- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In historic shift, Botswana declares homosexuality is not a crime

- US farmers caught between a flood and a trade war

- After promising start, Kamala Harris looks for ways to break through

- Can religious tolerance help an aspiring Muslim power?

- Readers respond to gun violence. Their reactions may surprise you.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Big Papi strong

David Ortiz was an impressive ballplayer. He made history again and again in Fenway Park. But the act that has defined his legacy, for me, wasn’t when he swung a bat.

It was a 54-word ad-libbed speech shortly after the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013. For a week, the city and suburbs had experienced fear and lockdowns as police chased suspects. The bombers had been caught the night before. But the wounds were still raw when Big Papi stepped onto the field before the April 20 game.

“All right, Boston,” he said. “This jersey that we wear today, it doesn’t say ‘Red Sox.’ It says ‘Boston.’” He thanked the police and politicians, and said: “This is our [expletive] city. And nobody’s going to dictate our freedom. Stay strong.”

At that moment, his influence went beyond a sport or even a city. No. 34 gave voice to a feeling of defiance. It was a fierce rebuke to fear.

“Big Papi was saying what he felt about Boston – ‘Boston Strong’ – and how a terrorist attack was not going to change the basic spirit of that city,” then-President Barack Obama said in a speech in 2016. “At that moment, he spoke about what America is.”

As you may have heard, the retired slugger is recovering from a gunshot wound reportedly from a hit man in the Dominican Republic. The Red Sox flew him to Boston Monday night for medical care. He’s back gathering strength from a city that he once helped carry.

Big Papi strong.

Now to our five selected stories, including testing times for American farmers, the rise of tolerance in Africa and the Middle East, and how our readers are responding to gun violence.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In historic shift, Botswana declares homosexuality is not a crime

Our reporter gives us a front-row seat to African history today, in a Botswana courtroom where justices overturned a colonial law against homosexuality – significant for cheering not only activists sitting beside her, but also advocates across the continent.

On a bright winter day in Botswana’s capital, a panel of three High Court judges unanimously struck down a colonial-era law criminalizing homosexuality, becoming the second court in African history to do so.

“A democratic nation is one that embraces tolerance, diversity, and open-mindedness,” said Judge Michael Leburu, reading from the court’s ruling Tuesday. “We have determined that it is not the business of the law to regulate private consensual sexual encounters” between adults.

Botswana, like more than half of the countries that criminalize homosexuality, inherited its law from Victorian England. Momentum has been building to repeal those laws, arguing that they were imposed on societies without consultation.

For many supporters of decriminalization, the idea that their culture was against homosexuality was always a simplistic one. Though their society contained elements who believed homosexuality was a sin, it also contained many people who – whether or not they’d heard of a thing called “gay rights” – had loved and accepted them as they were.

“I was never taught to hate myself,” says Letsweletse Motshidiemang, who brought the lawsuit as a college student.

“I did this so people like me don’t need to feel like who we are is a crime.”

In historic shift, Botswana declares homosexuality is not a crime

When Letsweletse Motshidiemang was growing up in a village in northern Botswana, there wasn't exactly a name for what he was. Certainly no one ever used words like gay, or queer, or LGBTQ. In fact, no one called him much of anything at all. And in that silence, he says, was a quiet acceptance. “People knew I was different, but I was surrounded by people who loved me,” he says. “I was never taught to hate myself.”

So it wasn’t they who first suggested he might have to change who he was. “It was the laws,” he says. Men like him, he learned as a teenager, couldn’t get married to other men. They couldn’t start families. Their very existence, in the eyes of the police and the courts and the constitution in Botswana, was a crime.

And so in 2016, when he was 21, Mr. Motshidiemang approached a law professor at the University of Botswana, where he was a student, and asked for his help to challenge Botswana’s “carnal knowledge” law, a colonial-era prohibition on gay sex.

At the time, he wasn’t an activist. He’d never been to pride parades or even had a close gay friend. He was a bookish literature student who dreamed of moving home after graduation to work as a primary school teacher. He had nothing behind him but the conviction that the law was wrong, and the way he wanted to live was right.

“I’m just someone who takes pride in who he is,” he says. “I did this so people like me don’t need to feel like who we are is a crime.”

And three years later, on a bright winter day in Botswana’s capital, a panel of three High Court judges unanimously affirmed that belief.

“A democratic nation is one that embraces tolerance, diversity, and open-mindedness,” said Judge Michael Leburu, reading from the court’s ruling Tuesday morning. “We have determined that it is not the business of the law to regulate private consensual sexual encounters” between adults.

Ten miles away, in the one-room brick house where he lives on the fringes of Gaborone, Mr. Motshidiemang, now 24, began to weep. “Of course I wanted to win, but I didn’t expect it,” he said through tears on the phone. “I did it just because I felt it was something I had to do for my community.”

And for activists who gathered at the courthouse and those watching from around the continent, the moment was bigger still. For only the second time in history, an African court had struck down a national law criminalizing homosexuality, cracking open a door for other countries to follow their lead. (South Africa’s Constitutional Court decriminalized gay sex in 1998.)

Legacy of colonial era?

Botswana, like more than half of the 70-some countries that criminalize homosexuality worldwide, inherited its law from the British Empire. In recent years, momentum has been building globally to repeal those laws, which prohibit sex “against the order of nature,” arguing that they were imposed without consultation in societies that had sometimes made space for a range of sexualities in the past. And in cultures where many opponents of LGBT rights see them as “Western imports,” having regional precedents is especially key, legal activists say.

“We’ve seen an increasing trend of countries drawing on other countries in their region,” or in other Commonwealth countries, says Neela Ghoshal, senior researcher in the LGBT Rights program at Human Rights Watch. “So I think this ruling is going to inspire activists around the continent and in other parts of the world as well. The language of the ruling in Botswana is so clear. It makes really crystal clear that people’s private sexual behavior and morality is not the business of the state.”

Last year, India struck down its own “order of nature” law, with the judges writing that it had been “irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary” and that “history owes an apology to members of the community for the delay in ensuring their rights.”

“We’ve been stuck with these provisions when [the British] have long discarded them,” says Tshiamo Rantao, the lawyer for the Lesbians, Gays & Bisexuals of Botswana (LEGABIBO), an advocacy group that joined the case as a friend of the court. He notes that while Botswana’s laws punish homosexuality with up to seven years in prison, it was decriminalized in England and Wales half a century ago.

