- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Can Democrats win back Trump voters? Dubuque, Iowa, may offer clue.

- In Trump plan, Arab Israelis see assault on their identity

- Beyond the picket fence: How one city creates affordable housing

- Price of Rwanda’s clean streets? Detained children, NGO says.

- What makes a strong America? Strong Americans.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How to reframe a debate? Focus on the heart.

Welcome back. Today we look at engagement in Iowa, identity in Israel, responsiveness in Minneapolis, order and disorder in Rwanda, and hope that’s both local and national. But first, it’s a good moment to think about how we push for the political outcomes we want.

One partisan process, the Senate impeachment trial, wraps up. Today intraparty challengers get real in Iowa. The points of contention are familiar: health care, wages, climate, more.

Never mind the politicians. Can individuals better frame these debates? Can we assert facts without judgment?

On a biggie – climate change – Katharine Hayhoe has “found a strategy that works,” reports Harvard Business Review: “focusing on the heart – that is, what we collectively value – as opposed to the head.”

Dr. Hayhoe, a climate scientist we’ve interviewed in the past, prescribes this tack: “Don’t start with fear, judgment, condemnation, or guilt. ... [S]tart by connecting the dots to what is already important to both [sides], and then offer positive, beneficial, and practical solutions that we can engage in.”

That tends to run against party lines – even against how some say humans are wired.

“Motivated reasoning,” notes the journalism-trend watcher Nieman Lab, “is what social scientists call the process of deciding what evidence to accept based on the conclusion one prefers.”

Dismissing the views of the “other” is easy. Not dismissing them can mean sacrificing a dearly held identity. “This is not just a problem for conservatives,” Nieman notes. “[L]iberals are less likely to accept expert consensus on the possibility of safe storage of nuclear waste or on the effects of concealed-carry gun laws.”

Respect is essential. What Dr. Hayhoe says about her issue – even as some deny its existence – matters broadly. “As humans, we want to be part of a solution,” she says. “That is part of what gives us hope ... the idea that we’re actually doing something good for the world.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Can Democrats win back Trump voters? Dubuque, Iowa, may offer clue.

We’ve all heard about the supposed animosity between reporters and mainstream Americans. But Monitor writers in Iowa said they experienced a deep reward of their work there: meeting people willing to engage with them.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

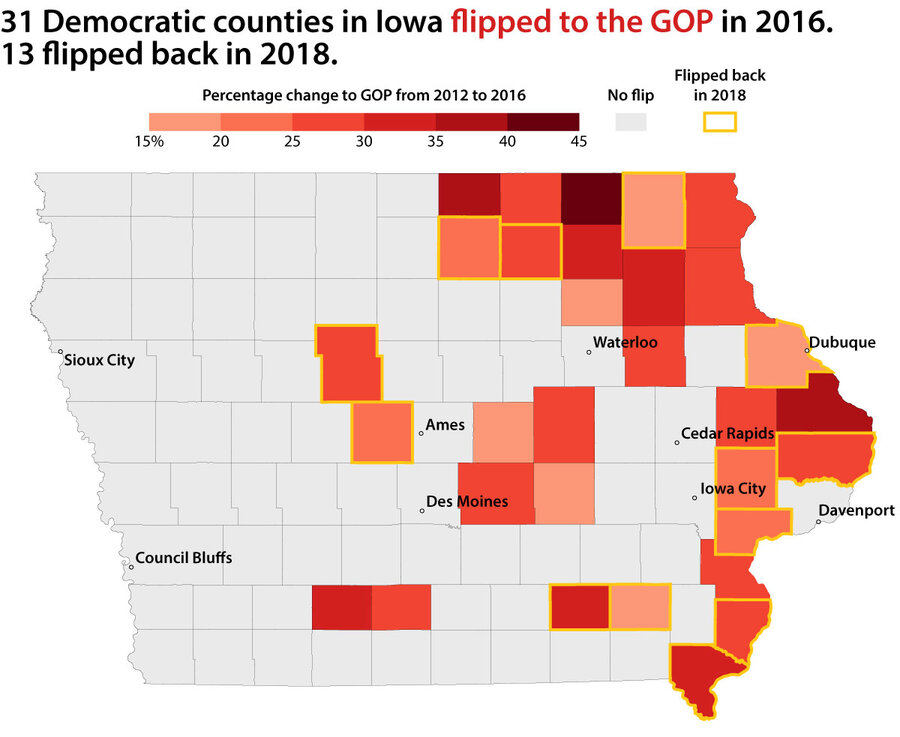

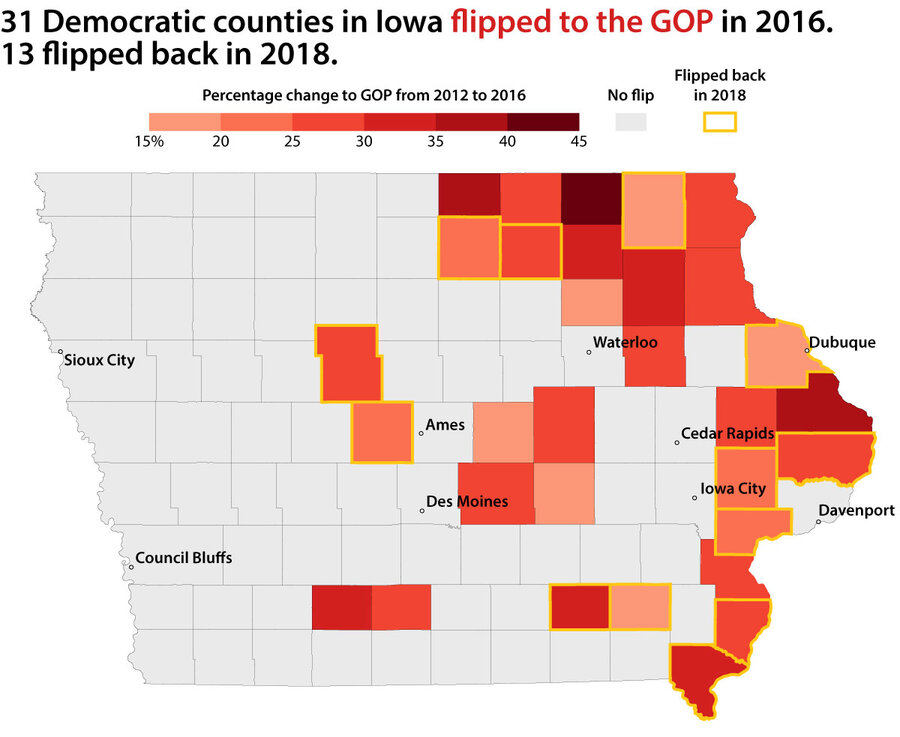

After twice voting for Barack Obama, Iowa was one of six states that flipped to Donald Trump in 2016. Some Democratic strategists have lately suggested the party shouldn’t bother competing for its six electoral votes this November – viewing its rural, graying profile as a harder lift than, say, Sun Belt states with booming young and immigrant populations.

Yet all the focus on “Obama-Trump voters,” and whether Democrats have lost them for good, tends to overlook other factors – including the lower turnout in 2016. While Mr. Trump got 7% more votes in Iowa than Mitt Romney in 2012, Hillary Clinton underperformed Mr. Obama’s vote tally by 22%.

In Dubuque, the most populous county in northeastern Iowa that voted for Mr. Trump, more than five dozen interviews with residents suggest – for now – a resurgent support for Democrats. At the very least, Dubuque offers a key test for Democratic candidates, since electoral success here could portend similar results in critical swing states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, where white working-class voters may make the difference.

“The story over and over in Iowa with Democrats losing is, we fail in the rural areas,” says Nathan Thompson, the Democratic chair in nearby Winneshiek County. “The Warren and Buttigieg campaigns have made a real effort to … hit some of those rural doors.”

Can Democrats win back Trump voters? Dubuque, Iowa, may offer clue.

Cathy Mauk Dickens has lived in Iowa for more than four decades – but until last year she never really knew what a caucus was.

