriously again, he says, especially with the Kremlin believed to be intent on undermining the 2020 election.

At Mr. Moulton’s fourth and final event of the day, in Londonderry, Vietnam veteran Greg Warner says to him, “The Chinese are playing Go, and they’re very good at it; the Russians are playing chess; and we used to be playing checkers. But now we’ve got a president that plays tic-tac-toe. ... We’re not paying attention! We’re not even playing.”

“You’re absolutely right,” Mr. Moulton responds. “We’re asleep at the switch.”

But the depth of support for Mr. Trump is not lost on Mr. Moulton, who keeps in touch with conservative Marine buddies, works out regularly with Republicans, and travels through Trump country more than most coastal Democrats. He tells every crowd he addresses that it’s going to be a lot harder to beat Mr. Trump than many Democrats think.

For Mr. Moulton, however, the first battle is getting on the Democratic debate stage. Graham Allison, an adviser to presidential administrations for decades who taught Mr. Moulton at Harvard Kennedy School, says he is quite experienced in foreign policy compared with almost all the other candidates and even compared with former presidential candidates – Mr. Trump included.

“I find [his ideas] very solid, sensible, pragmatic – not ideological,” says Professor Allison.

Still, even Mr. Moulton’s former professors say his odds of winning the Democratic nomination are not great. But as his wife said in his kickoff campaign video, once he puts his mind to something, he won’t quit.

“The person that takes on Donald Trump needs to be a tank … and that’s Seth,” said Liz Moulton.

Are US tariffs pushing China and Russia together?

Russia has felt exiled from the West for years, barred by economic sanctions. With China now facing U.S. tariffs and Western suspicions over Huawei, the Kremlin has a potential partner for the future.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

