- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Behind Bernie Sanders, a passionate grassroots army – with a sting

- Harvey Weinstein, #MeToo, and the pace of social change

- France begins to reckon with the dark side of its cultural elite

- Saving India’s storks: How smelly pests became a point of pride

- From ‘radical reform’ in Finland to altered habits in Chile

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Don’t like the news? Listen for the counternarratives.

Today we look at behavior and accountability among one campaign’s backers in the presidential race and among arts-and-entertainment figures in the U.S. and in France, respect for nonhuman species, and a scan of global progress. First, a look at some quiet counternarratives.

New week, new worries? Try changing your focus.

Political potshots ring out in the United States. But hold for a moment this better-angels comment made by Elizabeth Warren at a town hall last week in Nevada: “There are a lot of good people in this government who are not political,” said the Massachusetts senator, “a lot of good people who want to get out there and do what is right.”

That can mean perspective shifts.

Utah, for example, is about as red as states come. But it just hatched a plan to cut emissions, with an eye to both local air quality (tourism) and the global climate. “It cuts across political lines,” said the state’s speaker. “[Clean air] is not a partisan issue in our state.”

A dark populism appears to color Europe. But a stadium crowd in Münster, Germany, rose en masse to protest a fan’s racist insult of a Ghanaian player from another German team, chanting “Nazis out” as the fan was removed.

Humans seem to keep driving fellow Earth species to the brink. But a sense of shared habitat may be dawning. In northern India, farmers and shepherds have fostered a negotiated coexistence with leopards, chronicling the cats’ behavior and then modifying their own in order to limit violent encounters.

Bhanu Sridharan wrote about the little-covered phenomenon for the nature website Mongabay. I asked her why that story resonated. “By and large,” she answered in an email, “people across rural India tend to accept wild animals as part of the landscape.” (See our similar solutions story below.) Scientific studies of such relationships, she noted, often focus only on the conflicts.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Behind Bernie Sanders, a passionate grassroots army – with a sting

When those with deeply held and long-deferred political beliefs finally get momentum, how can they keep their exuberance from taking on a hard edge? A report from the campaign trail.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

What makes Bernie Sanders’ supporters so passionate? They form a grassroots army unmatched by any other Democratic campaign, and have propelled the iconoclastic Vermont senator’s improbable rise to the front of the 2020 Democratic field, with a double-digit win in Nevada.

Yes, they like the idea of free college, free health care, and forgiving student debt. But it’s not just about what he can do for them; he’s encouraged them to get involved in democracy themselves – as a powerful antidote for those feeling demoralized. “I feel like he’s showing us how to fight for ourselves,” says Marie Duggan, an economics professor at Keene State College in New Hampshire.

A fraction of Sanders supporters have drawn criticism for how they wage this battle – wielding profanity and menacing threats across the increasingly coarse Twitterverse, where Senator Sanders has more followers than his four top rivals combined. “There’s a lot of slander of Bernie supporters by people who seem outraged by our passion,” tweeted one supporter advocating “Medicare for All” after losing her mother and watching her dad fall into financial ruin. “Do they ever stop to ask ‘Why are these people so energized?’”

Behind Bernie Sanders, a passionate grassroots army – with a sting

The supporters who have propelled Bernie Sanders to the front of the Democratic field range from septuagenarian social justice warriors to millennials saddled with student debt. But they share this: The iconoclastic senator from Vermont has awakened in them a sense of empowerment, at a time when liberals have been feeling particularly demoralized. Many put it in Kennedyesque terms, saying it isn’t just about what he can do for them – it’s about what they can do for their democracy.

“He’s asking us to create a popular movement that will be strong enough to change the system and make it works for us,” says Marie Duggan, an economics professor at Keene State College in New Hampshire. “I feel like he’s showing us how to fight for ourselves.”

In his most resounding show of force yet, Mr. Sanders won the Nevada caucuses over the weekend by more than 25 points, finishing far ahead of his closest rival, former Vice President Joe Biden.

That win was powered by a grassroots army of passionate fans who host “Bern Baby Bern” disco parties and bake cookies featuring the senator’s unruly white hair in frosting. Despite many having very limited budgets, they respond, over and over, to the Sanders campaign’s relentless requests to donate, collectively giving him nearly $75 million in small donations – by far the most of any Democratic campaign.

And they enthusiastically advance his cause on social media, where Mr. Sanders commands a Twitter following of 10.6 million – more than that of his four top rivals combined. The disproportionately young and digitally savvy cadre of supporters has been instrumental to the improbable rise of a democratic socialist, whose digital game dwarfs that of his Democratic rivals and has inspired many to get involved in politics for the first time.

At the same time, there’s a darker side to some of this enthusiasm. Some Sanders devotees have sparked concern within the Democratic tent for vitriolic and even menacing rhetoric toward political opponents, raising questions about the extent to which Mr. Sanders should be held accountable for all his supporters’ behavior.

While the senator has repeatedly condemned any harassment or violence in his name, his campaign – like the Trump campaign in 2016 – faces a particular challenge as it’s bringing in people who feel disenfranchised and tend to distrust the system, says Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino.

“His campaign is in a unique position to inspire people who would not otherwise be involved in politics,” says Professor Levin. And although that’s clearly a positive thing, some of his supporters also tend to operate from an anti-institutional framework – and may be willing to go to extreme lengths to achieve their goals. “We have to beware of the ‘any means necessary’ people,” he says.

“I’m one of the Bros”

Shelby Parham, a young Latina administrative assistant in Chicago, writes in her Twitter bio: “I like Bernie… I’m one of the Bros.”

