- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- With Elizabeth Warren out, women voters ask: ‘What now?’

- Caught in the middle: How Mexico became Trump’s wall

- ‘The heart of Australia’: Fires are out, but how to save the bush?

- Why your next lithium battery might come from the US

- Drawing on his roots, a rock guitarist finds a new rhythm in Nashville

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Coronavirus woes aside, there’s some good economic news too

Today’s stories examine women’s post-Warren political hopes, Mexico’s role in U.S. immigration policy, Australia’s environmental identity, a surprise bonus from geothermal brine, and a rocker returning to his roots.

When share prices plunge like melting snow off a steep roof and headline writers employ words like havoc, desperate, and panic, it’s pretty easy to worry. But fear tends to distort one’s view. To understand what’s really going on in the economy, it usually helps to take a deep breath and a step back.

The global economy indeed faces immense uncertainty in the wake of a novel and spreading virus. And it’s clear that it threatens to slow an already slowing economy as individuals and companies cancel travel, conferences, and other events. At the same time, some things are looking up for the consumer, such as energy costs, job growth, and falling interest rates.

Today’s failure of OPEC to reach a deal with Russia over cutting production may cause problems for its member nations. But an 8% drop in the oil price Friday means that gasoline prices should fall further.

Employers keep hiring. The latest 273,000 surge in jobs in February, also reported Friday, was far higher than many analysts expected and caused unemployment to fall back to the 50-year low set late last year.

And when the Federal Reserve tried to calm fears by cutting interest rates this week, it set off a mortgage refinancing boom. Homeowners who spend less in mortgage interest have more to spend on other goods, which should boost the economy.

None of this means that growth doesn’t face a late winter slowdown, perhaps a long one. The upbeat jobs report may not yet reflect the impact of the virus. But when nobody really knows how long winter will hang on, it’s important to acknowledge the green shoots that could herald spring.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With Elizabeth Warren out, women voters ask: ‘What now?’

What will it take to crack the final glass ceiling in U.S. politics? That’s the question women voters are asking after a record six women ran for president and fell short of the nomination.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

Is America still not ready for a female president? Elizabeth Warren’s decision Thursday to suspend her candidacy left only one of the record six women who entered the Democratic race still standing – a very distant Tulsi Gabbard.

With Hillary Clinton, it was understandable, Warren supporters say: She had baggage. Donald Trump was a wild card. But could it be pure coincidence this time around that voters didn’t go for any of these women, including the former California attorney general whose questioning of Brett Kavanaugh garnered her a national spotlight; the most effective Democratic senator in Congress, who won 42 Trump counties in her state; or the Harvard Law professor who predicted the financial crisis of 2008 and then spearheaded the effort to protect consumers?

Michelle Wu, a Warren Senate-campaign staffer who in 2013 was elected to Boston’s 13-member city council, says that’s all the more reason why passionate, visionary women should run.

“We need to translate that anger and disappointment into resolve to step up,” says Ms. Wu. “It’s not just one seat every four years ... The more women are serving on city councils and as governors, the more that also changes who we think could be president.”

With Elizabeth Warren out, women voters ask: ‘What now?’

Elizabeth Warren made a pinky promise that America couldn’t keep.

And for many girls, that is devastating. Not just for the ones in pigtails who met Senator Warren in selfie lines, wrapped their little finger around hers, and vowed to believe that a woman could be president. But also for the big girls in business suits – the CEOs and the mothers who told their daughters “dream big” as they tucked them into bed. They thought finally, here was a candidate so smart, so passionate, so competent that at last, they would see this dream come true.

And then they didn’t.

Instead, they saw a janitor’s daughter turned Harvard law professor emerge from her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, into the almost-spring sunshine and drop out of the 2020 race before the buds had a chance to blossom. She leaves two septuagenarian white male frontrunners and a very, very distant Tulsi Gabbard in a field that began as the most diverse in history with six women candidates.

With Hillary Clinton, it was understandable, Warren supporters say: She had baggage. Donald Trump was a wild card. But could it be pure coincidence this time that voters didn’t go for any of these six women, including the California attorney general whose questioning of Brett Kavanaugh garnered her a national spotlight; the most effective Democratic senator in Congress, who won 42 Trump counties in her state; and the Harvard Law professor who predicted the financial crisis of 2008 and then spearheaded the effort to protect consumers?

Then a woman asked the question on so many people’s mind: What role do you think gender played in this race?

“If you say, ‘Yeah, there was sexism in this race,’ everyone says, ‘Whiner!’ ” Senator Warren said. “And if you say, ‘No, there was no sexism,’ about a bazillion women think, ‘What planet do you live on?’ ”

Some 29 countries currently have a woman leader. Since 1950, women have led 75 countries. Just not the United States.

“The real concern is that people will say, why bother? If we don’t bother, and if women don’t run, they can’t get elected. So it’s never going to change if they give up,” says Kathleen Dolan, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. “Maybe feel badly for a few weeks and then maybe people who advocate for women candidates will get up and start working again.”

Boston city councilor Michelle Wu, a former student of and campaign staffer for Senator Warren, is one of those advocates – arguing that her mentor’s defeat should not deter but rather motivate passionate, visionary women to run.

“I know that it is infuriating and incredibly discouraging, but we need to translate that anger and disappointment into resolve to step up,” says Ms. Wu, who was one of only two women on Boston’s 13-member council when she was elected in 2013 and is now joined by half a dozen women councilors. “It’s not just one seat every four years. … The more women are serving on city councils and as governors, the more that also changes who we think could be president.”

Someone to ‘lead us out of the abyss’

But there’s a more difficult question, one which a woman who just poured her heart into a year-long campaign doesn’t answer before going back into the sanctuary of her home, which is: Even if there is a higher hurdle for women to clear en route to the White House, is that the main reason why Senator Warren’s campaign came to a creaking halt?

“There are reasons that candidates lose and men lose all the time,” says Professor Dolan. “Nobody looks at Cory Booker and says, ‘Why does that man fail?’ ”

But Warren supporters aren’t thinking about Cory Booker right now, or political science research. They are too sad. They need a moment.

In their minds, if someone had designed the perfect liberal female candidate, it would have been Elizabeth Warren. After Secretary Clinton’s loss in 2016, Senator Warren got them back on their feet, convinced them it could be different this time. She was the happy warrior, the best candidate they’d ever seen. If any woman could shatter that last glass ceiling in American politics, she could.

Now they’re left feeling that nothing will ever be good enough, no woman will ever get to the White House. Or not while they’re still around to see it, at least.