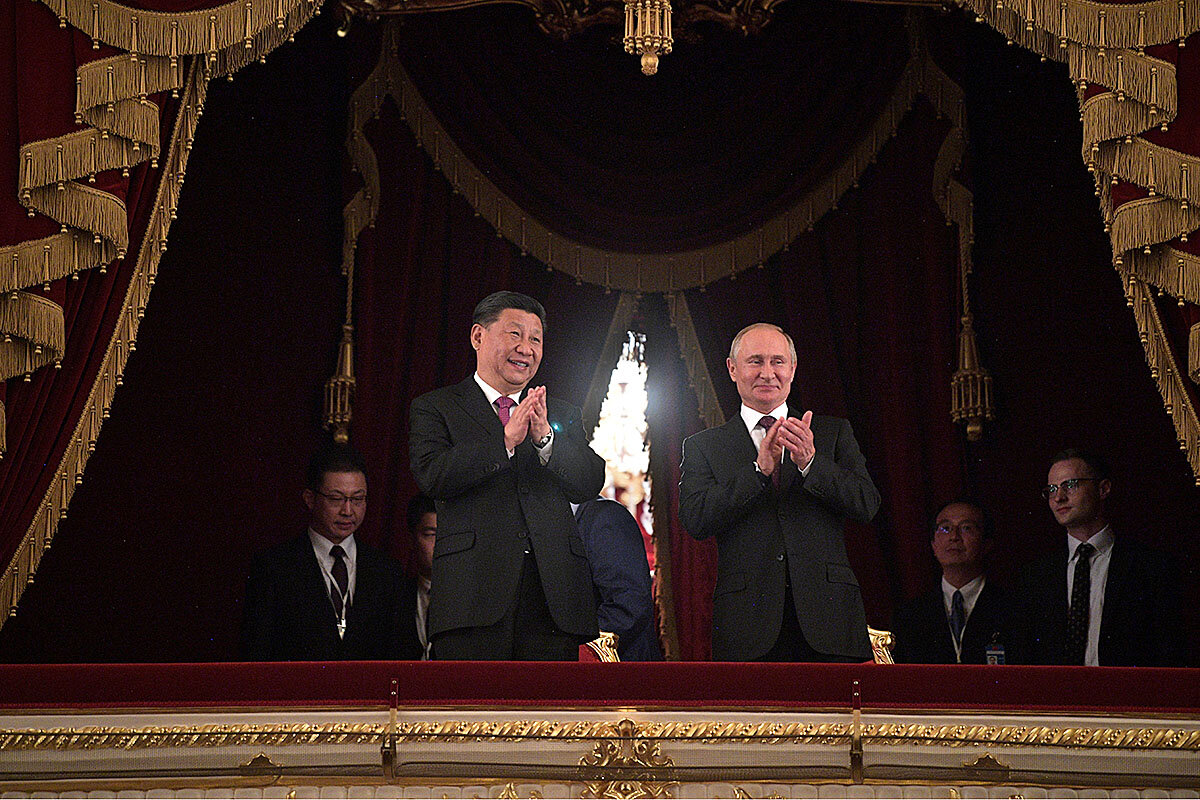

As Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin meet this week, the circumstances could be right to create a breakthrough for economic integration between China and Russia.

Russia has been in the equivalent of a defensive crouch for five years now, since the annexation of Crimea, and has come to view its alienation from the West as a permanent condition. But for China, the U.S. tariffs against Chinese goods and what it sees as a campaign against some of its leading companies, including Huawei, are something quite new.

Now, the roads, high-speed railways, and agricultural enterprises that have been discussed for years may find new impetus. Mr. Putin and Mr. Xi are also likely to discuss carrying out their mutual trade in currencies other than the U.S. dollar. And Russia has recently engaged Huawei to build its 5G infrastructure.

“In both Russia and China, everything is decided by decisions made at the top. If Putin and Xi decide to increase bilateral trade, it will be done,” says Yury Tavrovsky, a China expert in Moscow. “If they want to integrate our financial systems, or invest in Russian infrastructure and agribusiness, that will happen when they say so.”

Are US tariffs pushing China and Russia together?

Call it “panda diplomacy.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping arrived in Russia for a three-day visit and unveiled the loan of two carrot-munching giant pandas for the Moscow Zoo. It was a symbol, he said, of his growing “close personal friendship” with Vladimir Putin.

The charismatic and uniquely Chinese creatures are already wowing Muscovites, who have not had the chance to see a panda up close since Mao Zedong gave one to Nikita Khrushchev back in the 1950s, to cement a similar moment of intense rapprochement between the two Asian giants.

In those days, it was a shared belief in communism that drew them together. Though both remain authoritarian states, the ideologues are long gone and pragmatic technocrats now rule. The dynamic driving them to seek closer integration today is the need to forge a geopolitical common front and hedge their economic bets in the face of escalating hostility, sanctions, and trade war from the West, particularly the United States.

Russia has been in the equivalent of a defensive crouch for five years now, since the annexation of Crimea, and has come to view its alienation from the West as a permanent condition. But for China, the recent piling on of U.S. tariffs against Chinese goods and what it sees as a campaign against some of its leading companies, including Huawei, is something quite new and unnerving. Some experts say that economic integration between Russia and China, which has been the subject of much talk but very little action over the past few years, could be set for a breakthrough.

“The Chinese are calling it a ‘new situation,’” says Yury Tavrovsky, a China expert with Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia in Moscow. “It’s not new for us, but it is for them. The Chinese seem very surprised. They had gotten used to having the doors open for them, being greeted as economic partners in the West, and not being treated as a great threat. Now, suddenly, they are enemy No. 1. The kind of conversation Putin and Xi will be having behind closed doors this week is likely to be different from the past.”

Pushing China and Russia together?

Russia and China have a 2,600 mile border, and a very troubled history that’s been punctuated by periods of intense hostility. Mr. Tavrovsky says many Chinese still resent Russia’s expansion across Asia to the Pacific in past centuries, and see it as having taken place at China’s expense. The two came together in the mid-20th century amid a burst of communist solidarity, but soon fell apart as mutual suspicion and ideological discord took hold. In a major strategic coup, President Richard Nixon traveled to Beijing in 1971 and sealed a deal that effectively split the communist world and brought China into the Western camp against the USSR.

“Now we are looking at a kind of reverse situation unfolding,” says Sergey Karaganov, a senior Russian foreign-policy hand. “The USSR lost, in part, because it had China and the West against it. Now it is Russia and China coming together, with all the vast resources of Eurasia, increasingly in opposition to the West. It’s not a good thing; it’s not the world we would wish for. But it is looking more possible all the time.”

