- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- From Milan to Miami, locked-in nations try to soften an economic blow

- Moral quandary: How to help people without putting them at risk

- A health officer with a fan club? Meet Canada’s Dr. Bonnie.

- Not just for the military: More chaplains come to employees’ aid

- Feel-good flicks to watch at home while social distancing

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Live from living rooms, the comfort of reading aloud

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

Today’s stories explore efforts to mitigate the economic impact of the coronavirus around the world, the dilemma that social distancing presents for those who serve the homeless and elderly, the compassionate leadership of a health official in British Columbia, the trend toward hiring chaplains for workplaces, and feel-good movies from the Monitor’s film critic.

When was the last time you read a book out loud? Or had one read to you?

A staple of grade school classrooms, the read aloud is taking on a new role: balm in a crisis.

Online hashtag campaigns #OperationStorytime and #savewithstories are in full swing this week, featuring celebrities and authors reading from their couches and dens. They are bringing attention to out-of-school students who need food, or choosing on their own to comfort people of all ages during a troubling time.

“I’m gonna read to you and your children, or just you, depending on what you prefer,” said Josh Gad, the voice of Olaf in the “Frozen” movies, before launching into the book “Olivia Goes to Venice,” on Friday. He now reads nightly on social media, calling his effort, viewed by hundreds of thousands, the #GadBookClub.

When Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in 2017, we reported on a Facebook book club started by a teacher wanting to offer a distraction to displaced kids. Toddlers and teachers, fourth graders and authors all came to the group to record themselves reading favorites from their shelves.

Read alouds will become even more common in the coming months, as teachers increasingly use them (with permission from publishers) in virtual classrooms and turn to authors as resources. But as Mr. Gad alluded to, the calm and connection that comes from being read to isn’t just for kids. It’s for everybody.

Be sure to scroll to the end of today’s Daily edition. We wanted to share a snapshot of our morning meeting, with staff around the world convening by video. We found it buoying, and hope you will as well.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

From Milan to Miami, locked-in nations try to soften an economic blow

Turmoil in financial markets reflects widespread fears over a global recession amid the coronavirus pandemic. How policymakers respond could be critical to the length and depth of such a recession.

Katja Sator owns an auto-parts plant in Germany that is still running, despite a sudden halt at many automakers. Technicians on the production lines work 2 meters (6 1/2 feet) apart to reduce the risk from the coronavirus that has begun to decimate the global economy.

Germany, the United States, and other major economies have begun to inject money into their stricken economies, providing credit to companies like Ms. Sator’s. She’s hesitant to go into debt, given the uncertainty in her industry and others, but relieved that policymakers are acting.

What’s not clear is whether fiscal policy will be strong enough to cushion the blow of a health emergency that has idled workers and emptied schools and offices. Economists predict a severe contraction in economic activity and a surge in unemployment. The challenge for policymakers is to keep workers attached to their employers so that businesses can rev up once the worst is over. Simply bailing out struggling companies may not in itself solve that problem, which is why Congress may soon be cutting checks to American families so that spending doesn’t crash.

“It’s like we’re firefighting – first dropping water on the whole building,” says Ioana Marinescu, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania.

From Milan to Miami, locked-in nations try to soften an economic blow

It’s a seemingly intractable dilemma, suddenly as salient in Berlin or Tokyo as it is in Washington: How do you save people’s economic livelihoods while telling those same people to stay home?

A global recession, many forecasters say, is already here and is growing more severe by the day, as millions of consumers and workers in Europe, Asia, and North America have been sidelined as governments take extreme measures to stem the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, though, actions by governments and central banks appear to be ramping up, not so much in an effort to prevent a recession as simply to weather a storm that could easily become more severe than the global financial crisis a decade ago.

Help can’t come soon enough for Dominik Wilkinson and his co-workers at a restaurant in the northern German town of Bielefeld. The restaurant’s 40 staff members are already working sharply reduced hours, and there’s talk in town of curfews starting Friday. A prolonged closure would be, “death, in terms of revenue. It’s basically the same for every small and medium-sized company,” says Mr. Wilkinson, a shift manager.

[Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.]

In the United States, the past few days have seen automakers mothball factories, hotel chains furlough tens of thousands of workers, and major retailers trim store hours or go online only. A Labor Department report today showed claims for unemployment benefits spiking to 281,000 last week. Every day brings more turmoil in global stock and bond markets as investors seek safe havens, even as central banks cough up amounts not seen since the financial meltdown of 2008.

Yet the situation’s very severity is spurring governments into action. Relief measures range from mortgage or tax holidays to cash infusions for households, while also lending or simply giving money to businesses to prevent mass layoffs or permanent closures.

Analysts say these are precisely the kinds of measures that can help, but their effectiveness will hinge greatly on their magnitude and speed of delivery. And what makes this crisis different, they add, is that a pandemic must also be tamed because the economic and health crises are intertwined.

The Group of Seven international economic organization has already issued a “whatever it takes” statement of determination. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank are mobilizing help for developing nations. But so far it’s an open question whether global leadership today can match the kind of concerted effort that emerged from the depths of the 2008 crisis.

“A lot of people didn’t quite measure the gravity of the situation for a while, including myself to be honest,” says Ioana Marinescu, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “We have to think about supporting business. That’s very important because if we allow businesses to fail, we are losing jobs. ... We’re also losing capital.”

Economic side effects

The top priority remains a pandemic that has killed more than 9,000 people and spread to every continent except Antarctica. Yet, if the economic side effects are left unaddressed, the result would be significant human hardship of another kind. It is costly to rehire workers, let alone to start new businesses from scratch. And the more workers lose jobs and paychecks now, the sharper the downward spiral.

So in the U.S., members of Congress are considering emergency relief for the economy that could surpass $1 trillion in value, of which about half may be cash handouts to families that can be spent as quickly as possible. But in parallel, the Trump administration wants to bail out airlines and other hard-hit industries, and offer loans to help small businesses cope.

