- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Cut your carbon, boost your culture

Today we look at the public response to impeachment hearings, Buttigieg and black voters in Iowa, the political stakes of the coronavirus, the importance of facts in the abortion debate, and whether a biological robot is alive.

But first, a detour to old Vienna, which is looking decidedly modern when it comes to giving its residents innovative incentives to fight climate change.

Starting next month, 1,000 users will test a new mobile app that tracks how you move through the city. If you walk, cycle, or use public transport, it will calculate how much carbon dioxide you saved by not taking a car. Once you’ve saved 20 kilos (44 pounds) of CO2, the app issues a token that can be turned in for tickets at a local history museum, a theater, a classical concert venue, or an exhibition space for art.

If the test is successful, the local government says it will roll out its cut-your-carbon-boost-your-culture app this fall.

Austria is taking several green steps. Parliament has passed a climate plan that increases speed limit enforcement on roads and aims to electrify taxis and boats. Under the new coalition of Greens and conservatives, the government plans to rely solely on renewable energy for its electricity by 2030 and to become climate neutral by 2040. To get there, it says it will start charging for carbon emissions.

Those are pretty bold steps, especially for a country that also serves as headquarters for the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Suspense-free impeachment may reverberate for years to come

The nation’s partisan divisions appear as entrenched as ever as the Trump impeachment proceedings near an end. Over the long term, the power of the presidency may have gained a significant boost.

In the short term, the impeachment of President Donald Trump by the House – followed by a Senate trial that, as of this writing, appeared to be moving inexorably toward acquittal – may do little to change minds or politics in a divided nation. The latest RealClearPolitics polling average on the question of impeachment and removal from office shows an exact stalemate, with 47.8% of Americans in favor and 47.8% opposed.

Over the long term, the new precedent set by this trial and its likely acquittal will almost certainly increase the power of the presidency, while weakening congressional oversight – changes not always perceptible to the public but consequential nonetheless.

Yet the entire impeachment episode, the most partisan so far, is “small potatoes” compared with the tectonic plates of political tribalism that put it all in motion – and are threatening American democracy, says Patrick Griffin, former legislative director to President Bill Clinton, who was impeached and acquitted 20 years ago.

“In democracy, you have to have some respect for the other side. You have to have some forbearance and some respect for other points of view, and I think we’ve lost both,” he says.

Suspense-free impeachment may reverberate for years to come

During the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump, Democratic Sen. Chris Coons of Delaware would sometimes look up to the visitors gallery from his desk in the last row of the chamber. He had offered tickets to constituents who wanted them, and hoped to see people from his nearby state in the evenings, when they could get there after work to witness this historic event in person.

But the auditorium seats in the gallery remained largely empty.

Senator Coons attributed the disinterest in the proceedings – a ratings disaster for the networks that carried them live – to two things. One was the lack of suspense. Everyone, on both sides, assumed the trial would end in acquittal.

At the same time, to many Americans “this all seems obscure, and partisan, and not relevant to their lives,” the senator said in a lengthy interview midway through the marathon days. This second factor, he added, is “more concerning” to him, because it suggests “a lack of belief in the relevance of what we’re doing.”

That assessment aptly sums up the broader impact of the impeachment of the president by the House in December, followed by the January Senate trial, which as of this writing appeared to be moving inexorably toward acquittal. On Friday night, a motion to call witnesses failed in a 51 to 49 vote, with a final vote on acquittal or conviction set for Wednesday.

In the short term, observers say it will do little to change minds or politics in a divided nation. The latest RealClearPolitics polling average on the question of impeachment and removal from office shows an exact stalemate, with 47.8% of Americans in favor and 47.8% opposed.

Over the long term, the new precedent set by this trial and its likely acquittal will almost certainly increase the power of the presidency, while weakening congressional oversight – changes not always perceptible to the public but consequential nonetheless.

Yet the entire impeachment episode, the most partisan so far, is “small potatoes” compared with the tectonic plates of political tribalism that put it all in motion – and are threatening American democracy, says Patrick Griffin, former legislative director to President Bill Clinton, who was impeached and acquitted 20 years ago.

“In democracy, you have to have some respect for the other side. You have to have some forbearance and some respect for other points of view, and I think we’ve lost both,” he says.

Democrats should never have gone down this road, he says. Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi cautioned her caucus, but “the groundswell was overwhelming.” At best, Democrats may have convinced a “small segment” of the population to abandon support for the president, but it’s too early to know that yet. “The politics of it are hit or miss.”

Led by Rep. Adam Schiff of California, Democrats have argued that President Trump tried to shake down a foreign leader for his personal benefit – asking the president of Ukraine in a July 25 phone call to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden and his son Hunter, even as he withheld nearly $400 million in U.S. military aid to the country and put off the Ukrainian president’s request for a White House visit.