During the Putin era, Russia has settled its long-standing border disputes with China, improved economic cooperation, and established a joint geopolitical playbook that opposes U.S. hegemony and appeals for a multipolar world order in which Russia, China, and other emerging powers would have more say in global institutions. Mr. Putin and Mr. Xi have indeed built a strong personal relationship; the two have met 30 times in the past six years alone.

But the promise of economic integration has not yet materialized. Bilateral trade has grown rapidly, to about $110 billion last year. But that’s a tiny fraction of China’s trade with the West – Russia holds tenth place in China’s list of trading partners – and, despite years of sanctions, barely half of Russia’s trade with the European Union.

Mr. Putin and Mr. Xi will be talking about merging China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative with Russia’s Greater Eurasian Partnership plan for the former Soviet Union, but so far those ideas remain largely on paper. The only big developments are in the energy sector, which will see the $400 billion Power of Siberia gas pipeline come onstream this year. But the roads, high-speed railways, and vast agricultural enterprises that have been discussed for years have yet to materialize.

Mr. Karaganov says there are plans to make Russia a key agricultural supplier for all of Asia by developing the vast unused arable lands of Central Siberia and building transport links to the south, but they will take time.

“Agricultural exports, mostly grain and soybeans, are increasing,” he says. “But this is Russia, these things take time. And we will proceed cautiously. We do not want to develop a one-sided dependence on China. We have been in that position with the West, putting all our eggs in one basket, and no leadership in Moscow is ever going to repeat that mistake.”

If Putin and Xi say it, it will be so

Experts say that Russia and China could step up their military cooperation, which has already seen huge joint war games in the Far East, although they add the prospect of a full-blown military alliance remains remote.

Russia might become a destination for smaller Chinese businesses seeking to avoid U.S. tariffs, some experts say. High-tech cooperation seems set to increase as a result of U.S. pressures as well; this week Huawei signed a deal with the Russian telecommunications giant MTS to develop 5G technology in Russia.

Another thing Mr. Putin and Mr. Xi are likely discussing is dumping the U.S. dollar and carrying out their mutual trade in other currencies. Russian and Chinese leaders have been advocating this step for years, but still carry out most of their own bilateral trade in dollars.

“All these ideas are hampered by ongoing political mistrust between Russian and Chinese elites,” says Mr. Tavrovsky. “In both Russia and China, everything is decided by decisions made at the top. If Putin and Xi decide to increase bilateral trade, it will be done. If they want to integrate our financial systems, or invest in Russian infrastructure and agribusiness, that will happen when they say so.

“This has not happened yet. But if the Chinese conclude that it’s hopeless to fix these problems with the U.S., and they are looking at being permanently blocked in their Western economic relationships, then Russia is likely to be the biggest beneficiary in that situation.”

A letter from

On D-Day, one Native American is left standing for the hundreds who fought

Charles Shay may be the last living Native American World War II veteran who participated in D-Day. His return to the theater of war is a chance to honor the 500 Native American and First Nations soldiers who also served.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Harald E.L. Prins Contributor

-

Bunny McBride Contributor

Spectacular eagle feather staffs and colorful flags were hoisted high as combat veteran Charles Shay, erect and solemn, read aloud the names of the Native American soldiers buried at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. Mr. Shay is one of up to 50,000 North American Indians who served in World War II. As a combat medic, Private Shay treated countless wounded soldiers, including many whom he rescued from drowning in the rising tide on D-Day in 1944.

At this week’s ceremony, traditionally-dressed dancers in beaded moccasins were accompanied by drumming and singing. Flowers were placed and Native American veterans performed a blessing at each headstone, touching it with an eagle feather and sprinkling sacred tobacco at the base.

Mr. Shay is likely the last survivor of the 500 North American Indian warriors who dropped from the night sky or landed on the beaches on D-Day. James Francis, a tribal historian for the Penobscot Indian Nation, of which Mr. Shay is a member, says he’s been thinking about how “Charles especially exemplifies valor. It’s fitting that he is the last Native American veteran on hand to close the D-Day chapter of the biggest war ever fought on the planet.”