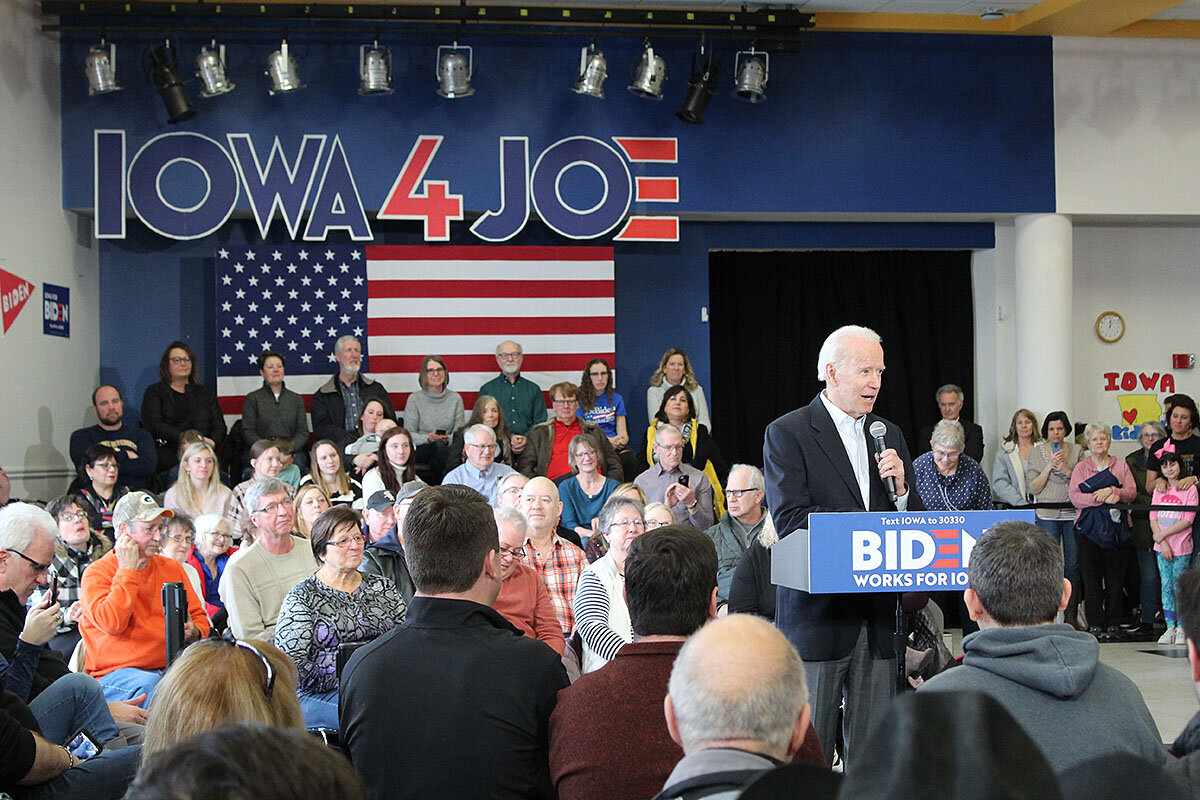

Now, she’s a precinct captain for former Vice President Joe Biden, preparing to participate for the first time in an election event she and other volunteers milling about the campaign field office see as crucial for American democracy.

Standing by a table of pizza and potluck dishes that have cooled off since Jill Biden arrived to address the crowd, Mrs. Dickens explains that she feels partially responsible for what happened in 2016.

It was she who took her sister to a Trump rally as candidates made the rounds through Iowa, host of the first-in-the-nation caucuses. Her sister became a devout follower – and still is, praising the president for his patriotism, support for the military and law enforcement, stance against illegal immigration, and role in creating the lowest unemployment in decades.

It’s not until 15 minutes into the conversation that Mrs. Dickens quietly reveals that she, too, voted for Donald Trump after having twice supported Barack Obama – thinking a businessman could boost the economy.

“He hadn’t shown his colors yet,” she says. “Right away, when I saw the lying … I felt so bad.”

Thanks in part to voters like Mrs. Dickens and her sister, Dubuque County followed the rest of eastern Iowa in 2016 and swung red for President Trump after years of reliably voting Democratic. Iowa as a whole also went for Mr. Trump, after twice awarding its electoral votes to President Obama.

Some Democratic strategists have lately suggested the party shouldn’t bother competing for Iowa’s six electoral votes in November – viewing its rural, graying profile as a harder lift than Sun Belt states with their booming young and immigrant populations.

Yet all the focus on “Obama-Trump voters,” and whether Democrats have lost them for good, tends to overshadow other key factors behind Iowa’s flip to the GOP – including far lower turnout in 2016. While Mr. Trump got 7% more votes than Mitt Romney in 2012, the bigger storyline for Democrats was that Hillary Clinton underperformed Mr. Obama’s vote tally by 22%.

In other words, what appeared on blue- and red-checkered maps of Iowa as a dramatic shift toward Republican values may have been more based on personality than principle – including dislike of Mrs. Clinton and the novelty of an anti-establishment candidate who wasn’t afraid to call it as he saw it.

“Hillary was within walking distance of my house in 2016, and I didn’t even bother going to see her,” says Ed Gansemer, a lifelong Dubuquer and Democratic voter. Although Mr. Gansemer, a retired electrician at the local John Deere plant, voted for Mrs. Clinton in the end, others couldn’t overcome their antipathy, casting their ballots for a third-party candidate or staying home altogether.

More than five dozen interviews with residents here, conducted everywhere from Target to town halls, suggest – for now – a resurgent support for Democrats in Dubuque, the most populous county in northeastern Iowa that voted for Mr. Trump in 2016 and then for a young Democratic congresswoman in 2018. At the very least, Dubuque offers a key test for Democratic candidates – since electoral success here could portend similar results in critical swing states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, where white working-class voters may make the difference.

While many Democrats here express distaste for Mr. Trump, they also raise questions about whether a candidate as liberal as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren could win come November.

“We’re afraid if Sanders gets it,” says Linda, a middle-aged woman who declined to give her last name, at a Joe Biden town hall at Clarke University in Dubuque the day before the caucuses.

“Republicans who I know who don’t like Trump any more – they wouldn’t vote for a socialist,” agrees her friend Mary.

Wayne Demmer, a farmer who raises cattle, hogs, and grain outside Dubuque, is nearly certain the county will go blue in 2020 – unless the nominee is Senator Warren or Senator Sanders, whose proposals like “Medicare for All” and free college tuition may not resonate with the work ethic here.

“It does scare me if we end up with one of these giveaway candidates,” says Mr. Demmer, a former county supervisor attending Tom Steyer’s town hall in Dubuque on Friday. “People in Iowa still go out and work for what they have. And that’s the concept of all of rural America. We live by the saying don’t give someone a fish, give them a fishing pole.”

A turnaround story

Dubuque is not your stereotypical Midwestern Trump stronghold, a declining industrial city struggling to reinvent itself. It already has. It went from having the highest jobless rate in America (23%) in the early 1980s to just 1.9% last year, though in poorer neighborhoods it’s twice that and the poverty rate is nearly 12%.

Today, the city of nearly 60,000 is growing, and its downtown – nestled at the base of bluffs along the ice-gray Mississippi – features breweries and boutique yarn shops, art galleries, and cafes selling avocado toast and almond milk lattes. Down by the river, refurbished mill buildings now house condos and lofts, some with waiting lists.

The first city in Iowa to be settled, by an eponymous Quebecois explorer, Dubuque is also a Catholic stronghold that’s home to three colleges and several seminaries. It counts among its most famous residents Olympic medalists, the Hamilton of Booz Allen Hamilton, and a rear admiral in the U.S. Navy who surveyed the Amazon and helped capture Guam.

It is the county seat of one of 31 counties in Iowa that voted for Mr. Obama and then Mr. Trump, the most of any state in the country. The president won Dubuque by just 1.2% – becoming the first Republican presidential candidate to win over the county’s residents since Dwight Eisenhower. In 2018, Democrat Abby Finkenauer, the 29-year-old daughter of a union welder, won them back in her bid for the U.S. House of Representatives.

Ballotpedia, New York Times, Atlas of US Presidential Elections

Lindsay James, a Democratic state representative from Dubuque, says the main issues she hears about from constituents are health care, jobs, and good schools.

“They’ll vote for whoever is speaking to those issues, regardless of party lines,” says Ms. James, adding that she’s talked with numerous Republicans who are caucusing on Monday or planning to vote for the Democratic nominee in November.

The front-runners in the Democratic field have spent considerable effort wooing these voters, making the trek out to this eastern outpost on the Mississippi, some three hours from Des Moines. This past weekend marked the fourth trip to the city for both Pete Buttigieg and Joe Biden, and Andrew Yang’s third in just six weeks.

“I’ve never voted for a Democrat before. Yang is the only one I’d vote for,” says real estate agent Jay Schiesl at a Yang event last Thursday in Dubuque, where every seat was claimed and late arrivals had to stand in the back. “This is the first time I’ll ever caucus. I have to put a ‘D’ next to my name to be able to caucus. Do you know how hard that’s going to be?”

Senator Sanders, Senator Warren, and Amy Klobuchar each made it three times before the impeachment proceedings constrained their ability to campaign in the final weeks before the caucus.

“Contrast that with [Julian] Castro,” says Steve Drahozal, chair of the Dubuque County Democratic Party, who liked the former Housing and Urban Development secretary’s positions but lamented that he – like others who have since been forced to drop out – didn’t recognize the importance of this part of the state. “He could not find his way out of central Iowa.”

Thanks in part to fresh faces like Mr. Yang, who appears to have attracted a lot of new folks beyond the usual core Democrats, engagement is way up this year, says Mr. Drahozal. The county party’s cash reserves have more than doubled, and the email list has grown by close to 50%.

“My own brother, who is 46 years old, has never caucused and he’s going to caucus for the first time this year,” he says.