But last month, a court closer to home, in Kenya, voted unanimously to uphold that country’s prohibition on gay sex, leading many to worry that momentum for global repeal had been scuttled.

In that case, indeed, the Kenyan High Court cited a 2003 decision from Botswana, Kanane v. The State, which found that “the time has not yet arrived to decriminalize homosexual practices.”

“Gay men and women do not represent a group or class which at this stage has been shown to require protection under the Constitution,” the Botswana court explained at the time.

On Tuesday, however, the three-judge panel returned to that argument, and this time, found it lacking.

“As society changes, the law must evolve,” explained Judge Leburu, speaking on behalf of himself, Abednico Tafa, and Jennifer Dube, the three judges who heard the case. The law in Botswana, he said, was a “British import” and had been developed “without consultation of local peoples.”

It’s “about time Botswana sheds this colonial legacy and interprets its own humanity,” says Tshepo Ricki Kgositau, a transgender woman who in 2017 successfully challenged at this same court to have the gender marker on her driver’s license changed from male to female.

Ms. Kgositau’s case, indeed, was part of a wider strategy of LGBT rights groups here to incrementally challenge discriminatory laws in order to create precedent.

“We had to set the courts up to change their minds,” says Anneke Meerkotter, litigation director for the Southern African Law Centre, which provided legal support to LEGABIBO. “When you rush to court and the court isn’t ready, it can actually set you back years in your fight.”

The case in Botswana is of particular significance for African legal activists, who have long faced the accusation that homosexuality and its allies are an imported Western threat to local values.

“As things stand, Botswana is being forced to abandon its moral values. The courts should be conservative and measured,” explained Sydney Pilane, the lawyer for the state, in a hearing earlier this year, arguing that people in Botswana had always opposed homosexuality.

But in Tuesday’s case, the judges were unequivocal. “Cultural practice cannot justify any violation of human rights,” said Judge Leburu.

For many supporters of decriminalization, including Mr. Motshidiemang, the idea that their culture was against homosexuality was a simplistic one, anyway. Many people have long loved and accepted them, whether or not they’d heard of a thing called “gay rights.”

“It’s not that most people in this country hate us,” Mr. Motshidiemang says. “It’s just that the people who hate us are very loud.”

What comes next?

No sooner had the case concluded than many began to ask what would come next. Would Botswana follow South Africa’s lead and legalize gay marriage? Would there be backlash, now that the law had jumped out in front of public opinion? (A 2016 Afrobarometer poll showed that only 43% of people in Botswana “are not opposed to having homosexual neighbors.”)

“We won’t fool ourselves. We know a change of law doesn’t mean the end of discrimination,” says Anna Mmolai-Chalmers, who heads LEGABIBO, the gay rights group. “But the law also has power.”

Around her, on the steps of the High Court, supporters draped in rainbow flags clung to each other, giddily posing for selfies and crying.

Soon, they say, the state will likely bring an appeal, challenging their victory. There may be another day in court, and likely more after that, too.

But for today, for now, what they’d done felt like enough. They had won.

US farmers caught between a flood and a trade war

Patience and resilience are fundamental to farming. But at a time when the weather and political policy are creating uncertainty, American farmers are being tested.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

This isn’t the usual spring planting season. Wet weather has delayed planting for grain farmers on a scale not seen in decades. Some fields will simply go unplanted, as farmers weigh whether to risk crop failure or settle for insurance payments worth about half what they would normally receive per acre.

There’s another reason for concern, too: uncertainty over federal policies that affect their markets. A trade war with China – a key market for soybeans – has flared up. Then President Donald Trump used a tariff threat to pressure Mexico to tighten border security.

“They understand what he’s trying to do. ... Farmers are the best patriots in the country,” says Scott VanderWal, a farmer and president of the South Dakota Farm Bureau, an advocacy group. But he says “there comes a time when we all have to keep our businesses and farm operations together. ... Farmers are getting impatient.” For now the risk of trade conflict with Mexico seems to have receded. But as many of his cornfields go unplanted, Mr. VanderWal says the threat was “not helpful.”

US farmers caught between a flood and a trade war

Standing a few feet from a pool of water in his field, on a strip of now-crusted mud where no corn plants are shooting up, Scott VanderWal contemplates a question: Which makes farming more uncertain these days: the weather or White House policy?

“That’s a hard question,” says Mr. VanderWal, a farmer and president of the South Dakota Farm Bureau, an advocacy group. “I would say they are both about the same.”

Hit with wet weather that has delayed spring planting on a scale not seen in decades, many farmers from here in Volga, South Dakota, to Ohio are making the difficult decision not to plant certain fields this year – to settle for insurance payments worth about half what they would normally receive per acre, rather than plant and risk an early frost.

At the same time, federal policy added a new layer of uncertainty and even alarm among agricultural producers. Slowly, these issues are being resolved – from disaster aid to trade talks – but not before exposing waning patience among many in farm country with the administration’s unpredictability.

“Farmers are grumpy,” says Norman Brugger, a rancher and seed salesman in Albion, Nebraska. “I have listened to people talk, coffee-shop talk ... and I have heard some guys who are changing their minds” about President Donald Trump.

Part of rural dissatisfaction stems from the difficult spring. Normally, this time of year, Corn Belt states like Indiana and Ohio would have all but finished corn planting. Instead, they’ve got two-thirds or less planted, according to the crop progress report the U.S. Department of Agriculture released Monday. South Dakota is in the same boat – 64% planted – but because the risk of frost comes a little earlier here, the window is closing fast.

The silver lining is that, in the quirky economics of agriculture, a poor corn crop could be good for farmers. Already, corn prices have surged to three-year highs. Farm income is likely to rise this year, after several years of decline, says Scott Gerlt, an agricultural economist with the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri. Even farmers with poor yields may do better, because crop insurance provides payments for those who don’t plant at all as well as those who have a reduced yield.

How well they fare will depend in part on a long-delayed $19.1 billion disaster aid package that the president signed Thursday, after trying for months to limit how much would flow to Puerto Rico for recovery from Hurricane Maria. The measure, which includes $3 billion in aid for agriculture, should be of special help to Georgia and Florida farmers who have waited since last October to find out if federal aid would help ease their severe losses from Hurricane Michael. But economists say the money is too little to provide much help for Midwestern farmers who can’t plant. The regulations for distributing the money still haven’t been written.