Other steps around the world include emergency loans in China and Japan, unemployment benefits for French workers forced into part-time status, and emergency legislation in Britain to halt evictions by landlords during the pandemic.

In Washington, a sense of urgency has blunted partisan edges, at least in part. On Wednesday, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell successfully urged his colleagues to approve a measure, crafted by Democrats in the House, to expand unemployment benefits and paid sick leave, and to make tests for the coronavirus free.

“More than usually, this touches many, many, many actors and not just the most vulnerable. So I think that’s a reason to go broad” with emergency support, says Dr. Marinescu. “It’s like we’re firefighting – first dropping water on the whole building,” then thinking about more targeted relief going forward.

Last week, Germany green-lit a host of fiscal measures to offset the pandemic crunch. Companies large and small can access increased credit, apply for funds to pay idled workers, and seek tax deferrals.

But Katja Sator, owner of a precision engineering company in the southwest state of Baden-Württemberg, worries the emergency aid only amounts to a “mound of debt,” whereas grants wouldn’t weigh down her balance sheet.

“It’s great that we’re receiving help with liquidity and that we can get new credit,” says Ms. Sator, whose company, Frankenstein Präzision GmBH, makes precision parts for automakers and other industries. “But we have to pay everything back. That means it’s not clear whether we’ll be in the red for the year if we have to close down production.”

She hasn’t laid anyone off, but she’s not extending temporary contracts. Her production lines are still running, with technicians spaced 2 meters (6 1/2 feet) apart.

Limits to monetary policy

As markets react to the pandemic, central banks have in many cases acted faster since they are inherently nimbler than legislatures. But unlike in 2008, when the crisis began in an over-leveraged financial sector, the coronavirus has slammed into the real economy, which monetary policy alone is hard-pressed to rescue.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Federal Reserve reopened two programs last used during the global financial crisis a decade ago, to keep the flow of short-term credit from clogging.

And on Wednesday, European Central Bank President Christine LaGarde cited “no limits” to support efforts as the bank launched an $820 billion program to buy government and corporate debt.

For all the actions underway, the question economists raise is what will be enough in these extraordinary times. Forecasting the depth of the slowdown is challenging; recent estimates suggest up to a 14% drop in U.S. economic output (annualized) in the second quarter.

Although the term “fiscal stimulus” often is used for recession-fighting programs, the goal today is really about helping individuals and businesses survive this economic stallout. A rebound will come later. The challenge is to contain the current damage by slowing the spread of COVID-19 while minimizing job losses and firm closures.

“Right now what needs to happen is flattening the curve [of the outbreak] while still doing whatever it takes ... to keep the fabric of the economy and of society alive,” says Fabio Ghironi, an economist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

That means economic rescue should include support for stretched health care systems, he says – something far different from recessions with purely economic causes.

The U.S. and other governments are making some big efforts, but Dr. Ghironi and others argue much more will be needed.

Mangoes for sale

Many less-developed economies face an especially hard time finding the resources for both a public-health crisis and an economic one.

In Mexico City, Julio Bisrreal Alcantaria stands beneath a lush green tree on the sidewalk beside his fruit truck slicing mangoes and papayas. He hasn’t seen much of a slowdown in business due to the coronavirus, he says, but expects nationwide school closures starting this week to hit his business hard.

“I can make it about two weeks with slow sales, and then I’m in trouble,” he says. “If kids aren’t in school and people aren’t going to their offices, I have no one to sell to.”

Mr. Bisrreal is one of the estimated 30 million Mexicans working in the informal economy – without social security or job protections. As with gig economy workers in the U.S., flexibility becomes moot if a pandemic forces people indoors and consumer spending evaporates.

Mexico’s finance ministry has proposed lines of credit, debt refinancing, and helping small businesses stay afloat. But “there’s no real discussion” in the legislature about economic stimulus, says Valeria Moy, an economist at Mexico ¿Como Vamos?, a think tank.

School closings aside, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has resisted an economywide lockdown, arguing that it would hurt poor people. There are “pressures of all types. Close the airport, shut down everything, paralyze the economy. No,” he told a press conference.

Workers scramble for a foothold

Worldwide, the stakes are high. In Odemira, Portugal, Domingos Vicente owns a fruit distribution business with 40 employees, mostly migrants.

“If my business shuts down, I won’t be able to pay them to stay at home not working, and they will not stay around, which means it will be hard to start over again once it’s possible and hire new workers. That means trouble for the agricultural supply in Portugal.”

In Italy, the nation hardest hit in Europe by the virus, the government is helping employers meet their payrolls and freezing loan and mortgage payments for many who are affected by the crisis.

But as in other nations, the emergency programs take time to reach people and may not be enough. That’s especially true for workers in the gig economy like Claudia Bellante, a freelance journalist in Milan. Her husband, a photographer, has seen his work dry up. He’ll be eligible for some emergency grants, but she won’t.

“I understand these are emergency measures for this time, but I worry when the pandemic ends we’re going to be in a very difficult place,” Ms. Bellante says. “I doubt there will be enough money for everyone.”

Dr. Ghironi, the Italian-born economist at the University of Washington, says South Korea has shown how to fight the pandemic without economy-debilitating lockdowns by using prompt testing and infection tracing. Whatever steps work, he says the public-health approach and economic rescue go hand in hand.

“We need the resources and the stimulus to be injected, while the [public health] pieces of the mechanism are put in place, so the lockdown can be lifted as soon as possible.”

Lenora Chu in Berlin, Whitney Eulich in Mexico City, and Catarina Fernandes Martins in Castelo Branco, Portugal, contributed to this article.

[Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. There is no paywall.]

Moral quandary: How to help people without putting them at risk

What if your job means serving the most vulnerable? Groups who care for homeless and elderly people are grappling with how to still help during a pandemic.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

It was a painful moment Friday when Fatime Ba, a volunteer at CityMeals on Wheels, was told she had to forgo her weekly visit with the 96-year-old woman with whom she’s become close. They usually spend at least two hours visiting every Friday.