On D-Day, one Native American is left standing for the hundreds who fought

The flag of the Penobscot Indian Nation flies above the low dunes at Omaha Beach in Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. At the base of the flagpole stands a sculptured granite turtle. This monument is the focus of a tribute to the 175 Native American soldiers who struggled up this shore on D-Day 75 years ago. On Wednesday, a delegation representing numerous tribal nations gathered here for a commemorative ceremony led by Charles Norman Shay, the World War II combat veteran for whom the small memorial park is named.

“We are gathered here at the turtle monument to ensure that the great sacrifices made by Native American nations in the Second World War are no longer ignored and never forgotten,” Mr. Shay told the large crowd of observers. A 94-year-old elder of the Penobscot Indian Nation in Maine, he was among a total of some 500 American and Canadian Indian soldiers who invaded Normandy in boats, parachutes, and gliders in 1944. Mr. Shay “represents all American Indians well,” says Lanny Asepermy, a Comanche tribal historian and decorated Vietnam War veteran who is here with a delegation of Comanche code talker relatives.

French and American soldiers, including troops of the 1st Infantry Division in which Mr. Shay served, stood at attention at the Charles Shay Indian Memorial. A procession of Native Americans took position, and town Mayor Philippe Laillier spoke movingly about how Mr. Shay, as a young soldier, felt protected on D-Day under the “maternal wing” of his mother’s prayers and the spirit of the turtle’s shell.

The Penobscot veteran was one of up to 50,000 North American Indians who served in World War II. As a 19-year-old combat medic attached to an assault platoon storming Omaha Beach at dawn, Private Shay treated countless wounded soldiers, including many whom he rescued from drowning in the rising tide. For gallantry displayed on the beach that day, he was awarded the Silver Star. He served in subsequent key battles in France, Belgium, and Germany until he was captured after crossing the Rhine just weeks before peace was restored.

After his first pilgrimage back to Omaha Beach 12 years ago, Mr. Shay was inducted into the Legion of Honor by French President Nicolas Sarkozy. Since then, the Penobscot elder has committed himself to drawing attention to sacrifices made by North American Indian soldiers and their communities.

This year, close to 100 Native Americans representing more than 20 tribal communities across the U.S. have descended upon Normandy with Mr. Shay to mark the anniversary of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France. He is a key figure in a dozen Native American commemorative events being held in this week of remembrance.

At an event on Monday, the Penobscot veteran stood at the center of a ceremony at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer. In this 172-acre burial ground, at least 28 of the white marble crosses among more than 9,300 headstones mark the graves of Native Americans who died in the Battle of Normandy, beginning on D-Day.

For this ceremony, some 30 Native American men and women, half of whom served in more recent wars, carried spectacular eagle feather staffs or colorful flags representing their tribes. They hoisted them high as Mr. Shay, erect and solemn, read aloud the names of the Native American soldiers buried here.

Traditionally-dressed women stepped forward in beaded moccasins to perform an historic dance, as Justin Young of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Affiliated Tribes drummed and sang. Then the group moved through the cemetery to place flowers at the 28 Native graves. Several Native American veterans performed a brief blessing at each headstone, touching it with an eagle feather and sprinkling sacred tobacco at its base.

At yet another event, Mr. Shay spoke to a crowd about freedom: “What I do care about is the price of freedom – a simple seven-letter word. Seven is a sacred number in my Penobscot culture, as it is in many Native American traditions and numerous other cultures across the globe. Liberty also has seven letters. These hallowed words represent our inherent dignity and inalienable natural right as human beings, regardless of our race, nationality, or religion. Treasure them, for these precious concepts remind us of great sacrifices and inspire us to remain forever vigilant.”

Among World War II veterans still alive, Mr. Shay is likely the last survivor of the 500 North American Indian warriors who dropped from the night sky or landed on the beaches on D-Day. Commenting on this, Penobscot tribal historian James Francis says, “Looking at the ‘Faith, Purity, Valor’ motto on the Penobscot flag I carried in the Turtle Monument ceremony, I thought how Charles especially exemplifies valor. It’s fitting that he is the last Native American veteran on hand to close the D-Day chapter of the biggest war ever fought on the planet.”

Thursday, Mr. Shay put all the praise he receives into perspective at the major event of the week, presided over by presidents Emmanuel Macron and Donald Trump with an audience of about 12,000. While he and other veterans sat on stage waiting for the presidents to arrive, a short film about D-Day played on several large screens, sending Mr. Shay’s voice across the cemetery: “I am not a hero. I just did my job. The real heroes are laying here in the cemetery. These are our heroes and we should never forget them.”