“It makes me so very sad,” says Mabe Wassell, an Illinois voter who had come to see the senator in a fluorescent-lit gym in Davenport, Iowa, across the Mississippi River not two months ago. “By the time I get to vote [on March 17], I get to vote for the lowest common denominator … two old men.”

“I feel the pain she might feel ... the feeling of being rejected, when I know she would have been an amazing, amazing leader,” says Caroline Yang, a Korean-American in Lexington, Massachusetts. She says she can relate to being discriminated against, having been passed over for the presidency of a local nonprofit in favor of a white person. “There is a certain bias against her that I think is unfair.”

It’s not just about advancing women, though. It’s about this extraordinary time in American politics.

“A lot of us, including myself, are feeling incredible anger and disappointment and sadness about the outcome of this primary,” says Debra Feldstein, who started a Women for Warren Facebook group dubbed the PerSisters. “Elizabeth Warren was probably one of the most qualified candidates we’ve had in recent history to lead us out of the abyss we’ve been led into by Donald Trump.”

‘Electability’ and the last glass ceiling

Ms. Feldstein lives in Santa Cruz, California, a coastal city of surfers and college kids that she calls “Bernie country.” His supporters are very outspoken, so much so that she thought she was alone in her choice of Ms. Warren. Then, one by one, her friends whispered that they, too, actually preferred the Massachusetts senator, but they planned to vote for their second choice because they considered her unelectable.

After more than a dozen of these conversations, Ms. Feldstein started the PerSisters Facebook group to give fellow Warren supporters a sense of community. In just two weeks, it grew to 856 women around the country.

But ultimately, it wasn’t enough. Senator Warren won fewer than 10% of the delegates that Sen. Bernie Sanders and former Vice President Joe Biden each collected on Super Tuesday, coming in third in her home state of Massachusetts.

“I think a lot of people didn’t vote their conscience because of fear,” says Ms. Feldstein, a consultant for women-led organizations who says there’s no question in her mind that a man with Senator Warren’s qualifications would have become the nominee. “There’s a view that people in our country hold, even women, of what looks and sounds like a president.”

Professor Dolan, author of the 2014 book, “When Does Gender Matter?,” says if you ask people why they don’t like the senator, they’ll say she’s hectoring or bossy. “These are the same people who are like, ‘Oh Bernie, he’s so passionate,’” she says.

But she also points out that Hillary Clinton, “who arguably had the most baggage of any woman who has run for president,” still got 3 million more votes than President Trump and did as well among Democrats as he did among Republicans.

There are many factors in elections. Gender is just one of them, she says, citing research that shows that women win as often as men when they run, and that the gender of candidates plays a minimal role in determining voters’ choices. But there’s also a wild card factor in this race.

“Donald Trump has broken everything about American government and American politics. And he has broken presidential elections … to the point that all Democrats care about is beating him,” says Professor Dolan. “Democrats are paralyzed with fear and they simply want to know who’s going to beat Trump. But the problem is, nobody knows who’s going to beat Trump.”

“They wanted the sure bet”

Surely Senator Warren could, the way she pilloried Michael Bloomberg on national TV and demanded that he unmuzzle the women who had lodged sexual harassment and discrimination complaints against him, her supporters say.

They blame the media for ignoring her, though there are quantitative challenges to that argument. They blame men – why can’t they be as enlightened as in Scandinavia? They blame other women, who they say were intimidated by someone as strong as Senator Warren. They blame political calculation over voting one’s conscience.

“People kept saying, ‘I can’t just follow my heart, I have to do the right thing,’” says Camille Brown, a New Hampshire voter. “And the right thing involved somebody else – because they wanted the sure bet. It’s too bad that people can’t just vote for the person who is the best candidate.”

But they have no regrets about their choice. And neither does she.

And maybe, they will find solace in signs of progress: in six women running for president this year, and what looks likely to be a record number running for the U.S. House and Senate, building on 2018’s record number elected.

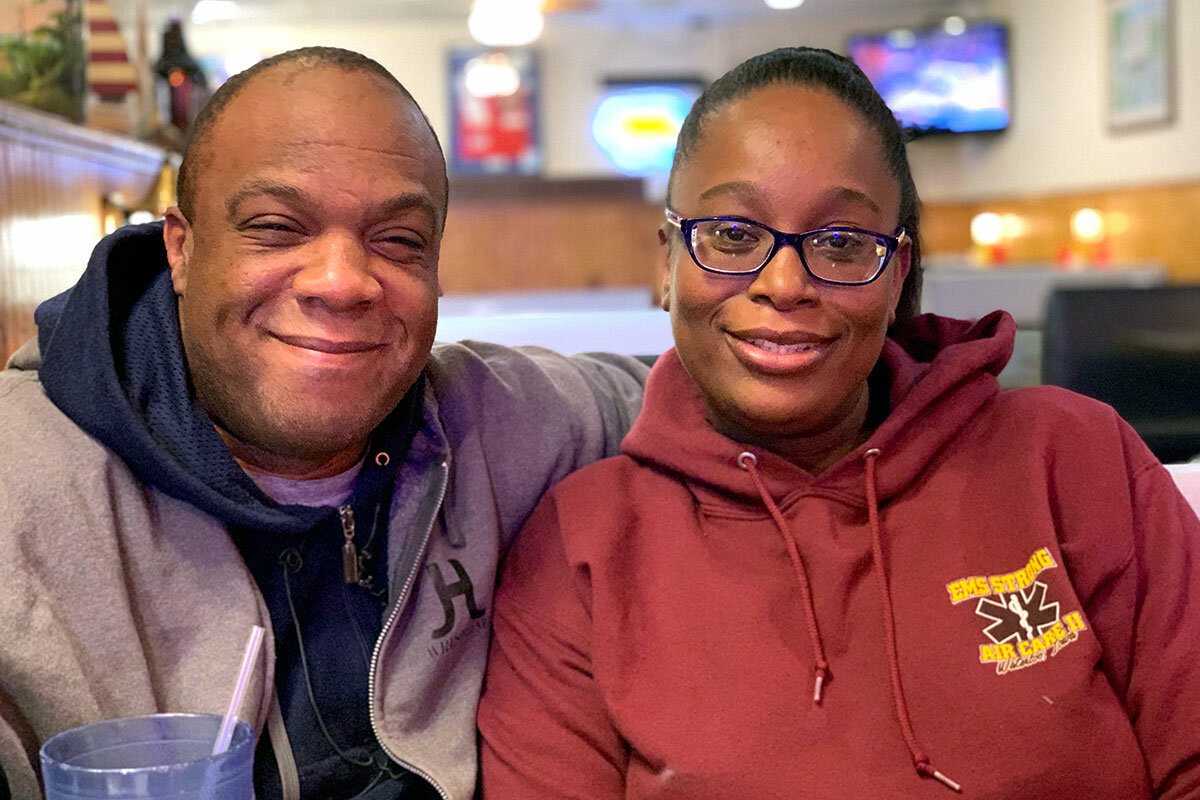

“Even though she is out of the race, what she’s done is really life-changing for me, especially because I’ve never been involved – but also people around me,” says Bridget Saffold, an African American woman who hosted the first-ever house party for a presidential candidate in her black community of Waterloo, Iowa, drawing 300 people to hear Senator Warren.