The call occurred after Mr. Biden announced his candidacy for president. House Democrats began investigations last year after a whistleblower raised concerns about the phone call. But the White House refused to provide documents and barred administration officials from testifying (though some officials testified anyway).

After the House impeached the president for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, additional information has continued to emerge. The independent Government Accountability Office said it was illegal to withhold the congressionally approved aid. Leaks to The New York Times from a forthcoming book by former National Security Adviser John Bolton describe the president directly telling Mr. Bolton that the military aid to Ukraine was contingent on that government assisting with investigations into Democrats, including the Bidens. The president denied he said that.

The president’s attorneys maintained there was never a “quid pro quo” between the withheld aid and White House meeting and the request to investigate the Bidens. The president was only concerned about corruption and military burden-sharing, they maintained. They described the House impeachment process as rushed, flawed, and highly partisan. Indeed, no Republicans voted for impeachment.

The White House defense team also held that the standard for impeachment should be a crime, and argued no crime had been committed. By that logic, even if Mr. Bolton’s allegation is true – and Democrats were pressing their colleagues to call him as a witness – it would not matter because it is not an impeachable offense. (The U.S Constitution is less clear-cut than the president’s lawyers, referring to “treason, bribery, high crimes, and misdemeanors” as potential misconduct that could cause the removal of a president.)

During the Clinton trial, Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina – then one of the Republican House managers leading the charge against the president – pointed out that “reasonable people can disagree” about whether the president’s actions were impeachable or not. It was interpreted as an “out” for members of his own party and indeed, five Republicans in the GOP-controlled Senate joined Democrats to acquit the president on both charges, while five more voted to acquit on the perjury charge.

Acquittal is expected to fall much more closely along party lines this time, with a key senator such as Tennessee Republican Lamar Alexander, who has a long history of working across the aisle, calling the president’s actions “inappropriate” but not impeachable.

Considered a possible swing vote on the issue of witnesses, Senator Alexander announced late Thursday night he would not call for witnesses because there is no need for evidence “to prove something that has already been proven and that does not meet the United States Constitution’s high bar for an impeachable offense.” With the Iowa caucus coming on Monday, it’s time to “let the people decide,” he said.

Democrats vigorously disagreed, saying the president was attempting to manipulate the 2020 elections by seeking help from a foreign leader and would likely continue to do so. Failing to remove him leaves him free to act more as a monarch than a president, subject to checks and balances.

“We are witnessing the coronation of Trump, with Mitch McConnell holding the crown, and the Republicans holding his train,” said Democratic Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaii to reporters on Thursday.

Politically, acquittal will change very little, says George Edwards, a presidential scholar at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas. The public will see the whole process as “politics as usual.” Gridlock in a divided Washington will continue. Democrats will continue to pass legislation in the House that goes nowhere in the Senate, while Senate Republicans focus mainly on confirming judges.

In a broader sense, the arguments made by the president’s team “provide a basis for much less restriction on presidential power,” he says, adding that the administration’s refusal to cooperate with documents and witnesses “really has weakened congressional oversight.”

Mr. Griffin, however, says it’s not a given that this will translate into future abuses. That will depend on the people elected and the circumstances of the moment.

“The balance of power has shifted dramatically to the president for the moment,” he says. “But this is a dynamic that goes back and forth, and whether it’s irreversible, I’m not sure. That depends on the next president, and the next president after that.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated at 6:15 p.m. with the results of the Senate vote.

Why the black mayor of this Iowa city endorsed Buttigieg

To take a closer look at two common arguments – that Pete Buttigieg has been unable to win over black voters and that Iowa is too white to host the first nominating contest in the U.S. – our reporter went to the diverse community of Waterloo.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