At stake in Huawei’s German bid, economic gain vs. national security

As Huawei campaigns to build 5G telecommunications infrastructure across the world, Germany must reconcile commercial benefit with national security in granting critical access to the Chinese telecom.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Clifford Coonan Contributor

Inside a former army barracks in March, Germany’s telecoms regulator set a large clock ticking. The country’s multibillion-dollar auction for bandwidth in cutting-edge 5G mobile networks was on. Germany’s three main operators – Deutsche Telekom, Vodafone, and Telefonica – all use equipment from Chinese telecom giant Huawei in their networks. In fact, Huawei has been ensconced in the German telecommunications landscape for decades.

But providing 5G network infrastructure touches a higher level of national security than simple smartphones, which is why the White House announced May 15 that it was barring Huawei from selling its products in the U.S. While Germany is taking a different approach, the tension highlights the challenges the country will face as it tries to balance security with economic competition as it pursues partnerships with Huawei and, by extension, the Chinese government.

“For a long time, the German government and business have operated as if these are two distinct relationships, and they continue to do so,” says Samantha Hoffman, a cyber policy analyst. “Now Germany finds itself in a difficult position where it must deal with the reality that its bilateral trade relationship with China exposes it to national security risk.”

At stake in Huawei’s German bid, economic gain vs. national security

When the White House announced May 15 that it was effectively barring Chinese telecom giant Huawei from selling its products in the United States, it was perhaps the most extreme position taken by a nation against the colossal communications firm.

But the competing interests behind it – national security versus commercial and technological benefit – are being calculated across the West, as countries weigh whether to allow the Chinese firm a role in building their future telecommunications infrastructure.

In Germany, the math came to a very different result – but also highlights the challenges that countries will face as they try to balance security with economic competition as they pursue partnerships with Huawei and, by extension, the Chinese government.

Huawei’s German rise

Inside a former army barracks in March, Germany’s telecoms regulator set a large clock ticking. The country’s multibillion-dollar auction for bandwidth in cutting-edge 5G mobile networks was on.

Germany’s three main operators – Deutsche Telekom, Vodafone, and Telefonica – all use Huawei equipment in their networks. (A fourth company, newcomer 1&1 Drillisch, is also taking place in the auction.)

In fact, Huawei has been ensconced in the German telecommunications landscape for decades. In a story that mirrors China’s metamorphosis into a global power, the company opened its first German office in Eschborn, near Frankfurt, back in 2001.

Four years later it signed its first major contract for DSL technology, and since then it has become a real presence. Revenues in Germany last year were around €2.2 billion ($2.5 billion) and the company now employs 2,500 people. Its Western Europe headquarters has been in Düsseldorf since 2007, and it started selling Huawei-branded smartphones in Germany in 2011.

But providing 5G network infrastructure touches a higher level of national security than simple smartphones. 5G technology will create high-speed links for everything from autonomous vehicles to factories.

German intelligence services argue there are particular risks from the hitherto unseen degree of interconnectedness between 5G and other areas of critical national infrastructure in Germany. It is this concern that prompted the White House action in May. The U.S. argues Huawei is too close to the Chinese government, which could press the company for backdoor access to networks using its technology.

Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei – whose career as a People’s Liberation Army officer is one of the reasons many fear the company is too close to the Beijing government – has responded to Germany’s concerns by saying he would “not do anything to harm mankind.” And Huawei has stressed its role as a good corporate citizen in Germany committed to fulfilling all security criteria that are currently being developed by the government for technology vendors.

“Huawei has established a fruitful working relationship with the Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) and opened a cybersecurity lab in Bonn where cooperation with the BSI on several levels takes place,” says Patrick Berger, Huawei’s head of media affairs for Germany.

‘German economy rises and falls with China’

For Germany, the Huawei problem may indeed be rooted in its integration with China, but not in the espionage risk. Rather, the problem may be that Germany needs China too much.

China was Germany’s most important trading partner for the third consecutive year last year with a total trade volume of €199.3 billion ($225.7 billion). Germany sent exports to China worth €93 billion ($105 billion) in 2018, a rise of 8%.