Many of those people had never been engaged before, including her best friend. Ms. Saffold has watched her go from the sidelines to the front lines, caucusing for the first time, finding her voice, and getting increasingly involved in city politics.

And then there’s all those younger girls the senator has inspired, like Karina Beltran, a high school junior in Los Angeles who got the news in the middle of sociology class.

“As soon as class ended, I got on Twitter and my eyes got watery, and my friends were like, ‘Are you going to cry?’ And I was like, ‘No, I’m not!’” she says. She did tear up later though. She had a lot invested in this race – and not just the dog-walking money she donated to the campaign. “I really hope I’ll be alive for the first woman president,” she says.

“One of the hardest parts of this is all those pinky promises and all those little girls who are going to have to wait four more years,” Senator Warren said Thursday, looking up in such a way that her friends might have asked her, are you going to cry? No, she didn’t.

The fight is still on.

Caught in the middle: How Mexico became Trump’s wall

In the second of our three-part immigration series, Mexico has come to fill a surprising place in President Donald Trump’s new system for curbing immigration.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The scene in front of Nikki Stoumen would have been extraordinary several years ago: a roomful of children, all trying to make their way to the United States.

Each of these tweens and teens left homes in Honduras and Guatemala, alone or with young siblings, to join the latest migrant caravan through Mexico. Edwin, fleeing gang recruitment, left his 12-year-old brother in charge. Diana fled after a gang member killed her family’s dog and cat, in retaliation for her younger brother accidentally breaking a window.

Today, they’re gathered in a sparsely decorated cafeteria in Mexico City, as volunteers like Ms. Stoumen try to explain the increasingly complicated realities of seeking asylum.

President Donald Trump’s long-promised border wall may not be complete. But overwhelmingly, the view from Central America is that the wall is a fait accompli – simply constructed further south.

Since 2017, the U.S. has profoundly changed asylum-seeking and migration: from separating families at the southern border, to ruling that domestic abuse and gang violence are not grounds for asylum. And Mexico has become central to those policies – despite its president’s vow to protect migrants’ rights.

“Mexico is building the wall for the U.S., and it’s a very, very visible wall,” says Alejandra Delgadillo, of the nongovernmental organization Asylum Access, referring to deportations on Mexico’s southern border.

Caught in the middle: How Mexico became Trump’s wall

It’s a tough crowd gathered around the white plastic tables in this sparsely decorated cafeteria on a recent morning. The eight boys and one girl awaiting a presentation are giving off universal signs of teenage ennui: hands splayed over faces, holding up their heads like they’re carrying the weight of the world, with zippers, baseball caps, and beanies perfect for fidgeting.

But these kids – ranging in age from 11 to 17 – aren’t your average tweens and teens.

Each picked up and, alone or with young siblings, left their homes in Honduras and Guatemala the week before to join the latest migrant caravan headed toward the United States. One 16-year-old, Edwin, said goodbye to his 12- and 8-year-old siblings, whom he’d been caring for alone for years after one parent moved to the U.S. and the other remarried and started a new family. He was fleeing gang recruitment – a clear pathway to a life of violence and early death – and poor prospects for education and work. The 12-year-old is now in charge back home.

“I’ll be able to help them out more if I’m safe and working in the United States,” Edwin says. The minors in this story are identified with pseudonyms for their protection. “Twelve isn’t that little,” he says, a reflection of how early childhood ends in many parts of Central America.

The fact that today’s know-your-rights meeting is focused on minors is a telling detail about how profoundly asylum and migration to the U.S. have changed over the past several years. As the U.S. repeatedly tweaks the rules of seeking asylum at its southern border, a roomful of children trying to understand their rights – once an extraordinary scene – has become more common.

“With Trump, asylum isn’t working,” says Nikki Stoumen, an American volunteer leading this session explaining possible paths to legal status in the U.S. for unaccompanied minors. She worked for years in Louisiana on Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) cases, one of the pathways she’s describing to these kids today.

“I can tell someone, ‘This is what is supposed to happen, what the U.S. says should happen,’ but things are up in the air right now,” she says. “We can’t be sure of anything.”

Overwhelmingly, the view from Mexico and Central America is that President Donald Trump’s long-promised border wall is a fait accompli – simply constructed further south. That transformation, critics say, has come with the assistance of Mexico’s new president, despite his campaign promises to defend migrants’ safety and rights as they pass through his country.

“Mexico is building the wall for the U.S., and it’s a very, very visible wall,” says Alejandra Delgadillo, who manages the Mexico programs for Asylum Access, an international nongovernmental organization, referring to deportations on Mexico’s southern border.

Mexican Ambassador to the U.S. Martha Bárcena put it bluntly in a January interview with The Christian Science Monitor: “To be totally frank – and I’ve said this [to] many congressmen – U.S. immigration and asylum laws are not working, and what you’re doing … is outsourcing solutions for your broken system to other countries.”

However, she pushed back on the idea that Mexico serves as a de facto buffer zone for its northern neighbor. “I wouldn’t say Mexico’s policy is turning people back,” or serving as an invisible wall, she said. “Mexico is trying to let people know that you also have to respect certain rules, including migration law in Mexico.”

Cross-border cooperation

Since 2017, the United States has taken steps to clamp down on its southern border, arguing drastic measures were necessary to deal with staff and detention shortages for the growing numbers of asylum-seekers. Changes have included executive orders and regulations that separate families entering the U.S., deport Central Americans to Guatemala to seek asylum there first, and send asylum applicants back to Mexico to await U.S. court dates, though a federal appeals court blocked the yearlong practice in February. The U.S. government has also created new limits to asylum, ruling that domestic abuse and gang violence will no longer be considered relevant factors, and implemented “metering” to control the number of people allowed to ask for asylum at a border crossing each day.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, meanwhile, came into office a little over a year ago touting a new approach to migration, centered on human rights. He said there was work for Central Americans in Mexico, and that they wouldn’t be criminalized for crossing the border.