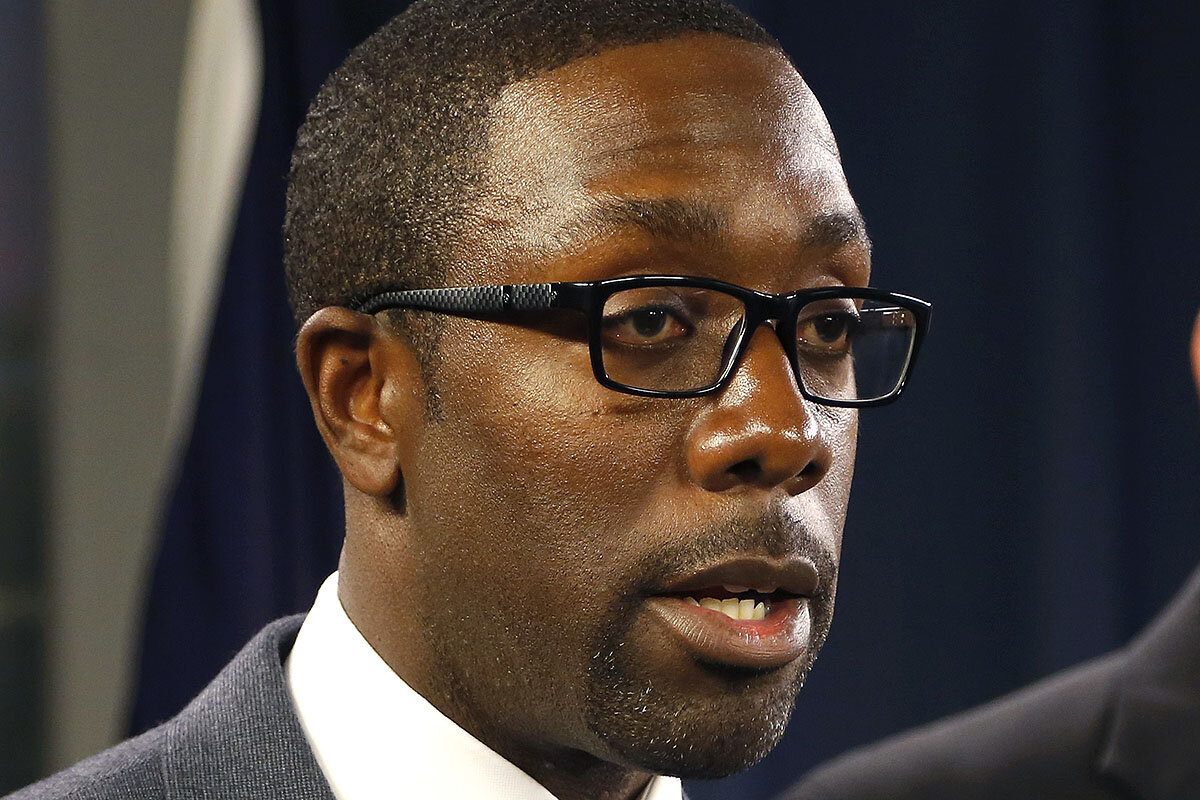

They met at an Accelerator for America event in 2018 – two mayors of midsize Midwestern cities that struggled with industrial decline and racial tension. Last summer, after then-Mayor Pete Buttigieg launched his presidential campaign, Mayor Quentin Hart welcomed him to Waterloo and brought him to the Fourth Street bridge over the Cedar River for the first of several visits. In January, he endorsed him.

Mayor Hart’s Jan. 14 endorsement may have surprised pundits, who routinely describe Mr. Buttigieg as unable to win over black voters. It also runs counter to criticism from the African American community in South Bend, Indiana, where Mr. Buttigieg just concluded two terms as mayor.

“My role is not to debunk anything Pete’s city feels about him or his leadership,” Mayor Hart says in a phone interview. “My role is to tell what I know about Pete from my relationship with him.”

It is by no means a guarantee that the rest of Waterloo’s black community will follow. There is a wide range of views among African Americans here, who are expecting a sharp uptick in black turnout, even as Iowa itself has been hammered for being “too white” to host the first-in-the-nation caucus.

“It hurts to hear that,” says the Rev. Frantz Whitfield, pastor of the Mount Carmel Missionary Baptist Church. “I love my state, I love Iowa. ... There’s so much diversity here, which I don’t think the media picks up on.”

Why the black mayor of this Iowa city endorsed Buttigieg

Mayor Quentin Hart, an African American whose Iowa metro area was ranked No. 1 in America for racial disparity by one source in 2018, recently endorsed Pete Buttigieg as the presidential candidate best suited to help communities like his.

“Pete has probably one of the most aggressive plans for black America,” says Mayor Hart of Waterloo, Iowa. Plus, he adds, he’d like to see someone in the White House who has the accountability of a local leader who runs into his or her constituents in the grocery store or local Walmart. “I believe we need a mayor’s approach.”

The Jan. 14 endorsement may have surprised national pundits, who routinely describe Mr. Buttigieg as unable to win over black voters. It also runs counter to criticism from the African American community in South Bend, Indiana, where Mr. Buttigieg just concluded two terms as mayor.

If Mayor Hart’s backing is a boon for Mr. Buttigieg, however, it is by no means a guarantee that the rest of Waterloo’s black community will follow.

Amid increased engagement from African Americans, who make up 17% of the population here, Sen. Elizabeth Warren drew 300 people to a house party; former Vice President Joe Biden won the vote of an influential pastor; and Sen. Cory Booker, who became the first presidential candidate to open a campaign office in Waterloo's black community, gained traction before dropping out.

Though Mr. Buttigieg has gained high-profile supporters and drew 600 to an outdoor rally in September - on a rainy day, no less - some here don’t like what they’ve heard about his track record on racial issues back home.

Mayor Hart, whose long-time friends and associates describe him as a very deliberate decision-maker, acknowledges the criticism from South Bend – but has a different perspective as a fellow mayor. In an Op-Ed announcing his endorsement, he pointed to statistics like black unemployment dropping by 70% during Mr. Buttigieg’s tenure.