Nathan Thompson, Democratic chair in Winneshiek County – the only other Trump county that Representative Finkenauer won back – echoes that. Crowds at Democratic events have increased by about a third, and the county party’s financial situation is about twice as good as before, he says. Mr. Buttigieg drew nearly 1,000 people last summer.

“The story over and over in Iowa with Democrats losing is, we fail in the rural areas,” he says. “The Warren and Buttigieg campaigns have made a real effort to get outside of [the county seat of] Decorah and hit some of those rural doors.”

“You can’t have missed how important this election is”

Emily and Rick Reeg are among the more than 700 people who turned out for a Buttigieg town hall in Dubuque this weekend, exceeding the expectations of the campaign, which ran out of stickers for attendees checking in.

Ms. Reeg, a first-grade teacher, is all in for Pete – a precinct leader who likes his “honesty and integrity.” Her husband, a former business owner who voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, is more hesitant. Having lost a cousin who was killed by a suicide bomber in Iraq, he says his first priority is support for the military.

“That’s big for a lot of us,” says Mr. Reeg, who is deciding between Mr. Biden and Mr. Buttigieg, a Navy Reserves intelligence officer who served seven months in Afghanistan.

“I like a lot of Trump’s policies, to be honest, especially with foreign policy,” he says. “He’s willing to stay in communication with Putin and North Korea. We can’t just box them out like Obama. But Trump’s mouth,” he adds, shaking his head.

A Buttigieg campaign worker comes around with a fishbowl and white notecards, asking attendees if they would like to submit a question for the candidate. Mr. Reeg says yes, I’d like to ask him how he would respond to North Korea. As the campaign worker transcribes Mr. Reeg’s question, he clarifies that he specifically wants to know whether a future President Buttigieg would engage in a dialogue with Kim Jong Un.

Waiting in line to get in, Greg Orwoll, who has voted Democratic since the 1990s but couldn’t bring himself to cast a ballot for Hillary Clinton, is now repentant for having voted for a third-party candidate in 2016 (Jill Stein, because her name was first on the list).

“I thought [Clinton] was going to win. I just didn’t want her to have such a huge majority, which she thought she’d have,” he says. His wife, Shirley, leans in and whispers, “That’s why we lost!”

“You’re right, I know. Live and learn,” he says. “Personally, I’m supporting a ham sandwich on rye if it’s the Democrat.”

In 2016, he says, people weren’t passionate about the Democratic ticket – not like some Trump voters, who would have driven through a snowstorm to vote for their candidate. But this year, there’s passion on the Democratic side – and anger at Mr. Trump.

“I think that’s going to be really powerful in November,” says Mr. Orwoll, squinting in the bright sunlight reflecting off the snow. “Short of living under a rock, you can’t have missed how important this election is. You just can’t have missed that.”

Ballotpedia, New York Times, Atlas of US Presidential Elections

In Trump plan, Arab Israelis see assault on their identity

In a region of clashing identities, Arab citizens of Israel have long occupied a delicate position straddling two worlds. We wanted to look at why a peace plan is seen as challenging their hard-won gains.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

President Donald Trump’s Middle East peace deal suggests borders be redrawn so 300,000 Arab citizens of Israel become part of a future Palestinian state. Their swift and furious answer, which cuts to the core of their complex identity, has been nearly unanimous: No way.

Despite the ongoing challenges they face, Israeli Arabs are more economically and socially integrated now than at any time in Israel’s history. And they’re surprised that an idea first floated on Israel’s extreme right has now been adopted by the White House as one of the ways to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They see it as an attempt to delegitimize their citizenship, and view the very idea as both racist and illegal.

The controversy is prompting a conversation about those things many Palestinians do value about being part of Israeli society. “We are part of the country’s job market; we have our social and economic status here,” says Yousef Jabareen, an Arab member of parliament. “This is about trying to question our status as if we are not really full citizens.”

Says Salam Ayash, a truck driver: “We are not the problem. We are actually part of the solution to this conflict. We can be a bridge between our nation and our state.”

In Trump plan, Arab Israelis see assault on their identity

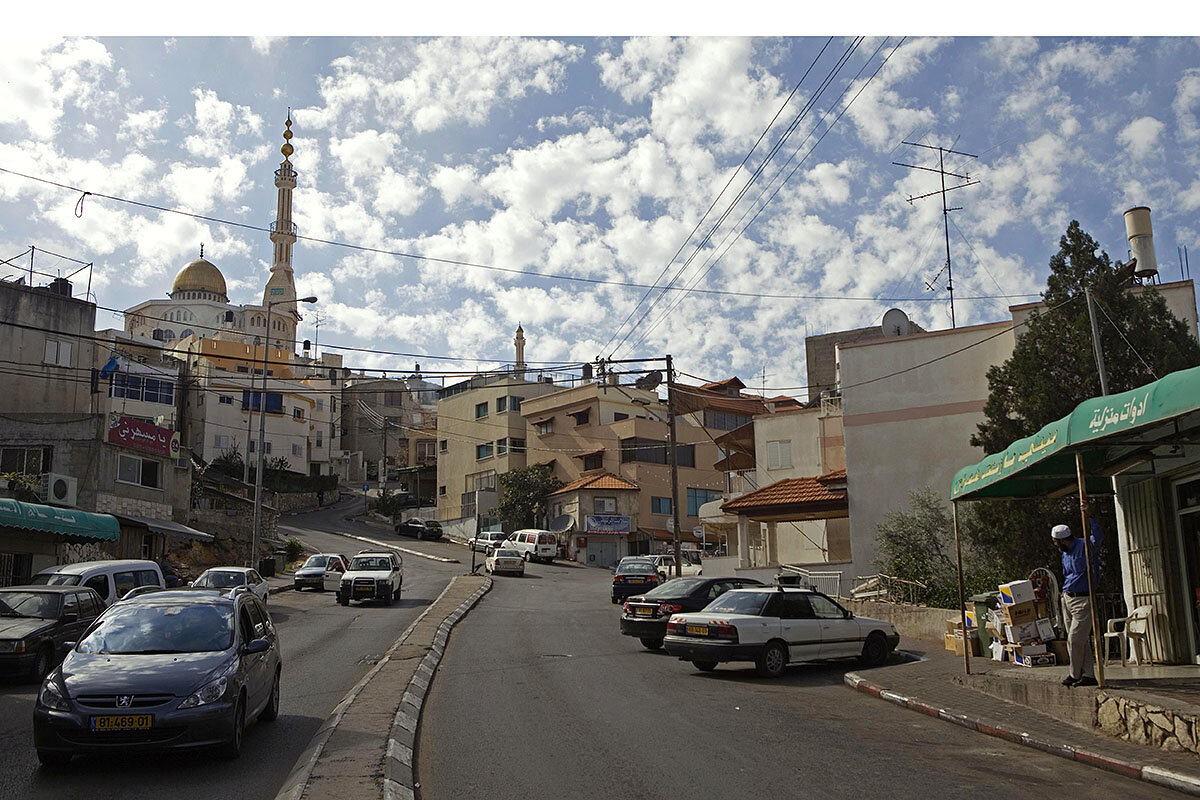

It’s called “the Triangle” – a cluster of Arab towns and villages nestled along a valley and on the slopes of adjacent hills in north-central Israel, across the border from the northern West Bank.

President Donald Trump’s new Middle East peace deal suggests the borders be redrawn so the 300,000 Arab citizens of Israel who live in the Triangle, a fifth of the country’s Arab minority, become part of a future Palestinian state.

The swift and furious answer to that proposal from those who live there, one that cuts to the core of their complex identity, has been nearly unanimous: No way.

Despite the ongoing challenges they face, Israeli Arabs – or Palestinian citizens of Israel, as they increasingly identify – are more economically and socially integrated now than at any time in Israel’s history.

And they, along with some Jewish Israelis, are surprised that an idea first floated on the country’s extreme right has now been adopted by the White House as one of the ways the Israeli-Palestinian conflict might be resolved.

They reject the proposal – part of an overall plan heavily tilted toward Israeli negotiating positions – as an attempt to delegitimize their citizenship, and view the very idea as both racist and illegal.

“It shows how the state of Israel views us – as a fifth column. That’s why they want us swapped out,” says Diana Buttu, a political analyst and Palestinian citizen of Israel.

“It’s not that inside Israel is great, because we are not treated as equals and there is lots of discrimination. But Israel is a state. The difference is that this is about being pushed into a statelet,” she says, describing her take on the future Palestinian state laid out in the plan.

“It’s not going to be a place with freedom of movement, a developed economy, or infrastructure development,” she says. “It’s a way to push Palestinians into a repackaged form of occupation.”

A complex identity

Yousef Jabareen, a member of parliament from the Joint List, a coalition of Arab parties that joined forces in recent elections to become the third-largest party in Israel, lives in Umm el-Fahm, the largest town in the Triangle. He says he fears the real reason for the plan is not to promote “peace” but to provide a convenient way for Israeli hard-liners to have a country with fewer Arab citizens.