Farmers breathed another sigh of relief Friday after Mr. Trump announced an immigration deal with Mexico, forestalling his threat of imposing 5% tariffs on imports from America’s largest trading partner. The tariffs would have hit the auto industry hardest, but also would have raised consumer prices on a range of goods from Mexico, including fruits and vegetables.

Farmers also feared U.S. tariffs would trigger Mexican retaliation on imports from the United States. Mexico is the second-biggest export market for U.S. agricultural goods after Canada. But other trade actions are still raising concerns in farm country.

For example, Mr. Trump’s aggressive negotiations with China, which include tariffs on Chinese goods and countertariffs from China, have hurt soybean exports and swelled U.S. stockpiles, which have caused prices to fall. In the short term, most of those soybeans will get sold to other nations if the Chinese market disappears. But the longer the U.S.-China standoff continues, the more other nations will expand production and displace U.S. sales around the world.

By standing firm against unfair Chinese trade practices, Mr. Trump has gotten a pass from many farmers, says Mr. VanderWal, who is also vice president of the American Farm Bureau Federation, a conservative farm advocacy group in Washington with strong lines of communication with the administration. “They understand what he’s trying to do. ... Farmers are the best patriots in the country. But there comes a time when we all have to keep our businesses and farm operations together. ... Farmers are getting impatient.”

If the China trade impasse gets grudging acceptance, the president’s sudden shifts on Mexico have not. The U.S. and Mexico had been moving toward ratifying a new North American trade pact, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), when Mr. Trump suddenly tweeted late last month that he would impose 5% tariffs on Mexican imports – which would eventually rise to 25% – if its government didn’t strengthen border security against migrants making their way to the U.S. Then on Friday Mr. Trump tweeted that the two nations had signed a last-minute deal to avert the tariffs, which he had threatened to impose on Monday.

Subsequent reporting from The New York Times suggests that much of the deal had already been reached in secret negotiations earlier this year, while the administration contends that stronger provisions and an important and unnamed new provision were not reached until the threat of levies had been imposed. He also tweeted Sunday that if there is not cooperation on the border from Mexico “we can always go back to our previous, very profitable, position of Tariffs.”

It is this uncertainty – which the president appears to thrive on – that exposes growing concern over some of the president’s tactics. This does not signal a political break with Mr. Trump. Many rural Republicans applaud his whatever-it-takes approach to handling problems, including immigration.

When a country like Mexico isn’t budging on an issue, “we need to get their attention,” says Verlin Janssen, a city councilman for Gothenburg, Nebraska, and a retired businessman.

Others quietly chafe at the uncertainty created by Mr. Trump’s negotiating style. Threatening Mexico with tariffs was “not helpful,” says Mr. VanderWal. “Get USMCA passed. It would give the Trump administration more credibility when negotiating with other countries.”

After promising start, Kamala Harris looks for ways to break through

In the crowded 2020 field, candidates such as California Sen. Kamala Harris are struggling to stand out. Our reporter looks at the causes and whether the coming debates will shake up the race.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Kamala Harris connects well in person and on camera. At a campaign swing through California, she hugged, sashayed, and smiled her way through events. Her delivery is crisp and on point. Yet since launching her presidential campaign to great fanfare and an enormous crowd of 20,000 in Oakland, California, in January, she has been stuck in the lower tier of candidates. Recent polls show her support at or below 10%.

The California senator’s struggles reflect the unwieldy nature of this historically large Democratic field. With 24 hopefuls traipsing around the early voting states and showing up at cattle calls, making an impression – even for the most promising contenders – is proving to be a real challenge. Senator Harris has also been faulted for “pandering” to the left and failing to communicate a core message. But for many Democratic voters, it may come down to the bottom line: Who can beat President Donald Trump?

“I think Kamala Harris will compete well. But a lot will depend on whether Democrats think it’s less risky to nominate an old white guy instead of a younger woman of color,” says Dianne Bystrom, a longtime observer of presidential campaigns and women in politics. “It may come down to that.”

After promising start, Kamala Harris looks for ways to break through

Kamala Harris has always been a trailblazer. As the daughter of immigrant parents – her mother came from India and her father from Jamaica – she was the first woman elected (twice) as California’s attorney general, and the second African American woman elected to the United States Senate, which she entered two years ago. From the moment she got there, the chattering classes began speculating about White House ambitions.

Those lofty expectations seemed justified when she launched her presidential campaign in Oakland, California, in January, drawing an enormous crowd of about 20,000 people. She’s since brought in some big endorsements, including California Gov. Gavin Newsom, and an impressive fundraising haul.

What Senator Harris hasn’t been able to do of late is break past 10% in national polls.

The California senator’s struggle to gain momentum reflects the unwieldy nature of this historically large Democratic field. With 24 hopefuls traipsing around the early voting states and giving back-to-back speeches at cattle calls like the recent Democratic Hall of Fame dinner in Iowa and the party convention in California, making an impression – even for the most promising contenders – is proving to be a real challenge.

Senator Harris has also been faulted for “pandering” to the left and appearing overly cautious on the trail. In a field with relatively few big policy differences between them, observers say it’s vital for candidates to communicate core beliefs and a clear sense of identity. But ultimately, for many Democratic voters, it all may come down to the same bottom line: Who can beat President Donald Trump?

“You have to have a message that resonates,” says Dianne Bystrom, a longtime observer of presidential campaigns and women in politics.

“She’s got great communication skills,” Dr. Bystrom says of Senator Harris, but “I don’t think she’s as specific about her message as [Massachusetts Sen.] Elizabeth Warren is.” She adds that Senator Harris needs to “further define herself.”

Second, but not first

Of course, it’s early yet, and the upcoming debates – the first of which will take place at the end of this month – could offer many second- or third-tier candidates a chance to break out of the pack. Former Vice President Joe Biden is widely regarded as a weak front-runner, and most political observers believe the landscape could shift substantially before Democratic voters start casting ballots early next year.

Jim Messina, former President Barack Obama’s campaign manager, famously commented on MSNBC in April that if Senator Harris were a stock, he’d “buy her” – in other words, seeing a future rise as a good bet.

In Iowa, the latest Des Moines Register/CNN poll has Senator Harris well behind Vice President Biden, as well as behind Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, Senator Warren, and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg. Yet it also found her tied with Senator Warren as the top second choice of Iowa Democrats. Heading into the caucuses, that can be a sign of hidden strength.

Still, being voters’ second choice is not the same as being their first choice.