“My role is not to debunk anything Pete’s city feels about him or his leadership,” he says in a phone interview. “My role is to tell what I know about Pete from my relationship with him.”

The mayor

They met at an Accelerator for America event in 2018 – two mayors of midsize Midwestern cities that had struggled with industrial decline and racial tension.

Last summer, after then-Mayor Buttigieg launched his presidential campaign, Mayor Hart welcomed him to Waterloo and brought his visitor to the Fourth Street bridge over the Cedar River.

To the west was Waterloo’s largely white community, with its cluster of hotels and fast-food chains. On the other bank stood the struggling East Side, where African Americans were sequestered when they came to break a railroad strike in the early 1900s. Parts of the East Side burned in a riot in 1968, in which long-simmering tensions around racial inequality broke out after police tried to arrest a man at a high school football game.

Quentin Hart was standing here when he got the phone call in 2015 confirming that he would become the city’s first African American mayor. He vowed to work to bridge the divides in his community.

Within three years, Waterloo was named Iowa’s small business community of the year and one of the top 10 job markets in the country. Crime had dropped to the lowest level in decades, though residents still express concern about nighttime gun shots ringing out across their neighborhoods.

There was also bad news in 2018, however: The online website 24/7 Wall Street, using U.S. census data, concluded that Waterloo, when paired with neighboring Cedar Falls, had the largest “social and economic disparities along racial lines” of any U.S. metro area.

It found that African Americans were five times more likely to be unemployed than their white neighbors, and those employed earned only about half the median income of their white counterparts. And the rate of homeownership was just 32%, compared with 73% among white residents. Though Waterloo fared slightly better in the index’s 2019 rankings, coming in at No. 3, the racial disparities are still stark.

Which is where Mr. Buttigieg’s plan comes in, promising to address systemic racism and “unlock the collective potential of black America.”

The Douglass Plan, named after abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass, is similar in scope to the Marshall Plan that funded European reconstruction after World War II. It includes everything from reforming the criminal justice system to improving access to mortgages.

“What got my attention was he was addressing it not with a Band-Aid approach of, ‘Let’s just throw a program out there,’” says former state Rep. Deborah Berry, who was invited to a Buttigieg roundtable with local black leadership in December.

The political newcomer

Bridget Saffold may not be recognized as a leader per se, but if black turnout is up on caucus night, she will have had a lot to do with it.

A nurse and mother of four who is finishing up her bachelor’s degree in nursing, she’s never been very involved in politics. But that changed with President Donald Trump’s election. In the past year, she has found time to host events – including the first-ever house party in her community, with Elizabeth Warren. Some 300 people filled her backyard.

She has been intentional about inviting people who might not otherwise get involved.

“I want to say ‘little people,’” she says over a 99-cent breaded tenderloin sandwich special at the local Steamboat Gardens restaurant. “Just regular working people who don’t get heard.”

When they came out, “It was the first time they were hearing, ‘Hey, it’s important for you to be part of the process. You matter,’” says Ms. Saffold.

One of the concerns about Mr. Buttigieg is that even if he manages to win the Democratic nomination, he won’t be able to get out the black vote in the general election next fall, and Democrats will lose.

“The narrative in the media is that if he fails, it’s because he didn’t connect with black voters,” says Ryan Stevenson, an organizer for the Booker campaign who grew up in Waterloo. “Don’t just put the blame on us.”

There are other groups Buttigieg doesn’t connect well with either, such as younger white voters, he says. Plus, he adds, the lack of connection is a two-way street.

That said, Mr. Stevenson takes issue with some of the criticism Mr. Buttigieg has faced, including a New York Times article this week about tensions within his campaign over the treatment of minority staffers.

“It’s an issue that all campaigns are facing, so for [the Times] to frame it just as a Buttigieg issue is not right,” says Mr. Stevenson.

Plus, such criticisms may be overblown. An online survey this fall found Mr. Buttigieg polling the highest of any candidate among non-white voters. Also, 46% of his senior advisors are people of color. Angela Weekley, manager of community inclusion at Veridian Credit Union in Waterloo, says of the people he’s surrounded himself with: “That’s the type of America I’d like to see.”

The pastor

Iowa itself has been hammered for being “too white” to host the first-in-the-nation caucus.

“It hurts to hear that,” says the Rev. Frantz Whitfield, pastor of the Mount Carmel Missionary Baptist Church in Waterloo. “I love my state, I love Iowa, even as an African American man. ... There’s so much diversity here, which I don’t think the media picks up on.”

But the Democratic candidates have picked up on those growing pockets of minorities, at least more than in prior years.

“A lot of them are in Waterloo quite often,” Mr. Whitfield says – 80 times, to be precise. “It makes people feel good.” The front-runners have each visited Waterloo four times with the exception of Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who has made seven trips. Most of them are returning this weekend for a final swing.

The pastor, who endorsed Mr. Biden in July, estimates that 95% of the people he speaks with, from the gas station to those in his own pews, have said they’re also going with Biden.