Yet despite the challenges Israeli Arabs face as a minority, the controversy over the Trump plan is prompting a conversation about those things many Palestinians do value about being part of Israeli society – among them, their role fighting for equality and social justice and their growing visibility as university students and in the medical and other professions.

Arab citizens, Mr. Jabareen argues, can still retain their historic Palestinian national identity while maintaining their identity as Israelis.

“For over 70 years we have built social and economic ties within our Arab community in Israel,” he says. “We are part of the country’s job market; we have our social and economic status here. You cannot suggest such a dramatic change without consulting the community.

“This is about trying to question our status as if we are not really full citizens. This is not how a democratic country deals with its citizens.”

Mr. Jabareen, a former law professor, argues that such a dramatic change in citizenship status would be illegal without the consent of the citizens in question. The wording of the Trump plan does say that involved parties would have to agree to it.

Painted as the enemy

While the peace plan was announced with much fanfare at the White House on Tuesday, no Palestinians accompanied President Trump or Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

After news of the Triangle proposal broke, Ayman Odeh, head of the Joint List, warned proposals for further population transfers might follow, involving Arab Israelis in other parts of the country.

“What about those who don’t live by the West Bank border? They could be part of the next plan,” he said.

The Trump plan was announced at a time when Palestinian citizens of Israel increasingly feel painted as the enemy by Mr. Netanyahu and other hard-liners. Mr. Netanyahu, who is fighting for his political survival – he was indicted on corruption charges the same day the Mideast plan was announced – has repeatedly suggested, especially close to recent elections, that Arab citizens pose a threat.

In March, Israel heads to its third election in a year – the result of no one party winning decisively enough to form a governing coalition.

After the most recent election, in September, there was speculation the Joint List might support Mr. Netanyahu’s political rival – the Blue and White Party headed by Benny Gantz, a retired general.

Arab politicians are also arguing the proposal to transfer the Triangle to Palestinian control is Israel’s way to get rid of Arab voters by what amounts to gerrymandering.

Backlash among Jews

Opposition to placing the Triangle area under future Palestinian rule has also come from Jewish Israelis across parts of the political spectrum.

Ofer Shelah, a Knesset member from the center-right Blue and White Party said, invoking both Jewish and Arab towns to make his point, “One thing must be ruled out: Israeli citizens and communities will not be transferred to the Palestinian state. Neither Kfar Saba nor Tira, neither Kochav Yair nor Taibeh. The very idea is obscene.”

On Friday, the editorial board of the left-wing Haaretz newspaper published its take on the plan under the headline “Israeli Arabs Are Not Pawns.”

Israel, the editorial says, must “reject out of hand this warped idea of the Washington peacemakers, who aren’t familiar with the fabric of life in Israel. … The overwhelming majority of [Arab Israelis] see themselves as an inseparable part of Israel. They were born, raised and educated in Israel, where most of them want to keep living. … If Arab Israelis are temporary citizens, the state shouldn’t expect their loyalty and integration. If Israel wants to be loyal to its citizens, all of them, it must immediately drop the dangerous and outrageous idea to drive this community out of here.”

Palestinian Israelis as bridge

Salam Ayash, a truck driver from Umm el-Fahm, has very practical questions of the Trump plan.

“What is this Palestinian state? Does it have border crossings? Does it have an airport? A port? Will it be like living in Gaza, which is under a closure and you cannot come and go as you want?” he asks.

“We are used to this country, used to going to the sea, and are connected to its hills and land,” he says. “Since 1948 when Israel was founded we have become a community of our own of Arab citizens.”

Noting that families live in various parts of Israel, Mr. Ayash continues: “You cannot separate us from each other … and we are a loyal minority to the state. We helped build this country. Our doctors treat people in its hospitals, our professors teach in its universities. You cannot cut us out because someone like Trump or Netanyahu decides to.

“We are not the problem,” he says. “We are actually part of the solution to this conflict. We can be a bridge between our nation and our state.”

A deeper look

Beyond the picket fence: How one city creates affordable housing

The single-family home was the American ideal for so long that regulations grew to favor it. Our writer went to explore one city’s act of responsiveness to a changing demand.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Minneapolis is the scene of what may be the nation’s most ambitious urban experiment in tackling housing affordability.

The overhaul here ends “single-family zoning,” which has long reserved sections of the city – like others around the United States – for detached one-family homes. The city’s comprehensive “2040 plan” includes new protections for renters, new demands on developers, and is meant to address inequality and climate change.

The housing revolution wasn’t sparked overnight. First came practices of racial discrimination as an overt feature of real estate deeds in many neighborhoods. That was followed by several decades of underinvestment in new housing combined with sharp declines in federal spending on low-income housing.

Political analysts say Minneapolis took reforms further than most because of a blend of liberal politics, a tradition of civic engagement, and an increasingly activist city council. But there’s plenty of skepticism in residents who say, for example, that the new rents aren’t cheap – bringing worries of gentrification rather than housing-cost relief.

City officials say the needs of historically disadvantaged city residents are not being forgotten. “We are doing a lot,” says Mayor Jacob Frey. The goal is “to make sure that the precision of our solutions matches the precision of the harm that was inflicted.”

Beyond the picket fence: How one city creates affordable housing

A decade ago, as a newly minted college graduate with a job in the film industry, Linnea Goderstad saw career opportunities and a creative vibrancy in New York City. What she didn’t find was a path toward affordable housing.

After abiding the rigors of an expensive one-bedroom apartment for a few years, Ms. Goderstad and her husband, David Blomquist, decided a change was needed. They moved back to their native Minnesota, calculating it would combine proximity to family, promising career paths of its own, and – importantly – the opportunity to live in something other than a platinum-priced shoe box.

The journey has been promising. They’ve found good jobs and are now several years into owning a tree-fringed town house in a neighborhood they love in downtown Minneapolis. But if anything, what surprised them was how hard it was to find that dwelling, even after moving to a place far from robust coastal real estate markets such as Silicon Valley and New York. Between their own student debt and tightness in the supply of homes here in Minneapolis, they had to exercise both patience and bidding-war boldness to land their town house.

“You shouldn’t have to have an MBA to buy a house,” says Ms. Goderstad. “We’ve messed up as a society if that’s where we’re at.”

The city around her broadly agrees. Minneapolis is now the scene of what may be the nation’s most ambitious urban experiment in trying to tackle the challenge of housing affordability.

Officials here are starting to implement an overhaul that ends “single-family zoning,” which has long reserved large sections of the city – like others around the United States – for detached one-family homes. In tandem, the city’s comprehensive “2040 plan” calls for new protections for renters, new demands on developers, and other moves to preserve and expand a now-thin supply of affordable housing.

Time for different ideas

The impetus behind all this, in a city increasingly led by younger, post-boomer generations, isn’t merely about rent levels and land prices. It’s also rooted in ideals about inclusiveness and community – whether across racial lines, among renters and owners, or in the form of housing units of varying sizes and styles, from studios to homes for multigenerational families or cooperative ownership models.

“We’ve kind of idolized that you will have a single-family home in the suburbs. That’s a bar you are trying to reach,” says Ms. Goderstad. “That’s great for people who love that lifestyle.” But, she notes, it’s also time to embrace “different ways to have a home.”

For many here, the vision is also about environmental sustainability, a future where urban vibrancy aligns with planet-friendly lifestyles. The Minneapolis City Council approved the 2040 plan in December 2018. In the past few months, key steps have been taken to begin implementing it, including encouraging the conversion of single-family homes to duplex and triplex dwellings.

Other states and communities around the nation are watching the experiment here in the mittened North as they struggle with housing woes of their own.

“We are in a crisis that has actually been a long time coming and building progressively over time, where we’re seeing housing costs continue to grow faster than incomes in most metropolitan areas across the country,” says Solomon Greene, a housing policy expert at the Urban Institute in Washington. “There is no silver bullet. ... Multiple solutions are going to be necessary.”

That’s why he sees the Minneapolis venture as so important. While it’s far from the only urban area testing or considering new policies, it is one of the most aggressive in trying to expand the supply of homes through greater density. He also praises the city for combining this with initiatives targeted toward low-income residents.

Yet beneath it all, the question remains: Can any city really ease the affordable housing crunch?

Other costs of living

Mr. Blomquist remembers the moment a sense of housing insecurity first hit him. He was riding a bus toward New York City to start his career after graduating from college in Minnesota in the spring of 2008. Word reached him by cellphone: One of the people he would be living with had lost his job, so his plan to sublet a bedroom was disappearing.

“Oh, I’m homeless,” he recalls thinking.

A few sublets later, life became more stable. He navigated from an AmeriCorps internship into health care work, and the couple soon had their own apartment. But experiences like theirs – the challenges of finding housing, of saving money while also paying big college loans – have helped shape a generation.

As of 2015, millennials ages 25 to 34 had achieved a homeownership rate of 37%, well below the 45% seen by baby boomers and Gen Xers at that same age range, according to a 2018 analysis by the Urban Institute.