At the recent California Democratic convention in San Francisco, James Smith, a firefighter from Long Beach, says Senator Harris is “great” but “not for 2020.” He’s standing behind the International Association of Firefighters endorsement of Vice President Biden. “He’s a friend of labor,” says Mr. Smith. “Joe’s our guy.”

Alex Núñez, of Mountain View, raves about Senator Harris’ performance interrogating Attorney General William Barr at a Senate hearing last month, an exchange that went viral on social media. As a former prosecutor, “she has a unique skill set,” he says. But he doesn’t envision her as president – more like a future attorney general who might someday prosecute President Trump.

“She’s forceful,” agrees Roberta, a retiree from New York who says she does not want her last name used for fear of becoming the target of a Trump tweet. Coming out of an event for Senator Sanders in Pasadena, California, she says she’s a fan of Senator Harris and finds her “very believable.” Still, she can’t commit to backing her. “I’m in a quandary. I don’t know who to vote for.”

Crisp and on point

Senator Harris connects well in person and on camera. At a recent campaign swing through California, she hugged, sashayed, and smiled her way through events, continually throwing the praise back at her supporters – whether they were immigrant activists or union members. Her delivery is crisp and on point.

When a man jumped onstage at a MoveOn forum in San Francisco and grabbed the microphone from her, the former district attorney kept her cool, calmly walking away as others – including her husband – hustled the man offstage.

In her stump speeches, she focuses on pocketbook and equality issues, particularly for women and women of color. She proposes a monthly tax credit of $500 for families earning less than $100,000 a year; a big boost for teacher salaries; and equal pay for women – with companies on the hook to prove they comply or else pay a fine.

Yet having detailed policy positions is not the same as having a message, warns Bill Carrick, a Democratic strategist in Los Angeles. “The message has to be part of who you are, what you stand for, what you believe in, what your values are.”

Mr. Carrick describes the revolutionary Senator Sanders as a “classic stand-up-for-the-little-guy, a lefty, with policy underneath it all.” Similarly, Senator Warren has the “total package” – someone who belongs in the hall of fame of policy wonks in her fight against corporations and who is also emotionally driven by this fight.

Former Vice President Biden is another strong persona, “somebody who can bring us together, get things done, and most importantly, win.”

When asked about Senator Harris, Mr. Carrick pauses. “I’m not sure what her message actually is. And that’s really a challenge.”

Lately, she has been trying some new approaches. At the California Democratic convention, she leaned much more into an anti-Trump message, built around a series of “truths” about President Trump’s “lies” and calling for the start of impeachment proceedings.

At the Iowa dinner last weekend, she furthered this line of attack – emphasizing her prosecutorial chops and portraying President Trump as having “defrauded” the American people when it comes to health care, taxes, and national security.

“I am prepared to make the case for America and to prosecute the case against Donald Trump,” the former district attorney said.

Recalibrating her pitch

The rhetorical shift may be in response to critics who’ve been arguing she ought to present herself as a pragmatist. Her main competitor in the race is not Senator Sanders, these critics say, but Vice President Biden. They argue that she made a serious error in pandering to the left, pulled there in part by her sister, Maya Harris, her progressive campaign chairwoman.

Senator Harris has supported liberal causes such as Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, and the decriminalization of sex work, and she has indicated an openness to reparations for slavery, as well as having a “conversation” about voting rights for violent felons. In several cases, she’s later had to walk back her comments or try to clarify.

It is a pattern similar to her record on some issues in California, when she changed positions on the death penalty and stepped back from her controversial policy to punish parents for their children’s truancy, which resulted in a few parents going to jail.

David Axelrod, a former top adviser to President Obama, has criticized Senator Harris for being overly cautious in answering questions – trying to have things both ways. He told the Los Angeles Times that “she’s a brilliant person,” but “what we’ve learned so far is that she’s great at asking questions but timid at answering them.”

Senator Harris’ fans are fervent in their support, and say she is facing strong winds of sexism and racism – a point that Dr. Bystrom, who’s now retired from Iowa State University in Ames, also makes. After Hillary Clinton lost to President Trump in the Electoral College, the possibility of losing again is making some Democrats “very nervous” about nominating a woman, and a woman of color, Dr. Bystrom believes.

“I think Kamala Harris will compete well. But a lot will depend on whether Democrats think it’s less risky to nominate an old white guy instead of a younger woman of color,” she says. “I think it may come down to that.”

A deeper look

Can religious tolerance help an aspiring Muslim power?

The UAE is an emerging political, military, and economic leader in the Middle East. We wondered: Will its core value of interfaith tolerance spread?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak, a member of the United Arab Emirates’ ruling family, drops the word “tolerance” so frequently it sounds like a mantra. His grandfather offered land for the first church in the Emirati capital as the ruler of Abu Dhabi more than a half-century ago. “We have a history of living alongside the other and respecting the other, and we don’t want to take this for granted,” Sheikh Nahyan says.

Owing to the arrival of migrants from across the world, the UAE has become a seamless meeting place of faiths and cultures. And it is billing itself as an interfaith leader, having declared 2019 to be a national “year of tolerance” that was headlined with a visit by Pope Francis in Abu Dhabi in February. Its neighbors and close allies are less tolerant. Saudi Arabia has banned the building of churches or temples.

As the UAE emerges as a leading military and economic power in the region, its leadership is committed to pushing a friendly, tolerant image to the world. Showing it is open to other religions is not only good for business; it also sends the message that the UAE shares values with its Western allies.

Can religious tolerance help an aspiring Muslim power?

Indian women in saris carefully place candles at an outdoor grotto of the Virgin Mary and kneel in prayer as couples from Uganda and Nigeria pour into the nearby chapel.

Arab Chaldeans, Maronites, and Latin Catholics laugh together as they enter a unified Arabic-language Catholic church service; Egyptian and Sudanese families gather in front of the next-door Coptic church; and English expats head into the Anglican church.

Pakistani bus drivers snap pictures with their phones as 15 Filipino brides and grooms pose for wedding photos outside St. Joseph’s Church ahead of their mass wedding.

All the while, Filipinos line up for mashed purple yam cakes and polvorón shortbread at an outdoor bake sale in the church courtyard, with the Islamic call to prayer from the neighboring Jesus Son of Mariam Mosque ringing out overhead.

This is not an international festival; it’s a Sunday in Abu Dhabi.

Owing to the arrival of migrants from across the world, the collection of tiny Arab Emirates at the tip of the Persian Gulf – an international financial powerhouse and a growing diplomatic and military power in the Arab world – has become a seamless meeting place of faiths and cultures.

