- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘We are Ivan Golunov’: Russian media fights back after reporter's arrest

- Why tariff threat is unsettling – even after US-Mexico deaI

- As universities push for names, assault survivors fight for anonymity

- How Baltimore is saving urban forests – and its city

- The 10 best books of June to read while you soak up the sun

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Journalists cover war. Why not peace?

What if peace is breaking out in lots of places – but you just don’t know about it?

That question occupies the thinking of Jamil Simon, one of 10 laureates who will receive the Luxembourg Peace Prize this Friday. Mr. Simon, founder of Spectrum Media in Somerville, Massachusetts, is being honored for his half-century effort to build global awareness of peaceful solutions to conflict.

To Mr. Simon, his “uphill battle to make peace more visible” means talking to journalists, whose work reaches hundreds of thousands. It means shifting a mindset of “if it bleeds, it leads” that often boosts fear. “If the public doesn’t see peace as a viable solution to conflict,” says Mr. Simon, whose work currently focuses on Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Colombia, and Burundi, “people will accept a default move to war and violence.”

Violence certainly roils many countries around the world, and conflict is filled with drama. But so is the peacemaking that happens far from the halls of power, he says. “I want to open people’s eyes that there are stories here of human transformation. I know how hard it is to tell stories about peace because I’m making a film about it. But there are ways into these stories that reveal the distance people travel in their journey trying to reconcile.”

The bottom line is getting people to “look at something differently,” Mr. Simon says. And he’s making headway. Ahead of the first War Stories Peace Stories Symposium in New York last year, which he organized with Peace Direct for journalists, a call went out for peace-building story proposals. It yielded 200 pitches from 60 countries, the quality of which prompted the Pulitzer Center to triple its grants. When the conference convened, Mr. Simon says, “the atmosphere was electric.”

Now to our five stories.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘We are Ivan Golunov’: Russian media fights back after reporter's arrest

After a colleague’s arrest last week, Russian journalists did something very unexpected: They pushed back. It could be a pivotal challenge to Vladimir Putin’s repressive political culture.

The arrest and detention of investigative reporter Ivan Golunov in Moscow over the weekend has created what could be a pivotal moment in the relationship between Russia's Fourth Estate and the government.

Mr. Golunov is the author of some of the most penetrating studies of the nexus between crime and corrupt authorities being published for Russian audiences today. After his arrest Thursday on dubious drug charges, Russia’s independent trade union of journalists called on its members to picket police stations around Russia. At least 100 showed up in Moscow on Friday, and dozens were detained by police. Three leading Russian newspapers came out with identical front pages, along with editorials in his support, on Monday.

“I think this Golunov story is a possible game-changer,” says Vladimir Pozner, an elder statesman of Soviet and Russian journalism. “There is a massive outpouring of solidarity from people who do not normally take political stands. It shows that there is a gradual understanding that if you don’t stand up for your colleagues when they are being repressed, you better keep in mind that you too will be repressed.”

‘We are Ivan Golunov’: Russian media fights back after reporter's arrest

Very few Russians had even heard of Ivan Golunov before his arrest for alleged drug possession Thursday.

But what had begun as a typical Putin-era case of what is sometimes called lawfare – abuse of the police and prosecutorial machinery to brand political opponents as criminals – waged against a journalist has blown up into what could be a pivotal moment in the relationship between Russia's Fourth Estate and the government.

An investigative reporter for the Latvia-based Meduza online news service, Mr. Golunov is the author of some of the most penetrating studies of the nexus between crime and corrupt authorities being published for Russian audiences today. (Many are also available in English.)

For Russian human rights monitors, what happened Thursday is a familiar story. On his way to meet a source, he was detained by police, who claim to have found packets of mephedrone, a designer drug, among his things. A search of his apartment subsequently turned up more narcotics, along with a set of scales, indicating that he was involved in drug dealing. A terse statement from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which oversees the police, lays out the case against him and denies allegations that he was subsequently beaten and mistreated by police.

But what followed was not typical. Russia’s independent trade union of journalists called on its members to picket police stations around Russia; at least 100 showed up in Moscow on Friday, and dozens were detained by police. Many Russian celebrities recorded YouTube messages of support for Mr. Golunov. Three leading Russian newspapers came out with identical front pages, along with editorials in his support, on Monday.

There was an outpouring of social media memes of solidarity; weekend gauges of Russian social media found Mr. Golunov topping Vladimir Putin in mentions as his story went viral. And supporters have organized a public rally in central Moscow for Wednesday, which is Independence Day, an official holiday in Russia – and they have pointedly defied authorities by declining to ask for permission.

“This is the biggest campaign of journalistic solidarity in Russia for a long time,” says Ivan Kolpakov, Meduza’s editor-in-chief, speaking from his office in Riga, Latvia. “I never expected this kind of support. I am pleased, surprised, and hopeful that it will help to free Ivan [Golunov]. Of course, that is our No. 1 priority: to secure his safety, his freedom. But if it is also helping to change Russia’s political culture and space for journalistic activity, that is wonderful too.”

Meduza, which largely covers Russian affairs, aims at a wider Russian-speaking audience, including in the former Soviet Baltic states, and also publishes some of its output in English.

“We are based in Latvia as a matter of safety,” says Mr. Kolpakov. “It gives us more room for independence and creates another perspective on Russia.”

‘A possible game-changer’

Nothing like this has happened in Russia for at least 15 years.

It may represent a tipping-point for Russia’s beleaguered press corps. They have long been stereotyped as conformist, self-censoring, and official-line-toeing journalists who have learned to live in a virtual straitjacket ever since Vladimir Putin brought the freewheeling 1990s media to heel in a wave of state takeovers after coming to power nearly 20 years ago.

The image of Russia’s Putin-era media as a Kremlin-dominated monolith has never been quite true. But the state has permitted its law enforcement agencies as well as freelance political forces to intimidate and crack down on journalists viewed as working outside the acceptable spectrum of news production.

Russian journalists are pushing back, and trying to lay down some markers to authorities because they can, says Stepan Goncharov, an expert with the Levada Center, Russia’s only independent public opinion agency.

“This shows that journalists are the most consolidated social group,” Mr. Goncharov says. “It demonstrates that they are able to communicate, come to an understanding of common interests, and express themselves publicly. These three newspapers – Kommersant, RBK, and Vedomosti – are not in opposition [to the government]. They are aroused not so much by the arrest of Golunov, but the way it was done. The accusations are unrealistic, they treat public opinion with disdain, and that is the catalyst for the discontent we are seeing.”

The Golunov case has raised hopes – as well as doubts – that Russian political culture might be changing and, along with it, the prospects for the country’s Fourth Estate to expand its professional footprint.

One sign that the landscape might be changing in the face of widespread public protest: On Saturday a Moscow court defied a prosecutor’s demands and allowed Mr. Golunov to be moved to house arrest pending trial, where he will be in full contact with his friends and supporters. Russian prosecutors usually get their wish to have prisoners held in pre-trial detention centers, where they are under full police control.

One feature of the present moment is that a wide range of people have come forward to defend Mr. Golunov, and not just the usual liberal activists and opposition media voices. Vladimir Pozner has been a fixture of Soviet and Russian media for many decades and, as host of the state-run Channel One’s top-rated interview show, “Pozner,” he presumably has a lot to lose by speaking out.

“I think this Golunov story is a possible game-changer,” Mr. Pozner says. “The Soviet Union and Russia have not tended to be healthy environments for public protest. But we are seeing a very important change. There is a massive outpouring of solidarity from people who do not normally take political stands. It shows that there is a gradual understanding that if you don’t stand up for your colleagues when they are being repressed, you better keep in mind that you too will be repressed.”

The arrest of Mr. Golunov, he says, “is an attempt to cow not only him, but everyone involved in investigative journalism. I am optimistic that it will fail, and we will all find ourselves in a better place as a result.”