Then came April 2019. After nearly 110,000 people were apprehended at or near the U.S. southern border – the largest monthly number in over a decade – President Trump threatened Mexico with tariffs if it didn’t do more to halt migrants and refugees arriving on the U.S.’s doorstep. Soon after, Mexico deployed its newly formed National Guard to its own southern border.

Deportations jumped almost immediately: More than 31,000 migrants were apprehended on the Mexico-Guatemala border in June 2019, the highest monthly total recorded since data became available in 2001. Abuse also soared, human rights experts say.

As the U.S. created more restrictions to asylum, Mexico continued to bear an outsize portion of the pressure. Between January and November 2019, Mexico’s refugee commission (COMAR) registered nearly 67,000 asylum applications, compared with roughly 29,600 in 2018. Asylum requests doubled or nearly doubled for three consecutive years. Meanwhile, COMAR’s budget was slashed to the lowest funding in seven years, about $1.2 million.

And it’s not just asylum-seekers in Mexico, where people are in theory guaranteed access to health care, education, and work permits, who are straining Mexican resources. Via programs like the U.S. Migration Protection Protocols, the recently blocked initiative commonly referred to as “remain in Mexico,” those seeking protection in the U.S. are waiting in some of Mexico’s most dangerous cities and states for months.

“Migrants are suffering more,” says the Rev. Luis Eduardo, who runs the migrant shelter Casa Nicolas, about 2.5 hours from the U.S. border in the state of Nuevo León. He’s seen fewer people arriving over the past year, which he believes is due to Mexico’s crackdown. But most are staying longer, as they try to create a plan that balances safety with the ever-changing realities on the U.S. border.

“The U.S. doesn’t want them, which the government’s policies have made clear. Mexico is detaining and returning them forcibly and complementing U.S. policy. Where does that leave us?”

High-stakes choices

Like many migrants hoping to make it to the U.S., 16-year-old Diana starts by describing her story in generalities: Honduras is dangerous. Criminals are so ruthless there, she says earnestly, even dogs and cats are under threat.

Ms. Stoumen nods and inhales deeply. She and a lawyer from the Mexico City-based NGO Institute for Women in Migration, which helped organize today’s visit, have offered to speak with the teens one-on-one about their situation after the information session wraps, though they can’t offer specific legal advice. “I know crime is horrible,” she says. “But asylum isn’t for generalized violence.”

Diana, with one arm in a sling and shoulders covered by a bubble-gum pink sweatshirt, goes a little deeper. Her 7-year-old brother was throwing rocks and accidentally broke a gang member’s window. He came for her brother at school, intimidating him. Then he came to the family’s home and threatened them, killing their dog and cat.

“I want to be something in life. If I can get support here and can study, I’ll stay,” she says, weighing her desire to study computer science in the U.S. with the risks of continuing her journey beyond Mexico.

Of the kids Ms. Stoumen has met today, she thinks one might have a chance at SIJS, which is reserved for minors who have been abandoned, abused, or neglected by their family and have relatives who can care for them in the U.S. Despite challenging home lives and dangerous communities, few of them would make it far in the U.S. asylum process, she suspects.

The makeup of migrants passing through Mexico has changed dramatically in recent years, says Eréndira Barco, the social worker at the Scalabrini Mission with Migrants and Refugees Casa Mambré shelter where the information session is taking place. Whereas in the past there were primarily single men motivated by economic opportunities, the main reason migrants staying in the shelter tell them they’ve left home is now violence, she says. The number of unaccompanied minors and family units has also shot up.

“The reality of the situation on the U.S. border is starting to sink in,” Ms. Barco says, of migrants staying at the shelter deciding if Mexico will be a part of their journey or the end point. “But many continue to fight” to make it to the U.S.

She expects most of the kids at today’s information session will return home, though. They’re young, they’ve been through a lot, and they’re starting to realize how hard it is to calculate their futures.

“I just want to be safe,” says 16-year-old Jorge, who describes unwanted recruitment from two opposing gangs pushing him to flee Honduras. “I can’t go home. My country is …” He trails off for a moment, looking out the cafeteria window to a bustling Mexico City street.

“If I go back home, I’ll die.”

Reporters on the Job

Monitor correspondent Whitney Eulich gives the inside scoop

A group of boys played a rowdy game of chess while I sat on a nearby couch, waiting for a migration shelter’s social worker in late January. The youngest, 11 years old, kept hooting in support of his new friends. “Wow! What a move!” he cried for one. “That’s it!” He shrieked for another. The teens around him high-fived and giggled so naturally, it almost didn’t register that just days ago they’d each made incredibly complex, adult decisions to leave home.

I’ve spent the past decade reporting on migration across Central America and Mexico, and it’s sometimes easy to go numb to the stories of violence, corruption, and poverty that drive so many people to migrate or flee. Despite the brave, serious faces these boys put on later that morning when telling me about their dreams and the often dreadful reasons they finally left home – I had this scene of youthful glee playing in the back of my mind.

Whichever country they land in, I only hope they get to spend more time laughing with friends than running for their lives.

‘The heart of Australia’: Fires are out, but how to save the bush?

After a summer of fire, followed by flood, Australia must reckon with questions about preserving the natural bounty so essential to its self-identity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Torrential rains last month brought relief to Australia after a summer of fire. The toll included 34 people, an estimated 1 billion animals, and some 27 million acres – but also wounds to the national psyche.

“What would Australia be without the bush?” says Monique Maul, who co-owns a cafe in Kangaroo Valley. The town of 900 has seen its bush-reliant economy hurt as visitors stay away and farmers lost livestock and rangeland.

“People come here from all over the country and the world to see our wildlife, forests, and beaches,” she says. “That’s the heart of Australia.”

Australia’s nature is at the heart of its identity, and economy. Now, the government faces a reckoning over how to change course, particularly in its fossil fuel sector. But as smoke-filled air over major cities fades away, some fear heightened awareness will recede, as well.

“Australians are very good at post-event resilience – at coming together and overcoming crisis,” says Jerry Courvisanos, of Federation University. “But then we fall back into the old ways. We aren’t good at pre-event resilience – preparing to transform ourselves and the way we live.”

‘The heart of Australia’: Fires are out, but how to save the bush?