In part, this is the story of a generation that entered adulthood during a deep recession and may never quite catch up financially from those effects. But it’s more than that.

For many Americans, middle-class lifestyles have grown harder to sustain as costs of college, health care, and housing have risen faster than paychecks. Half of all renters now spend more than 30% of their income on housing. Urban land values keep rising. These forces transcend any one generation.

There is progress. Incomes and homeownership rates are growing for young working-age Americans, census data show. Many millennials are successfully building careers in cities where home prices aren’t as prohibitive as in San Francisco or New York.

Low supply, between the coasts

Yet even in places like Minneapolis, a top-ranked city for millennial homeownership, it can be hard to find housing without a software engineer’s salary.

Ms. Goderstad and Mr. Blomquist discovered this when they began seeking a place of their own in 2016. They wanted a town house, both because it was more affordable and because they wanted to avoid yard maintenance. But they soon learned how many others wanted the same thing. They finally landed a deal by pouncing quickly, with an offer that was a bit above the asking price.

“For me, I was motivated more than anything else by climate change,” says Ms. Goderstad, referring to their choice to live in a place where she can walk, bike, or take mass transit to local attractions or to her job in event planning. Cities, she says, should be building “more complete neighborhoods,” walkable hubs that blend residences with commerce and cultural amenities.

For her, that includes a more diverse housing mix – from traditional dwellings to cheaper options like “co-housing” for young singles – suited to the varied needs of an increasingly diverse population.

Widening the scope

The city’s 2040 plan embodies those goals. It’s not just about housing but also about addressing inequality and responding to climate change.

Mayor Jacob Frey, a millennial himself, says that while younger voters have embraced these overlapping goals, the vision isn’t exclusive to one generation.

“The model has changed. The American dream of the 1950s ... where the whole goal was white picket fence in the suburbs with the 45-minute commute to work and the corner office, is dead – or at least it’s not as treasured,” he says. “Young people want to live in a dense and vibrant city. In many cases they don’t want to own a car. They want to work in a collaborative atmosphere and live in a beautifully diverse city.”

The eruption of a housing revolution here wasn’t sparked overnight. First came practices of racial discrimination as an overt feature of real estate deeds in many Minneapolis neighborhoods. Then local experts say there were several decades of underinvestment in new housing, combined with sharp declines in federal spending on low-income housing.

In the 2000s, a boom-to-bust housing disaster engulfed the nation just as the giant millennial generation was starting to think about sofas and soaker tubs. Even prior to Mr. Frey’s election as mayor in 2017, Minneapolis was pushing for action. Housing had emerged as a critical issue.

In 2014 the city moved to legalize “accessory dwelling units” like garages or basement apartments. Then came an easing of rules so apartment developers didn’t need to devote so much space and money to parking spaces.

Lisa Bender, a new council member at the time who had campaigned on housing reform, says a common concern was that “our city is growing and we have a housing supply problem that needs to be addressed.”

All the activists

But that’s the case in many cities. Political analysts say Minneapolis took zoning and other reforms further than most because of a blend of liberal politics, a tradition of civic engagement, and an increasingly activist city council.

While the interest in new kinds of housing wasn’t limited to millennials, the shift in thinking had a demographic element. (Mr. Frey was elected to the council in 2013, alongside Ms. Bender, also in her 30s at the time.)

Ms. Bender says an upwelling of community involvement – countering the perennial clout of “not in my backyard” sentiments – came from groups focused on racial justice and transportation, not just housing.

Some of the energy also came from politically active citizens like John Edwards. A graphic artist who moved to Minneapolis in 2012, he recalls attending a public hearing on housing, soon after Ms. Bender was elected to the council.

The focus was on a proposed six-story apartment building at a major intersection near bus routes. Beneficiaries might include young renters like him, yet “there was just one kind of person” who showed up to voice opinions, Mr. Edwards says. Those were longtime homeowners who opposed it.

“That was shocking to me,” he says. He started a blog and Twitter feed about his own neighborhood, known locally as “the Wedge,” building a following in part by putting a comedic edge on his posts.

Mr. Edwards also helped found a group called Neighbors for More Neighbors (N4MN) to formally counter NIMBY viewpoints.

As city officials were shaping the 2040 plan with public input, blue or purple N4MN signs began to pop up on lawns or front stoops around the city, competing with red ones saying, “Don’t bulldoze our neighborhoods.” Ms. Goderstad became an active member of the N4MN group.

“One thing that really stood out to me at the end of the process [was] just how many people turned out to testify in favor of the 2040 plan,” albeit alongside many naysayers, says Mr. Edwards. “In my first couple of years in Minneapolis, it was rare to see anyone young testifying.”

Why it might not work

If there’s optimism in Minneapolis about housing, there’s also plenty of skepticism. Some residents, while saying they share the goal of affordable housing, don’t want to see the city zoned for greater density in such a broad-brush way. The passions are evident when the City Planning Commission meets about twice each month to review projects or weigh in on overall policies.

“I plead with you all to consider what the homeowners are saying to you,” one city resident told commissioners at a recent meeting, urging opposition to a proposed apartment complex next to her home. “These apartments aren’t for people working at McDonald’s,” she adds, casting doubt on the notion that new construction does much for affordability.

That’s an oft-repeated concern. While new construction can help the city by adding to the overall housing stock, the rents aren’t cheap – bringing worries of gentrification rather than housing-cost relief.

Nichole Buehler, of the Harrison Neighborhood Association, shows up at the meeting to argue that an apartment development will displace some older homes that are truly affordable. “We need to really protect the affordable housing that we have,” she says in an interview later.

The 2040 plan aims to pursue both goals – more housing overall and more units for low-income renters – in part by what’s called “inclusionary zoning.” The idea is to call on developers to make a fraction of their apartments affordable to people of modest incomes. Some locals say the measure is too aggressive and may backfire.

“Don’t chase away private investment,” Steve Cramer, a former city council member who now heads the Minneapolis Downtown Council, a business association, tells commission members at the meeting. “Overregulated markets are less affordable markets.”

Skepticism of private investment

Another city policy – pursuing an overhaul of its existing stock of federally supported public housing – also draws fire.

Facing a backlog in maintenance of its single-family homes, the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority has outlined plans to roll them into a new nonprofit, opening the door to private investment for their renovation. Although the housing authority is pledging that rents will rarely increase as a result, many residents are mobilizing in opposition, concerned about displacement or rising costs.

“There wasn’t any guarantee that we will be staying in this home,” says Hibaq Abdullahi, who is awaiting details on what may happen to the rent-subsidized home where she and her Somali immigrant family live.

“We have a city [leadership] that is failing the people that it’s elected to serve,” adds Ladan Yusuf, another Somali American who has organized protests over the issue. She argues that the city could afford to maintain the homes without bringing in the private sector and that the move will benefit developers at the expense of low-income tenants.

City officials say the needs of historically disadvantaged city residents are not being forgotten.

“We are doing a lot,” says Mayor Frey, referring to steps such as boosting the city’s own funding for subsidized housing and protecting tenants citywide, possibly with rent-stabilization rules. From those moves to zoning reform, he says, the goal is “to make sure that the precision of our solutions matches the precision of the harm that was inflicted” by decades of racially biased policies.

An easier rehab

On a nondescript street lined with single-family homes, the future of Minneapolis housing is beginning to take shape.

Bruce Brunner now has a new career as a landlord after years of working at the Minneapolis-based retailer Target. He’s busy rehabbing a worn-out home here – not just remodeling it but converting it from a one-family dwelling to a triplex.

It’s one of the early instances of the 2040 plan’s vision becoming real on the ground. As the city moved in November to implement key zoning changes in that plan, it gave Mr. Brunner the ability to do this conversion “by right” without the former uncertainty and bureaucratic hurdles.

“I was able to proceed without applying and pleading my case for a variance,” he says.

Inside the house, a contractor is hard at work amid stacks of lumber, some power tools, and loosely hung construction lights.

But soon, one spacious floor will become a four-bedroom apartment, and the other will be split into two more units – a one-bedroom and a two-bedroom.

By itself, the remodel will only be a few new units. The idea, though, is that this will be multiplied many times over, filling in for what many call the “missing middle” in American housing.

“Over time we’re going to add and add and add,” predicts Mr. Brunner, who’s a fan of the 2040 plan. “As there’s more supply, the premium charged [by landlords] comes down because people have more choice. It does change the dynamic.”

The result probably won’t be falling prices, some real estate experts say. But it could help contain housing inflation.

Crisis at the bottom

“The 2040 plan to its credit does appear to be attempting to create affordability and housing opportunities across the city,” says Margaret Kaplan, president of the Housing Justice Center in Minneapolis. But “I don’t think that there’s enough in there in terms of tools and resources and programs to address the critical shortage of housing that’s affordable to families making less than $30,000 a year. It’s the hardest thing to do, but it’s also where the greatest shortage exists.”

She and other experts call for more public funds to support low-income housing, whether through vouchers or building public apartments.