That’s a reference to a pejorative term coined during the 2016 campaign for Mr. Sanders’ passionate and at times combative online army. Ms. Parham sees the term in a different light.

“The media tries to paint Bernie supporters as the left-wing Trump supporters – as being aggressive, mean Twitter hacks who just can’t leave people alone or respect other people’s decisions,” says Ms. Parham. “But ... to me, a Bernie Bro is a die-hard supporter that will be the ones to go knocking on doors. We’re the ones who have been with him and will stay with him.”

Before work, after work, and whenever she has a break at work, she pulls out her phone to tweet or retweet pro-Bernie material. Sometimes when she really “indulges,” she says, laughing, she will retweet as often as 30 times an hour.

Other Sanders supporters wield four-letter words far more frequently against his critics, sometimes with threatening undertones.

David Klion, a journalist in Brooklyn with nearly 60,000 Twitter followers, created a firestorm when he tweeted on Feb. 13: “Libs who are flirting with Bloomberg now should be aware that they are going on lists. Next time they pretend to care about racism or sexual harassment or really anything other than money and power, we will remember what they were doing right now and we will remind everyone.”

After the Culinary Workers Union of Nevada warned its 60,000 members in a flyer that they could lose their hard-won health care insurance under Sanders’ “Medicare for All” policy, self-proclaimed Bernie supporters unleashed a barrage of attacks against two union leaders, both minority women.

“This is your chance to fix your mistake before the millions and millions of Bernie Sanders supporters will find you and end your ability to earn a living,” said one email obtained by the Nevada Independent, calling the women “corrupt [expletive]s” and “fascist imbeciles.”

When questioned by Pete Buttigieg at last week’s Las Vegas debate over the issue, Mr. Sanders said that out of his 10.6 million Twitter followers, “99.9% of them are decent human beings, are working people, are people who believe in justice, compassion, and love. And if there are a few people who make ugly remarks, who attack trade union leaders, I disown those people. They are not part of our movement.”

In the hours after the debate, a Monitor analysis of responses to pinned tweets from Mr. Buttigieg and Michael Bloomberg found that the vast majority of negative responses came from pro-Sanders accounts.

Mr. Sanders also intimated that perhaps Russian trolls were to blame. Two days later, The Washington Post reported that U.S. officials told Mr. Sanders that Russia was seeking to boost his campaign. But even if Russian actors are seeking to exploit divides within the Democratic electorate, in keeping with their aim of sowing discord in American democracy, at least some of the most prominent antagonists are high-profile Sanders surrogates and verified Twitter users who are very much American.

And, to a certain extent, that’s not surprising given that Mr. Sanders is drawing from the most progressive flank of the party – or even outside the party’s traditional bounds.

“What you end up getting when you’re sampling from the fringes is you end up with the people who are more interested in radical change,” says University of Maryland sociologist Dana R. Fisher, whose recent book “American Resistance” looks at how left-leaning activism has grown since Donald Trump took office. But, she adds, “I don’t think [Mr. Sanders] is cultivating it at all.”

Sanders supporters say they, too, have been subjected to vicious attacks, and deny the premise that their camp disproportionately displays offensive online behavior. Many describe the “Bernie Bro” narrative as deliberately seeded by their detractors – first by the Clinton campaign in the 2016 cycle, and now others within the Democratic Party.

“We recognize that our opponents in the establishment would like to perpetuate a false myth to discount the breadth and diversity of our supporters – and we categorically reject it,” says Sarah Ford, deputy communications director for the Sanders campaign. “As the senator has said loudly and clearly, there is no room in the political revolution for abuse and harassment online, and we must live our values of love and compassion.”

“It definitely radicalized me”

Sanders rallies are the political version of a rock concert, only the star has shaggy white hair and glasses. The senator did make an album once, in 1987, but when singing “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” he sounded pretty much the same way he does when shouting his political demands – hunched over, gripping the mic with his left hand and waving his right.

Somehow, in an era when older white males are not cool, he always brings down the house. Before mothers holding babies in slings across their chests, and students waving his face on sticks, before upscale women in fancy coats and scruffy men in ripped jeans, he barks out his call for free health care, free college, and equal pay for women. People whoop and pound the floor with their feet in rapid succession, until the din of democracy spills out into the silent streets of small towns across America.

Sanders supporters aren’t “angry just for being angry,” says David Robin, co-founder of New York City for Bernie Sanders 2020, and a digital strategist who does social media work for a number of progressive politicians and causes. “They’ve been screwed over by the system.”

Mr. Robin, who grew up in a lower-middle-class family and was assured by his high school counselor that there was no need to worry about taking out loans for college because he’d pay them back once he started working, graduated in 2009 at the height of the financial crisis with $40,000 in debt. The job market was tight, so he went back to school in hopes that getting an extra degree and giving the economy a couple years to bounce back would make it easier to find work.

He came away with a master’s degree in sociology and $137,000 in debt – driving him to join the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011, his first foray into political activism. He says he’s paid income-adjusted installments on his loans consistently, but isn’t even keeping up with interest. He now owes $175,000.

“I’m just throwing money at this and it’s just getting worse and worse,” he says, citing a Brookings Institution report that estimated student loan default rates could reach 40% by 2023. “It definitely radicalized me.”

He shared his experience via #MyBernieStory, a collection of short videos and tweets in which supporters explain what drew them to Mr. Sanders – someone who they say actually understands and cares about their struggles.

“There’s a lot of slander of Bernie supporters by people who seem outraged by our passion,” writes Lizzy Vivino in another #MyBernieStory thread. “Do they ever stop to ask ‘Why are these people so energized?’”