The United Arab Emirates is also billing itself as an interfaith leader, having declared 2019 to be a national “year of tolerance” that was headlined with a visit by Pope Francis in Abu Dhabi in February – the first-ever papal visit to the Gulf in the history of the Roman Catholic Church.

But even as this oil-rich country’s rulers promote harmony, the country’s ultraconservative laws strictly forbid these faithful from seeking to convert Muslims or from publicly displaying crosses. Its neighbors and close allies promote an austere interpretation of Islam with less tolerant attitudes toward other organized religions. Saudi Arabia, its closest ally, has banned the building of churches or temples.

The lure of the Islamic State group remains for some in the region, while an uneasy gray area exists between violent extremist movements and conservative Muslim televangelists who dominate Gulf airwaves and are suspicious of other faiths.

So the question remains: Can this petrodollar expat haven of sleek skyscrapers and polished public-relations campaigns truly be a beacon for interfaith tolerance in the Muslim Gulf and the wider Middle East?

More is at stake than a simple PR campaign.

As the UAE emerges as a leading power in the region, its leadership is committed to pushing a friendly, tolerant image to the world and its Western allies.

Showing it is open to other religions is not only good for business with the West, India, and Asia; it also sends the message that the UAE shares values with its Western allies. Saudi Arabia’s inability to do so has led it to become a pariah in many capitals.

As the UAE steps up its military and political involvement across North Africa, the Arab world, and farther afield, Abu Dhabi believes that the best way to head off criticism or opposition is to show that Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jews are all welcome to worship on Emirati soil.

Emirates of migrants

The UAE’s history with non-Muslim faiths is rooted in the humble beginnings of the young country and is part of the story of its rise from poverty into a global economic power.

Christianity, Hinduism, and Sikhism all had a foothold in the Emirates and were communities before the Emirates gained independence and entered the United Nations in 1971. The communities grew in size as the UAE’s oil industry absorbed influxes of expatriate engineers, administrators, and oil rig workers.

When oil was discovered here in 1958, decades before petrodollars filled their coffers, the pre-independence Emirates were served by few schools or basic medical facilities. Churches and foreign missionaries helped the UAE to modernize.

In 1960, American Christian missionaries established the Oasis Hospital in the town of Al Ain. They served the ruling families and revolutionized prenatal and neonatal health in the Emirates, cutting infant mortality rates from a staggering 50% to 5% within a few short years.

In 1967, the Catholic Church opened St. Joseph’s School, Abu Dhabi’s first private school, and a year later St. Mary’s high school in Dubai.

The social outreach was noticed by the ruling families, and the appreciation is still felt today.

“The government here is grateful to Christians, as Christians contributed to the development of the country and have proven to be trustworthy,” says the Rev. Gandalf Wild, vice secretary of the Apostolic Vicar of Southern Arabia based in Abu Dhabi.

As the UAE shifted its focus to becoming a global economic hub at the turn of the 21st century, its expatriate community exploded to some 8 million, attracting workers from across Asia, Africa, North America, and Europe.

Expatriates now outnumber Emiratis 4 to 1. In Dubai there are more than 40 churches and dozens more Christian denominations that share chapels, a large Sikh temple, a Buddhist temple, and two Hindu temples, and several informal Jewish prayer groups meet in rented office spaces or apartments. A cornerstone for a new Hindu temple was laid in Abu Dhabi in April.

Different faith communities and cultures work together and pray side by side to the point that they have become indispensable to one another. All find a shared community in prayer.

Patriarchs and Vishnu

At St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Abu Dhabi, it’s Bible study night, and men and women from the Philippines, India, Uganda, and elsewhere have gathered, sitting in lines of folding chairs, a large wooden cross hanging above.

The diverse group is continuing an “Introduction to the Patriarchs” lesson, skimming through Genesis 15 through 22, stopping at Abraham’s preparations to sacrifice Isaac.

“We come from all over the world and speak different languages, but we are united in our love for our Lord,” says Lawrence, a student.

Coexistence is also evident at the Hindu and Sikh temples at Bur Dubai, buried in the heart of the port city’s mazelike historic souk near the seaside.

Stairs lead up to the second floor of the converted shop, where Hindu shipyard porters and CEOs pray at shrines for Shiva and Krishna; others continue to the third floor, cover their hair, and enter the Sikh temple, where a trio of men plays a calming, trancelike kirtan song on the stringed dilruba and drums.

Linking the two temples is a small, open-air kitchen by the stairway where Sikhs provide small meals of pilaf and lentils to all – Hindu, Sikh, and visitor alike.

“We pray at the temple each day; we put up lights for Diwali,” says Priya, an Indian national who has lived in the UAE for 10 years, as she leaves the temple. “It is like we are back home, but we get to share it with others who have no idea of our religion.”

Several prayer-goers stop at a small, street-level shop next to the Hindu and Sikh temples. It offers a rest stop for worshippers to place their sandals, strings of flower necklaces, and a counter of ready-made food offerings of bananas, apples, oranges, milk, and sweets on plastic-foam plates to place at the shrines.

The owner, Ahmed Mohammed, is a Shiite Muslim. Originally from Iran, Mr. Mohammed says he sees no contradiction in running a store catering to his neighbors and friends of 25 years.

“We all come from different places, but we are all one people here in Dubai. We support one another and help one another,” he says as he sells a prasadam plate to an Indian couple. “These values are present in all religions, whether Islam, Hinduism, or Sikhism.”

Breaking bread

Solidarity is served on a plate at Gurunanak Darbar Sikh Temple, the largest Sikh temple in the Arab world.

The ornate three-story temple stands across from Catholic, Anglican, Orthodox, and evangelical churches on a plot of land donated by Dubai ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashed al Makhtoum. It’s in the Jabel Ali area on the outskirts of Dubai, a few miles away from one of the largest worker camps in the Arab world.

The temple entrance leads to its langar, a gleaming, ultramodern 18-hour-a-day community kitchen with a catering staff on hand to provide three meals for 1,500 people each day. On Fridays, the temple feeds some 10,000 visitors.

The temple, completed in 2012, does not only provide for the Sikh community; Muslim, Hindu, and Christian factory and shipyard workers from Asia and across the world also rely on this temple for their daily meals. During Ramadan, the temple provides iftar meals for Muslims.

With an estimated 50% of its visitors non-Sikhs, the temple even dedicated a separate prayer room for visitors to pray and meditate, whatever their faith.