But other steps could also help improve affordability for households at various income levels. Those could range from credit-score tutorials to streamlining the regulations facing builders. Another area of promise: cutting home-building costs through modular or factory-based construction.

An eye on what’s next

Local leaders will surely have to keep adapting their plans based on the city’s experience and the vagaries of electoral politics. But Mr. Greene of the Urban Institute says experiments here could lay down a marker.

“A lot of other states are looking ... to see what happens and whether the sky collapses, which it won’t,” he says. In fact, Oregon has already enacted a law that will effectively end single-family zoning starting in 2021. California is trying to encourage more building across the state. Localities from Arlington, Virginia, to Los Angeles have also begun opening the door to more backyard cottages and other “accessory dwelling units.”

To Ms. Goderstad and Mr. Blomquist, every duplex or triplex in this city counts.

That was the kind of home they could afford, after all. And whether it’s for renters or owners, they want other young people to be able to live in the city.

“We have our problems, our inequalities,” Ms. Goderstad says. She was saddened when one friend who had hoped to live near her ended up moving out of town instead to find an affordable house.

“What makes me hopeful is just the fact that we were able to pass the comprehensive plan that we did.” It’s a vision not just about economics but about changing lifestyles – a point that resonates with bicycle commuters like her. “We need housing of all sorts.”

Price of Rwanda’s clean streets? Detained children, NGO says.

What happens when a nation that’s been a poster child for progress appears to slip? In reporting about homeless children, our writer saw a troubling pattern beneath Rwanda’s glossy reputation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In the quarter century since Rwanda’s horrific genocide, the country has become a frequently praised “success story,” applauded for its rising measures of health, education, well-being – and clean, safe streets. But that order is maintained, in part, by a network of squalid facilities for detaining people accused of “deviant behaviors,” including homeless children, according to a report released last week by Human Rights Watch.

Ostensibly, the children are then taken to rehabilitation centers to be taught vocational skills. But many of the children interviewed by the rights group said they were released back onto the streets, and most said they had been beaten.

The situation can be seen as a microcosm of Rwanda’s larger paradox. The tiny “country of a thousand hills” has experienced, in many ways, a dazzling transformation. Yet the miracle has always shown cracks, and is maintained, many critics say, at the point of a gun. President Paul Kagame’s critics have been violently suppressed, and he has won in excess of 90% of the votes in every election.

“We want to push the international community to ask tough questions of Rwanda,” says Lewis Mudge, of Human Rights Watch. “And to the government, we hope this will prod them in the right direction.”

Price of Rwanda’s clean streets? Detained children, NGO says.

As advertisements for a country go, Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, is top of the class. Visitors glide into town from its tidy international airport on smooth, pothole-free roads, passing glossy high-rises, luxury hotels, and the flashing neon dome of a $300 million conference center. In Kigali, often dubbed “Africa’s Singapore,” the streets stay swept, the hedges stay trimmed, and the garbage stays in its cans. At night, locals and tourists alike walk with their gazes fixed on the glow of their cellphones, unworried about petty thieves or worse.

But like much of Rwanda’s success over the 25 years since the country’s genocide, the order of its capital has come at a heavy human cost. To keep its streets clean, the Rwandan government relies on a network of squalid detention facilities where homeless people, beggars, informal street vendors, and others accused of “deviant behaviors” can be held for months without charge, according to a report released last week by Human Rights Watch (HRW), which has documented abuses in these facilities for more than a decade.

Among the victims, according to the most recent report, are likely hundreds of homeless children who have been held at Kigali’s Gikondo Transit Center, where they are routinely beaten and denied access to toilets, sufficient food, and clean living quarters.

“There’s a high price to pay for Kigali’s image as a pristine city, and it’s being paid by society’s most vulnerable,” says Lewis Mudge, the Central Africa director for HRW. “We shouldn’t forget that one of the reasons the city is so clean is because of this practice of routinely rounding up people deemed undesirable.”

Rwandan Minister of Justice Johnston Busingye did not respond to the Monitor’s request for comment, but told Rwandan media outlet KT Press that the HRW report was “politically motivated” and that it was “insane for anyone to suggest that the government is getting rid of its unwanted to keep the streets clean … ignoring the progress we have made in turning former delinquents into useful citizens.”

But the situation for homeless children in Kigali, indeed, can be seen as a microcosm of Rwanda’s paradox more generally. The tiny “country of a thousand hills” is, in many ways, one of the modern world’s most dazzling success stories.

In the span of a few short months in 1994, nearly 1 million Rwandans were murdered, many by their own neighbors, in one of the most brutal mass killings of the 20th century. But in the years since, Rwanda has shot up the charts on global measures of health, education, and well-being, earning it vaunted status among the world’s development titans. (“I hope many African nations will emulate what Rwanda is doing,” said then-United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in 2013, congratulating the country on its majority-female parliament.) Its wiry, bookish president, Paul Kagame, who is credited with leading that revolution, is a darling of the Davos set, regularly lauded by global institutions and fellow leaders. In 2018, Forbes named him its “African of the Year.”

But the Rwandan miracle has always shown cracks. It is maintained, many critics say, literally at the point of a gun. Mr. Kagame’s critics have been violently suppressed, and on several occasions, assassinated, although the government denies responsibility. He has won in excess of 90% of the votes in every election he has run. And independent analyses, including one by the Financial Times, have suggested that some of the figures used to mark Rwanda’s tumbling levels of poverty were intentionally manipulated by the country’s statisticians to show a more dramatic level of progress.

And then there are the much-celebrated clean streets.

“Kagame is fantastic at PR, and he knows that visibly his country looks a lot better than its neighbors, and that to international observers, that matters,” says Stephanie Wolters, an analyst on the Great Lakes region of Africa with the South African Institute of International Affairs. “Many donor countries and international organizations simply aren’t interested in scrutinizing the situation further.” And they have other reasons not to look too closely, she says, given Rwanda’s stability in a rough global neighborhood.

Once a month, all Rwandans participate in compulsory neighborhood cleanups called umuganda. Under Rwandan law, meanwhile, anyone exhibiting “deviant behaviors” in its streets, which it describes as “prostitution, drug use, begging, vagrancy, informal street vending, or any other deviant behavior that is harmful to the public,” can be rounded up and kept for two months without charge in one of the country’s transit centers.

Last year, Human Rights Watch spoke to 30 children held at the transit center, most of whom said they had been beaten there.

“The police captain with three stars on his uniform hit me at least 20 times with his police club,” said a 15-year-old girl arrested in April 2019. “He said that as long as we’re in the streets, he’ll keep beating us.”

Ostensibly, centers like Gikondo are temporary stops before children living on the streets and others are taken to rehabilitation centers to be taught vocational skills. But many of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were never transferred to those centers, and instead released after an arbitrary length of time back onto the streets, beginning the catch-and-release cycle again.

“They put us in a car, and everyone was dropped off where they had been arrested. That was the fifth time I was in Gikondo,” explained a 16-year-old girl.

Although Rwanda’s case is extreme, it is not the only country to detain people experiencing homelessness to keep them off the streets. In many countries, major sporting events provide the pretext. Ahead of the 2008 Olympics, officials in Beijing relocated homeless residents to centers outside the city. Before the Athens games four years earlier, several Roma communities were forcibly evicted or displaced. And in Brazil ahead of the 2016 Rio games, children’s advocates raised alarm about homeless youths being detained arbitrarily.

Mr. Mudge said that he is hopeful that Rwanda’s interest in maintaining its vaunted international image will compel the country to respond to HRW’s demands, which include closing Gikondo permanently. After previous HRW reports on the center in 2006 and 2016, the government instituted some reforms, he says, but they ultimately proved shallow.

“We want to push the international community to ask tough questions of Rwanda,” he says. “And to the government, we hope this will prod them in the right direction.”

Listen

What makes a strong America? Strong Americans.

We’re always looking for people working at the intersection of compassion and solutions. In this audio story, Editor Mark Sappenfield talks to the authors of “Tightrope.” Have a listen. (And read the Monitor’s review of the book here.)

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 19 Min. )

-

Samantha Laine Perfas Story Team Leader

Husband-wife duo Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn have won Pulitzer Prizes for their international work, from their coverage of the Tiananmen Square massacre in China to Mr. Kristof’s reporting on the Darfur genocide in Sudan. South African archbishop Desmond Tutu has even called Mr. Kristof an “honorary African” for his work alleviating suffering on the continent. But their new book, “Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope,” presented a new challenge for the couple: reporting on a humanitarian crisis in their own backyard.

“One of the challenges in writing ‘Tightrope’ was that we were a little bit afraid that readers would be so focused on the mistakes that some of the people had made that they wouldn’t see through to the fundamental humanity of these people,” Mr. Kristof says in a studio interview at the Monitor. The book begins in Mr. Kristof’s beloved hometown, Yamhill, Oregon, as it chronicles the wave of drugs, crime, poverty, and hopelessness sweeping across the town. It’s a downward spiral seen in much of rural America, even as the United States boasts an overall growing economy.