‘We are not one army’

Some do question the leap to defend Mr. Golunov. “There are lots of journalists who use and even distribute drugs, this is not a secret,” says Nikolay Starikov, leader of the conservative social movement Patriots of Great Fatherland. “So how does it happen that everyone just assumes Golunov’s innocence, without even waiting for the results of even the preliminary investigation? That’s just pure bias.”

And some journalists, while struck by the outpouring of support, are dubious that it marks a shift. “Yes, it’s remarkable that a lot of journalists are not sitting silent about this Golunov case,” says Sergei Strokan, foreign affairs columnist for the Moscow business daily Kommersant, one of the three mainstream papers that supported Mr. Golunov on their front pages Monday. “But there are journalists, and there are journalist card-holders. Lots of places filled with journalists are conspicuously not speaking up.

“If you go to Sputnik, or [the government newspaper] Rossiskaya Gazeta, you will find lots of journalists who accept the state narrative that Golunov is just a troublemaker, and Meduza is an agent of foreign interests. So, the fact that these three papers are supporting Golunov looks more like an act of desperation than some kind of breakthrough,” Mr. Strokan continues. “This is not a protest of the journalistic community. We are not one army with the people at RIA or Rossiskaya Gazeta, and our authorities are very good at playing one group against another.”

Ironically, Kommersant itself was the scene of a bitter struggle last month when its entire domestic newsroom resigned in protest over the firing of two journalists by the paper’s Kremlin-friendly oligarch owner – a scandal that was covered in full by Meduza.

Mr. Strokan, who lost his job with the independent media group Media Most in 2001 when the then-new Putin administration took it over, says he is gloomy about the prospects of anything changing. “Look at the calendar, it’s 2019,” he says. “There were huge rallies in support of media freedom two decades ago, and we were all eventually ground down. I’m not being pessimistic here, just realistic.”

Mr. Pozner says it’s different this time, because two decades ago people had tasted the political and press freedoms of the 1990s, and were less fearful of the consequences of speaking out.

“It’s been made abundantly clear that to fight the powers that be is a dangerous path, even a hopeless one,” he says. “Nevertheless, we are seeing this upsurge of public spirit and journalistic solidarity today. That’s amazing.”

Editors note: This story has been updated to correct the Russian national holiday on Wednesday.

Why tariff threat is unsettling – even after US-Mexico deaI

Should tariffs be deployed to achieve political or diplomatic ends? Our reporters examine the host of questions that President Trump's threat against Mexico has raised.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Whitney Eulich Correspondent

The Mexico tariff threat has been dodged, for now. That’s the bottom line of the bilateral agreement between the U.S. and Mexican governments announced by President Trump last Friday.

But if the short-term outlook is relief, the longer-term outlook is more mixed. Yes, U.S. manufacturers, farmers, and consumers won’t have to suddenly adjust to Mr. Trump’s threatened tariffs of 5% to 25% on goods imported from Mexico.

But the president says he maintains the right to impose such tariffs if he thinks Mexico isn’t doing enough to slow the flow of Central American asylum-seekers across the southern U.S. border. And in a larger sense, the new U.S. willingness to weaponize tariffs may have frayed trust between America and a wide range of allies and trading partners. That could be a big problem in other diplomatic and economic situations in months and years ahead. “What the president is weakening is much bigger than most people understand immediately,” says Earl Anthony Wayne, a former U.S. ambassador to Mexico. “It is really threatening the very basic set of principles on which American competitiveness is built. It is built on doing things with our neighbors.”

Why tariff threat is unsettling – even after US-Mexico deaI

Businesses across the United States and Mexico breathed a sigh of relief after President Donald Trump announced a bilateral agreement Friday over border security that would avert his threatened tariff on Mexican goods.

No industry had been holding its breath more than the auto industry, for which a 5% to 25% tariff could have been disastrous given the huge cross-border flows of parts and cars.

“Our industry is [already] facing 25% tariffs on imported steel, 10% tariffs on imported aluminum, and a 25% tariff on the vast majority of inputs into our manufacturing process that come from China,” says Ann Wilson, the Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association senior vice president of government affairs. “Additional [tariffs] would mean that suppliers and customers will have to look at the most cost-friendly place to manufacture the components in a vehicle.”

Yet even as an immediate risk has been dodged for factories and farms – at a time when both nations show signs of economic weakening – the wider message is more mixed. Mr. Trump’s tariff threat remains alive if Mexico’s border actions don’t prove strong enough, in his view. Given the president’s bluster-and-bash approach to dealmaking, it’s quite possible that the claimed progress with Mexico could unravel. And even if it doesn’t, the U.S. willingness to weaponize tariffs against a close trading partner may have frayed diplomatic trust.

“What the president is weakening is much bigger than most people understand immediately,” says Earl Anthony Wayne, a former U.S. ambassador to Mexico. “It is really threatening the very basic set of principles on which American competitiveness is built. It is built on doing things with our neighbors.”

The threat of tariffs started late last month as migrant apprehensions spiked at the southern border. Mr. Trump justified his actions by calling the situation at the southern border a “national emergency,” a designation that allowed him additional leeway in his response.

The ploy appears to have worked – although the extent to which the deal had been agreed upon prior to the Trump threat flared into its own separate debate over the weekend. Mexico has agreed to roll out 6,000 National Guard troops, mostly on its southern border, to crack down on migrants traveling north towards the U.S., and to increase the reach of a program that requires asylum-seekers in the U.S. to wait in Mexico.

Mexico’s enhanced border security rollout could score the president points with his immigration-conscious base. Many Trump supporters praised the announcement. And GOP Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin said the president used the tariff threat “brilliantly” as leverage for border security.

But any political win is tenuous. Mexico did not agree to become a “safe third country,” which would allow the U.S. to reject asylum-seekers that passed through Mexico but did not first apply for asylum there. Mr. Trump also tweeted Monday that the deal had elements that would require approval by Mexico’s legislature, and that “if for any reason the approval is not forthcoming, Tariffs will be reinstated!”

And the concessions offer no solution to the real problems – like gang violence, government corruption, climate change, and overall lack of education and employment opportunities – driving immigrants from Guatemala and Honduras northward through Mexico. Trust between the two countries is breaking down right as they’re seeking ratification of a new U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement on trade.

“It’s a strange thing to, with one hand, say we’re entering into a new zero-tariff trade agreement and, with the other hand, say I’m going to impose a five percent tariff on you to coerce you into doing something that I want you to do, separate from trade,” says Joel Trachtman, an international law professor at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. “It seems really strange to treat Mexico, our ally and longtime friend, that way.”

Economies joined by trade

Experts worry the two nations are so economically intertwined that tariffs would cause serious harm. Mexico’s gross domestic product already contracted in this year’s first quarter. And by one forecast, a 5% tariff on Mexican goods would cost the U.S. economy $41 billion and more than 400,000 jobs. The specter of these losses made Mr. Trump’s proposals widely unpopular with U.S. business leaders and Republican lawmakers, and their resulting pushback likely contributed to the signing of the deal.

For Glenn Altschuler, a professor of American Studies at Cornell University, the tariffs were a perversion of trade policy.

“The trade war with China is based on some premises by the Trump administration that should be of concern to Americans and are relevant to the issue of trade,” he says. “The proposed tariffs on Mexico actually have nothing to do with trade. They’re about an immigration issue and are being used as a political tool outside the realm of trade.”

Few in Mexico see Friday’s agreement as the end of U.S. demands around border security. Both countries are expected to check in at the end of July to see how measures agreed to last week are playing out. However, uncertainty around what Mr. Trump and his immigration-hawk advisors will deem a success already has some bracing for another round of economic threats from the U.S.

“There are plenty of scenarios, unfortunately, where we will arrive once again at a situation like last week,” says José María Ramos, investigator in the public administration department of the College of the Northern Border (COLEF) in Tijuana. “Mostly because it’s completely unclear what quantity of migrants Mexico has to stop in order to satisfy the U.S.”