It’s become one of the ironies of the COVID-19 crisis. In times of national disaster, residents instinctively respond by helping out in overwhelming numbers. People often long to gather, find solidarity and solace in numbers, and a willingness to help those in need.

As the global crisis deepens, social service agencies are facing growing uncertainty, and many programs may need to be curtailed as volunteers and staff members stay home to protect not just themselves, but the vulnerable populations they serve.

CityMeals on Wheels, which delivers meals to 18,000 of New York’s elderly shut-ins, has had to adjust to fewer volunteers and stricter protocols, says executive director Beth Shapiro.

“Friendly visits” are being done via telephone. In addition to hot meals, the service is including nonperishable and shelf stable food. Volunteers who deliver meals follow CDC protocols. “The flip side of this crisis is that New York is this huge city with very often disconnected people, but during times of emergency, it brings us together,” Ms. Shapiro says.

Moral quandary: How to help people without putting them at risk

Like many who serve the homeless, Josiah Haken and the staff at New York City Relief had to scramble last week as they tried to readjust to a world that had suddenly changed.

The faith-based agency relies on its volunteers, Mr. Haken says. For decades the organization has been able to house cadres of volunteer workers from around the country. Most devote a full week to service, staying in the organization’s facility in New Jersey and helping out as the agency’s fleet of relief buses deliver hot soup, socks, and counseling services to five sites throughout New York City.

Last week, their group of volunteers, mostly students from Michigan, cut short their service. And amid the countless disrupted routines of American life, those scheduled to come over the next month have understandably canceled, he says. Most local volunteers, too, are following government guidelines and staying home.

[Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.]

“So we just started to think about what it means for us to go forward,” says Mr. Haken, the vice president of outreach at New York City Relief, which has a paid staff of about 20 people in addition to the volunteers. “You know, how do we follow in the direction of our faith and what our faith leads us to do? And so at the same time, we realized that we need to be smart and wise and careful.”

It’s become one of the ironies of the COVID-19 crisis. In times of national crisis and disaster, residents instinctively respond by helping out in overwhelming numbers. Communities respond to the fears and anxieties surrounding life’s disruptions, people often long to gather, find solidarity and solace in numbers, and a willingness to help those in need.

But now, instead of the laying on of hands, there is the duty to wash hands and stay six feet away. Instead of gathering to comfort and console, the way to help most is to “socially distance,” even during a particularly vulnerable time in our common lives together.

Yet given how closely the relief agency works with people living on the streets, the pandemic is now challenging their very mission, presenting the staff with moral and logistical dilemmas that are, at once, both deeply personal and deeply profound.

“The people who are often forgotten in these kinds of crises are the people who are at the bottom of the economic ladder – people who are homeless are food insecure,” says Mr. Haken. “Yet you have people in the street who are already more likely and prone to have compromised immune systems,” he says. “So what does it mean for us to consider that factor? It’s a lot.”

So far, being smart and wise and careful includes following CDC guidelines, and readjusting their service routines. Workers and remaining volunteers now wear gloves at all times, not just when they serve food, and change them every 15 minutes.

They’ve always washed hands and used hand sanitizer, but now they’re providing stations for their clients to clean their hands. As the lines form for their services, they encourage them to maintain a six feet space between them.

“We’re trying to find that middle ground to achieve our ultimate mission, which is to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, provide the poor wanderer with shelter,” says Mr. Haken, noting how his agency roots its mission in the mandates of Isaiah.

Still, as the global crisis deepens, congregations and social service agencies around the country are facing growing uncertainty, and many programs may need to be curtailed as volunteers and staff members stay home to protect not just themselves, but the vulnerable populations they serve.

Physically distancing, socially communicating

At the New York Society for Ethical Culture in Manhattan, volunteers and staff have had to readjust as well in a time of social distancing.

It’s a term that Elinore Kaplan, a long-time volunteer at the historic humanist congregation, just across the street from Central Park, finds frustrating.

“We may be physically distancing, but we are socially communicating,” says Ms. Kaplan, co-chair of the Society’s communications committee. “I think in every sense, our being a community, our being an ethical family and extended family, we can continue to be present with each other in a variety of ways.”

Most of the society’s staff had already been working from home, but Ms. Kaplan felt a deep need to be present with the few staff members that came in that day, in an office following CDC protocols. As co-chair of the communication’s committee, she’s helping to brainstorm how the society can move forward with its services and other outreach missions.

Its Sunday “platform,” the term they use for their non-theistic but spiritually centered services, has been canceled for the foreseeable future, and committee meetings have moved online or to conference calls.

“We’ve spent the last three days doing nothing but saying, how do we calm people’s fears?” says Liz Singer, president of the Society for Ethical Culture’s board of trustees. “How do we let them know we’re here? How do we let them know that if they feel the need to come in, how can they be able to reach out and to talk to us?”

The society also maintains a women’s homeless shelter in the basement of their building, a partnership with The Olivieri Center in New York. It also houses a televisiting program that connects families with loved ones being held in New York’s notorious Rikers Island jail complex, which houses those awaiting trial and who cannot afford bond.

“We’ve got a lot of people concerned with these outreach programs, asking, ‘Are people getting food? Are we going to be able to continue?’ ” Ms. Singer says.

“This is becoming real now”

It was a painful moment last Friday when Fatime Ba, a volunteer in the “friendly visiting” program at CityMeals on Wheels, was told she had to forgo her weekly visit with the 96-year-old woman with whom she’s become close, and usually spends at least two hours visiting every Friday.

“It took me a minute to realize, wait a minute, this is becoming real now,” Ms. Ba says. “When I call her, you could hear that disappointment in her voice. And she kinda ended up worried, she’s worried, because I don’t know what we’re going to do. But again, it has to be done, because we need to protect ourselves from whatever is happening right now.”

The mission of CityMeals on Wheels, which delivers tens of thousands of meals to 18,000 of New York’s elderly shut ins, has also had to adjust to fewer volunteers and stricter protocols for its services, says executive director Beth Shapiro.