“Anyone can come here and venerate Allah or the Virgin Mary,” says Rajdeep Singh, the Gurunanak Darbar hospitality manager, as he opens the door to the guest prayer room. “This is not only a Sikh temple; this is a temple for all humanity. We believe humanity is the first religion.”

At the temple’s langar kitchen and eating area, men in fitted suits and crisply starched oxford shirts sit cross-legged on a long carpet next to workers with cement-stained jeans, 70-year-old matriarchs, and 7-year-olds, over plates of lentils, yogurt, vegetables, and rice pudding.

Worshippers say the religious tolerance in the Emirates has had social implications as well, bringing together those on vastly different rungs of the UAE’s pulsing, global economy who would otherwise never meet – from the brick-layers to the billionaires.

“When you walk into this temple or a church, money, title, positions are all dissolved,” Sanjay Kalwani, an Indian national who works in shipping, says as he and his wife, Sabna, sit down for plates of rice and lentils following an evening prayer at the Sikh temple.

“A billionaire CEO will pray and eat right next to a factory worker, and no one gets special treatment. We are all praying away from our homes, and in this interfaith community, we all share a common need.”

No proselytizing, no politics

But to conform with Islamic norms, faith groups also face limits.

Under Emirati law and a long-standing unspoken arrangement with the ruling family, Christian, Hindu, and Sikh religious groups do not proselytize or attempt to convert Muslims – a criminal act in the UAE. Apostasy by Muslims is punishable by death under the law, although there is no known legal case or prosecution in the UAE’s history.

Due to Islam’s ban against idolatry, Hindu temples were previously required to place images, rather than physical idols, in their shrines.

Human rights watchdogs say religious freedoms for non-Muslims in the UAE are by and large respected. A law bans discrimination on the basis of religion, and the government does not require faith groups to register or be licensed.

The key, church and temple leaders say, is “no politics.”

Religious leaders and communities here do not step into politics or even comment on decision-making. Foreign workers and expatriates refrain from discussing or criticizing Emirati laws, policies, or the ruling families in public.

The strict separation between worship and politics has fostered a harmonious relationship not only between the Emirati state and religious leaders, but also among the various faith groups themselves, whose leaders say they are more than happy to keep it this way.

But if the world’s religions are welcome, Emirati authorities have been less lenient with variations of Islam, human rights advocates say.

Any deviation from the state-sponsored Sunni Islam is viewed as a direct challenge to the state itself.

“There is no room whatsoever for any interpretation of Islam in the UAE other than their own,” says Hiba Zayadin, UAE researcher at Human Rights Watch. “As soon as you are out of step or criticize the state’s definition of moderate Islam, you are in trouble.”

Wary of the Muslim Brotherhood, which challenges the Gulf monarchies’ grip on power, the UAE has jailed Brotherhood sympathizers as terrorists and discourages various strands of Sunni and Shiite Islam from holding public displays of worship.

Rising tide of tolerance?

In 2017, to promote the UAE’s interfaith outreach at home and across the region, the Emirates created the world’s first “Ministry of Tolerance.”

It is headed by Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak, a member of the ruling family who drops the word “tolerance” so frequently it sounds like a mantra. His grandfather, Shakbut Al Nahyan, offered land for the first church in the Emirati capital as the ruler of Abu Dhabi more than a half-century ago.

“We have a history of living alongside the other and respecting the other, and we don’t want to take this for granted,” Sheikh Nahyan says. Noting the presence of extremist groups elsewhere in the region, he adds, “We have to protect future generations from intolerance.”

The UAE’s leaders are confident their model can encourage a change of approach in the Gulf.

“After the pope’s visit, Saudi newspapers had headlines and stories stating that ‘Pope’s next visit to the Gulf will be Saudi Arabia,’” Sheikh Nahyan noted.

“We believe light will prevail at the end, and by upholding good human principles of acceptance and tolerance here in the UAE, we are playing our role to help spread this light in the region.”

Your perspectives

Readers respond to gun violence. Their reactions may surprise you.

We wanted to know how readers were responding to this difficult issue, so we asked. Your answers were blunt and personal, and they displayed deep soul-searching.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Monitor Readers

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

-

Rebecca Asoulin Engagement editor

Sometimes national movements – such as pro- or anti-gun – are a powerful way to effect change. But when it comes to mass gun violence, it seems clear that Americans are also addressing the attacks on more personal and intimate terms.

Following the shooting last month at the Virginia Beach Municipal Center, in which 12 people were killed, the Monitor asked readers: Have you taken any action in your own life in response to gun violence? We got more than 100 responses. From anti-gun advocates learning how to fire weapons to gun owners locking up their guns for good, they reflect deep soul-searching – and suggest that for many, the answer lies in asserting personal control and agency against the growing impacts of mass violence.

Readers respond to gun violence. Their reactions may surprise you.

As a scourge of mass gun violence affects more and more Americans – from survivors to their families and friends to entire communities – the Monitor’s readers are digging deep for answers in response to our question: Have you taken any action in your own life in response to gun violence?

We got more than 100 responses, a number of which we’re sharing with you today. But first, some context:

From 2000 to 2017, the FBI reported 250 active-shooter incidents in the United States, resulting in 799 deaths and more than 1,400 people wounded. Among them were the 58 people killed in Las Vegas; a 2017 shooting that turned some 22,000 concertgoers into survivors. Twelve more people were killed last month at the Virginia Beach Municipal Center.

Sometimes the blur of bloodshed can make a solution seem like a lost cause. Americans, after all, remain divided over whether gun ownership and gun carry contribute to personal safety or impede a common defense.

Politics shadows the issue. After sales boomed during the Obama administration, out of concerns the government would confiscate guns, gun-makers are struggling with weak sales in the Trump era, as those fears recede.

At the same time, gun control advocacy has seen a rebound after the March for Our Lives movement started by survivors of the Parkland, Florida, school shooting last year. Even conservative states like Florida have contracted gun rights, if ever so slightly, to try to stem the violence. Conversely, many gun-owning Americans are less keen than ever to cede their personal safety to anyone else.

Sometimes national movements – such as pro- or anti-gun – are a powerful way to effect change. But when it comes to mass gun violence, it seems clear that Americans are also addressing the attacks on more personal and intimate terms.