Mexico’s new administration, inaugurated in December, took office promising not to criminalize migration, and created a number of initiatives, like humanitarian and work visas, that observers say incentivized migration. But President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration has deported nearly 70 percent more migrants in April and May than the outgoing administration did during the same timeframe in 2018.

Those working on migration in the region are concerned about how Friday’s agreement will play out. They point out that as of June 5, more than 10,000 Central Americans have already been returned to Mexico from the U.S. via the Migrant Protection Protocols program, according to Mexico’s National Institute of Migration.

“What they seem to be saying is that they’re going to return everyone,” says Gretchen Kuhner, director of the NGO Institute for Women in Migration in Mexico City.

That would have hefty economic implications for Mexico, which has promised to provide education and healthcare for this population.

“What this [agreement] is going to do is that once people get to the border they’re not going to turn themselves in anymore. They’ll rely more on smugglers so they can enter the U.S. undetected, ” says Ms. Kuhner.

She says what’s really going to bring down the number of migrants and asylum seekers at the U.S. border are much longer-term steps, like economic development efforts in Central America.

“The political timing doesn’t allow for long-term solutions,” she says.

‘Space for cooperation’

Moving ahead, Mexico is likely to continue working to appease the U.S. Many citizens say they’re content with Mr. López Obrador’s approach to Trump’s threats last week. Mr. López Obrador responded with calls for continued friendship between the U.S. and Mexico, and his approval ratings went up by four points between May 27, the day of Mr. Trump’s announcement of potential tariffs, and the following Tuesday.

An incentive for Mexico to discuss solutions to migration, even if under threat of tariffs, is that “it’s a recognition that migration is a problem with humanitarian, security, and development implications for both the U.S. and Mexico. It requires U.S. cooperation,” which Mexico gets, in a way, through negotiations like the ones that took place in the lead-up to Friday’s announcement, says Dr. Ramos.

“We are living in a complex and interesting time on the U.S.-Mexico border, but there is space for cooperation,” he says.

A key question is whether that will happen with a U.S. president who leans on immigration as an issue that can energize his base heading toward another election.

For one thing, experts worry that indiscriminately invoking national emergencies for political gain sets a dangerous precedent.

“President Trump is the first one to use that discretion to declare an emergency or a national security threat so promiscuously,” says Mr. Trachtman.

Mr. Wayne, the former ambassador, says the diplomatic and economic instability is not worth the perceived political gain.

“What’s the better kind of a relationship: tackling problems together, or do you want a relationship where there’s a deep resentment and only a grudging cooperation where it has to be done and then looking strongly for other options? It’s just not a good way to build a long term partnership.”

Staff writer Mark Trumbull contributed to this story from Washington.

As universities push for names, assault survivors fight for anonymity

Can sexual assault victims seek both justice and privacy? This story looks at two universities' requests that go to the heart of balancing compassion and fairness in court.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When students come forward to report sexual assault, they expect some level of privacy. But two colleges have recently taken the position that privacy shouldn’t always extend to students who are suing them.

Both schools are accused of violating an anti-discrimination law known as Title IX by not responding adequately to sexual harassment and violence. The student plaintiffs say they fear irreparable harm if their names are exposed, while the schools say that hiding the names hampers their defense.

The cases, involving Dartmouth College and Florida A&M University, raise the question of whether people can seek both justice and privacy under Title IX – or whether they may in some instances have to choose. The debate hinges on how to balance fairness and compassion in the legal system and in educational settings nationwide.

Peter Lake, a professor at Stetson University College of Law, expects such battles to continue. Preserving some level of privacy or confidentiality “has been a persistent question that’s been coming up in Title IX work,” he says, adding, “the fear being that if you don’t, it may chill people from going forward.”

As universities push for names, assault survivors fight for anonymity

“Jane Doe 2.” “Jane Doe 3.” “S.B.” This is how three women are known in court documents. All three say they suffered sexual violence and that their colleges knew enough to better protect them. They feel betrayed.

The women want to maintain privacy while asking for monetary damages and better accountability for how the campuses address sexual misconduct and assault.

The schools facing these federal Title IX lawsuits – Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, and Florida A&M University – deny that they responded inadequately, and have asked the courts to not allow the women to use pseudonyms. They know the women’s identities but say that having to keep them confidential would hamper their defense.

Such cases raise the question of whether people can seek both justice and privacy under Title IX – or whether they may in some instances have to choose. The debate hinges on how to balance fairness and compassion in the legal system and in educational settings nationwide.

The colleges’ legal tactics are gaining national attention because “it certainly has been more common to let cases proceed on pseudonyms,” says Peter Lake, a professor at Stetson University College of Law in Gulfport, Florida.

But he also expects such battles to continue. “This has been a persistent question that’s been coming up in Title IX work – preserving some level of privacy or confidentiality ... the fear being that if you don’t, it may chill people from going forward,” he says.

Among more than 500 people who have signed a petition calling for Dartmouth to withdraw its opposition to the women’s privacy are Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York and Rep. Annie Kuster of New Hampshire, both Dartmouth alumnae, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

Empowering survivors

Even in the #MeToo era, when many have opted to go public to raise awareness, doing so can come at immense personal costs, and survivor advocates say it should always be their choice.

“Survivors who find the courage to report what they endured must be empowered, at all times, to control their privacy in the interest of their mental health,” wrote S.B.’s lawyers, Michael Dolce and Takisha Richardson of Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll, in a May 29 letter about the public university to more than 40 Florida legislators.

Judge Mark Walker in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida has denied multiple motions by Florida A&M University (FAMU) to reveal S.B. – who alleges rapes and retaliation for reporting. “There is absolutely no legitimate public interest in outing a rape victim in a Title IX case,” he wrote in a 2018 decision.

FAMU recently asked the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to consider the issue.

The university has bolstered staffing and policies to support students reporting sexual misconduct and is “merely asking for a fair and open trial,” FAMU says in an emailed statement. “The plaintiff is an adult demanding monetary damages under Title IX and the University has asked that her legal name be provided to jurors at trial.”

To Mr. Dolce, that statement suggests a worrisome “shift away from due respect for those who report these crimes,” he says in a phone interview.

While not commenting on the specifics of either case, Professor Lake notes that some universities may think they don’t have a level playing field when stories about a lawsuit with an unnamed plaintiff are swirling in the media. “If you are trying to combat a narrative about your institution, you can only fight with a ghost,” he says.

If the 11th Circuit agrees to hear the matter, it could have “huge implications” for Title IX lawsuits, says Teri Mastando, an attorney in Alabama.

A decision would be “binding on Georgia, Florida, and Alabama in the federal court system,” she says. If the court were to rule generally against filing anonymously, the decision might also be considered by other circuits.

Ms. Mastando once represented a girl who was sexually assaulted in middle school. Her parent sued on her behalf, using only her initials. By the time of appeal, she was 19 and wanted to become the proper plaintiff, and the school defendants moved for the court to require her to reveal her identity.

Just because her client was older didn’t mean she should have to give up her privacy, Ms. Mastando argued before a three-judge panel on the 11the Circuit. The judges agreed and the plaintiff won the appeal.

If the name becomes public online, she adds, the sexual assault “becomes fodder for the world. People shouldn’t be able to search for this information.”

Why Dartmouth objects

In November 2018, six named women and one Jane Doe filed a $70 million class-action lawsuit against the Dartmouth Trustees on behalf of female undergraduate and graduate students in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, alleging that the college did not intervene sufficiently after reports of sexual harassment, assault, and retaliation by three male faculty members.

One plaintiff says she was raped several weeks after reports were made in 2017. The other two Jane Does joined the suit last month.

Dartmouth says in a press statement that it promptly investigated reports in April 2017 and sought to fire the men for misconduct, but two resigned and one retired before that process was complete.

“[W]e want to encourage reporting of sexual misconduct so that we can address it,” Dartmouth says in a separate statement emailed to the Monitor. “However, Dartmouth believes that the law is clear that individuals wishing to be class representatives in a class action law suit, which their case is, cannot be anonymous.”