Lorena Granados and Gaspar Roman stood behind three folding tables that held the salvaged remnants of their shared dream. On New Year’s Eve, as a bushfire bore down on their leather goods business, they fled with a random array of handmade wallets, belts, purses, and bags. Three weeks later, they displayed the items for sale in front of their store’s charred ruins, greeting friends and customers as they accepted condolences and wiped away tears.

The couple moved into the shop from a smaller space down the street four months before the blaze ripped through Mogo, a tourist enclave along Australia’s southeastern coast. Ms. Granados estimates they spent $2 million (Australian; U.S.$1.3 million) to purchase and renovate the store, and their insurance will cover only about one-fifth of the cost.

The loss of their nearby home – one of dozens of houses destroyed in the town of 300 residents – deepened the couple’s misfortune and their sense of unease about the country’s future. Their feelings mirror sentiments across Australia after a bushfire season of unprecedented devastation.

“We can’t keep doing what we’ve been doing,” Ms. Granados says. “If the government won’t take action, then we – as communities, as business owners – need to start changing or we’ll face these disasters every year.”

Torrential rains brought relief to Australia in early February after a summer of fire that scarred some 27 million acres and the national psyche. The death toll included 34 people and an estimated 1 billion animals, and 57% of Australians reported a direct impact from the flames, smoke, or both.

Climate scientists had warned for decades that global warming could contribute to larger, more destructive bushfires on the continent. The arrival of that apocalypse has sown anxiety in a country that in the past has prevailed over adversity with its optimism intact.

In the aftermath of the fires, Australia must reckon with questions about preserving the natural bounty essential to its self-identity and about its dependence on fossil fuels to propel the economy. Finding solutions will hinge on the country’s willingness to embrace sacrifice, asserts Philip Lawn, an ecological economist with the Wakefield Futures Group, a nonprofit based in Adelaide that advocates for sustainable development.

“The problem is that most people don’t know what has to be done to deal with the climate change emergency,” he says. “They don’t realize that it will require each person to alter the way they conduct their lives.”

‘It’s up to us’

The career switch that Mark and Kristen McLennan made in 2015 moved them out of the classroom and on to the farm. Motivated by an ethos of sustainability, the former school teachers began raising chickens in Kangaroo Valley, a small town in the Southern Highlands between Canberra and Sydney.

The couple’s original flock of 50 birds grew to 7,500 over time as their pastured egg business attracted an expanding client list of cafes, restaurants, and groceries. But their steady progress stalled in late December when, days before a bushfire scorched the valley, temperatures reached 120 degrees and 2,000 chickens succumbed to the heat.

The McLennans estimate they will need to invest $200,000 to recover from their losses. (All dollar figures are in Australian.) The prospect of seasonal catastrophes as temperatures rise – Australia recorded its hottest and driest year in 2019 – worries them as small-business owners and as parents of two young daughters.

“The idea that this summer could very well be the norm is alarming,” Ms. McLennan says. “We can’t just keep assuming the bush will keep coming back.”

Kangaroo Valley, a town of 900 residents, runs on a bush-reliant economy of tourism, outdoor recreation, and sustainable farming. The summer fires hurt all three sectors as visitors stayed away and farmers lost livestock and rangeland.

Domestic travelers make up three-quarters of Australia’s tourism market, and the slow foot traffic in shops and restaurants on the town’s quaint main street reflected their absence. At a cafe called The General, co-owner Monique Maul suggested that the country has neglected the duty of caring for its natural wonders and, in turn, jeopardized a vital cog in its economy.

“What would Australia be without the bush?” she says. “People come here from all over the country and the world to see our wildlife, forests, and beaches. That’s the heart of Australia.”

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has pledged $76 million in aid to revive the country’s tourism industry. The figure pales compared with the Australia tourism council’s estimate that the fires cost businesses $4.5 billion.

The fallout extends beyond financial burdens for those who live and work in the bush. They feel a visceral bond with the land, and the destruction represents an open wound.

Toni and Rob Moran run a wedding venue in Kangaroo Valley that offers vistas of the surrounding hillsides. Flames turned the forest views from green to black this summer, and while their business survived, the couple fear the country will fail again to act on the bush’s behalf.

“It felt like all of Australia was burning,” Ms. Moran says. “It’s pretty obvious what Mother Nature is telling us. It’s up to us to decide whether we’ll listen.”

A need for action

Some 85% to 90% of Australia’s 25 million people live in cities. The population disparity between urban and rural areas poses an obstacle to boosting efforts to preserve the bush, contends Jerry Courvisanos, an associate professor of innovation and entrepreneurship at Federation University in Ballarat.

The scenes of bushfire devastation broadcast around the world and the smoke-filled air that hovered over Canberra, Melbourne, and Sydney have faded away in recent weeks. For Australians in urban centers, Mr. Courvisanos explains, the cataclysm – and a sense of urgency about addressing the causes of climate change – has begun to recede in memory even as the bush and its wildlife struggle to recover.

“Australians are very good at post-event resilience – at coming together and overcoming crisis,” he says. “But then we fall back into the old ways. We aren’t good at pre-event resilience – preparing to transform ourselves and the way we live.”

The bushfires stoked criticism of Mr. Morrison for his climate policies and allegiance to fossil fuel industries that contribute to greenhouse gases. In response, he shifted his rhetoric, speaking of the need to bolster the country’s “resilience and adaptation” to cope with global warming. Yet he has shown little inclination to rein in a fossil fuel sector that makes Australia one of the world’s leading exporters of coal, liquefied natural gas, and iron ore.

At the same time, if the potential for federal policy reform appears low, the push toward sustainability at the state level has gained momentum the past few years. Officials in New South Wales and Victoria, the two states hit hardest by the bushfires, have rolled out formal economic initiatives to improve energy efficiency, reduce waste, and cultivate sustainable growth.

Open Cities Alliance, an association based in Sydney, works with public officials, urban engineers, and utility providers to nurture sustainable communities. Lisa McLean, the group’s chief executive, regards the state strategies as evidence that Australians are willing to adopt new living habits that lighten their impact on nature.

“People are feeling the effects of climate change very deeply, as the fires have shown,” she says. “So we can’t keep the focus only on preparing for climate change. We have to take action to prevent it.”

Ms. McLean holds hope that the perennial allure of vacationing in the bush will persuade urban dwellers to act to save the country’s flora and fauna. “Most Australians have a connection to nature even if they live in the city. It’s something that’s part of our character,” she says. “When they see what the fires have done, it will show them we can’t keep taking things for granted.”