Now to your answers. From anti-gun advocates learning how to fire weapons to gun owners locking up their guns for good, they reflect deep soul-searching. But they also suggest that the answer for many lies in asserting personal control and agency against the growing mental and physical impacts of mass violence. Responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

‘It was enough to awaken me’

“Someone I knew died at Columbine, so I responded by looking into the issue as much as I could. The more homework I did the more I transitioned from the gun-control to the gun-rights position. I’m now a member of the Liberal Gun Club.” – Nicholas Severn, via Facebook

“My brother taught me how to shoot his .22 rifle when I was a young teen. It was fun, exciting, gutsy. And I was a pretty good shot. But one day his gun exploded, sending a shard into his eye. We took him to the hospital, and before long he was well again. But I never shot a gun again. This story of violent injury is small stuff compared to what other families have suffered, but it was enough to awaken me.” – Sara Barnacle

“I joined the local San Francisco Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense after the Parkland shooting. There were so many people at the new member coffee, the organizers had to move it to a park across the street. Honestly, I’ve gone to a handful of monthly meetings and signed up for basic volunteering roles, but I’m not especially active beyond social media. I am extremely impressed with the organization and the local leadership.” – Kristin Messer, San Francisco

‘I don’t know what else I can do’

“I have a gun at home, put away, because I live in a very rural area. I would never take it out in public. I don’t know what else I can do. I have many neighbors who get all drunk and start shooting. Scary. I stay away from concerts and other public places. My grandson, who is 7, just had an active-shooter drill at school. I hate it.” – Virginia Musante, Grafton, New Hampshire

“I’m concerned about all forms of violence, and I fear that the term ‘gun violence’ often represents the fear of mass shootings. I’m an old white guy, but it distresses me to see middle-class Americans ignore the injustice and violence that plague the poor and only respond when they see victims they can identify with.” – Don Leverty, Highland Village, Texas

“I stay in more.” – Dusty Struthers, via Facebook

‘This may sound counterintuitive ...’

“Bought better locking and storage items to keep my firearms out of the wrong hands.” – Grayson Starr, via Facebook

“I was anti-gun before they became a way of life. Never let my sons have toy guns or play war or anything with the idea of gun. They are now in their 50s, and none of the four owns a gun even though they live in Indiana, Illinois, Georgia, and Florida!” – Diana Horsky Schwarze, via Facebook

“I’ve acquired more firearms in response to gun violence.” – Tony Adams, Phoenix

“I vote for anti-gun laws and pro-regulation. I know that is probably what many people will say, but honestly it’s hard not to feel powerless against this large issue. I’ve also taken time to learn how to use a gun myself and fire it. This may sound counterintuitive, but I find that the more that I understand what I’m fighting for or against, the more able I am to make rational decisions.” – Alexandra K., Los Angeles

This article is part of our “Your Monitor” initiative.

To do our work well, we need to hear from you. Share your questions and stories here.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Back to the moon

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

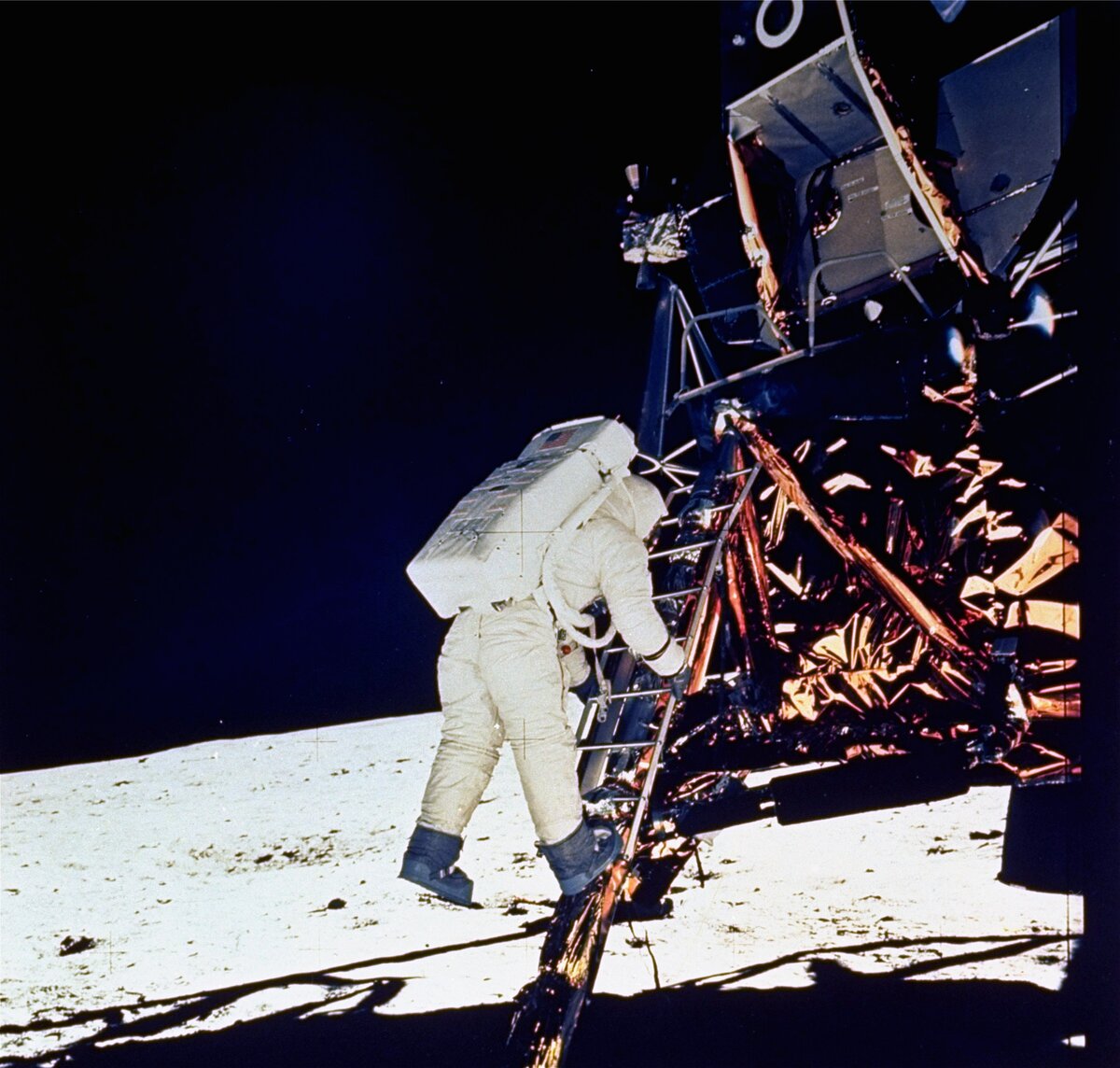

Only the United States has landed people on the moon – a dozen of them beginning with the historic Apollo 11 mission in July 1969 and ending in December 1972.