Lawyers for Jane Does 2 and 3 question in their court response why the school objected to their pseudonyms but not to the first Jane Doe’s. They also cite cases in which plaintiffs have been allowed to use pseudonyms in class-action lawsuits.

Dartmouth may opt to challenge Jane Doe 1’s pseudonym at a future time, writes Justin Anderson, vice president for communications, in an email.

“It is extraordinarily unusual for a class action [lawsuit] to proceed with an anonymous class representative,” writes Joshua Richards, a partner at Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr in Philadelphia, in an email. He notes he is speaking about cases generally, not just in the Title IX context.

Jane Doe 3 asserts in a court document that the trauma from sexual assault by her professor continues to affect her, but that she has built a professional life in a new location. In addition to hampering her recovery, she says, “I fear that public identification would wrongly and irreparably tarnish my scientific career.”

Dartmouth’s objection “says to us, ‘be fully exposed, risk everything, or be silent,’” Jane Doe 3 notes.

Another of Dartmouth’s objections is that it would be difficult to investigate potential witnesses without revealing plaintiffs’ names. The plaintiffs argue that judges can issue protective orders to set up fair terms for investigating without revealing the name publicly.

These arguments are now on hold while the parties try mediation. If that fails, the court will pick up where it left off.

‘The tide is starting to turn’

Diana Whitney decided not to wait to see if mediation falls through. As a member of the Dartmouth Community Against Gender Harassment and Sexual Violence, she helped lead a coalition of student, faculty, and alumni groups in urging Dartmouth to withdraw its objections to the pseudonyms.

Dartmouth is “paying lip service to their ‘support’ of survivors, but this is legal massaging to cover up that what they are doing is institutional bullying,” Ms. Whitney says.

Still, big institutions can mean many things to many people, often at the same time. Ms. Whitney received a strong liberal arts education at Dartmouth, graduating in 1995. But it’s also the place where she was sexually assaulted by another student her freshman year, she says.

She sought counseling but did not report it. She found “kindred spirits” who helped her “push back against the dominant culture” on a campus where women were first admitted just two decades before she arrived.

The three male faculty are now banned from campus, but Ms. Whitney applauds the plaintiffs for their “call to action for the community to go beyond individual perpetrators” and “look at the institutional accountability.”

Dozens of comments have come in response to the petition. Some urge Dartmouth to “be better,” “keep your integrity.” Others are more sharp: “Shame on you for a campus culture of silence.”

The outpouring has given Ms. Whitney glimmers of hope that much of the public wants to help eliminate sexual violence.

“I believe the tide is starting to turn,” she says.

A deeper look

How Baltimore is saving urban forests – and its city

The words “city” and “forest” don’t usually go together. But trees are enormously important to livable and safe urban environments. Just ask Eric Dihle, arborist for the city of Baltimore.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

National press about Baltimore tends to focus on the negative – the violent crime rate, ingrained poverty, and police force and school problems. What the headlines don’t often share is that the city is a model for green management, one that has gained attention as a successful urban forest experiment.

With concern growing about climate change and rapid worldwide urbanization, city forests have emerged as one solution to a host of social and environmental challenges. In 2015, the World Economic Forum named increasing green canopy coverage as one of its top 10 urban initiatives.

Much of the understanding of how trees affect everything from climate to criminal justice stems from a technological breakthrough pioneered in Baltimore that lets scientists synchronize forest maps with other data including health records, census figures, crime statistics, and property values. The insights reveal some striking trends: Crime declined when tree canopy coverage went up. Temperatures spiked in areas with fewer trees, and with more trees, housing values increased.

“They impact work productivity, wildlife habitats, air pollution removal, carbon sequestration, energy use,” says David Nowak, senior scientist with the U.S. Forest Service. “Nature is giving us this amazing resource. ... We should ... use nature to make our lives better.”

How Baltimore is saving urban forests – and its city

From his headquarters office, Erik Dihle drives into what has become one of the most monitored forests in the United States.

He begins to point out the trees: There is a tulip poplar, as big as the ones George Washington planted at Mount Vernon. There are the blossoming cherries, with a cotton-candy display that rivals their famous compatriots down the road at the Tidal Basin in Washington, D.C. And there is a white oak, Maryland’s state tree, with its branches gnarling horizontally for yards.

“This is a good-size one,” he says, getting out of his truck to pace the area of shade created by the tree’s canopy. “I’d be surprised if it was less than 150 years old.”

A few blocks away, someone lays on a horn, and traffic begins to move along one of this city’s main arteries. Construction vehicles beep as they repair an old municipal reservoir. And Mr. Dihle jumps back into his truck, ready to show more trees.

Mr. Dihle’s forest is in the city. He is the arborist and the head of forestry for the city of Baltimore, which means he monitors all the trees here – those growing in shady parks, in metal grates along busy streets, in backyards, and in relatively untouched forest patches dotting the municipality. Together, these trees make up what is called the city’s “urban forest,” a type of ecosystem that is gaining attention at both the national and international levels among everyone from environmentalists to politicians, social justice advocates to corporations.

With concern growing about climate change and rapid worldwide urbanization, city forests have emerged as one widely touted solution to a host of social and environmental challenges. Municipalities from Barcelona, Spain; to Melbourne, Australia; to Chicago have put urban canopy coverage at the center of their long-term strategic plans. Community groups focusing on planting, maintaining, and saving trees have blossomed across the U.S. In 2015, the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on the Future of Cities named increasing green canopy coverage as one of its top 10 urban initiatives.

Yet at the same time, the U.S. Forest Service, which in the past decade has also upped its focus on urban forests, has found that American cities are losing trees – and quickly.

A Forest Service report published last year found that across the U.S., populated areas lost about 175,000 acres of trees per year between 2009 and 2014, or approximately 36 million trees per year. Forty-five states had a net decline in tree cover in these areas, with 23 of those states experiencing significant decreases. Meanwhile, urban regions showed a particular decline, along with an increase in what the researchers call “impervious surfaces” – in other words, concrete.

But not, it turns out, in Baltimore.

Here, the net tree canopy coverage has increased. Not by a lot, Mr. Dihle is quick to point out – only from 27% of the city’s land coverage to 28% – and not because Baltimore hasn’t lost trees. It has. But overall the tree canopy here has grown, which means that Mr. Dihle has found himself presiding over one of the more successful efforts in the U.S. to preserve and improve the urban forest.

It’s become an improbable green model for cities around the world.

The intersection of trees and urban living

Trees have been in cities, of course, for centuries. Documents from early New England settlements include rules and regulations about how residents should make use of trees growing on town commons. Many municipalities appointed tree wardens to make sure everyone followed the law. Even the modern concept of urban forestry has been around since the 1960s, when officials in the Johnson administration looked toward nature, and trees in particular, to help revitalize urban landscapes that they perceived to be crumbling.

But in recent years, scientists say, demographic trends have shifted attention toward the urban forest in a new way.

Across the world, there is a rapid and increasing movement of people from rural areas to cities. In 2009, the United Nations estimated that 3 million people worldwide moved to a city every week. By 2015 more than half of the world’s population lived in urban areas, according to the U.N., with the number of city dwellers expected to grow from 3.9 billion to 6.7 billion by 2050.

The same is true in the U.S. More than 80% of Americans live in urban areas, even though cities account for only 3.6% of the country’s landmass.

At the same time, new technology has let researchers better understand the urban ecosystem – not just how trees thrive or fail in a city, but how they intersect with humans.

“They impact work productivity, wildlife habitats, air pollution removal, carbon sequestration, energy use,” says David Nowak, senior scientist with the U.S. Forest Service who authored the recent national report on tree canopy loss. “We might as well work with the forests. Nature is giving us this amazing resource. ... We should be smart about this whole process and use nature to make our lives better.”

Much of the understanding of how, exactly, trees affect everything from climate to criminal justice stems from a technological breakthrough pioneered in Baltimore.