“Many of our meal recipients are already socially distanced,” she says. “They’re isolated, they’re left alone, so even a quick meal coming to the door is connectivity for them.”

The “friendly visits” program, however, is now being done via the telephone. And in addition to the hot meals the agency delivers, the service is now including nonperishable and shelf stable food. Volunteers who deliver these meals follow CDC protocols, sanitizing their hands and maintaining a six foot distance from their clients during deliveries, she says.

Despite seeing fewer volunteers, Ms. Shapiro is witnessing a renewed commitment from those they still rely upon. “The flip side of this crisis is that New York is this huge city with very often disconnected people, but during times of emergency, it brings us together. And I would say, quite frankly, the city feels like a small town in times like these.”

Despite her disappointment at not being able to visit her friend, Ms. Ba is remaining committed to do what she can.

“I started as a volunteer because, when I came in America 20 something years ago, I was received with open arms,” says Ms. Ba, an immigrant from Senegal who now works as a social worker.

“So to me, it’s like giving back to the community,” she continues. “I have found a way to say thank you, thank you for everything that you’ve done for me, for everything that I have now. I have to go back into the community and show my appreciation.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, we’ve removed the paywall for all our coronavirus coverage. It’s free.

A health officer with a fan club? Meet Canada’s Dr. Bonnie.

Not all those in the struggle against COVID-19’s spread are treating the sick. Some, like Dr. Bonnie Henry, are simply telling people what they need to know in a clear and compassionate way.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

There are not many provincial health officers who have fan clubs. But Dr. Bonnie Henry does.

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, British Columbia’s soft-spoken health expert has become beloved in households across Canada. Each day as she addresses the province at 3 p.m. local with the latest data and policy plan – later beamed across the nation in evening broadcasts – she’s become a holder of hands for the Canadian public. With her constant presence and soothing voice, she has mastered a balance between informing a public and keeping it calm.

At a time when it seems politicians have to scream louder and assert their stance to be heard, Dr. Henry – or Dr. Bonnie as people call her – shows that confronting people’s anxieties with honest information is what the public wants.

“From the very beginning, she’s given these daily briefings with very competent science,” says Sally Thorne, a professor of nursing at the University of British Columbia. “One of the real challenges is to help a population of anxious people, when the messages are changing and when there may be naysayers. And she has been just absolutely the epitome of calm and compassion.”

A health officer with a fan club? Meet Canada’s Dr. Bonnie.

Before this month, her name was not widely recognized, let alone her face. But in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, Dr. Bonnie Henry, British Columbia’s soft-spoken provincial health officer, has become beloved in households across the country.

Each day as she addresses the province at 3 p.m. local with the latest data and policy plan – later beamed across the nation in evening broadcasts – she’s become a holder of hands for the Canadian public. With her constant presence and soothing voice, she has mastered a balance between informing a public and keeping it calm, even as she delivers mounting figures and asks for unprecedented community sacrifice.

When she had to announce this month the first death in the province, she nearly teared up, not the first time she’s shown emotion. “What can I say, it’s a very difficult time and I’m feeling for the families and the people dealing with this right now,” she said at one presser, later adding she hoped the media wouldn’t overplay it, so as not to worry her elderly parents. She has made jokes. “Wash your hands like you’ve been chopping jalapenos and you need to change your contacts.”

She has acknowledged people’s fears about the disruption to community life. She told them there’s never been a better time to enjoy the natural beauty around them. “This is our time to be kind, to be calm, and to be safe,” she said.

In response, a “Dr. Bonnie Henry Fan Club” has sprung up on Twitter. There, politicians, business leaders, and plenty of locals heap praise on her style and substance. “Thank you Dr. Bonnie Henry for being a voice of reason, community heart, and communicator of facts,” is one of hundreds of thank you notes. Two women in Vancouver even recorded a tribute to her, adapting the song “Dear Theodosia” from the musical “Hamilton.”

At a time when it seems politicians have to scream louder and assert their stance to be heard, Dr. Henry – or Dr. Bonnie as people call her – shows that confronting people’s anxieties with honest information, as it changes and even reverses, is what the public wants.

“Of all the people shouting, I don’t want to listen to them because they actually inflame the situation. And they make a whole chunk of the population more anxious and less convinced they know what they’re doing,” says Gillian McCormick, a Vancouver physiotherapist who co-hosts a podcast called “Small Conversations for a Better World.” “Meanwhile maybe it’s that quiet woman in the back of the room that’s observed, had a good think, calculated, and went OK.”

Ms. McCormick knew nothing about her provincial health officer before the coronavirus threatened the globe. She certainly wouldn’t have recognized Dr. Henry, with her blond bob and no-nonsense business suits, in a crowd. But with a practice less than a half kilometer from the Lynn Valley Care Centre, the epicenter of the outbreak in British Columbia where six have died, Ms. McCormick has come to depend on Dr. Henry’s steady presence. “As soon as she starts talking, you’re like, ‘Oooh.’ You just feel a sense of calm.”

That, combined with her battle-tested credentials, helps health professionals get their jobs done, says Sally Thorne, a professor of nursing at the University of British Columbia. Dr. Henry has been the provincial health officer for just over two years. She was a leader of the response to the SARS outbreak in Toronto in 2003, and has worked to eradicate polio in Pakistan and control Ebola in Uganda. Perhaps most fittingly, she authored the book “Soap and Water and Common Sense.”

“From the very beginning, she’s given these daily briefings with very competent science,” Dr. Thorne says. “One of the real challenges is to help a population of anxious people, when the messages are changing and when there may be naysayers. And she has been just absolutely the epitome of calm and compassion.”

For the nursing community in British Columbia on the front lines, says Dr. Thorne, she’s helped them to reassure their own patients. “It’s very helpful to have that grounded place, to keep referring people back to substantiate our message to ‘keep calm, we’ve got this, we’re nurses’ message. Yes it’s difficult, but we will get through it.”