Harvey Weinstein, #MeToo, and the pace of social change

A very public reckoning today for Harvey Weinstein will likely ripple through private lives as well, as it prompts new discourse about how existing laws on sexual harassment and assault – often ignored – are interpreted and applied.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Stacy Teicher Khadaroo Staff writer

The conviction of Harvey Weinstein on two counts of felony sex crimes on Monday marks a shift in the way U.S. society has responded to women’s stories of harassment and sexual assault.

The two-year saga of Mr. Weinstein’s downfall has ushered in a new era of public accountability. One of the most significant of these changes is what Selina Gallo-Cruz, professor in the women’s studies program at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, calls a “public restaging” of women’s sexual harassment. “What has long been commonplace in the private, backstage experiences of women’s lives is now being negotiated on a public, front stage,” she says.

Still, many scholars caution that even with concrete changes happening in workplaces and legislatures across American society, it remains to be seen how deep and how lasting they may be.

For Claire Wofford, professor of political science at College of Charleston in South Carolina, the societal movement seen already calls for cautious optimism. “We should consider this not a time of celebration, but certainly a time for hope.”

Harvey Weinstein, #MeToo, and the pace of social change

State Rep. Allison Nutting-Wong says she has witnessed a lot of progress in American society since the #MeToo movement sent a jolt through the decadeslong battle against sexual harassment.

A new mother, the New Hampshire Democrat recently succeeded in getting the House to pass a bill addressing online harassment – part of a wave of legislation passed in other states as well. “Only a few years ago, a similar idea had a lot of opposition,” Representative Nutting-Wong says. “This year when no one noticed, it went through – that says a lot about what has changed in the past few years.”

Yet even as she and many others witnessed two guilty verdicts in the trial of Harvey Weinstein on Monday, Representative Nutting-Wong was reminded just last week how subtle and pervasive a culture of workplace harassment can be.

On the very day the New Hampshire House voted to reprimand seven lawmakers for not completing mandatory anti-harassment training, she had an uncomfortable encounter with a group of older male colleagues at the State House.

“I got on the elevator at the first floor, and there are already a handful of guys in there,” she says. “And they’re just like, ‘Oh, come in – we don’t bite.’” But then another in the elevator guffawed, ‘No, we just nibble,’“ Representative Nutting-Wong says, noting that she tweeted about the incident later that day.

She didn’t feel her colleagues were intentionally trying to make her feel uncomfortable, she says, nor did the crude comments reach a level, in her view, that would demand a formal complaint. Still, she got off the elevator before she reached her floor, and the encounter reaffirmed to her, almost ironically, how important the mandatory training is, she says.

Just as with the conviction of Mr. Weinstein, who was found guilty of two felony sex crimes but acquitted of the most serious charges, many women and men across the country see a similar mix of progress in public accountability – as well as the same-olds of the status quo.

Indeed, the two-year saga of Mr. Weinstein’s downfall has played out like a civic morality tale since his case became the first to rally women to the cause of #MeToo. As a major Democratic donor and a producer whose films are still considered among the greatest of their eras, the Hollywood kingmaker came to embody the looming and intimidating presence often perceived as a defining marker of male power and the privileges it commands, experts say.

Mr. Weinstein’s conviction symbolizes a public recompense after the collective courage of women broke through the silence of the commonplace.

“Since the Harvey Weinstein case came on the scene, we have definitely seen changes in how our institutions and organizations respond to, and prepare for, issues of sexual harassment,” says Terri Boyer, founding director of the Anne Welsh McNulty Institute for Women’s Leadership at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. “And while we have long had laws and policies on the books which prohibit harassment, you are finally seeing companies and institutions’ willingness to follow through with them, and even take on their own leadership in some instances.”

A taboo broken

More women across the country, too, have felt empowered to raise formal complaints of sexual harassment in the workplace, according to the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission – which has seen overall complaints from other areas in the workplace decline, in fact.

“This is happening not just in Hollywood, but in other media conglomerates, government and politics, education, and corporations,” Ms. Boyer says about the growing number of women continuing to speak out. “As a social scientist, this indicates to me that we are actually seeing the beginnings of cultural change.”

One of the most significant of these changes is what Selina Gallo-Cruz, professor in the women’s studies program at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, calls a “public restaging” of women’s sexual harassment. “What has long been commonplace in the private, backstage experiences of women’s lives is now being negotiated on a public, front stage,” she says.

“I try to impress upon my students what life was like as a young woman when it was common to witness and experience sexual harassment,” Professor Gallo-Cruz says. “But just as it was ‘normal,’ it also existed in a private sphere.”

“What was taboo was not the harassment itself but speaking out about it in public,” she continues. “Now the times are changing this dynamic – we are in the midst of a paradigm shift.”

Indeed, this shift has been reflected in some of the laws state legislatures have passed in response to the number of women willing to make their experiences public, observers say.

“If you look at the case law and the attitudes before #MeToo, everyone thought that secrecy was fine,” says Elizabeth Tippett, professor at the University of Oregon School of Law in Eugene. “If there was a complaint about harassment, for instance, and an employer asked you to keep it secret once it was settled, it was considered reasonable, viewed as part of the transaction.”

“There was not much thought about what the public cost of secrecy might be or how that might affect other people who are in the same position,” she says, noting how some states have moved to limit certain kinds of nondisclosure agreements.

“A time for hope”

Still, many scholars caution that even with such concrete changes happening across American society, it remains to be seen how deep and how lasting they may be. After all, from business and industry to culture, media, and politics, the country’s halls of power remain overwhelmingly male.