For decades, scientists recorded their data on paper, filling notebooks and filing cabinets. With the advent of computers, foresters were able to tabulate and analyze the information in a new way. By the 1990s, satellite imagery allowed governmental agencies such as NASA to produce visible images of Earth and to show on various scales where trees existed.

But there was a limit to those pictures, explains Morgan Grove, a scientist with the U.S. Forest Service who has worked in Baltimore since 1999. Because the data were recorded in pixels, not physical parcels, it was difficult to identify, say, the owner of a particular tree, or to compare what was happening from one city block to another.

In 2006, though, the Forest Service, working with researchers from the University of Vermont’s spatial analysis lab, put together a new type of land cover map in Baltimore using a combination of aerial imagery, light-reflecting technology, and high-resolution landowner data. This novel approach not only allowed a closer look at trees, it also let scientists synchronize forest maps with other information that was also newly computerized and manipulable – everything from health records to census figures, crime statistics to property values.

“Now we can talk about trees and how they relate to other systems,” Mr. Grove says. “Our ability to combine data systems in novel ways – we couldn’t do that 30 years ago.”

The insights revealed some striking trends. Crime declined when tree canopy coverage went up. Temperatures spiked in areas with fewer trees, an effect known as a “heat island,” and with more trees, housing values increased.

With parcel-by-parcel data, city officials could see precisely where trees had been removed and where canopy had increased. They could zoom in on a particular block, or even a house, and see which trees existed there as well as the age, health, and size of the stock. They could also determine how much carbon sequestration, cooling effect, and crime mitigation any particular tree gave a city. And from there, researchers could put a dollar figure on a tree, an approach that fit a larger trend of environmentalists trying to show the value of natural resources in monetary terms.

Cities around the country and world began implementing the technology and started to notice additional patterns. In London, for instance, officials found that in areas with greater tree canopy coverage residents took markedly fewer prescription antidepressants. One neighborhood in Chicago found that a tree initiative saved each resident nearly $100 in heating and cooling costs. In New York City, advocates armed with statistics about the financial impact of trees launched a hugely ambitious – and ultimately successful – effort to plant 1 million trees in the city within 10 years. Today, scientists in New York are using tree maps to show areas most in need: places where trees could help cool neighborhoods heavily populated with elderly, minority, and impoverished residents.

Around the world, as scientists mapped more and more trees, they understood better how urban forests affect everything from land use to natural disaster mitigation.

“Baltimore was the first place where we did the whole city,” Mr. Grove says. “Now we have done the entire Chesapeake Bay watershed. We’ve done the whole Northeastern U.S. It would cost some money, but it’s possible to do the entire U.S. Which [would be] transformative.”

Baltimore, an improbable green model

Baltimore is perhaps an unexpected model for green management. The city has not been building a reputation for governmental effectiveness recently: During the first week of May, Mayor Catherine Pugh resigned amid corruption allegations, while a week earlier a former city police officer was sentenced to nine years in prison for helping run a drug gang with other officers. National press about Baltimore, when there is any, tends to focus on the negative – the violent crime rate, the ingrained poverty, the struggles of its police force and school system.

But what the headlines don’t often share is Baltimore’s long-standing environmental focus. Sitting on the Chesapeake Bay, the city is headquarters for numerous researchers and environmental organizations studying and protecting the country’s largest estuary. It was this work that led to the city’s leading role in urban ecology.

In the late 1990s, scientists were trying to figure out how to reduce the amount of nitrogen in the bay. For years, agricultural runoff and urban pollution had been despoiling the ecosystem. Because of other research done in more rural areas, scientists believed that one solution was to plant trees alongside streams and inlets. But when they started testing, explains Mr. Grove, they discovered that, for a number of biological reasons, a better way to reduce nitrogen in the Chesapeake Bay was to plant trees throughout Baltimore.

Soon, the National Science Foundation took interest in the work and funded what would end up being a 20-year ecological study in the city. It was one of the first big investments in urban ecology, Mr. Grove says, and the roots of the tree map initiative.

Now Mr. Dihle, the city arborist, uses that tree map regularly. Along with the age, location, and species of trees, his department can harness the technology to note which of the city’s 2.6 million trees need pruning, whether any are sick, and which neighborhoods are due for tree maintenance.

This way, he says, “we make sure those trees are not falling down in a storm, not becoming a nuisance to the neighborhood. ... We don’t wait for it to be a complaint.”

Not only does this keep residents happy but it also maintains canopy coverage. Large, older trees have far more leaf span, and thus ecological impact, than newly planted trees.

“We all love the new tree plantings,” Mr. Dihle says. “We like to get our picture taken and there we are with the shovels and the schoolchildren all around. But when I got here the concern was the mortality rate: how many [of the new trees] are still alive four or five years later.”

Urban forest crusader

Mr. Dihle arrived in the city eight years ago. He had just retired from the U.S. Department of the Army, where he was a civilian in charge of managing the 12,000-tree Arlington National Cemetery. Some people were surprised when they heard that Mr. Dihle was planning to spend his retirement working for Baltimore, and in a position that, as Mr. Grove says, requires him to be able not only to cut down a tree and cut up a tree, but also to “be one of the most patient people in the world. And deal with disasters.”

But with the laid-back vibe of his California upbringing, Mr. Dihle responds to questions about this with a shrug and a smile.

“I think I can make a difference,” he says. “And between the tree canopy and the status of urban forestry here, we are making a difference.”

He moved to a neighborhood close enough to bike to forestry headquarters, the entrance of which is now graced by a sculpture of Dr. Seuss’ Lorax wearing hiking sandals. Mr. Dihle says he found a city far different from what the headlines and reputation suggested. Baltimore had not only a deep scientific base, he says, but also great neighborhoods, a revitalizing downtown, and the sort of community activism that makes environmental innovation possible.

“We’re at the forefront of a lot of green infrastructure,” he says. “We have a lot to champion.”

Across from his office desk is a stuffed raven – a reference to either hometown poet Edgar Allan Poe or the professional football team, depending on one’s inclination – and a rubber rat, the tongue-in-cheek city mascot. Nearby are bumper stickers and posters for many of the city’s environmental nonprofits. One of Mr. Dihle’s jobs is to coordinate these different organizations. Together they work under the “TreeBaltimore” umbrella and use the city’s tree map data to coordinate tree plantings and maintenance, neighborhood cleanups, and various other initiatives.

There is Blue Water Baltimore, which works to restore the quality of the city’s various waterways. The Baltimore Orchard Project helps plant fruit trees in community gardens around the city. And Baltimore Green Space both works as a community land trust and helps preserve “forest patches” – usually small, and often overlooked, swaths of woodland that dot cities.

Appreciation for a precious urban resource

Springfield Woods is not on Google maps. But walk to the end of Springfield Avenue, or across the street from the low slung, red brick Maplewood Apartment complex on St. Georges Avenue, and it is there: a cool bit of forest in the historically African American neighborhood of Wilson Park on the northwest side of Baltimore.

Butch Berry has spent most of his life going into Springfield Woods. When he was a kid in the 1960s, he remembers playing there, often by the stream that still babbles through the trees. When he came back to the family home in the early 2010s, after working as a cartoonist in Los Angeles, he was drawn to it again.

But by then the woods were different. People dumped trash at the edge of the 3.5 acre parcel. A handful of homeless people had made a campsite in the middle. Poison ivy had snarled the underbrush. Mr. Berry asked around about whether anyone in the neighborhood association was doing anything to keep up the woods. Eventually, he started just picking up trash himself.

“I figured, what are they going to do – arrest me for picking up litter?” he says with a laugh.

Later, he reached out to Baltimore Green Space, to see if the group might help him take care of Springfield Woods. He had heard of the organization because it had recently gotten involved in trying to save another forest patch, Wilson Woods, a few blocks away.

As Katie Lautar, the group’s executive director, describes it, area residents had contacted Baltimore Green Space because they heard that a landowner planned to mow down a vacant acre of old hardwood trees that residents had long used. Until then, Baltimore Green Space had mostly focused on community gardening projects.