She’s been compared to the former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani after 9/11, or New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern after the mosque attack last year. But it may be more suitable to compare her to someone like Ian McDonald, who delivered Ministry of Defense press briefings and became the “unlikely television star of the Falklands War of 1982,” as The Telegraph wrote in his 2019 obituary, with his “matter-of-fact bulletins on the latest developments” that contrasted with “overheated rhetoric” of the time.

Indeed, Jody Vance, a broadcaster in Vancouver, says Dr. Henry has humanized the conflict instead of politicizing it – which inspired Ms. Vance to pen an open letter to her in the independent online publication The Orca.

“Dear Dr. Henry, Can I call you Dr. Bonnie? In our house that’s what we call you. My boy says it’s because he knows you,” she begins.

Whether for her 12-year-old son or the policymakers at the highest levels, it’s the precision and simplicity of her language that has made her so trustworthy.

“She’s very mindful to not use words that in a soundbite could scare people,” says Ms. Vance. “She’s one of those people who makes themselves available to the average Joe and Jane Public to answer the question they’ve been asked a thousand times as if they’ve heard it for the very first time,” she says. “I’ve never met her, but I feel like she’s a family member.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, we’ve removed the paywall for all our coronavirus coverage. It’s free.

Not just for the military: More chaplains come to employees’ aid

How can a diverse workforce, with a changing set of concerns, be best supported? Some point to chaplains, seeing their potential to provide more holistic care and build a more harmonious workplace.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Lee A. Dean Contributor

Jeff has had a lot to deal with. Both his parents as well as his father-in-law died, and he says his daughter has been in an abusive relationship – a situation that has involved court proceedings.

One person who’s helped him is workplace chaplain Jim Emery, who has attended the court hearings. “He knows these things can be very traumatic, so he’s there for moral support,” Jeff says. “His presence is comfort.”

Mr. Emery is one of an estimated 3,500 to 4,000 workplace chaplains in the United States. Though chaplaincy is normally associated with the military or hospitals, private sector chaplaincy has existed for nearly a century – and is enjoying a new wave of growth as companies search for ways to provide more holistic care for a workforce that is increasingly diverse.

Advocates of chaplaincy see wide-ranging benefits to businesses, such as building a more harmonious workplace. Chaplaincy “is a way to build a positive organizational culture,” says Faith Ngunjiri, director of the Lorentzsen Center for Faith and Work at Concordia College. “We like to say chaplaincy is an ecumenical employee care service.”

Not just for the military: More chaplains come to employees’ aid

On a chilly morning at a publishing company here, chaplain Jim Emery begins to make his rounds. He starts with the IT department, but he doesn’t get far before an employee stops to thank him for help he gave to a family member. In the back shop by one of the printing presses, Mr. Emery asks workers about their family members, and in return they ask about his.

On other days at this company, Mr. Emery holds one-on-one meetings with employees. In those confidential conversations he helps workers deal with some of life’s toughest challenges.

“I love talking to people. ‘Who are you? Tell me about your kids. How long have you been married?’” Mr. Emery says.

Chaplaincy is normally associated with the military (think Father Mulcahy on “M.A.S.H.”) or with hospitals. Private sector chaplaincy has existed for nearly a century, but is enjoying a new wave of growth as companies search for ways to provide more holistic care for a workforce that is increasingly diverse.

Advocates of chaplaincy say its benefits to businesses include building a more harmonious workplace, helping to reduce turnover and absenteeism, and improving productivity due to increased worker well-being.

Chaplaincy “is a way to build a positive organizational culture,” says Faith Ngunjiri, director of the Lorentzsen Center for Faith and Work at Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota. “When you listen to business leaders who are very invested in chaplaincy, the motivation is not, ‘Let’s take care of the spiritual needs.’ It’s more like, ‘Let’s take care of the needs of our employees, whatever they might be.’”

The total number of workplace chaplains in the United States is between 3,500 and 4,000, Dr. Ngunjiri estimates. Marketplace Chaplains, one of the largest chaplaincy providers in the U.S., serves approximately 250,000 employees and 1,000 companies.

“We’re getting more leads, more contacts, and more calls than we can process,” says Doug Fagerstrom, executive president and CEO of Marketplace Chaplains, who notes that his organization is growing about 15% to 20% a year.

Mr. Emery was one of the first to join the new wave of chaplaincy. He was planning on a quieter life after years working on church pastoral staffs and as a teacher. Then, in 2006, he was contacted by Marketplace Chaplains.

“They said they wanted me to be a chaplain. I said, ‘Are you kidding? I’m 70 years old and I don’t want to punch a clock,’” Mr. Emery says.

“And he’s been punching one ever since,” says Greg Boisture, executive director of operations for the Michigan division of Marketplace Chaplains.

Mr. Emery, now in his 80s, says he decided to take the plunge because chaplaincy fit into his skill set. “If I were going to be reincarnated, I’d come back and work with families,” he says.

“His presence is comfort”

One person Mr. Emery has assisted is Jeff (whose last name is being withheld due to confidentiality). Not only has Jeff dealt with the deaths of his parents and father-in-law, but he’s also discussed his daughter being in an abusive relationship. That situation has involved court proceedings.

“Though he’s not required to be there, Jim will show up at the hearings,” Jeff says. “He knows these things can be very traumatic, so he’s there for moral support. His presence is comfort.”

Mr. Emery has also organized a small group to help young men successfully make the transition from the educational system to the workplace. And he’s working to form a group for single parents.

“We work with human resources departments to make sure we’re meeting the needs of their staff,” says Mr. Boisture.

Noordyk Business Equipment in Grand Rapids has used chaplains for three years. Owner Bill Noordyk believes the chaplains help provide an outlet for his employees to express concerns and needs that they may not be able to bring directly to him.

“The chaplain can say things to the employee that I as the business owner probably can’t,” Mr. Noordyk says.