Germany’s auto firms like Volkswagen and industrial giants have become too dependent on China for economic expansion. Now that it is so deeply invested in its relationship with China, Berlin needs to balance security concerns with trade. As Jörg Krämer of Commerzbank put it: “The German economy rises and falls with China.”

The Chambers of Industry and Commerce estimates some 900,000 jobs in Germany depend on exports to China.

“If technological key competences are lost and if this affects our position in the global economy as a result, this would have dramatic consequences for our way of life, for the state’s ability to act and for its ability to create in almost all areas of politics,” said German Economics Minister Peter Altmaier.

Also, Germany sees the development of 5G technology as crucial to the country’s future as a leading industrial nation.

“If 5G delivers on its promise, it will be the backbone of the ‘internet of things’ infrastructure. This creates dependency,” says a European cybersecurity expert who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of his research in the sector.

“Thus, I would not worry ‘only’ about espionage, I would worry about the larger dependency on Chinese tech, including availability, but also leverage due to the dependency. Thus, the bigger question is how to manage the increasing dependency on the Chinese trade relationship, and what the long-term game in this is.”

Espionage concerns

Nonetheless, concerns about Huawei’s inclusion in the development of 5G infrastructure linger, especially in the intelligence community.

Germany’s foreign intelligence service, the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), has warned the Chinese government could install electronic “backdoors” in Huawei 5G technology for espionage and surveillance and could even use hidden “kill switches” to disable the 5G infrastructure.

Gerhard Schindler, former director of the BND, said most of the risks were because China was not a democratic state, but a strongly authoritarian regime with security organs that can require any companies, even private ones, to supply information if they want it.

“Anyone who installs this technology is also in a position to monitor them,” Mr. Schindler told German radio.

Samantha Hoffman, an analyst at the International Cyber Policy Centre at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, warns the German government would be irresponsible to ignore the BND’s advice.

“One issue is that it seems Germany has bought the Chinese Communist Party’s argument that the bilateral trade relationship can be separated from politics, but the party itself doesn’t separate political and economic issues, so why would it do so in the bilateral relationship with Germany?” says Ms. Hoffman, a former visiting academic fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin.

“For a long time, the German government and business have operated as if these are two distinct relationships, and they continue to do so,” she says. “Now Germany finds itself in a difficult position where it must deal with the reality that its bilateral trade relationship with China exposes it to national security risk.”

“I’m certain that state actors will attempt to compromise 5G networks to enable spying,” says Tom Uren, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. “We’ve seen other telecoms networks at times being used for espionage, and there have been state sponsored groups that have compromised internet routers too. In general telecommunications are attractive to state sponsored intelligence because that is where communications take place.”

“Whether Huawei itself will be pressured to assist is a different question, and is entirely up to the Chinese state,” he adds. “I think Huawei has relatively little ability to resist if the Chinese Communist Party asks. After all, it’s written into Chinese law that they must assist.”

Book review

‘Pride and Prejudice,’ eh? What if Jane Austen were Muslim Canadian?

Who do classic tales belong to? In “Ayesha at Last,” Uzma Jalaluddin brings a Muslim perspective to “Pride and Prejudice.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Toohey Correspondent

Does the world need “Pride and Prejudice and Muslims”? Indeed, it does – at least, it needs Uzma Jalaluddin’s version. Like “Pride and Prejudice,” “Ayesha at Last” is not just about a heroine finding her man, but how she navigates her small community’s narrow expectations for women and her family’s foibles and financial struggles, finding strength in her voice.

“Ayesha at Last” is packaged as chick lit, but the cover is just the book’s mask – and this is a book that’s all about the masks we wear to protect ourselves or please others. Where the novel shines is as “immigrant lit,” painting a nuanced portrait of an immigrant community and exploring themes like the intergenerational conflicts that can arise around tradition and assimilation. These become even more fraught in our current political landscape, with its rising tides of Islamophobia and nationalism. Yet “Ayesha at Last” is light and incandescent and deeply pleasurable from start to finish. You know it’s a good book when it’s obvious from the start who is going to get married, and yet you still can’t stop reading.

Not to mention the humor. From the first to last page, “Ayesha at Last” is very funny.

‘Pride and Prejudice,’ eh? What if Jane Austen were Muslim Canadian?

Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” has given birth to a cottage industry of sequels, variations, and modernizations, from “Bridget Jones’s Diary” or the Bollywood film “Bride and Prejudice,” to “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.” Now comes an update set among Muslim Canadians, “Ayesha at Last,” the debut novel of Uzma Jalaluddin, who writes a humorous advice column on parenting for the Toronto Star.

Does the world need “Pride and Prejudice and Muslims”? Indeed, it does – at least, it needs Jalaluddin’s version, which is full of wit and verve and humor. Like “Pride and Prejudice,” “Ayesha at Last” is not just about a heroine finding her man, but how she navigates her small community’s narrow expectations for women and her family’s foibles and financial struggles, finding strength in her voice.

“Ayesha at Last” is packaged as chick lit, with a silhouetted face with a dash of lipstick, around which swirls a purple hijab on its golden cover, but that’s just the book’s mask – and this is a book that’s all about the masks we wear to protect ourselves or please others. Where the novel shines is as “immigrant lit,” painting a nuanced portrait of an immigrant community and exploring themes like the intergenerational conflicts that can arise around tradition and assimilation. These become even more fraught in our current political landscape, with its rising tides of Islamophobia and nationalism. Yet “Ayesha at Last” is light and incandescent and deeply pleasurable from start to finish. You know it’s a good book when it’s obvious from the start who is going to get married, and yet you still can’t stop reading.

Not to mention the humor. From the first to last page, “Ayesha at Last” is a very funny book.

The plot centers around two South Asian immigrant families, that of Elizabeth and Darcy – oops, I mean Ayesha and Khalid. An observant Muslim, modern in her views of women and marriage, Ayesha is outspoken, creative, loyal, and easily bemused. From a family of modest means – her mother works night shifts as a nurse, while Ayesha substitute teaches – she’s all too aware that at 27, she has aged out of the marriage market, according to "the Aunties."

The key to a “Pride and Prejudice” remake is a dreamy Darcy, and Khalid is dreamy. He doesn’t care what others think, and so he is judged to be proud. He cooks to unwind, but surreptitiously, since his mother believes it’s a woman’s job. Missing his sister, whose absence haunts him, makes him serious. Unflaggingly gentle and loyal to a fault, Khalid’s scrupulous honesty and religious commitment make him socially awkward, especially in the face of sabotage from his Islamophobic boss, Sheila, at his tech firm. Creating a leading man who sports a long beard and robes – an appearance many westerners associate with radicalism – is a radical act, in the best sense of the word. Khalid is a contemporary invisible man, a character onto whom others project their assumptions and preconceptions, even more progressive Muslims like Ayesha. Yet, the story suggests, sometimes those who appear most strange or foreign are most trustworthy, while those who accommodate may merely be slick.

When Khalid spots Ayesha at a lounge and mistakenly assumes she is drinking, he judges her within earshot, before falling in love while watching her perform a poem. Hijinks ensue, propelled by a cast of wonderfully drawn comedic supporting characters. Ayesha’s grandfather, or Nana, a former English professor in Hyderabad, India, speaks largely in Shakespeare quotes. Masood, a wrestler and life coach, courts Ayesha in a clever modernization of the oafish clergyman Mr. Collins, who relentlessly proposes to Elizabeth. Masood, after assuring Ayesha, “I’m just not that into you,” won’t stop texting her. Claire, her best friend, provides support while Hafsa, her shallow cousin, nearly spoils Ayesha’s chance at romance.

Imam Abdul Bari, the wise spiritual guide at the local mosque, is just the sort of clergyman quietly fighting the good fight who all but disappeared from contemporary literature in the 20th century. (As I write this, I saw the minister who runs my local café, and gives all the proceeds to charities, tending to a homeless woman who had fallen asleep on the café sofa. Will someone please write these guys back into our stories?)

In the midst of all this, Jalaluddin touches on topics like alcoholism, homelessness, and internet porn – pressing issues of our times – weaving them in, in a way that feels unforced, with compassion and even hope.

“Live like you’re in a comedy, not a tragedy, right?” Ayesha reminds her grandfather, when it seems their mosque may be closed down. “This is simply the plot twist at the end of act four,” he agrees.

It’s not a bad way to approach life.