One of them might be Anna Weems, a 92-year-old civil rights activist who brought the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. here in 1959. But when asked who she thinks would best be able to advocate for Waterloo from the White House, she guffaws.

“It’s not the White House, it’s what we can do,” she says, recalling King’s preaching of unity. “It’s brothers and sisters that touch each other every day.”

Coronavirus outbreak highlights cracks in Beijing’s control

China has mobilized to forcefully fight the coronavirus outbreak. But the crisis has highlighted cracks in its rigid governance – and raised key questions about its top-down system that could linger long afterward.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When Chinese officials are confronted with a problem, says Professor Minxin Pei, they decide which type of challenge it is: technical or political.

“If it’s political,” he says, “I would think first about how it will reflect upon me, then I just kick the ball upstairs. I just keep kicking it upstairs, and wait for decision-making.”

And the top of the stairs, of course, is China’s leader Xi Jinping – the country’s most powerful in decades.

It’s that slow, centralized decision-making, some China observers argue, that has slowed down the country’s response to the coronavirus outbreak, which now logs over 10,000 cases. That, and a system that allows little room for criticism or transparency, with little national media mention of the outbreak until several weeks in.

But cracks have appeared amid the crisis. With the cat out of the bag, anger is rampant. The situation raises fundamental questions about China’s government, as Mr. Xi faces his widest domestic challenge.

“Real restraints on hard news and investigative reporting, when combined with [a] push for positivity, are a toxic combination,” writes David Bandurski, co-director of the China Media Project. “They risk creating a society that has essentially no immune system.”

Coronavirus outbreak highlights cracks in Beijing’s control

A man in Wuhan, clutching a mask across his face, described his emotions from inside the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak. He posted the video to YouTube.

China’s leadership has escaped to an island, he claimed, his face reddening with anger, while ordinary Chinese were left trapped. “We have no power,” he said, begging the public to spread the word. “I want to create some public pressure so the Chinese government doesn’t escape their responsibilities.”

In Shanghai, an infectious-disease doctor proclaimed he’d switch out his front-line doctors with Communist Party officials. “Didn’t they all pledge an oath when they joined the party?” he asked, his sarcasm apparent despite his level voice.

In a political and social environment that typically allows little room for criticism of Chinese leadership, cracks have begun to appear in Beijing’s control of its populace. The coronavirus outbreak, now logging over 10,000 cases, with more than 200 deaths and an infection spreading worldwide, raises fundamental questions about China’s style of government.

Will “2019-nCoV” be the thing that most tests the limits of Beijing’s authoritarian, centralized style of governance? Would greater transparency in the early days of the virus, back when only a few dozen were sick in an interior Chinese city, have prevented a global spread? Is this the first big political test for Xi Jinping – China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong?

A “golden window,” gone

In Wuhan, a city of 11 million in Hubei province, the first patients showed symptoms of a mysterious new virus in early December, linked to a wholesale market selling seafood along with wild animals.

Thus began what Minxin Pei calls the critical period.

“Mid-December through mid-January,” says Dr. Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, California. “They lost the golden window – that’s roughly a month when they could have issued a general alert. At least, people would have been screened, they wouldn’t be going places.”

The first evidence the central government was aware of the situation came on Dec. 31, when Beijing dispatched a team of medical experts to Wuhan. From there, the situation progressed rapidly. On the first day of 2020, authorities interrogated eight Wuhan doctors and accused them of “rumormongering” for simply posting about the virus. Another few weeks of inaction passed until Jan. 20, when the number of cases seemingly doubled overnight. Finally, the central government sprang to action.

The system’s opacity may have prevented a rapid early response, explains Professor Pei, an expert on Chinese governance. When Chinese government officials are confronted with a problem, “they usually perform what I call triage, dividing the issue into technical or political.”

A technical problem they might handle on their own. “If it’s political,” Professor Pei says, “I would think first about how it will reflect upon me, then I just kick the ball upstairs. I just keep kicking it upstairs, and wait for decision-making.”

At the top of the stairs, of course, is Mr. Xi, who has further consolidated Beijing’s power.

Therein lies the problem, says Professor Pei. “Decision-making is a lot slower when there’s excessive centralization.”

Missing headlines

Meanwhile, an analysis from the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong shows state-owned papers made little mention of the virus in the first 20 days of January. In the lead-up to the Chinese New Year – the largest annual migration of people in the world – the papers trumpeted reports of the party’s success in eradicating poverty, convening top leaders in a show of solidarity, and strengthening Mr. Xi’s connection with the people.

On Jan. 23, the world learned of Beijing’s order to quarantine Wuhan. But inside China, the papers were still relatively mum; only two days later did two reports appear on the right-hand side of the People’s Daily’s front page, hardly reflective of the panic developing on the ground at that point, with more than 2,000 sick in China and 40 infected overseas.