“The primary problem with sexual assault and harassment hasn’t been the lack of laws prohibiting that type of behavior. It’s been about how those laws have been interpreted, applied, and, all too often, ignored,” says Claire Wofford, professor of political science at College of Charleston in South Carolina. “Laws never operate in a cultural vacuum, and their potency is directly shaped by the underlying values of the society.”

Representative Nutting-Wong in New Hampshire notes how the responses to her tweet last week have ranged. Some criticized her as a “snowflake” unable to handle the rough-and-tumble competitive world of politics, while others have castigated her decision not to lodge a formal complaint against her colleagues. Those disparate reactions underscore a classic Catch-22 that many women often feel in uncomfortable workplace situations.

“To me, the real benefit of the #MeToo movement and the public reckoning over men like Harvey Weinstein and Matt Lauer is that the larger culture is starting to recognize just how embedded sexism and sexual violence are in our society, and how the power structure has operated to protect men and damage women – and some men,” says Professor Wofford.

“It is when you get that larger kind of cultural shift in values that laws that prohibit certain types of behavior can actually begin to operate,” she continues. “We should consider this not a time of celebration, but certainly a time for hope.”

France begins to reckon with the dark side of its cultural elite

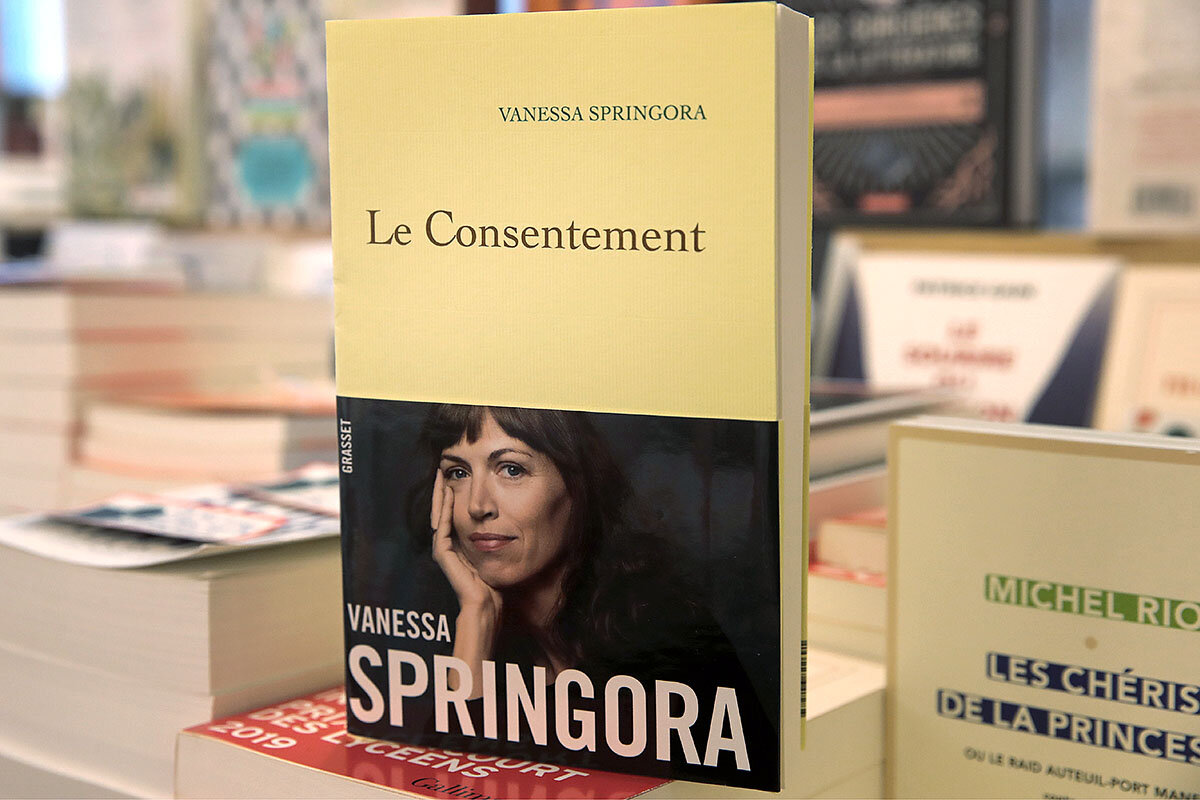

This next piece explores another social reckoning. Few countries elevate artists and intellectuals as much as France. At times, that esteem has appeared blind to critical faults. Our writer explores why that is – and why that’s changing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

For decades, being a member of France’s intellectual and cultural elite has meant not just adoration by the public, but also a special set of rules to live by. Sometimes that tolerance has extended to questionable, possibly criminal activity, like that of author Gabriel Matzneff’s writing about having sex with minors.

But that appears to be changing. In the era of #MeToo, France has begun giving more credence to women’s and victims’ voices. In the past several weeks figures like Mr. Matzneff have come under fierce public criticism.

The French intellectual elite have enjoyed a special place in society since the days of the French Revolution, when their subversive ideas, opposition to political culture, and fight for freedom of expression were lauded. Literary figures in particular have been celebrated for their free thinking and progressive ideology.

More recently, however, defending womanizers or illegal sexual behavior has become increasingly gauche.

“There [was] this idea that the literary world is autonomous from the rest of the world, where rules and morals are applied differently and people can get away with anything,” says sociologist Pierre Verdrager. “But now, everyone wants to be on the right side of history.”

France begins to reckon with the dark side of its cultural elite

For decades, the intellectual elite of France, including its writers, cinema directors, painters, and other cultural nobility, have enjoyed public adulation beyond that of their peers in other Western societies. And along with that status has come a separate moral code.