Elizabeth Toohey is an assistant professor of English at Queensborough Community College, City University of New York.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Sudan’s great strength after a massacre

Much of the world has condemned Monday’s massacre in Sudan of more than 100 pro-democracy protesters. Yet on the ground, the reaction among protesters was very different. It may even offer a lesson on how to react to evil acts.

After the Army dispersed thousands of Sudanese outside its headquarters with indiscriminate shooting, the demonstrators simply moved to other parts of the city. Their fight was not with bullets but with the bullying during Sudan’s three decades of repression. They set up new barricades, called for a general strike, and relied on an amazing unity formed during six months of a peaceful sit-in.

The sit-in itself was a microcosm of the kind of society that the protesters seek to create. It was well organized in supplying food and water. It was inclusive of women, workers, and the country’s diverse ethnic groups. People provided lessons in civic education. Organizers took surveys of who should run a transitional civilian government.

The Army’s violence certainly deserves international censure. Yet the world should also take notice of the dignity, democratic ideals, and nonviolent tactics of Sudan’s protesters. Real power does not come out of the barrel of a gun.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

No one is invisible

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Robert R. MacKusick

Moved by a news report on veterans and others without homes who too often feel invisible, today’s contributor considers a spiritual basis for seeing and feeling our and others’ God-given value and worth.

No one is invisible

On the evening news recently there was a report about homeless veterans and others who have no place to live, no job, no dependable food source. One of the men interviewed said, “People think of us as invisible. They don’t know we’re here and they don’t care about our situation.”

When I heard his comments, it made me think more deeply about how I look at those in need. It stirred me to think about ways we can all help – for instance, buying food to give to those in need, making donations to charitable organizations, or giving used clothing to thrift shops.

Yet while it’s so heartening to see people helping in these important ways, behind that stirring was something more. I thought about what the Bible teaches about the importance, even the demand made upon us, of loving one another, seeing our brother’s need, and responding in a way in which we would want someone else to help us.

To me, this isn’t just about items or money we may give others, it’s about how we see them. I’ve found it encouraging to think of people the way God sees them. Christ Jesus once spoke of a shepherd who had 100 sheep (see Matthew 18:10-14). One went astray and left the general flock. The shepherd went out into the mountains to look for that lost sheep; to find it and bring it back to where it belonged with the rest of the flock. The good shepherd loved his sheep and made sure they were all cared for.

This illustrates, as Jesus explained, that it is not our heavenly Father’s will that any “of these little ones should perish.” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, was a devoted student of the Bible. In her primary work, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” she wrote: “The rich in spirit help the poor in one grand brotherhood, all having the same Principle, or Father; and blessed is that man who seeth his brother’s need and supplieth it, seeking his own in another’s good” (p. 518). And the marginal heading next to that statement reads, “Assistance in brotherhood.”

What enables us to see our own, as well as our brothers’ and sisters’, value and worth? Even when one takes earnest and selfless steps to find a sense of value through human ways and means, I’ve found there is a need to go deeper. What Christ Jesus taught about himself and others is a great help. He acknowledged his perfect relation to God, his heavenly Father, so many times and in so many ways. Jesus’ whole life and career was evidence of God’s redeeming, uplifting care.

Jesus’ understanding of individuality and worth as divinely established continues to inspire today. His example demonstrates a divine Principle, a basis for seeing our own God-given value, as well as others’. As we recognize that we are all God’s children – the spiritual expressions of His goodness and completeness, forever loved and cared for by Him – we come to see that none of us can ever truly be lost, ignored, or lacking individuality.

That’s because the real basis for our worth and value is not ego, pride, or an inflated sense of mortal self and competition with others. It is our unbreakable relation to God, divine Love – our “visibility” or value in God’s eyes. God cherishes and values every one of us as the expression of His being, just as the caring shepherd cherishes every single one of the sheep he is tending.

Each of us can learn to humbly accept our – everyone’s – origin as the offspring, or expression, of our divine Father-Mother. This may inspire us to do certain good deeds for others, to express in particular ways the selflessness and love inherent in us all. Above all, it enables us to feel our God-given dignity and to see others’ value and worth, too.

A message of love

Triumph after tragedy

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when Monitor reporters Harry Bruinius and Patrik Jonsson will explore what it means to find healing in the wake of a mass shooting.