Today, with the cat out of the bag, anger is rampant.

“Everyone’s on WeChat, everyone’s on Weibo, and the amount of messages going back and forth is in the billions,” says Elanah Uretsky, an anthropologist of China at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. “It’s spreading panic, and it isn’t serving anyone well.”

Ultimately, in her estimation, Beijing simply wasn’t prepared to handle an outbreak of this size. Though decision-making has been centralized, the health care system is still largely local or provincial, Professor Uretsky says.

When the SARS epidemic emerged in November 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) wasn’t informed or fully involved for three months, until about 300 people had already died.

David Bandurski, co-director of the China Media Project, says there’s been no real transformation in the way China handles major crises since then – and he’s not surprised.

“Real restraints on hard news and investigative reporting, when combined with [a] push for positivity, are a toxic combination,” Mr. Bandurski writes in an email. “They risk creating a society that has essentially no immune system.”

“War” mode

Yet the power of the Chinese state has now been brought to bear. The central government announced that new multistory hospitals would be built in a matter of days. More than a thousand doctors have been dispatched to Wuhan, according to Professor Pei, and the production of masks has certainly been cranked up. “This is what I call the militarization of government,” he says. “They treat such a task as war.”

In a country of 1.4 billion people, the government has also managed to quarantine entire cities totaling around 50 million people – with no rioting.

“With SARS, the same thing happened,” says Brandeis’ Professor Uretsky. “As soon as they’ve acknowledged the problem, they’re solving the problem, despite all the justified criticisms of that style of governance.” Wuhan also has a BSL-4 laboratory, the highest possible rating for handling dangerous agents.

WHO has now declared coronavirus a public health emergency, the United States has given its diplomats in China a choice to leave, and many airlines are halting flights. On Thursday, the U.S. State Department warned Americans against traveling to China.

The Chinese economy is bound to take a hit, as will countries whose economies are closely intertwined with China’s. During SARS, China’s economy was just a whisper of the global behemoth it is now.

Which brings up the question: What does this all mean for Mr. Xi?

The Hong Kong protests don’t register for most mainland Chinese, meaning the coronavirus is really the first significant domestic challenge to Mr. Xi’s authority. Indeed, with all provinces showing disease outbreak, no one is untouched by the crisis.

For years, China watchers had posited any number of events as “the event” that might shift China’s political thinking, says Jeremy Wallace, a China expert at Cornell University – including SARS, the global financial crisis, and the Bo Xilai political scandal.

In communist regimes, “turning points are few,” argues Professor Pei. “But – this could be part of a constant erosion.”

Back in Wuhan, the young man in the mask concludes his 10-minute video imploring the world to care about ordinary people like him. He asks for “international pressure and awareness.”

“We have high housing costs, living costs, inflation,” he says. “We, too, want to live with democracy and freedom ... but we can’t. We are helpless.”

The Redirect

Why facts matter on both sides of the abortion debate

Abortion is deeply tangled up in politics, personal beliefs, and individual experience. The key is to have every conversation grounded in facts.

When Americans talk about abortion, they often do so in terms of binaries: “pro-life” versus “pro-choice,” “anti-life” versus “anti-choice.” It’s a framework that divides the public, elevates the most extreme voices, and creates an environment in which people are primed to believe only the side with which they agree.

Such a climate becomes a breeding ground for misinformation. For example, although the partisan gap in views around legal abortion has widened in recent years, surveys over the past four decades show that most Americans’ opinions fall somewhere in the middle of the debate.

Despite all the fervor around the issue, the most recent studies have found that the number and rate of abortions are lower than at any time since 1973, when the Supreme Court’s ruling on Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure nationwide. Data show that it’s not because there are more laws restricting abortion – a growing reality in many states. In fact, abortion rates are higher in countries where the practice is illegal.

And despite growing concern that abortions are becoming more common in the final weeks of a pregnancy, all but 1.3% occur before the 21st week. – Jessica Mendoza, multimedia reporter

The Redirect: Why facts matter on both sides of abortion debate

Behold the xenobots – part frog, part robot. But are they alive?

What does it mean to be alive? A new class of robots, built from frog stem cells, is testing the boundaries of how we define life – and how we should treat it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

They’re being called the world’s first “living robots.” But what, exactly, does that mean?

Designed by a supercomputer, xenobots can move toward a target, form a group to push pellets to a central location, and self-repair. But they’re made entirely from frog stem cells.

But for now, these biological blobs are little more than a proof of concept. These xenobots are simple prototypes. But future iterations could, conceivably, be used for environmental clean-ups or delicate medical procedures.

Still, the existence of any biobots raises ethical questions. The answers could have widespread implications. How we choose to define and categorize these creations could inform how we relate to them: Are they biological organisms? Technological machines? Or both?