One chaplain visiting the business learned that an employee’s marriage was in danger of falling apart. The chaplain kept meeting with the employee and eventually referred him to a faith-based counselor. Though all these conversations were confidential, the employee eventually confided in Mr. Noordyk after the crisis had passed.

“He came into my office and said that he had been married a long time but that his marriage had never been stronger. To have an employee come up and share that with me ... I’m welling up just thinking about it,” says Mr. Noordyk. “You can’t put a price tag on that. If we ever had to make budget cuts or changes, there’s a thousand other things that will go before this program ever goes.”

“Ecumenical employee care”

Chaplains with organizations such as Marketplace Chaplains don’t hide their religious allegiance but do not proselytize.

“We like to say chaplaincy is an ecumenical employee care service,” says Dr. Ngunjiri at Concordia College. “We say it’s ecumenical from the get-go, because if somebody does not have that perspective, it would be very difficult for employees today because of all their allegiance diversities.”

Mr. Emery, a Baptist, says he has provided care to married same-sex couples with foster children, Muslims, Hindus, and those with no religious affiliation. He recalls an exchange with a Muslim employee from Kenya at a holiday gathering. “His family had just had a baby, and that opened up a whole new area of conversation. Every week, I would ask about the baby. So at the gathering, he met my wife and I at the coffee bar. I introduced her; he shook her hand and said, ‘I love your husband because he actually talks to me.’”

Despite the growth of workplace chaplaincy, only a sliver of U.S. companies use the service, and Mr. Fagerstrom estimates less than 1% of the nation’s workforce benefits. Chaplaincy providers must overcome objections from both labor and management. Despite the promise of confidentiality, workers can still be wary that chaplains will share their conversations with management.

“It takes six to nine months for people to start opening up,” Mr. Boisture says. “The company says it’s not working and I say, ‘Yes, it is. You have to give it time.’”

Introducing religion and spirituality into the workplace is another roadblock for some companies. In a volatile political environment, companies may be reluctant to add another potential hot-button topic. This reluctance is one reason chaplains are sometimes called “care providers” as a way to soften the religious connotation.

An additional objection is the perception that existing human resources and employee assistance programs are sufficient and that chaplains represent a superfluous layer of care.

Many chaplains, such as Mr. Emery, are retired pastors or former church staff members. Others are active ordained clergy. Laypersons are also a significant portion of the chaplaincy ranks. Marketplace Chaplains provides training for all its recruits before their initial assignments and then provides ongoing training.

“Chaplains don’t need to be seminary-trained,” says Mr. Fagerstrom. “Sometimes, seminary-trained people don’t make the best chaplains because we don’t want them to just be ‘answer’ people. What’s important is that they can help people navigate through their lives.”

On Film

Feel-good flicks to watch at home while social distancing

In times of uncertainty, we value a good laugh. Film critic Peter Rainer recommends a selection of his favorite feel-good choices to help. “Movies can transport you just about anywhere,” he says, “and these days, more than ever, we all crave a safe harbor.”

-

By Peter Rainer Film critic

Feel-good flicks to watch at home while social distancing

“There is no Frigate like a Book,” wrote Emily Dickinson, but that was before movies were invented. Movies can transport you just about anywhere, and these days, more than ever, we all crave a safe harbor. I can’t think of many better ways to boost the spirits than by watching wonderful movies that make us feel good all over. I’ll kick things off with three of my favorites, all readily accessible for home viewing, in what I hope will become an ongoing column of pandemic picker-uppers.

[Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.]

“Some Like It Hot”

Let’s start with “Some Like It Hot” the classic 1959 Billy Wilder comedy, co-written with his frequent collaborator I.A.L. Diamond, and starring Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in top comedic form. They play Joe and Jerry, low-rent Chicago jazz musicians who witness a gangland shootout and, fearing mob retaliation, flee, in drag, to Miami with an all-girl band. Gender confusions abound. “Daphne” (Lemmon), despite her rebuffs, is wooed by millionaire playboy Osgood Fielding III (the great Joe E. Brown, with his mile-wide smile). “Josephine” (Curtis), adopting a second disguise as “Junior,” the Shell Oil heir, falls for Marilyn Monroe’s Sugar Kane Kowalczyk, the band’s singer and ukulele player. The plot thickens when the mob boss who engineered the Chicago massacre, George Raft’s “Spats” Colombo, checks into the same Miami hotel for a gangland summit.

If you’ve never seen this movie before, I truly envy you. It’s one of the funniest films ever made – maybe THE funniest. And if you’ve seen it more than a dozen times, as I have, rest assured it remains as hilarious as it was the first time. That’s partly because, knowing what’s coming, we can savor the best moments when they arrive on schedule. As Junior, Curtis sports a note-perfect Cary Grant accent. Lemmon, one of the rare actors who could play high comedy and serious drama with equal conviction, has never been more giddy than in the scene where he dances the tango with Osgood until dawn. Soon after, he announces to a stunned Joe that he and Osgood are engaged.

Monroe is also at her dreamy comedic peak here. Whatever diva difficulties Wilder may reportedly have had directing her on set (which was actually the famed beachside Hotel del Coronado near San Diego), nothing of that shows up in the film.

As seen through the eyes of Joe and Jerry, “Some Like It Hot” really plays up the ways in which men can be flabbergasted by women, with how they look and talk and move. The plot, especially for 1959, may be risqué but the tone throughout is heedlessly innocent. And, of course, with the possible exception of “Casablanca,” it boasts the best closing line in all of movies. I’ll resist – just barely – the impulse to give it away. (Rated PG)

“Steamboat Bill, Jr.”