The sentiment resonates with Diane McGrath, who manages the Edgewater Motel in Burrill Lake. Bushfires early in the year forced a mass evacuation of the coastal tourist town, and the motel’s business for January fell by 80% over last year. She frets that recurrences of the summer of fire will destroy more than the bottom line.

“The federal government is looking after the mining industry,” she says. “But if we don’t look after our natural resources, what kind of Australia are we leaving for future generations?”

Reporters on the Job

Monitor correspondent Martin Kuz gives the inside scoop

An ashen dusk settled over Morton National Park as I drove along a dirt road in Australia’s Southern Highlands in late January. Bushfires had skinned the area bare days earlier, and as infernos continued to burn nearby, acrid smoke suffused the desolate silence. Nothing appeared alive.

A blur of movement to my right caused me to hit the brakes. A few feet away, an enormous kangaroo sprang into the road, looking about the size of a T. rex in the dying light. I watched its bounding form vanish into the blackened forest as my eyes returned to their sockets.

Heavy rains finally ended the country’s devastating bushfire season a few weeks later. An estimated 1 billion animals died as the flames scorched more than 27 million acres (42 square miles), and the massive loss of habitat suggests that the wildlife death toll will climb in coming months.

I wonder if that giant marsupial has survived. I wonder if it can outlast another summer of fire.

Why your next lithium battery might come from the US

Lithium is proving to be a critical resource in modern society. But obtaining that mineral isn’t always easy – or green. Could a solution lie in the California desert?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Chris Iovenko Contributor

Demand for lithium is expected to grow exponentially as electronic devices proliferate, energy storage demands rise, and combustion engines are replaced by electric counterparts. The U.S. government has designated the mineral as critical to national security and the economy – and yet currently, lithium comes from foreign regions that in many cases are politically unstable or pose other challenges for the United States.

But a domestic supply may be on the horizon. Several energy companies are focusing on the vast underground geothermal reservoir at California’s Salton Sea as a source of lithium. The recovery process would be added to new or existing geothermal plants, which produce a continuous and controlled stream of clean power.

“Mineral extraction will make for a much better profit picture for geothermal,” says Jim Turner of Controlled Thermal Resources, whose proposed new string of geothermal power plants will be the first purpose-built to also produce lithium.

Berkshire Hathaway Energy, which operates 10 geothermal plants at the Salton Sea, also is hoping to build a demonstration lithium reclamation plant. Says BHE’s Jonathan Weisgall, “The potential is huge.”

Why your next lithium battery might come from the US

The view from the southern end of the ever-shrinking Salton Sea in California’s Imperial County is stark but strangely beautiful. A boat launch is marooned a mile from the far-off glitter of the lake’s edge. Geothermal plants spout plumes of gray steam from their distinctive circular cooling towers.

But it is something out of sight that’s launching activity these days in this desert valley.

Several energy companies are focusing on the Salton Sea’s vast underground geothermal reservoir as a source of lithium – the valuable alkali mineral integral to the batteries used in phones, laptops, electric cars, and everything in between.

Currently, lithium is mined overseas, primarily in South America and China, using extraction processes destructive to the environment. In contrast, the activity at the Salton Sea represents the possibility of having a domestic supply of lithium – and for the process to be green as well as cost-competitive.

To be sure, past ventures at the Salton Sea show how challenging and fraught such endeavors can be. Nevertheless, the underground reservoir here beckons as an untapped, important, and potentially very valuable resource.

“The Salton Sea’s geothermal brine has high concentrations of lithium that are unique in the world,” says Jens Birkholzer, director of the Energy Geosciences Division at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “It has to be extracted efficiently and cost-effectively, but it could be a huge boon for the area and could also make geothermal more competitive.”

One of the largest liquid geothermal reservoirs in the world is here at the southern terminus of the San Andreas fault. Geothermal energy production began in the area in the 1980s but has encountered setbacks. The drive now is to add lithium production facilities to new or existing plants.

The basics of geothermal

The principle of geothermal energy production is relatively simple: Wells, which can be more than 8,000 feet deep, are drilled down into the reservoir. The pressurized, superheated mineral-rich brine is routed up through pipes to cooling towers where the brine is vaporized. The resulting steam is captured and harnessed to energy-producing turbines.

However, geothermal plants are expensive; a single well can cost up to $16 million, and the overall cost of a commercial plant can top $500 million. Additionally, the cost of wind and solar energy production has dropped dramatically in recent years, rendering new geothermal plants uncompetitive in the energy marketplace.

That’s where lithium comes in. By adding lithium reclamation to the facilities here, there’s a tantalizing opportunity to make geothermal energy production cost-competitive with other renewable power sources.

Reclaiming lithium from geothermal brine is an almost completely green and sustainable process. While the brine is out of the ground for power production, lithium can be extracted, too. The power needed for lithium recovery comes from the geothermal plant itself, and therefore the carbon footprint is minimal. And when the recovery process is completed, the leftover brine is injected back into the depths of the reservoir, where it has time to heat up before being tapped again.

One of the companies that is bullish on this process is Controlled Thermal Resources, an Australian company with operations in California. On a recent day at the Salton Sea, Jim Turner, CTR’s chief operating officer, stands atop a bare windswept hill no longer surrounded by water but still known as Red Island. A muddy playa, or dry lake bed, lies directly below.

“We have about 7,300 acres out there under our control. Our part of the resource goes for about a mile and a quarter past Mullet Island,” he says, pointing toward a distant hump of land that also is no longer an island. “As the sea recedes it will expose more and more playa, which will eventually allow us to complete the development.”

CTR’s proposed new string of geothermal power plants will be the first purpose-built to also produce lithium.

“In addition to a series of replicant geothermal power plants, we’ll have a lithium plant that will produce about 17,000 metric tons of lithium annually,” says Mr. Turner. “The power plants today make money, but they’re not big rates of return. Mineral extraction will make for a much better profit picture for geothermal.”

Geothermal’s salient advantage is that it produces a controlled stream of clean power around the clock. Such a mainline power source could supplement and back up power grids supplied by intermittent renewable energy sources like wind and solar. The geothermal reservoir at the Salton Sea, if fully tapped, could provide power to an estimated 2.3 million-plus homes, and could play a significant role as California tries to reach an ambitious goal of getting 50% of its energy from renewable sources by 2030.

Demand for lithium is expected to grow exponentially as electronic devices proliferate, energy storage demands rise, and combustion engines are increasingly replaced by electric counterparts. The U.S. government has designated the mineral as critical to national security and the economy – and yet currently, lithium comes from foreign regions that in many cases are politically unstable or pose other challenges for the United States.