But the idea of a city forest was intriguing. It was a situation, Ms. Lautar says, where people simply didn’t see a natural resource in front of them.

“Sometimes folks have, in the wider environmental world, a block about thinking of nature in urban spaces,” she says. “I say that as someone who grew up in Baltimore. I got my master’s in environmental education and came back and I had never noticed these spaces.”

After a number of meetings with residents, who asked to know about the mini forests, she reached out to scientists who could help study the ecological impacts of forest patches and explore how people use them. The group discovered that not only did the forest patches provide important habitats for native species and significant cooling effects for surrounding homes, but they often played an important role in neighborhoods.

“There’s a mythology that people in urban environments don’t like nature,” Ms. Lautar says. The truth is that people use and love the woods. Their research found that the vast majority of some 80 forest patches in the city showed signs of human stewardship – trails, benches, or places where people had weeded. Or there was a person, like Mr. Berry, who had started picking up trash.

Ms. Lautar decided to use Baltimore Green Space’s community activism model to protect these mini forests. Today, the group supports neighborhood “forest stewards” who take the lead in caring for woods.

On one recent morning, for instance, Charles Brown was working on the edge of the remaining half acre of Wilson Woods. Mr. Brown, a retired cab driver, comes by every few days to work on the trail, pull out invasive vines, or plant new seedlings.

“I used to drive by this every day and didn’t notice it,” he says. Now, it’s one of the places in his neighborhood that gives him joy. “It’s peaceful. You get a sense of accomplishment.” He pauses and gives a wry smile known to gardeners everywhere. “If you ever finish anything.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Berry’s Springfield Woods has become a showcase for urban forest patches. Since Baltimore Green Space began its partnership with him, volunteers from around the neighborhood and beyond have come into the woods to pull out the poison ivy, build trails, and haul out trash.

“We found everything in here from a vacuum cleaner to an old gun,” Mr. Berry says.

Now there are benches and clearings and a sign at the edge of the forest welcoming visitors. Mr. Berry and Baltimore Green Space have hosted events in the woods, including an edible hike, in which participants cook food harvested from the forest. When the group recently organized a “haunted woods” evening, more than 90 people attended. There is still trash, but much less of it, and Mr. Berry has watched as the same neighbors who once used the woods as a dump now yell at people throwing litter from their cars.

“Between the tree canopy and the urban forestry here we are making a difference,” says Mr. Dihle. “It all ties together. ... It ties into social equity, into climate adaption, everything.”

Books

The 10 best books of June to read while you soak up the sun

If you are looking for a few good books to curl up with this June, our reviewers have curated a list of 10 good reads, from “a gorgeous, deeply affecting story” about family and forgiveness to a kaleidoscopic journey through the Ottoman Empire.

-

By Staff

The 10 best books of June to read while you soak up the sun

This June, relax and soak up the rays while you enjoy the top 10 best books of the month. The list is full of exciting, feel-good stories.

1 Strangers and Cousins

by Leah Hager Cohen

What could be more romantic than getting married in your family’s ancestral home? Lots of things in Leah Hager Cohen’s timely, timeless comedy. For one, the barn is about to collapse and the house isn’t in much better shape. For two, the parents plan to sell up right after the wedding. For three, their daughter is planning less a heartfelt ceremony and more “an ersatz comedy on the institution of marriage.” Then someone steals the wedding ring.

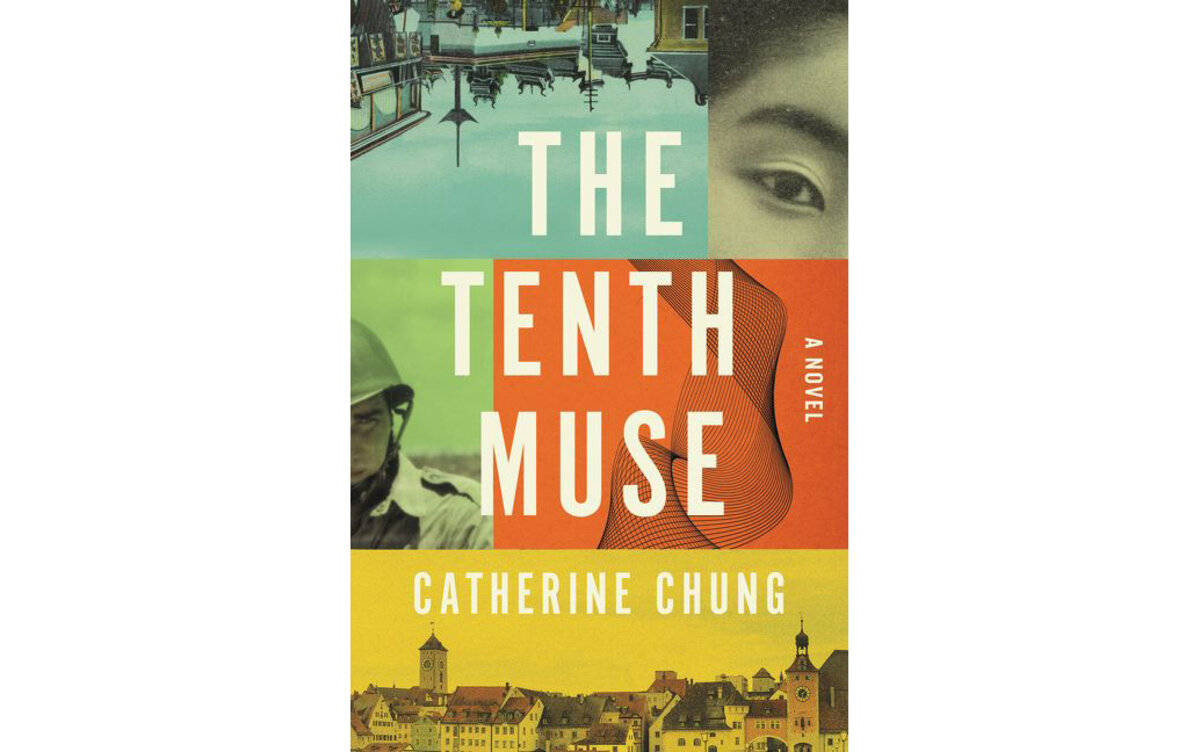

2 The Tenth Muse

by Catherine Chung

Katherine, an Asian American math genius, is driven to achieve in a competitive, male-dominated field and solve the Riemann hypothesis, considered one of the greatest unsolved mathematical problems. That drive is rivaled only by her desire to solve the mystery of her family history. Bountiful in scope, fables, intellect, and heart, the novel is at times heart-wrenching.

3 The Favorite Daughter

by Patti Callahan Henry

This is a gorgeous, deeply affecting story about a family reunited because of the father’s failing health. After a 10-year absence, Lena Donohue returns to her South Carolina homestead and family-owned Irish pub. Still hurting from the betrayal of her fiancé and younger sister, she tries to embrace her family, including two adorable nieces. The novel is lyrical, engaging, uplifting, and real – forgiveness beckons all, even as secrets unravel.