Sometimes that just means they are afforded a greater tolerance for eccentricity or minor vice. But at others, it has meant that their sometimes questionable – and occasionally even criminal – acts are defended and often pardoned.

Take French writer Gabriel Matzneff, who has received numerous national literary awards – even when some of his work revolved around his own sexual involvement with minors. Or French Polish film director Roman Polanski, who has been embraced for years, while continuing to produce award-winning films, despite U.S. attempts to bring him to justice after he fled his conviction for a 1973 sex crime.

But since the Harvey Weinstein scandal and subsequent #MeToo movement, France – like many countries around the world – has begun giving more credence to women’s and victims’ voices. And just the past several weeks have seen Mr. Polanski and Mr. Matzneff come under fierce public criticism for their histories.

The backlash is telltale of a twofold cultural shift. It highlights a willingness to allow more space for women to be heard not just within the literary world but also more generally in society, as well as an end to an era when France’s intellectual elite – who are usually men – are forgiven their bad behavior in the name of art or rebellion.

“It’s not so much that intellectuals were pardoned for everything they did as it’s that we’re witnessing a change in social rules and morals in society more generally,” says Violaine Roussel, a professor of sociology at the University of Paris 8, “and that has struck out at public figures first.”

“Where rules and morals are applied differently”

The French intellectual elite have enjoyed a special place in society since the days of the French Revolution, when their subversive ideas, opposition to political culture, and fight for freedom of expression were lauded, and credited by some for sparking the revolution itself.

By the time May 1968 rolled around – when student protests led to nationwide strikes and civil unrest – the French had already long relied on their intellectual class to provide moral guidance on political and social issues.

Literary figures in particular, such as Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, or Victor Hugo, were celebrated for their free thinking and progressive ideology; Baudelaire and Flaubert revered for their stories of libertine lifestyles.

It’s in this context that Mr. Matzneff was able to write extensively and with impunity about his sexual relationships with teenage girls and boys ages 8 to 14 in the Philippines. Throughout his career, he has received numerous French literary awards, and his accounts of sexual encounters with young girls during a memorable 1990 television program ruffled few feathers.

But that changed with the publication of “Le Consentement” (“Consent”) in January by editor Vanessa Springora, which details her relationship as a teenager with the much older Mr. Matzneff. Since then, France’s publishing world – and society more generally – has been thrown into a tailspin.

Mr. Matzneff has gone into hiding in Italy, with his trial for child abuse offenses in France set for 2021. In mid-February, French police raided his publisher Gallimard in search of possible censored texts. The French government has launched an appeal to any woman who was abused by Mr. Matzneff to come forward.

Just seven years ago, in 2013, when sociologist Pierre Verdrager published “L’Enfant Interdit: Comment la pédophilie est devenue scandaleuse” (“The Prohibited Child: How Pedophilia Became Scandalous”), it made few waves and received little celebrity. Now, the scandal around Mr. Matzneff has catapulted it into the public eye for its dissection of pedophilia.

“My book is symptomatic of what is going on,” says Mr. Verdrager. “When I was first looking for a publisher, everyone told me it would never sell. ... But now, I am a mirror of how things have changed.”

Since #MeToo and France’s comparable #Balancetonporc movement, defending womanizers or illegal sexual behavior has become increasingly gauche.

“There [was] this idea that the literary world is autonomous from the rest of the world, where rules and morals are applied differently and people can get away with anything,” Mr. Verdrager says. “But now, everyone wants to be on the right side of history.”

That’s meant an end to the relatively comfortable existence for figures like Mr. Polanski, who pleaded guilty to unlawful sexual intercourse with a 13-year-old girl in California in 1977.

Feminist groups have promised to protest at the César Awards, France’s equivalent of the Oscars, on Feb. 28 after Mr. Polanski’s latest film, “J’Accuse,” was nominated for 12 awards. And in mid-February, the entire board of the Césars resigned, against the backdrop of, among other things, the ongoing Polanski controversy.

Impunity’s fall, feminism’s rise

Even if the changing attitudes toward France’s intellectual elite can be felt across swaths of society, nowhere has the transformation been quicker than in its literary sphere. “Before, books about women were always on the margins, people made fun of them a little bit,” says Sandra Monroy, an editorial manager at First Editions publishing house in Paris. “Now, women’s voices in general are finally being taken seriously.”

For decades, female authors were relegated to littérature féminine – women’s literature – a concept seen by many as pejorative. While French feminists like Simone de Beauvoir and Hélène Cixous have made significant contributions to women’s literary gains, feminism as a concept has only entered the landscape in recent years.

First Editions, which puts out the French version of the “For Dummies” (“Pour les Nuls”) manuals as well as books on literature, poetry, and cinema, didn’t have literature on feminism when Ms. Monroy started in 2015.

“Shortly after I arrived, I suggested creating practical manuals or other books on feminism,” she says. “That idea was quickly brushed off. At the time, it was also taboo to talk about the relationship between a female book editor and a male writer,” like Ms. Springora’s relationship with Mr. Matzneff.

Since then, she says, writing on feminism has taken off in France. Nonexistent just three or four years ago, sections of bookstores have since been dedicated to the topic, and publishing houses are jumping on the phenomenon.

Mr. Matzneff’s fall from grace and the subsequent effects on French society are perhaps most notable in the fact that dissent against Ms. Springora’s book or denial of Mr. Matzneff’s behavior is relatively absent from mainstream discourse.

“It’s true, without a doubt, that ‘star status’ is not what it used to be,” says Ms. Roussel, the sociologist. “This has contributed to no longer seeing these figures as sacred as they once were.”