Damaged ecosystems overseas

Most lithium comes from the so-called Lithium Triangle, which spans Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile. Here, vast man-made evaporative lakes are rich in minerals, but these lakes use enormous and increasingly scarce quantities of water. As a result, desert ecosystems are being destroyed and hardships have grown for local residents. The remaining lithium comes chiefly from China and Australia, where the mineral is extracted from crushed rocks. This hard rock open-pit mining also damages ecosystems, and the toxic chemicals used to process out the lithium can contaminate soil, streams, and groundwater. Moreover, hard rock mining has a large carbon footprint.

Mr. Turner makes distinctions about the impact that CTR’s process would have on the environment. “Ours is a totally closed-loop system,” he says. “Everything’s in pipes and vessels, and you can control the whole thing. We’ll have almost a completely green process here.”

This isn’t the first time that lithium extraction has been tried at the Salton Sea. Energy company Simbol Materials had a pilot lithium production facility that created a lot of excitement; Elon Musk, the Tesla CEO, offered to buy the company in 2014 for $325 million. But the deal fell apart, and Simbol went out of business.

Berkshire Hathaway Energy, which operates 10 geothermal plants at the Salton Sea, also developed mineral reclamation techniques using brine, back in 2002 – for zinc. But two years later after disappointing results, BHE halted zinc reclamation activities. However, the company is again actively interested in mineral recovery – this time, of lithium. BHE is hoping to build a demonstration lithium reclamation plant that would establish the commercial viability of lithium production at its current facilities.

“The potential is huge,” says Jonathan Weisgall, vice president of government relations at BHE. “If this really goes, our existing geothermal plants could produce up to 90,000 metric tons of lithium a year. That would satisfy more than one-third of the entire worldwide demand for lithium today. And everyone agrees that there will be a fourfold increase in demand. There’s a tremendous potential for expansion.”

Yet Simbol’s collapse, as well as BHE’s failed experiment with zinc production, demonstrates the pitfalls. And geothermal brine presents a formidable chemistry problem; it contains corrosive minerals and other contaminants that need to be efficiently separated out to create market-grade lithium.

Still, the benefits of having a domestic and green supply of lithium are numerous, and the lithium resources at the Salton Sea are epic in scale. In fact, if the entirety of this geothermal reservoir were to be fully utilized, the ensuing lithium production would have the potential to not just meet but exceed global lithium demands for years to come.

“If you were to expand the geothermal resource and while also extracting lithium, you could go out to a factor of 5 or 10 times the current world usage of lithium,” says Dr. Birkholzer of the Berkeley Lab. “It would have to be extracted efficiently and cost-effectively, but the resource is clearly there.”

Drawing on his roots, a rock guitarist finds a new rhythm in Nashville

Taking risks artistically can lead to new ways of thinking. When Jonathan Wilson, a detail-oriented musician, loosened his control over the final product, he found a new approach to expressing himself.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When he was young, songwriter Jonathan Wilson played guitar in the Baptist church in Spindale, North Carolina, where his grandfather was a preacher and his grandmother was choir director. “When I would sit and compose some of my early stuff, I would try to join up with some sort of meditative ... spiritual element,” he says.

Nowadays, the tricky part of songwriting is finding the mental space because he’s “tethered to the phone and the ’gram,” says the in-demand session player, co-writer, and producer for the likes of Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters and Lana Del Rey.

His new album, “Dixie Blur,” is the antithesis of its lush predecessor. It’s a rustic Americana album recorded entirely live in just six days. With it, the musician has adopted a pared-down, roots-driven path to his latest sound.

“This definitely was my first time to let go and trust in the process to this extent,” says Mr. Wilson, who explains his habit has been to endlessly tweak recordings to perfect them. “It’s going to be a lot more powerful to ... actually hear that sort of a purity of a document that was done in a certain time with some soft songs.”

Drawing on his roots, a rock guitarist finds a new rhythm in Nashville

Until recently, songwriter Jonathan Wilson recorded his solo albums the way he handcrafts his own guitars as a luthier. An auteur and multi-instrumentalist who’s as comfortable behind a studio mixing console as he is behind a drum kit, he would painstakingly chisel and lathe each layer until the final album gleamed under its lacquered varnish.

But after spending nine months recording the 2018 album “Rare Birds” – a “maximalist” production with 1980s touchstones such as Fleetwood Mac’s “Tango in the Night” – Mr. Wilson yearned “just to go somewhere, get completely out of my zone, and to do something completely different.”

His new album, “Dixie Blur,” is, in every way, the antithesis of its lush predecessor. It’s a rustic Americana album recorded entirely live in just six days with a group of strangers in a completely foreign environment. He’s left splinters in the record – adopting a pared-down, roots-driven path to his latest sound.

“Folks might look to me for like a psychedelic, rock-y, California song vibe or something like that. I wouldn’t want to get into the conundrum of trying to constantly be that guy,” says Mr. Wilson, also an in-demand session player, co-writer, and producer for the likes of Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, Lana Del Rey, and Father John Misty. “It bums me out when I hear artists that make the same song again.”

Credit Americana icon Steve Earle for inspiring the concept for “Dixie Blur” during a radio program last year. “We were doing this NPR show and he was like, ‘Maybe you should go to Nashville,’” recalls Mr. Wilson, who is based in Los Angeles.

After that, he called up his friend Patrick Sansone from the band Wilco to co-produce the album and also act as a guide to the best studio and session musicians in Tennessee.

It seemed to Mr. Wilson that the songs he’d been working on could work with instruments such as fiddles and pedal steel guitar. After composing “Rare Birds” on a Steinway piano, Mr. Wilson returned to writing on an acoustic guitar for the latest album. It simplifies things harmonically, he says. Just strumming a G chord suggested a more bluegrass and country feel. Of late, he’d also begun to reflect on his own Southern roots in lyrics such as those on the autobiographical new “69 Corvette.”

Mr. Wilson, who has a night job as one of the principal guitarists and vocalists in Mr. Waters’ band, wrote the song during a 157-date world tour with the former Pink Floyd songwriter. The song’s refrain about missing home emerged during a several-day layover in “Poland or something,” he says, expressing the disorientation of a touring musician who’s crossed more time zones than a satellite.

The artist recalls “just walking around the city by myself, going to vintage rock and clothing stores for the fifth or the 18th time.” He returned to his fancy hotel, picked up his guitar, and thought to himself, “‘Wow, this is a weird place to be from the place that I started,’ which was a little tiny town where there was nothing going on.”