If you, or any children you know, have never experienced the great Buster Keaton, there is no better place to start than “Steamboat Bill, Jr.,” the 1928 film he co-directed with Charles Reisner. Keaton, whose trademark deadpan was actually quite expressive – look closely! – plays the citified college graduate son of a tough-as-nails Mississippi steamboat owner (hulking Ernest Torrence). Dad disapproves of his son’s foppish ways, but Junior proves himself the better man in an astonishing whirlwind storm sequence at the end. Its most famous gag, shot without a stunt double, has the façade of a house falling over Keaton, framing him in the rectangle of a window. Don’t try this at home – or anywhere else. If this film gives you a hearty appetite for more Keaton, try “The General,” “The Navigator,” “Sherlock Jr.,” and “Seven Chances.” All masterpieces. (Unrated)

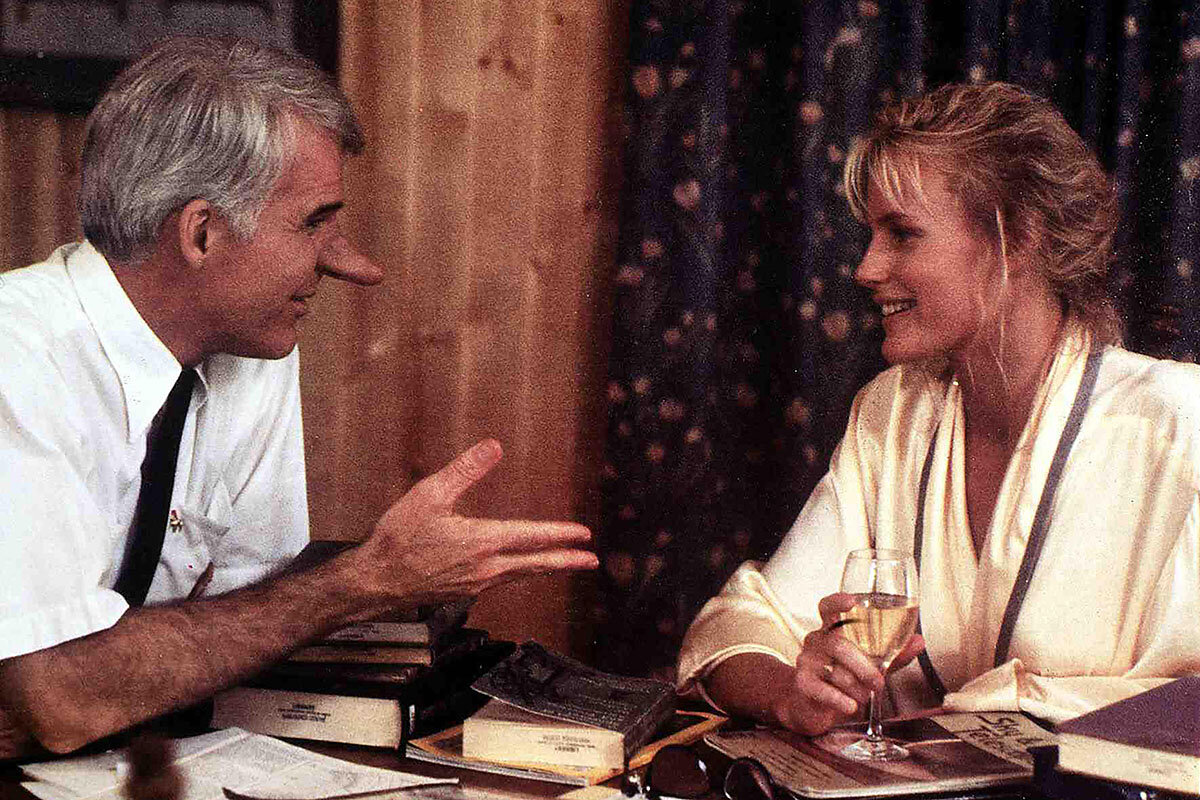

“Roxanne”

The actor who learned the most from Keaton about physical comedy was Steve Martin. He is at his peak in Fred Schepisi’s 1987 “Roxanne,” the “Cyrano de Bergerac” update that he also wrote. He plays C.D. Bales, the long-nosed fire chief in a Washington off-season ski resort town who pines for Roxanne (Daryl Hannah), a starry-eyed astronomy student. When the film was first released, I wrote that it was one of the most elating romantic comedies ever made in this country. I still feel that way. It makes you feel unreasonably happy, as if you were watching colors being added to a sunset. (Rated PG)

I wish you all happy viewing.

These films are available for rent from Amazon’s Prime Video, YouTube, and Google Play. “Some Like It Hot” also airs on the Turner Classic Movies (TCM) network on March 25, and is leaving Prime on March 31.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The unhailed progress for women in politics