Those astronauts all were men. But that may change if NASA’s Artemis moon-landing program can stay on schedule. Artemis (in Greek mythology the twin sister of Apollo) would land a pair of astronauts, one expected to be a woman, on the lunar surface in 2024, ending a 55-year absence for humanity.

Why go back? The scientific answer is simple: There’s much more to be learned. Artemis would land near the moon’s South Pole, unexplored by humans. It’s believed to have ice deposits that could be used to supply a permanent lunar base there, which could be occupied by 2028.

All this, of course, depends on whether political and financial support for Artemis will be sustained. A budget standoff between the White House and Congress may make new funding for space exploration hard to come by.

If Artemis is to return humanity to the moon, it may take stronger political leadership to lift it off its launchpad.

Back to the moon

Over the last half-century several nations have taken potshots at the moon, landing (or in some cases crashing) payloads onto the lunar surface. But only the United States has landed people on the moon: a dozen of them in six pairs, beginning with the historic Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969, and ending in December 1972.

That only men have visited the moon remains an accurate if unfortunate statement. Though women astronauts have roamed near-Earth orbit, none have ventured to Earth’s nearest neighbor.

That may change in as little as five years if NASA’s Artemis moon-landing program can stay on schedule. Artemis (in Greek mythology the twin sister of Apollo) would land a pair of astronauts, one expected to be a woman, on the lunar surface in 2024, ending a 55-year absence for humanity.

Explaining why humans must go to the moon was an easier task for President John F. Kennedy in 1962. The Cold War between the U.S. and the then-Soviet Union was at its most frigid. Political systems were being tested: Who could best accomplish the monumental task, a democracy relying on free enterprise and free debate or a secretive, closed, top-down autocracy demanding results? The American approach won the race easily – and with it the admiration of an astonished world.

But why go back? The scientific answer is simple: There’s much more to be learned. Artemis would land near the moon’s South Pole, unexplored by humans. It’s believed to have ice deposits that could be used to supply a permanent lunar base there, which could be occupied by 2028.

All this, of course, depends on whether political and financial support for Artemis will be sustained. The Trump administration has asked Congress for an extra $1.6 billion for NASA. But if budget standoffs between the White House and Congress continue, any boost of funding for space exploration may be hard to come by.

A recent tweet from President Donald Trump further clouded the political atmosphere by stating that Mars, not the moon, was the key destination for the U.S. That seemed like a return to the position of the Obama administration, which had decided to bypass the moon and concentrate on the Red Planet.

In his famous “moon speech” of 1962, President Kennedy made a clear and urgent case for why the U.S. must go to the moon.

The attempt he said, would not be made because it would be easy, but because it would be hard and would “measure the best of our energies and skills ... ,” he told an audience in Houston. “We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people.”

If Artemis is to return humanity to the moon, it would benefit from that kind of clear vision and leadership to lift it off its launchpad.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The consciousness of Love, wherever we are

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Joan Bernard Bradley

Faced with the prospect of immigration issues while working overseas, today’s contributor found that turning to God, divine Love, lifted her fear and paved the way for a harmonious outcome.

The consciousness of Love, wherever we are

Many years ago, I taught overseas on an island. Living as an immigrant in a foreign country, I was required to renew my work permit annually. I really enjoyed the various opportunities I had there to contribute my talents and abilities and to serve unselfishly. Because my employers were happy with the work I was doing, the renewal process for the permit was straightforward and harmonious.

But one year the department of immigration denied my work permit without explanation. The school board appealed the decision, and the work permit was renewed. Unfortunately, the denial caused a delay in getting the permit stamped in my passport before I left the country for the summer. As an accommodation, the authorities issued me a travel letter that would allow me to reenter legally.

Toward the end of the summer, as I was preparing to return, I was feeling uneasy and afraid. Even though I had a travel letter, I had heard that immigration procedures on the island could get complicated if expatriate workers had not had their passports stamped for reentry before leaving the country.

Yearning to find a sense of peace, I reached out in prayer to God, divine Love, to feel His tender, loving presence and the assurance that all was well. I asked a Christian Science practitioner (someone who is engaged full time in the healing ministry of Christian Science) to help me pray about the situation. The practitioner and I discussed the 23rd Psalm, which speaks to how God cares for us as tenderly as a shepherd cares for his flock.

“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, shares a spiritual sense of this psalm. The first line reads, “[Divine love] is my shepherd; I shall not want.” I loved the idea of God, divine Love, as my Shepherd, a wise and intelligent presence governing all creation harmoniously and meeting our needs. The last verse says, “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life; and I will dwell in the house [the consciousness] of [Love] for ever” (p. 578). Because the consciousness of divine Love, the only true consciousness, includes the whole universe, each of us has the ability to feel that Love, wherever we may be.

I held fast to the idea that the consciousness of Love is all that “awaited” me. As I became more and more convinced that this spiritual fact was the reality, the fear that once dominated my thought lessened until it disappeared.

On the day of my flight, I joyfully acknowledged that the consciousness of Love was truly awaiting me. When it was my turn to have my documents processed, the officer welcomed me, and the entry procedure was harmonious. To me this was wonderful evidence that God’s love and power are indeed present to govern every moment.

This work arrangement lasted five years. I later worked for another school system and applied to the immigration department for permanent resident status, which was granted within two years. In my case, the process now felt complete, because as a resident I enjoyed work and travel freedoms that I hadn’t had before. In a sense, I felt that I was a “citizen of the world.” As Science and Health encourages, “Citizens of the world, accept the ‘glorious liberty of the children of God,’ and be free! This is your divine right” (p. 227).

Freedom to experience the consciousness of infinite Love is the divine right of each of us. These words from the “Christian Science Hymnal” give such assurance of God’s dear love for all His children:

O perfect Life, in Thy completeness held,

None can beyond Thy omnipresence stray;

Safe in Thy Love, we live and sing alway

Alleluia! Alleluia!

(No. 66, Violet Hay, ©CSBD)

Adapted from an article published in the Feb. 20, 2017, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Heads-up

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about millennials in Toronto who are pooling their money to create their own sense of home and community.