Before he became a teen guitar hero in Spindale, North Carolina, Mr. Wilson played in the Baptist church where his grandfather was a preacher and his grandmother was choir director. It gave the songwriter an appreciation for the relationship between music and spirituality: “When I would sit and compose some of my early stuff, I would try to join up with some sort of meditative ... spiritual element.” Nowadays, the tricky part of songwriting, he says, is finding mental space because he’s “tethered to the phone and the ’gram.”

“It can be hard, but I usually get to a place where I’ve got my piano and I can sit while the rest of the planet is in bed,” he says. “That’s the quiet time. And so that’s when the stuff comes.”

The Nashville recording sessions for “Dixie Blur” at Cowboy Jack Clement’s legendary Sound Emporium Studios offered a different sort of communion. Mr. Wilson felt instant musical kinship with session luminaries including Dennis Crouch (bass), Russ Pahl (pedal steel guitar), and Mark O’Connor (fiddle). Beneath the dusky lights in Studio A, where wooden awnings cast shadows over the parquet floors and Persian rugs, they recorded songs ranging from the furious gallop of “El Camino Real” to the slow lament of “Riding the Blinds.” Mr. Wilson thrived on the feedback of seasoned players who said, “Don’t bore us; get to the chorus.” The process allowed for spontaneity to change the tempo, the key, and the feel of the melodies – sometimes at the suggestion of the musicians.

“If the album would have been done here in Hollywood, those guys would have been asking for publishing [rights],” he jokes.

Next, the songwriter has a solo tour for “Dixie Blur,” which, he says, has the feel of a classic album.

“This definitely was my first time to let go and trust in the process to this extent,” says Mr. Wilson, who explains his habit has been to endlessly tweak recordings to perfect them. “It’s going to be a lot more powerful to ... actually hear that sort of a purity of a document that was done in a certain time with some soft songs.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

For climate action, lessons from the virus crisis

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Two of the world’s biggest challenges – the coronavirus scare and climate change – differ in many ways. Yet in one, the virus challenge, there may be lessons for the other.

With the coronavirus, countries are focused mainly on their own people. Yet they are also cooperating at a pace and intensity rarely seen on a global scale. Companies are speeding up production of needed goods. Central banks in the G-7 group of Western economies are consulting on the lowering of interest rates. And dozens of nations are working through the World Health Organization to share information and resources. The level and speed of such actions have not been lost on climate activists.

In response to the virus, billions of people have changed their habits in a matter of weeks. They have welcomed tough action by government. They see personal sacrifice as necessary for the public good. Now they may be more willing to accept similar action to guard public health from climate change. If the world can sing in tune on one crisis, it makes it easier to do the same for another.

For climate action, lessons from the virus crisis

Two of the world’s biggest challenges – the coronavirus scare and climate change – differ in many ways. Yet in one, the virus challenge, there may be lessons for the other.

Just three months ago the idea of a new virus spreading quickly across the globe was not in public thought. Now countries have sprung into action. Yet for decades the world has debated climate change with little to show in reduced carbon emissions. How did concern for the coronavirus leapfrog over climate change in priority?

The answer, of course, is that the virus is seen as an immediate threat demanding immediate action. Climate change is slow-moving, like the proverbial frog in the cooking pot. The effects of rising temperatures are imperceptibly tolerated until it is too late to hop out. Yet now as a result of the virus crisis, more people could be persuaded to act on the scientific predictions about global warming.

Both challenges are also reminders that problems in far corners of the planet – coal pollution, health crises, terrorism, etc. – should not be ignored. Advances in globalization, especially in travel and technology, act as accelerators. Humanity is linked like never before. This forces people to work together to solve problems rather than going it alone.

With the coronavirus, countries are focused mainly on their own people. Yet they are also cooperating at a pace and intensity rarely seen on a global scale. Companies are speeding up production of needed goods and health-care supplies. International aid groups are coordinating to beef up their response.

World bodies such as the International Monetary Fund have dispensed emergency money to help countries cope with the virus. Central banks in the G-7 group of Western economies are consulting on lowering of interest rates to support financial markets. And dozens of nations are working through the World Health Organization to share information and resources.

For Americans, there has been rare bipartisanship in Congress to work with President Donald Trump in providing an additional $8.3 billion to battle the virus.

The level and speed of such actions have not been lost on climate activists. “If we truly treat climate as an emergency, as we are treating this pandemic as an emergency, we have to have a similar level of international coordination,” notes Jon Erickson, an ecological economist at the University of Vermont.

In response to the virus, billions of people have changed their habits in a matter of weeks. They have welcomed tough action by government. They see personal sacrifice as necessary for the public good. Now they may be more willing to accept similar action to guard public health from climate change. If the world can sing in tune on one crisis, it makes it easier to do the same for another.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

In one affection

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Keith Wommack

What if we all took a moment to pray to feel and express more of God’s love in our communities and our world, today – this year’s World Day of Prayer – and every day? Here’s an article that illustrates how powerful such prayer can be.

In one affection

People in over 170 countries are uniting today in this year’s World Day of Prayer. The focus is on women and children. Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, loved them both. And she loved to pray. She wrote, “True prayer is not asking God for love; it is learning to love, and to include all mankind in one affection” (“No and Yes,” p. 39).

Twelve days before my wife, Joanne, and I were married, Joanne agreed to babysit a friend’s two children. Joanne’s two small boys played with her friend’s children, and in the evening she tucked them all in bed together.

A few days later, Joanne’s friend anxiously let us know her daughter now had chicken pox. This friend offered to care for Joanne’s boys during our wedding if they became ill. Joanne assured her that her offer was generous but that all was well. She told her not to feel guilty or be afraid; we would see her at the wedding.

Then Joanne and I prayed together, affirming that God, who is infinite Spirit, never created or allows suffering. There were anxious moments when fear tried to sneak into our thoughts. Yet the fear of contagion only forced us to go deeper in our prayer to discover spiritual laws upholding our health and God’s unending goodness and love. Divine Love had motivated Joanne to babysit, and divine Love embraced this precious little girl as well. And as the Bible says, perfect Love casts out fear (see I John 4:18).

To us, then, it was no surprise that the wedding took place as planned. Joanne’s boys participated in the wedding, untouched by that contagion. Joanne’s friend and her family were also at the wedding, and her daughter looked great.

As we pray, today and every day, let’s learn to love more, “and to include all mankind in one affection.”

This also aired on the March 6, 2020, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

Getting an education, no matter what

A look ahead

That’s a wrap for today. Be sure to come back Monday when we take an international look at the forces of deglobalization.