“The terms that we use to describe them can be really important, because they make us think along certain lines,” says Simon Coghlan, an ethicist at the University of Melbourne, and a veterinarian, who was not involved in the project. “We have all these impressions and ideas and associations that are linked with robots, which are different from the kind of associations and responses that we have to living organisms.”

Behold the xenobots – part frog, part robot. But are they alive?

At first, they are just blurry blobs. But when Douglas Blackiston turns a knob on the microscope, they suddenly come to life in sharp relief.

They look like miniature, lumpy matzo balls suspended in water, but they move as if swimming with intention.

These are no ordinary lifeforms. Rather, Dr. Blackiston built them using frog stem cells and the guidance of artificial intelligence. They are the first “living robots.”

At least that’s how Dr. Blackiston of Tufts University and his colleagues at Tufts and the University of Vermont (UVM) describe them. But these “xenobots” – a nod to the Xenopus laevis, or African clawed frog – don’t fit neatly among nature’s creatures or traditional robots.

The team built these millimeter-wide biobots to move toward a target, form a group to push pellets to a central location, and self-repair, according to a paper published earlier this month. Future iterations could, conceivably, be used to clean microplastics from waterways or to deliver medications to precise locations in the body. But for now, these biological blobs are little more than a proof of concept.

Still, as prototypes for what might later be possible, the existence of xenobots raises ethical questions. The answers could have widespread implications. How we choose to define and categorize these creations could inform how we relate to them: Are they biological organisms? Technological machines? Or both?

“The terms that we use to describe them can be really important, because they make us think along certain lines,” says Simon Coghlan, an ethicist at the University of Melbourne in Australia, and a veterinarian, who was not involved in the paper. “We have all these impressions and ideas and associations that are linked with robots, which are different from the kind of associations and responses that we have to living organisms.”

How to build a biobot

Perhaps the best way to start to figure out what to call a xenobot is to understand how it came to be.

Before being assembled in a petri dish, xenobots were formed on a supercomputer. UVM researchers tasked a machine learning program with testing out various body configurations. Dr. Blackiston at Tufts then recreated the virtual bots that exhibited desired behaviors in their lab.

He began by extracting stem cells from frog embryos. When clumped together, those cells naturally ball up. Then, using microsurgical tools, he would shape them into the AI-selected shapes.

Biobots are not made of metal or plastic like common machines. But if you define a machine as something that is designed to perform a specific task, says Michael Levin, director of the Allen Discovery Center at Tufts and a senior author on the paper, the xenobots measure up.

But, more importantly for ethical questions, are they alive?

“We think we know what a robot is. We think we know what a living thing is. But for all these things in biology, there are all these in-between cases,” Dr. Levin says. “What this project really pushes the field to do is to think about better definitions for all these terms.”

It’s easy to say whether most things we see are alive or not. Everyone would look at a fox or a tree, for example, and agree that it’s living. But determining a precise definition of what it means to be alive is a bit fuzzier. And if something is considered to be living, is it necessarily an organism?

“In this case, with the xenobots, the curious thing is that they are a bunch of frog cells stitched together,” says Dr. Coghlan. “You could say those individual cells are living – they’re frog cells, we’d categorize them as life, in a sense – but they’re stitched together to form these new kinds of small, one-millimeter-sized bodies.”

They behave in some ways biologists would use to describe an organism – they can move around and perform certain actions – but are lacking some other characteristics often cited. They also have not shown the ability to reproduce, or to find food in their environment or make energy to sustain themselves in any other way.

Something can be considered an organism and not receive much moral consideration from humans, however. The welfare of plants or bacteria, for example, doesn’t typically get much attention. But animals usually do.

The xenobot experiment was reviewed by an ethics committee, Dr. Levin says, as any research using frog embryos would be. “They ask questions like, what kind of experience is this creature likely to be capable of, and what are you doing to it, and is it worth the benefits to society for whatever that is?”

What a life-form is likely to experience may be key to the moral question, says Dr. Coghlan. Although these xenobots are fairly simple and lack nervous systems, if future programs “could perhaps develop new kinds of organisms that are capable of feeling, or pain, or suffering, then I think that would raise more serious ethical questions.”

Hubris and unintended consequences?

The human creation of a life-form also presents a broader concern for some that scientists are perhaps being too hubristic in trying to control biology.

Creating something new from something that already exists in biology isn’t a radical concept, Dr. Coghlan points out. Humans have been domesticating animals, creating hybrids (like a mule), and selectively breeding crops for centuries. But, he says, that concern about hubris might “point to some deeper ethical or moral response to the ways in which we have this kind of power over nature.”

Those concerns extend beyond the welfare of biobots themselves to worries about the unintended, cascading consequences of altering something in nature.

“Living organisms evolve and change, and oftentimes evolve and change in ways that we don’t expect, particularly once you actually release them into the environment and they interact with other living things,” says Nita Farahany, who studies the ethical, legal, and social implications of emerging technologies at Duke University. “The implication could be quite problematic.”