Difference-maker

Saving India’s storks: How smelly pests became a point of pride

We’re not done with the topic of interspecies understanding for today. In another Indian village, here’s another shift in, yes, how another nonhuman animal is perceived.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Arundhati Nath Contributor

How do you save an endangered bird?

Maybe by thinking outside the box. For Purnima Devi Barman, an Indian conservationist, the mission to protect greater adjutant storks has involved cooking competitions, hand-woven dresses, and even baby showers for the birds.

There are no more than 1,200 mature storks left in the world, most of them here in Assam state. But the huge, plain-looking scavengers are often viewed as smelly pests. As their wetland habitats disappear, they often move into trees in villagers’ backyards, where they’re far from welcome.

“Most people worked with charismatic species like the rhino or the elephant,” Dr. Barman says, “but the [stork] needed to be conserved, too.”

Doing so, she realized, would literally take a village. People weren’t aware of the stork’s ecological significance, she realized, but she needed to do more than give information. She needed to involve residents in the process, and make the bird a symbol of pride.

Today, hundreds of women are part of her “hargila army,” so called because of the stork’s name in the Assamese language: Hargila means “bone swallower.” The villagers rehabilitate injured storks, and create stork motifs in fabrics and garments they sell, and celebrate storks hatching.

Saving India’s storks: How smelly pests became a point of pride

Dressed in bluejeans and a gray top, Purnima Devi Barman carefully balances her feet as she clambers down from the 80-foot-high bamboo platform.

She’s been looking for greater adjutant storks: huge, plain-looking scavengers named for their stiff-legged, almost military gait. For years, the greater adjutants built their nests in tall trees fringing the shallow waters in uninhabited wetlands across Assam, one of their last habitats.

But early in her career as a conservationist, Dr. Barman noticed a change.

“When I started research with these storks for my Ph.D. program, I spotted very few storks compared to the large numbers I had seen as a child, growing up in rural Assam,” Dr. Barman says, recalling how her grandmother told her stories about different species and taught her how to identify them. Indeed, the stork is now endangered, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, with only 800 to 1,200 mature birds left in the world – most of them in Assam.

The birds’ wetlands are fast disappearing, replaced by buildings, roads, and cellphone towers as the region quickly urbanizes. That means the storks are forced to look for trees next to the homes of villagers, where they’re often far from welcome.

Hargilas, they are called in Assamese: “bone swallowers.” Many residents here in the villages of Dadara and Pacharia object to the rotting flesh hargilas eat, and their smelly droppings soiling gardens. They see the birds as such a bad omen that they are even willing to chop down magnificent old trees in their backyards to get rid of the nests. Dr. Barman once saw nine baby birds fall to the ground when a villager chopped down a tree with many nesting storks.

“I delayed my Ph.D.,” she says, “and focused more on keeping the bird alive in its habitat. Most people worked with charismatic species like the rhino or the elephant, but the hargila needed to be conserved, too.”

And one of the most important tools to do that, she discovered, was shifting attitudes toward the storks – one stork baby shower, dress, or prayer at a time.

Protecting a “pest”

Back in 2007, when Dr. Barman tried to stop a villager from cutting down storks’ trees, she was taken aback by his anger. Others laughed when she told them that the greater adjutant was endangered and needed to be conserved.

“I realized that it wasn’t the people’s fault. They were completely unaware about the ecological significance of the endangered stork,” Dr. Barman says. She recognized that to raise awareness, she needed to involve residents in the conservation process and make the bird a symbol of pride.

Shortly afterward, Dr. Barman mobilized a large number of women from the village and spoke to them about the importance of these birds and their dwindling population. She organized drawing competitions among the children, and cooking competitions, where the women would prepare the traditional Assamese rice cakes or pithas, and round-shaped laddoos, or sweets.

The “hargila army,” she called the volunteers. Dr. Barman became known as “hargila baideu,” or stork sister. More than 400 women are members of the hargila army, and 200 are actively involved in the conservation process today. They help rehabilitate injured storks that fall off their nests, boost awareness, and create motifs of hargilas in traditional Assamese hand-woven gamosa towels and mekhela sador dresses, which are often sold to tourists.

“I have been a member of hargila army since 2007,” says Sangeeta Das, a friendly woman from Dadara. “Initially we thought that the hargila was a dirty bird because it ate dead fish and dirtied the backyards. ... However, when Purnima baideu explained to us about the importance of this bird, we realized how endangered this bird is and that we need to conserve it. Eventually it became a symbol of pride for us.”

Today, Dr. Barman is a project manager at the Indian nonprofit Aaranyak, coordinating its community conservation initiative. She has tried to make the hargila army’s women financially independent by providing them with looms and thread to weave. The local district administration and the police have also supported her project, providing transport, looms, and nets to catch fallen birds. “I believe women’s empowerment is very important to make them a part of the conservation efforts. Also, I had to develop a strong bond of friendship with the women to make them aware and sensitize them,” says Dr. Barman.

Prayers for storks

Her efforts are beginning to bear fruit. The hargilas are now finding a place in poems and songs sung during prayer meetings in the community prayer halls. A statue of the hargila has been made and displayed in the village. And during the breeding season, women even conduct a panchamrit ceremony for the birds – traditionally done to fete an expectant mother.

“Panchamrit is a mix of five ingredients: cow’s milk, yogurt, honey, sugar, and clarified butter. There are celebrations, prayers, and merrymaking,” explains Mamoni Malakar, a hargila army member. “After the baby birds are born, a baby shower is also organized in the temples or community halls. A cake is cut, the women discuss and spread awareness about the bird in the village, and there are prayers offered for the well-being of the birds.”