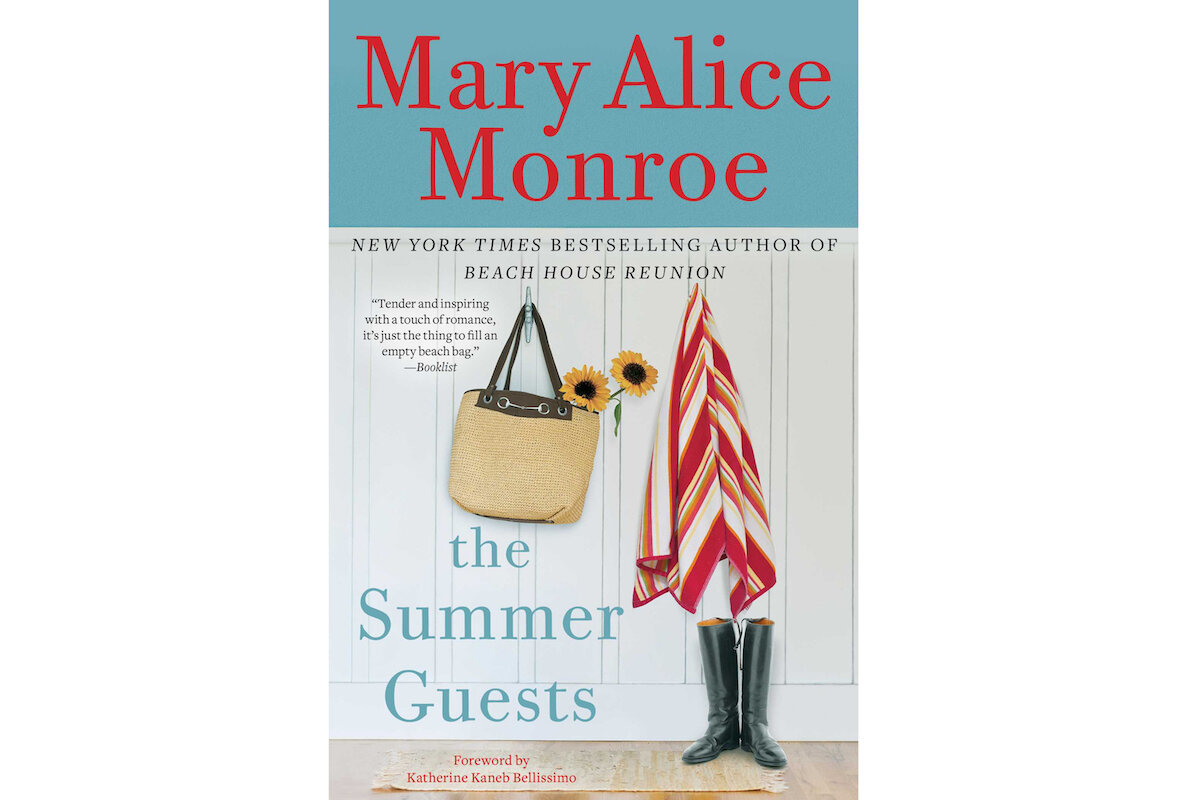

4 The Summer Guests

by Mary Alice Munroe

Hurricane Noelle is heading toward the southeast coast; under mandatory evacuations, friends, family, and even rescue dogs seek refuge at the horse farm of Grace and Charles Phillips in North Carolina. A whirlwind of fascinating personal storylines propels soul searching, forgiveness, and second chances.

5 Time After Time

by Lisa Grunwald

Set in New York’s Grand Central Station during the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, this thoroughly charming love story has a supernatural predicament at its center. Sunrises and sunsets that occur only a few times a year – a phenomenon known as “Manhattanhenge” – play a mysterious role in the love match of Nora, a plucky flapper, and Joe, the steady, kind railroad man she falls for.

6 Ayesha at Last

by Uzma Jalaluddin

Who among us doesn’t love a good update of “Pride & Prejudice”? Uzma Jalaluddin delivers with a satisfying romance full of wit and humor, set among a Canadian Muslim immigrant community navigating tradition and assimilation for its young men and women.

7 The Electric Hotel

by Dominic Smith

In 1962, a graduate student tracks down and interviews photographer Claude Ballard. In a series of flashbacks, Ballard reveals his early life as a silent film director, sharing with the student the canisters of film he’s stashed in the hotel room he calls home. This historical fiction about unrequited love between a director and his muse is chock-full of the history of the early film industry.

8 What I Stand On

by Wendell Berry

This two-volume set of Wendell Berry’s essays, published between 1969 and 2017, provides crucial insights about America’s environmental crisis and its pervasive causes. As he demonstrates throughout the work, “soil is the great connector of lives.” If we want healthy people and communities, we must take care of the land. Doing so is our most ancient, urgent duty, according to Berry.

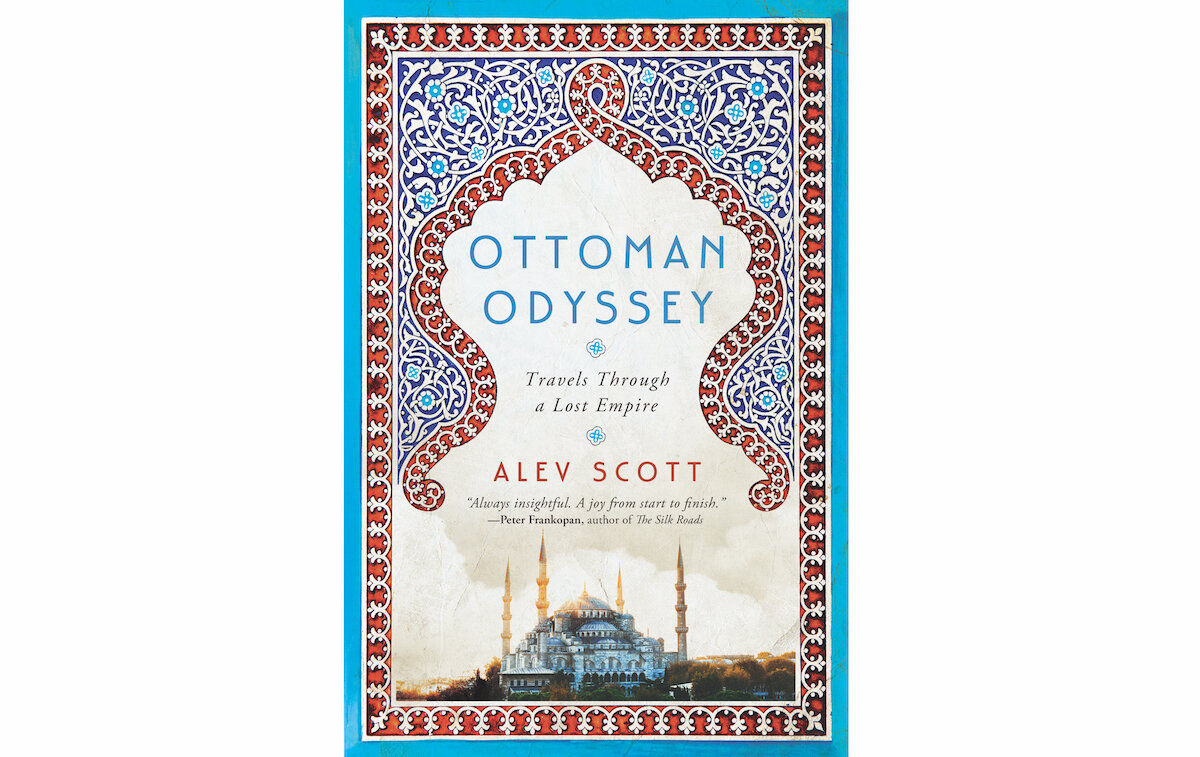

9 Ottoman Odyssey

by Alev Scott

Half-Turkish, half-British journalist Alev Scott roams through elements of the Ottoman Empire in this bright travel narrative. She laces history with footloose journeying and the result is a restless, kaleidoscopic, and chromatic portrait of a land in flux.