Ms. WuDunn shares in the interview that the reason for the book is not just to highlight all that is wrong with a country in crisis, but to examine possible solutions. And many of the solutions involve investing in the nation’s human capital. “If we don’t raise strong Americans, how can we have a strong America?” she says.

What makes a strong America? Strong Americans.

Reaching for hope: An interview with Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn

Husband-wife duo Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn have won Pulitzer Prizes for their international work, from their coverage of the Tiananmen Square massacre in China to Mr. Kristof’s reporting on the Darfur genocide in Sudan. South African archbishop Desmond Tutu has even called Mr. Kristof an “honorary African” for his work alleviating suffering on the continent. But their new book, “Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope,” presented a new challenge for the couple: reporting on a humanitarian crisis in their own backyard.

“One of the challenges in writing ‘Tightrope’ was that we were a little bit afraid that readers would be so focused on the mistakes that some of the people had made that they wouldn’t see through to the fundamental humanity of these people,” Mr. Kristof says in a studio interview at the Monitor. The book begins in Mr. Kristof’s beloved hometown, Yamhill, Oregon, as it chronicles the wave of drugs, crime, poverty, and hopelessness sweeping across the town. It’s a downward spiral seen in much of rural America, even as the United States boasts an overall growing economy.

Ms. WuDunn shares in the interview that the reason for the book is not just to highlight all that is wrong with a country in crisis, but to examine possible solutions. And many of the solutions involve investing in the nation’s human capital. “If we don’t raise strong Americans, how can we have a strong America?” she says.

Read the Monitor’s review of “Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope.”

Note: This recorded interview was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears, but we understand that is not an option for everybody. You can find the audio player above. For those who are unable to listen, we have provided a transcript of the story below.

AUDIO TRANSCRIPT

NICHOLAS KRISTOF: The reason we chose the title “Tightrope,” it goes to your issue that there are absolutely people who managed to cross the tightrope, and bravo to them. But if you’re on the tightrope, then maybe you’ll make it across, but one stumble and that’s it. There’s no safety net.

MARK SAPPENFIELD: Hello, I’m Mark Sappenfield editor of The Christian Science Monitor, and today I have the great pleasure of inviting authors Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn into our studio to talk about their new book, “Tightrope.” They’ve both reported for The New York Times in conflict zones around the world and were even the first husband-wife pair to win a Pulitzer for their work. More recently, they’ve coauthored a book that explores issues closer to home. It’s titled “Tightrope,” and the book shares the stories of people struggling with joblessness and the loss of hope around the United States. But it focuses particularly on the small town of Yamhill, Oregon, where Nicholas grew up. He’s lost many friends and neighbors in Yamhill to early deaths from addiction, illness and other so-called diseases of despair. But Nicholas and Sheryl also uncovered something else: stories of resurgence and recovery that offer credible hope that there are solutions for a nation in crisis. And we’ll talk about some of those stories today.

So, Nicholas, you’ve reported around the world in conflict zones and developing countries. What was it like reporting in your own backyard?

KRISTOF: This was a lot more difficult because we’d spent a lot of time in, say, refugee camps, interviewing people. And then you have a certain emotional armor when you hear terrible stories. But in this case, we were going back to ... And essentially what happened was we were covering humanitarian crises abroad and then we’d go back periodically to my beloved hometown of Yamhill, Oregon, where my mom is still on the family farm. And we saw this humanitarian crisis unfolding there. And initially, we didn’t really know how to process that. And then gradually we saw that this was just a microcosm of a national problem. And, you know, Mark, it is so much harder to talk to kids you’ve grown up with, who you competed with on the high school track, you passed notes to in class, you had crushes on and talk to them about drug abuse, homelessness, an attempted suicide, and the struggles with their children. You know, it was also tough because we cared deeply how they will perceive it. And also, I love Yamhill and I don’t want people just to think of it as this place where everybody’s cooking meth and falling apart. It’s much, much more than that. And yet we think that America is not adequately focusing on how much suffering there is out there. And we thought that this would be one way of telling that story and highlighting the problems out there.

SAPPENFIELD: Sheryl, one thing that is so apparent in the book is that we are really invited to take a journey with Nicholas because we’re going back to a place that you loved so much, where you grew up, where you have friends. But, you know, it’s very hard to read the book and not feel like you’ve gone on a journey too. Talk a little bit about the journey that you went on through this book and how it changed, and how you dealt with these things.

SHERYL WUDUNN: Well, of course, I’ve been going back to Yamhill for decades now. And, you know, after, even before we got married, I’d already gone to the farm and started going to Yamhill and every year we’ve gone back there, so, and we’ve lived there as well. So I have come to know a lot of Nick’s friends and we would see them all the time, and also know the people who worked on the farm, some of whom we actually portray in the book. So this one family, the Knapp family is particularly a striking family. This is one where Farlan, the oldest, is the one who was on the bus with Nick. And he and his four siblings would, you know, tumble into the bus, No. 6 school bus. And, you know, they would be rambunctious and happy and very funny. And they were, you know, just happy kids on the bus with the futures ahead of them. Their father was a union pipe layer. And the mom worked on a tractor with the little one Keylin in tow because she didn’t have any child care. And so their futures were ahead of them. And then over the years, what happened was that since the mother and the father hadn’t really had much of an education, like not even elementary school. Well, you know, why should the kids? They don’t need schooling. You get a good job, right? So they dropped out of high school, all of them. And the result is Farlan died from liver disease related to overuse of drugs. The sister, Rogina, died from hepatitis linked to needle use. Zealan died, passed out drunk in a house fire, and Nathan blew himself up making meth. Keylin, the one who is alive, who I was able to meet again in Oklahoma where they’ve moved, he basically stayed alive because spent 13 years in the state penitentiary in Oregon. And so these stories of these people are just so moving. And Dee Knapp, the mother, is still alive at 80 and her mom died more recently at 97 years old. So you can see how the next generation has tumbled downward instead of spiraled up, which is what the futures of many Americans now are. Fifty percent of Americans now, even higher a percentage in some surveys, say that they don’t think that their next generation, their kids, are going to do as well as they are going to do. And so we have these horrible statistics that portend a dim future for the next generation. And basically, if we don’t raise strong Americans, how can we have a strong America?

SAPPENFIELD: And that’s a great segue into just talking about some of the broader themes in the book a little bit more specifically is that you raise at one point in the book, you raise the book from several decades ago, “The Other America” and the importance that had in kind of changing minds and opening thought about poverty. And you kind of say, we hope that our book can have a similar effect in opening up this world that Sheryl, you were just talking about, to people understanding how are actually people living in these circumstances and what do we need to know to change those outcomes?

KRISTOF: Yeah, there’s this fundamental disconnect because, look, the American economy now in some ways is doing great, and the stock market has been doing fantastically. And so I think people can be a little puzzled at, how can you write about so many people who are struggling at a time when unemployment is so low? And yet both are true. The overall pie has done extraordinarily well. And yet there are a lot of Americans out there with such tiny slivers that they then self-medicate ... Even during the Great Depression, life expectancy was actually increasing. Now, even though the pie is growing, life expectancy has been falling for three years in a row. And so young people in America actually approve of socialism more than of capitalism. And yet to us, the problem isn’t capitalism. It’s the way we’ve tweaked capitalism more recently. And from 1945 through the 1970s, we had a capitalist system that worked incredibly well, both to grow the pie and to slice it very equitably.

SAPPENFIELD: You’re touching on there’s a ... Chapter 5 is called “How America Went Astray.” That’s really one of the most powerful chapters I’ve read about trying to understand how we got to where we are because it’s like what is America’s greatness founded on and how can we continue that? And what would I took from that so much was this different sense of how we look at, kind of what you said, investing in human capital. From the eighteen fifties to the 1970s, America was a global leader in investing in its people. And you mentioned from the Homestead Act all the way up to really powerful examples, the GI Bill. I mean, what an investment in America’s future that was. And it was an investment in the people saying we have faith in our people to be great and we’re going to help them along the way. And I suppose in that chapter, you paint this really graphic picture and, in a good way, in a sense of really explaining why that happened. Of how we went from that vision to a different vision and how there’s a need to kind of get back to that sense of investing in our people. I grew up in the 1980s. So I’m a child of the Ronald Reagan era. And so I grew up kind of in that era where, you know, he was saying small, you know, small government. And then when Bill Clinton said, you know, the era of big government is dead. That’s the mental framework. You’re really pushing for a complete change in mental framework. Talk a little bit about that.