Now, the wide-wing-spanned birds are regularly seen perched on tall trees and high up in the skies of Dadara. Since 2007, Dr. Barman says, the number of hargila nests in these villages has risen from just 28 to more than 200.

“Purnima has given a completely new dimension to the conservation process by making the entire community interested and involved,” says Parimal Chandra Bhattacharjee, trustee and vice chairman of the Wildlife Trust of India and retired head of the department of zoology at Gauhati University. “It wouldn’t be possible to protect the endangered hargila without the society’s involvement.”

The conservationist has received several awards, including the Whitley Award, known as the “Green Oscars.” She is also a recipient of the India Biodiversity Award from the United Nations Development Program and the Nari Shakti Puraskar, India’s highest civilian honor for women.

However, Dr. Barman knows that her task is far from over. “I want to work on the conservation of the hargila forever,” she says. “A lot more needs to be done and this is a difficult, continuous process.”

Points of Progress

From ‘radical reform’ in Finland to altered habits in Chile

When the Monitor first set out to track episodes of credible progress with this franchise, some editors wondered about its sustainability. Gratefully, worthy stories have kept flowing. Today’s set will take you from Maryland (commemorating black history) to Malawi (protecting elections), and beyond.

From ‘radical reform’ in Finland to altered habits in Chile

1. Maryland

Maryland unveiled life-size bronze statues of abolitionists Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass during a Feb. 10 ceremony at its State House. Both Tubman and Douglass hail from Maryland’s Eastern Shore, and the statues’ dedication comes as the state attempts to better commemorate its black history – by replacing or removing monuments for supporters of slavery. “A mark of true greatness is shining light on a system of oppression and having the courage to change it,” says Adrienne Jones, the state’s first black and first female House speaker. “The statues are a reminder that our laws aren’t always right or just. But there’s always room for improvement.” (The Associated Press)

2. United States

For the first time in four years, life expectancy increased in the United States, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which gathered data from 2018. The rise – only a month – is largely a product of lower mortality rates for drug overdoses and cancer. It also ends a three-year period of stable or decreasing life expectancy in the U.S., following decades of a steady rise. Drug overdose deaths fell for the first time in 28 years in 2018. While deaths caused by some overdoses, from such drugs as heroin and painkillers, declined, those from other drugs – namely fentanyl, cocaine, and methamphetamine – increased, leading experts to say that the drug problem in the U.S. is still a crisis. (The Associated Press, The Hill)

3. Chile

Chile’s toughest-in-the-world restrictions on sugary drinks have helped reduce their sale by almost 24% in two years, according to researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The country’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising, first enforced in 2016, bans the sale of sugary drinks in schools, attaches stark black-and-white labels to products considered unhealthy, and restricts marketing of junk food to children. When the law took effect, Chile was the world’s leading consumer of sugary drinks, and its population still struggles with obesity. Chile’s efforts have had a ripple effect reaching a dozen other countries, which have introduced new labeling policies for food and drink packages, experts say. (The Guardian)

4. Finland

In an effort to promote gender equality, Finland will give new fathers and mothers the same amount of paid time off from work. Called a “radical reform” by Minister of Health and Social Affairs Aino-Kaisa Pekonen, the move extends paid paternity leave to seven months, which is equal to maternity leave. The extension is intended to encourage more men to participate in domestic life and child rearing to help boost the country’s declining birthrate. Finland’s five-party coalition government – led almost completely by young women – managed to pass the reform, whereas a previous government labeled it too costly in 2018. (Reuters)

5. Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan made “major progress” in reducing involuntary labor in its cotton picking industry last year, reaching 94% voluntary participation, according to a United Nations report. At just over 100,000, the number of involuntary workers marks a near-40% decrease from the year before. Meanwhile, workers reported higher wages and better conditions, as the government enforces new legislation criminalizing forced labor. Uzbekistan is one of the world’s leading cotton exporters, with about 1 in 8 adults participating in its harvest last year. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

6. Malawi

For the second time in history, an African court has declared an election void due to apparent attempts to rig the vote. After the state electoral commission received nearly 150 reports of “irregularities” during the country’s presidential election last May, Malawi’s constitutional court ordered another vote within 150 days. The ruling follows petitioning from opposition parties and widespread protest from citizens – many of whom hope that the ruling will force political parties to compete on their own merit. More broadly, experts hope that the decision – coming three years after Kenya’s nullified presidential election in 2017 – signals a trend toward freer and fairer elections across the continent. (The Economist)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Antidote to coronavirus fears: Trust in leaders

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

With reports of more outbreaks beyond China, leaders in many countries are desperate to keep or restore trust in order to cope with both the virus and the viral fear that has come with it. The range of responses puts a favorable spotlight on those governments that already had built up competent health systems and honest communications to meet such a challenge.

In general, examples of trusted leadership are getting harder to find, according to the latest “Trust Barometer” from communications firm Edelman. In its latest survey of 28 countries, it found two-thirds of people do not have confidence that “our current leaders will be able to successfully address our country’s challenges.” Edelman recommends all leaders try to be ethical as they also try to be competent in solving problems.

Trust in leaders and their expertise to handle a health crisis is an essential “vaccine” in controlling public fears. Governments need the traits of trust – integrity, transparency, accountability, and compassion – long before a crisis strikes. Or, as China and other countries are finding, they must scramble to build up trust. As they do, fears will lessen and help end this global outbreak.