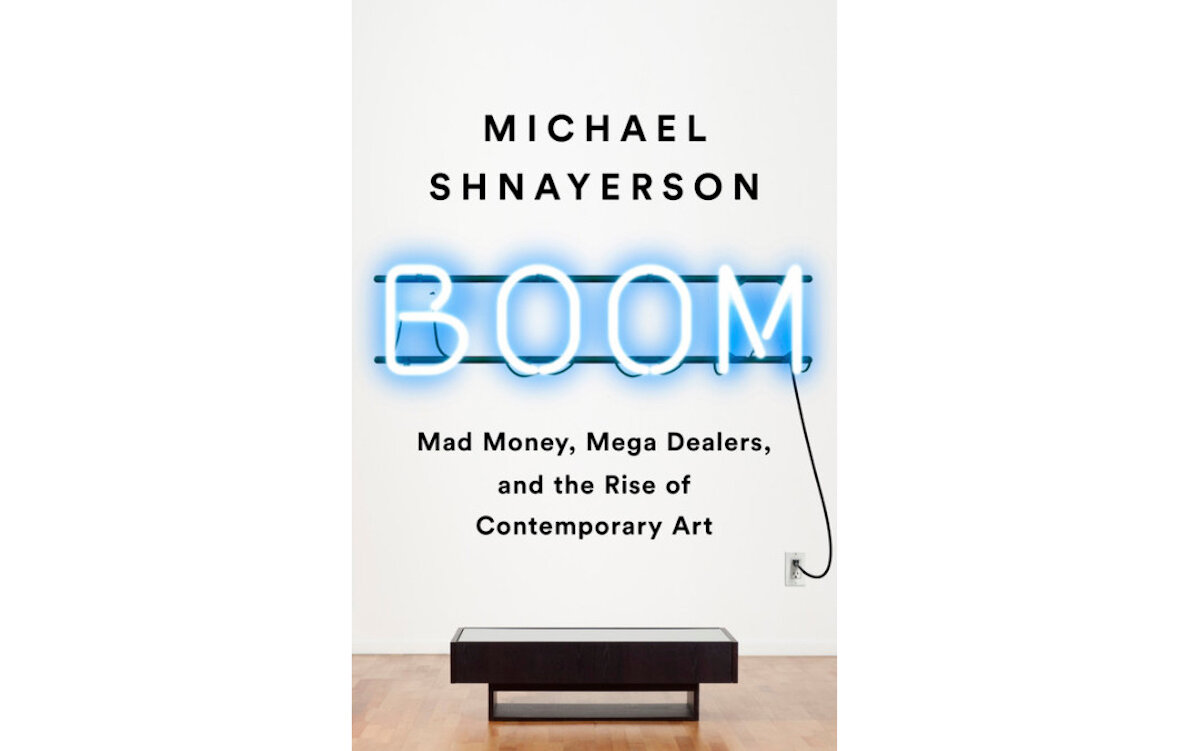

10 Boom

by Michael Shnayerson

Michael Shnayerson shows how contemporary art morphed from the passion of a few to a fashion for the ultrarich. Thanks to skyrocketing auction prices and four dominant dealers, contemporary works have become a hot commodity. The book charts the switch from a genteel circle of connoisseurs to a roiling shark tank of investors.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Centering a nation’s budget on ‘well-being’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Is a booming economy the only measure of the quality of life in a country?

That question has been under intense discussion for years. Critics have found financial measurements such as gross domestic product (GDP) inadequate.

In late May, New Zealand became the first country to design its budget around a specific set of measures of national “well-being.” Government spending must show it contributes to at least one of five national goals: better mental health (including fewer suicides), less child poverty, help for minorities (Maoris and Pacific Islanders), moving to a low-carbon economy, or adapting successfully to the digital age.

GDP, for example, may not reflect widening income inequality. “Growth alone does not lead to a great country,” notes Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. The goal, adds Finance Minister Grant Robertson, is to make New Zealand “both a great place to make a living, and a great place to make a life.”

Whether New Zealand has made the right choices for how to measure an improvement in well-being remains to be seen. But this tiny country’s big experiment with a well-being budget is likely to get a close look in capitals around the world.

Centering a nation’s budget on ‘well-being’

Is a booming economy the only measure of the quality of life in a country?

That question has been under intense discussion in recent years. Critics have found financial measurements such as gross domestic product (GDP) inadequate. Attempts have been made to find other ways of measuring the well-being of a nation’s people, such as the annual World Happiness Report and the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals.

In late May, New Zealand became the first country to design its budget around a specific set of measures of national “well-being.” Government spending must show it contributes to at least one of five national goals: better mental health (including fewer suicides), less child poverty, help for minorities (Maoris and Pacific Islanders), moving to a low-carbon economy, or adapting successfully to the digital age.

Growth in GDP is often used to measure the well-being in a country. And growing wealth and human well-being has been found to go hand in hand in some ways.

But GDP, for example, can’t reflect the widening income inequality that is troubling the United States and other countries. Is a rising GDP representing a better life for everyone – or only a privileged few? GDP can paint an incomplete picture.

New Zealand’s new well-being budget doesn’t ignore economic growth, notes Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. But “growth alone does not lead to a great country,” she says. Despite its strong economy her country still faces daunting social problems, including suicide, homelessness, family violence, and child poverty.

The goal of the well-being budget, adds Finance Minister Grant Robertson, is to make New Zealand “both a great place to make a living, and a great place to make a life.”

The budget is being criticized from both left and right. For those on the left, it fails to be radical enough; specifically, it fails to hike the capital gains tax, seen as a means to address income inequality. A member of the opposition center-right National Party has dismissed the budget as nothing more than a “marketing campaign” that will divert attention from facing future economic risks.

How do you measure happiness or well-being? Views differ on what Thomas Jefferson meant when he included the phrase “the pursuit of Happiness” in the Declaration of Independence as a natural right. Was the phrase merely a euphemism for the pursuit of wealth, as some suggest? Or did he see a natural yearning for other, deeper satisfactions that government must recognize?

Whether New Zealand has made the right choices for how to measure improvement in well-being remains to be seen. But its experiment can hold lessons for others. New Zealand may be a small, remote island nation of fewer than 5 million, but it is also a vibrant democracy that must mix a majority population that has European roots with a significant number of ethnic minorities, a challenge it shares with many other nations.

That’s why this tiny country’s big experiment with a well-being budget will likely get a close look in capitals around the world.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

When decisions feel beyond our control

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Kylie Sisson

With the need to decide the future relationship of the United Kingdom and the European Union extended for at least several more months, today’s contributor shares how she has been praying in response to the uncertainty surrounding Brexit.

When decisions feel beyond our control

A friend asked me recently if I prayed about Brexit (the process of the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union). “Sure,” I said.

But what does that really mean? Whenever I’ve been faced with uncertain and difficult choices, turning to God has always brought me peace beyond that of relying on my own or others’ opinions and provided the answer I needed. So in thinking about Brexit, it’s natural for me to pray in a similar way.

The Bible says, “Trust in the Lord with all thine heart; and lean not unto thine own understanding. In all thy ways acknowledge him, and he shall direct thy paths” (Proverbs 3:5, 6). This kind of prayerful trust isn’t fatalistic. It’s based on a conviction in the practicality of divine goodness that lifts us above relying on politicians or others to personally discern and do the right thing.

This conviction comes from recognizing God as infinite Mind, the source of all good, and “the all-knowing, all-seeing, all-acting, all-wise, all-loving, and eternal,” as “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy describes the Divine (p. 587). This turns our thought from ruminating on conflicting human opinions to listening for God’s unerring and clear direction. Trusting God to direct each step in infinitely wise and loving ways silences fear, quiets uncertainty, and brings a gentle reassurance that God, good, governs all, as Christian Science reveals.

The peace I’ve found from praying this way in my own life has led to answers to relationship, financial, home, and employment problems in ways I couldn’t have planned or predicted. Witnessing the impact such prayer has in my own experience shows me what is possible. And we can reach this same peace when praying for the world. We don’t need to be drawn into speculating about what might happen. We can know and trust that God’s government of all can have a healing impact on whatever situation we are praying about.

I don’t know how the important current national and international issues will be resolved. But my own experience tells me that when we understandingly trust God rather than leaning on personal opinion and knowledge – or “thine own understanding” – ways open up for progress to happen.

A message of love

Ford every stream

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Tomorrow, Francine Kiefer, our new West Coast bureau chief, will look at what it takes to break out of the second tier of Democratic presidential candidates. She’ll focus on California Sen. Kamala Harris, whose bid is a case study of the difficulties.