WUDUNN: Well, one of the biggest problems that really arose and exploded during that era, in the 1980s was this narrative of personal responsibility that sort of came along with Ronald Reagan's we don’t like the welfare queens. And so what it basically means is that you should pull yourself up by the bootstraps. And that is a saying that if you’ve ever tried to do that, I don’t think you will succeed, because, in fact, it’s impossible. In the 18th century when they used that expression in the very beginning, when they started using it, it meant to do something impossible, like you’re doing something impossible. And then over the years, somehow it’s come to mean something everybody can do. And that the idea that you should be personally responsible for everything that has to do with you, that also means that you, if you make bad decisions, it’s your fault too. Blame the victim, as though there is nothing in the environment that has anything to do with your upbringing. That is a problem. It’s true that Farlan and other people made bad decisions. They shouldn’t have dropped out of high school. They shouldn’t have started using drugs. But on the other hand, how can, in today’s day, we can predict by using the zip code a baby was born in, what the outcome of their life is most likely to be like. And so are you going to blame that infant for making bad decisions? Clearly, socioeconomic and the environmental factors play a huge role. And when a baby is born every 15 minutes exposed to opioids, drugs in their system, you can’t fault that baby. And so we really have to take a hard look at this narrative of personal responsibility and also reconsider, go back to our roots of the social contract and say, wait a second, what about, you know, collective social responsibility? We need to build our society, rebuild our society, the one that we want to live in and in a nation that is, you know, has so much injustice that’s founded on the principle of justice. We need to really get back to our roots.

KRISTOF: You mentioned some of these grand social programs like the Homestead Act. You know, as an Oregon kid growing up, we were all nurtured on the legend of our pioneer ancestors and how they crossed the country and showed this incredible courage and rugged individualism. And, you know, they would never have tried to grab for some government benefit program. And yet, you know, of course, looking back, why did the pioneers cross the country? Because of a government benefit plan. Because they knew once they got to the Willamette Valley they’d get 640 acres, and something like a quarter of white families in America owe part of their family wealth to the Homestead Acts originally. Yamhill was transformed by homesteads, later by rural electrification, and later by the GI Bill of Rights, which gave people both education and a chance to help buy their own homes. And those programs strike me as quite brilliant in that they encouraged people to take steps that would lift themselves. They were investments in the future rather than just handouts. And that made them both great investments, but also politically sustainable. And I think that we’ve lost that ethos and we’ve been too focused on pointing fingers of blame and not enough on offering helping hands.

SAPPENFIELD: One thing that I really appreciate about your book is that solutions can be a both/and thing, as opposed to an either/or. And you take pains throughout the book, appropriately to say, we’re not absolving personal responsibility here. It’s not like we’re saying that we should just absolve everyone of personal responsibility and the government should step in and make sure that all their outcomes are great no matter what they do. But again, one of those keywords that I feel from your book is balance. Is that that balance has shifted from how it was in the past when frankly, when we’re talking about when America was, you know, seemed stronger and all these things, the era that we’re talking about is when that balance was more present. And I just appreciate how in doing this you clearly are suggesting solutions and saying that balances out and we need to think more collectively about these things. But it’s also a nuanced conversation. And if we just get stuck into saying, oh, we need to expand government or we need personal responsibility, we miss that path where we can find the both/and there.

KRISTOF: That’s exactly right. That’s exactly right. You know, one of the kind of remarkable statistics we came across is that for Americans who do three things, who graduate from high school, who get a full time job, and who marry before having children, only 2% live in poverty. For people who do none of those three things, it’s about 75%. And so clearly there are behaviors that matter that we should encourage. So, you know, by all means, encourage young people to graduate from high school to take the first one. But it also turns out that it’s not just a question of haranguing people, but high schools can also do more about not kicking out troublemakers, which they historically did.

SAPPENFIELD: And you had so many people in your story where that is exactly what happened to them.

KRISTOF: Exactly. And the school got rid of a problem kid, but then society inherited somebody who would never be able to succeed on the job market. And it turns out that when states require kids to stay in school till age 18 or when they condition getting a driver’s license on being in school, that that dramatically raises high school graduation rates. And so clearly there are you know, we have to pay attention to personal responsibility. But if we’re having that conversation, we also have to have a conversation about our collective social responsibility.

SAPPENFIELD: Right. I mean, the sense that you get is that, this is a harsh truth, but that that’s OK. We’re comfortable with those. Is that really if you want to look at the actions and the priorities that we have set as a country, the real social safety net that we have invested in is prisons.

WUDUNN: I mean, I think that’s what we see, one of the most costly and biggest failures is the mass incarceration that really started with the war on drugs in the 1980s with the two acts, you know, the drug act. It was just not only a loss for the country, but also a huge injustice. I mean, we talk about, you know, this woman, Geneva Cooley, who she was addicted to drugs and she actually became a drug mule. She actually transported some drugs to Alabama, a small portion. And she was arrested. She was put in jail for 999 years without parole. I mean, this poor woman and she had been there, when I, by the time I saw her, she had already been there for like 20 years. At the same time, you have these pharmaceutical executives who were selling opioids, which got far more people addicted to drugs. And then you had the Sackler family behind one of the most prominent of these drug companies, Purdue Pharma. And none of them have been prosecuted. None of them have gone to jail. And, in fact, they have $13 billion in their war chest. And so I think that, the discrepancy is remarkable. And the prisons, yes, they’re very costly. But there are a lot of solutions coming on the front, which is very interesting. There are drug rehabilitation centers that are trying to have people diverted from prison, if they are obviously addicted to drugs, and actually diverted into treatment programs. So we visited a place in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and it’s a real role model for how it should be done. You know, drug rehabilitation takes a long time and they do have lots of rehab centers all over. Maybe you stay there for three months. You can’t cure someone in three months. This program takes 18 months to basically two years. They go through intense drug therapy, psychotherapy, they get medical treatment, and they do all sorts of things. And the recidivism rate is basically 4% after three years. I mean, they’re very successful. And it’s programs like these that other countries, peer countries, you know, in the developed world and in Western Europe and in Canada that have been used for a while. And, you know, Portugal, for instance, is a perfect example of what we in the U.S. could have done. They about the same time that we were starting, launching our war on drugs, they basically said, no, let’s actually try the public health tool kit. And so they said instead of sending these people to jail, let’s send them to drug rehab. And so now, years later, their experiment worked, ours failed. So they have dropped their overdose rate by two-thirds and they’re basically the lowest overdose rate in all of Western Europe. Whereas we, we have kept our same policies for all these years. Why aren’t we tweaking them when we see something isn’t working, and when we see over in Western Europe, a program that does a policy that does work, why can’t we be flexible enough to change? America has been known for its flexible capitalist model, but in some areas we are so rigid.

SAPPENFIELD: The book is hard reading at times, but yet the subtitle is “Americans Reaching for Hope.” And this is just another point where I probably will pause as the Monitor editor and say thank you for that, because I think certainly the Monitor would say that that’s a really important ingredient to bring to it. I was reading recently and I think this is an annual thing that you do, that you wrote a column recently in The New York Times that said this has been the best year ever. And that is an interesting, to get back to that word balance again, that I think the Monitor in particular wrestles with a lot. And I think that the careers that you have had really are exemplary. And I’d be interested for you to share how you think about that balance, in the sense that there is so much that we need to, like this book, that we need to bring to attention to be corrected, that we need to bring it and have a good conversation, informed conversation, compassionate conversation, and decide how would we as a nation, as a community, as a society, what are the values we’re going to bring to this? That we think are important to us? If you just focus on those things that are broken, you can get a really warped sense of where the world is right now. And that column was fundamentally about that, is that if you just focus on these things, you miss that we’re actually amazing problem solvers. If we actually give consent to say we can fix this, we do amazing things. Just tell me about how you’ve wrestled with that personally and professionally in terms of wanting to make sure that in Darfur or Tiananmen that you’re bringing attention, these things, but also wanting to say, folks, we can do these things.

WUDUNN: So in the book “Tightrope,” we have a chapter called “Escape Artists.”

SAPPENFIELD: Yes.

WUDUNN: Because we want to show that some of these people who came from exactly the same terrible place actually can escape. And, you know, for whatever reason, I mean, they did get nudges. They got help. In one case, one actually good friend of ours was an alcoholic. And, you know, finally he was put in jail for his umpteenth, driving under the influence. And in the end, he needed rehab, but he couldn’t pay for it. So his girlfriend married him and she had health care. And so he used her health care to get better and he did get better. He has taken that, you know, to the stars. And that’s the kind of escape artist that we see. There are many people like that. And with just other nudges as we talked about, we really can help society. We know that hope is really important. There’s been a lot of research. Right now in fact, this is one of the best times to solve problems because there are so many researchers that are creating evidence-based strategies that allow us to draw upon them and just take them to scale. But the research on hope by, you know, a Nobel laureate, Esther Duflo, she basically was doing some research in India in the developing world, and was discovering that, you know, when they gave a family a cow or an animal, not only did they make money from that particular animal, but somehow they seem to have done far better than just what you would normally get from the income stream from an animal. And it turns out what happens was that these people saw that, wow, there’s a way out. If we have this cow, we actually can, you know, sell the milk. Well, let’s try a vegetable garden and let’s sell the vegetables or let’s grow an apple tree and sell the apples. It gave them hope. And that’s what we think is the key to this. I mean, there are, so many people in the developing world who are desperately seeking to come to America because they believe in the American dream. But we see people, Americans who are floundering like the ones that we write about because they don’t have hope. And for them, the American dream is broken.