Antidote to coronavirus fears: Trust in leaders

In South Korea, the first democracy to cope with a massive outbreak of the coronavirus, President Moon Jae-in is scrambling to be seen as a trusted leader against harsh public criticism of his response. “This is an unusual emergency situation,” Mr. Moon had to explain Monday. “Instead of limiting our imagination with regard to policy, we have to make bold decisions and implement them quickly.”

In Singapore, by contrast, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has largely kept the trust of citizens in his highly centralized island state. The government, for example, helped prevent panic on social media by setting up its own WeChat platform to provide accurate information. By being transparent and instructive, it maintained credibility.

Meanwhile in China, health officials admitted Friday they had created mistrust by constantly altering the “criteria” for what is a “confirmed case” of the virus. The confession may have been an attempt to regain trust and, with it, public cooperation.

With reports of more outbreaks beyond China, leaders in many countries are desperate to keep or restore trust in order to cope with both the virus and the viral fear that has come with it. The range of responses puts a favorable spotlight on those governments that already had built up competent health systems and honest communications to meet such a challenge.

In general, examples of trusted leadership are getting harder to find, according to the latest “Trust Barometer” from communications firm Edelman.

In its latest survey of 28 countries, it found two-thirds of people do not have confidence that “our current leaders will be able to successfully address our country’s challenges.” A similar number “worry technology will make it impossible to know if what people are seeing or hearing is real.” And 57% said news media is “contaminated with untrustworthy information.”

Edelman recommends all leaders try to be ethical as they also try to be competent in solving problems. Government, for example, must reduce partisanship, address problems at the community level, and partner with the private sector. Trust “is no longer only a matter of what you do – it’s also how you do it,” the report states.

Trust in leaders and their expertise to handle a health crisis is an essential “vaccine” in controlling public fears. Governments need the traits of trust – integrity, transparency, accountability, and compassion – long before a crisis hits. Or, as China and other countries are finding, they must scramble to build up trust. As they do, fears will lessen and help end this global outbreak.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A healing response to extremism

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Allison J. Rose-Sonnesyn

The hatred, anger, and fear that fuel extremism can seem unstoppable. But as a community experienced when the threat of a violent demonstration loomed, there’s something more powerful: God’s limitless love, which brings healing peace to light.

A healing response to extremism

Reading the news, scrolling through social media, or talking with friends and family, it’s clear there’s a concern that extremism, hatred, resentment, revenge, and fear are inevitable and unstoppable. But if we look deeper, is it possible to find something more compelling and more powerful than these sentiments and their negative influence?

Through my study of Christian Science, I’ve found that there is something more powerful. It’s divine Love. This Love is God, and it is the most powerful force there is. It’s all-encompassing. There is no extremism in this Love. There’s no conditionality, fickleness, or false hope about it. It’s infinite good. Its strength and protecting power are perfectly balanced with its gentleness, tenderness, and peace.

The mission of Christ Jesus was to tell about and show us this Love. During a time of political and religious extremism, Jesus showed that our relation to God, Love, is like that of a parent and child. God is our heavenly Father-Mother, and we – all of us – are created in divine Love’s spiritual likeness. Divine Love could never subject us to anything unloving, including illness, fear, or hate.

This spiritual reality underlies the inherent ability we each have to express the balance of divine Love in all we do and say and to experience the healing God’s love brings to us and to those around us, countering extremist or hateful thoughts and acts.

About a year and a half ago, a large white supremacist demonstration was scheduled to begin on a Sunday morning less than two blocks from the Church of Christ, Scientist, I attend. A counter demonstration was being organized to confront this group. Law enforcement anticipated violence between the two groups.

Along with other members of the extensive faith community in our city, my church resolved to address this situation in the spirit of Christ. We decided to hold our Sunday service as normal that morning, and prayed to recognize divine Love’s power to counteract and prevent acts of hatred and violence. We also resolved that if anyone came into the church, they would only be met with love and Christly compassion.

The Bible Lesson that morning spoke to the power of divine Love, which expresses itself throughout all creation. For instance: “This then is the message which we have heard of him, and declare unto you, that God is light, and in him is no darkness at all” (I John 1:5), and “This is his commandment, That we should believe on the name of his Son Jesus Christ, and love one another, as he gave us commandment” (I John 3:23).

Peace, joy, and love permeated the service. Though we were all aware of the prognosis for the situation, there was never an expression of fear.

Following the service, we found out that the hundreds of white supremacists who were expected to demonstrate didn’t materialize. The few who did come left within minutes. There was no violence, and the entire situation was defused before it began. Many in our church and beyond saw this as evidence of the power of divine Love.

Jesus said, “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:44, 45).

Jesus himself lived this, with healing effect. For instance, when people were so filled with jealousy, hatred, and resentment that they wanted to push him off a cliff, Jesus’ understanding of the all-power of God’s love enabled him to walk through the angry mob to safety. He left his example so that we, too, could prove the power of divine Love.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, was a follower of Christ Jesus and experienced the healing power of divine Love in her life. In her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” she points to the power of divine Love to dissolve “error,” or that which is unlike Love: “In patient obedience to a patient God, let us labor to dissolve with the universal solvent of Love the adamant of error, – self-will, self-justification, and self-love, – which wars against spirituality and is the law of sin and death” (p. 242).

It is possible to know and feel the Love that is God, which counters extremist tendencies, bringing to light peace, love, and joy.

A message of love

A subdued Carnival

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. You can look at the U.S. president’s moves on the intelligence community as a hollowing out, or as a consolidation. Either way, there will be consequences. We’ll explore those.

Finally, if you’re reading this Daily on your smartphone, then you’ll want to read this: tips for setting up a shortcut from your home screen that puts you one tap from the latest Daily.