Science fiction films have played out such scenarios to terrifying ends. Think about the often-quoted line from “Jurassic Park”: “life finds a way.” What if the xenobots found a way to reproduce in the wild, or bred with other organisms? Or what if their behavior could alter in a nonlaboratory environment, to detrimental effects?

The researchers are in no rush to let the xenobots out of the lab. “Let’s be super clear, okay? We’re not about to dump these in the waterways,” Dr. Levin says. “Let’s just not have any misunderstanding there.”

Rather, he and Dr. Blackiston see their biobots as a “testbed” for ethical quandaries. They’re eager to use the xenobots to study cellular function in the laboratory as a way of better understanding what consequences occur when humans manipulate nature, and how best to harness such technologies.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why nurses are in the spotlight in China

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a major health crisis like the virus outbreak in China, one of the first casualties can be the public’s trust in government. As more Chinese criticize the Communist Party’s response, officials have revved up a propaganda campaign to highlight those frontline workers who – as in most countries – are widely trusted: nurses.

The official Chinese press depicts nurses coping with the outbreak as courageous or tirelessly compassionate. While such tales may help cover over the ruling party’s failings, nurses are indeed special. This is especially so during disease outbreaks when supportive care is critical for a patient’s recovery. Besides their technical knowledge, nurses provide kindness and attention, which can facilitate healing.

As global disasters increase – whether from climate change or epidemics – nurses are in short supply. But the trust in them is not. The latest Gallup Poll in the United States shows why. Of all professions, nurses rate the highest in honesty and ethics at 85%.

The Chinese government is learning a lesson about the character traits needed to earn the people’s trust. It has sent more than 6,000 health workers to the center of the virus outbreak. Their work is worth highlighting.

Why nurses are in the spotlight in China

In a major health crisis like the virus outbreak in China, one of the first casualties can be the public’s trust in government. Leaders in Beijing are now very aware of this. Many Chinese have become fearless in criticizing the Communist Party’s response. As a result, officials have revved up a propaganda campaign to highlight those frontline workers who – as in most countries – are widely trusted: nurses.

The official Chinese press depicts nurses coping with the outbreak as courageous. “My colleagues and I are not afraid of being infected,” one nurse is quoted as saying. Or the press shows the tireless compassion of health workers. “From the expression in the nurses’ eyes, I felt their exhaustion and knew the job must be more tiring than I had expected,” one nurse reportedly said of the others. During China’s last major virus outbreak in 2002-03, the propaganda was quite explicit in commanding people to “love your nurse.”

While such tales may help cover over the ruling party’s failings, nurses are indeed special in their professional qualities. This is especially so during outbreaks of infectious diseases when supportive care is critical for a patient’s recovery. Nurses are also the largest part of the health workforce in every country.

Beyond their technical knowledge, nurses are widely seen as inherently selfless. They provide kindness and attention, which can facilitate healing. Many aim to fulfill their profession’s so-called Nightingale pledge, which calls on each nurse to “devote myself to the welfare of those committed to my care.” Florence Nightingale, the 19th -century nursing pioneer, wanted nurses to focus more on the well-being of patients than the sickness. “Apprehension, uncertainty, waiting, expectation, fear of surprise, do a patient more harm than any exertion,” she advised.

As global disasters increase – whether from climate change or epidemics – nurses are in short supply. But the trust in them is not. The latest Gallup Poll in the United States shows why. Of all professions, nurses rate the highest in honesty and ethics at 85%. That level of trust has been consistent over 18 years of polling even as trust in other professions has declined. It also is much higher than trust in doctors, clergy, and police.

The Chinese government is learning a lesson about the character traits needed to earn the people’s trust. It has sent more than 6,000 health workers, mainly nurses, into Hubei province, the center of the virus outbreak. Their work is worth highlighting. Rather than set up a digital surveillance system to track the trustworthiness of their people, Chinese leaders themselves can try to be more trustworthy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Unity

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By David C. Kennedy

Even when we don’t see eye to eye, there’s a divine basis for feeling and expressing “a softened look, a kinder thought” toward one another, as this poem highlights.

Unity

If the two of us do not see eye to eye,

then let us meet in the encircling glow

of what we truly see – a sister, a brother,

a child of our Father-Mother.

To embrace this loving light

brings a gentleness to our common tie,

a softened look, a kinder thought,

a heart won over, as Christ draws back the veil

and repentant eyes now glimpse

the perfect likeness always there –

a cherished gleam of God’s own countenance.

With one Father, even God, the whole family of man would be brethren; and with one Mind and that God, or good, the brotherhood of man would consist of Love and Truth, and have unity of Principle and spiritual power which constitute divine Science.

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” pp. 469-470

Poem originally published in the Sept. 2001 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

Tour guide on a mission

A look ahead

That’s a wrap for today. Join us Monday when editor Mark Sappenfield talks with Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn about their new book about working-class America, “Tightrope.”