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

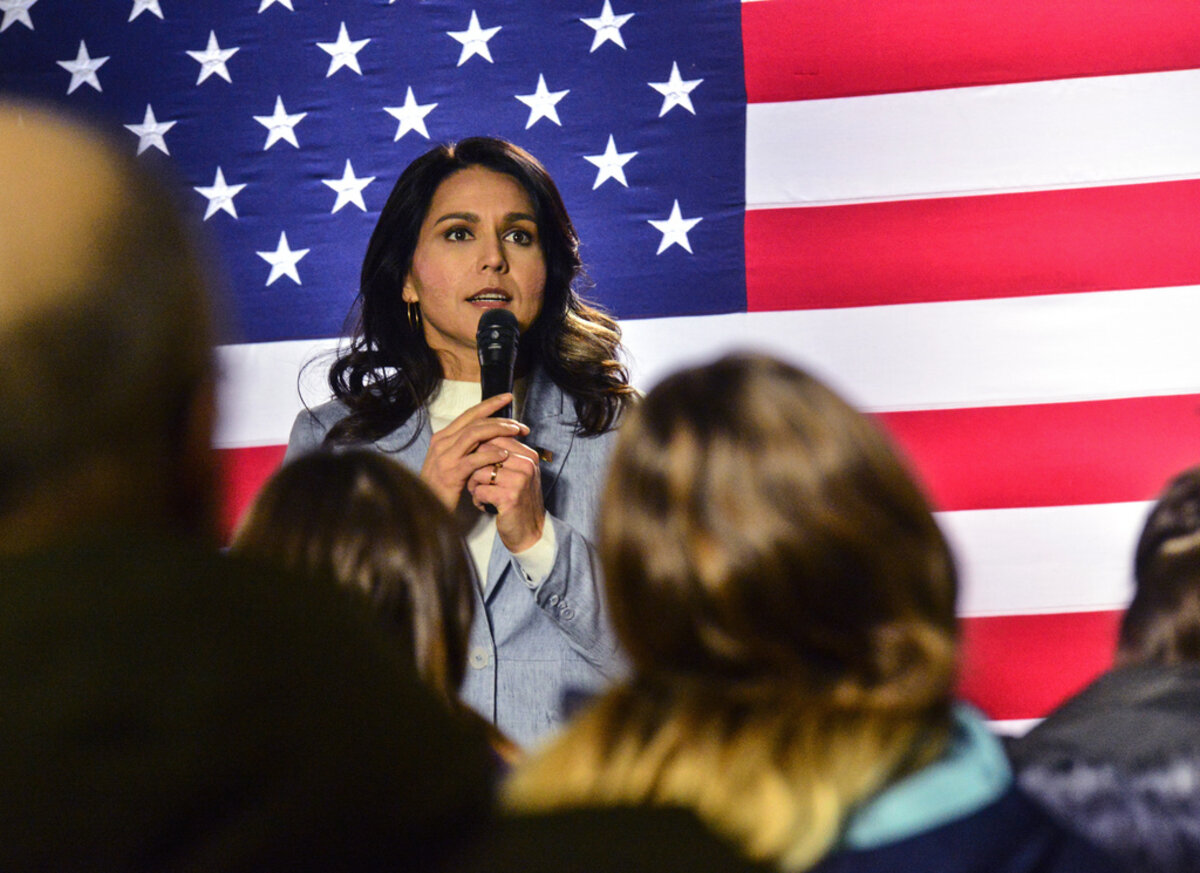

On Thursday, when Tulsi Gabbard became the last female candidate to drop out of the race for the Democratic presidential nomination, it confirmed to many that women had hit a glass ceiling at the polling booths. Were primary voters concerned that a woman couldn’t defeat President Donald Trump? Or was the slate of women candidates just not good enough to be president?

The picture for women dramatically changed again March 15 when former Vice President Joe Biden pledged to select a woman as his running mate. Since Mr. Biden speaks of himself as a “bridge” president who would most likely serve only one term, if he is elected his running mate would suddenly be in a strong position to win the 2024 Democratic nomination.

Mr. Biden could easily find a qualified candidate for vice president. The abundance of choices is the result of a continuing surge in the number of women holding public office.

The current times need leaders with qualities sometimes more identified as feminine (compassion, empathy) just as much as courage or strength are required. The good news is that officeholders of both genders have the opportunity to express all of these qualities.

The unhailed progress for women in politics

What a difference a few weeks makes. No, not because of the worldwide health crisis. Rather America’s political map has changed quickly too.

On Thursday, when Tulsi Gabbard became the last female candidate to drop out of the race for the Democratic presidential nomination, it confirmed to many that women had hit a glass ceiling at the polling booths. Were primary voters concerned that a woman couldn’t defeat President Donald Trump, even though Hillary Clinton won the popular vote in the 2016 election? Or was the slate of women candidates just not good enough to be president?

The picture for women dramatically changed again March 15 when former Vice President Joe Biden pledged to select a woman as his running mate. Since Mr. Biden speaks of himself as a “bridge” president who would most likely serve only one term, if he is elected his running mate would suddenly be in a strong position to win the 2024 Democratic nomination.

Sens. Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar, Kamala Harris, and other women presidential candidates have already introduced themselves to voters. But Mr. Biden could easily find a qualified candidate for vice president elsewhere, among governors such as Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer or even among U.S. representatives, such as Val Demings of Florida, who gained visibility as a manager at the impeachment hearings.

The abundance of choices is the result of a continuing surge in the number of women holding public office. A record 26 women serve among the 100 U.S. senators (17 Democrats, 9 Republicans). The U.S. House of Representatives (435 members) includes 101 women (88 Democrats, 13 Republicans), just below the record of 102. And nine women (6 Democrats, 3 Republicans) sit in state houses among the 50 governors, tying the record high.

Farther down the political ladder, roughly 2,145 women now serve in the 50 state legislatures, 29% of the total members, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. That’s up from 25.3% in 2018. In Nevada, women hold a majority of seats in the state legislature, and they come close in Colorado (47%).

Women in public office should be such a common and unremarkable thing that the topic rarely deserves a thought or mention. That doesn’t necessarily mean some kind of numerical quota is reached, but rather a widespread sense that gender no longer plays a role in the voting booth. Movement on the path to that future will receive a strong boost when a woman is finally elected to the nation’s highest office.

The current times need leaders with qualities sometimes more identified as feminine (compassion, empathy) just as much as courage or strength are required. The good news is that officeholders of both genders have the opportunity to express all of these qualities.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Go deeper for refuge

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Lindsey Roder

If we feel tossed around by uncertainty or unhappiness, we can open our hearts to God’s limitless love, which brings comfort, peace, and healing.

Go deeper for refuge

When I was first married, my husband was an officer on a boomer, one of the largest submarines in the world. One time, the submarine got caught in a storm, tossed to and fro by relentless waves. Many of the men became sick, and it was apparent the sub needed to get out of the storm. It did this by diving deeper – for refuge. Once a submarine is submerged, it uses its sonar or “active” listening.

I like to think of this as a good scenario for prayer, too. When we feel as though we are being tossed around in feelings of sickness or sorrow, we have an opportunity to go deeper for refuge. Right when life seems uncertain, we can go to God, who is Spirit, to learn more about our real identity as a spiritual idea of God.

The first step in recognizing what we really are is to go deeper than mere physicality or superficial personality traits, and to actively listen to what God is saying. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, gives this comforting counsel: “We must look deep into realism instead of accepting only the outward sense of things” (p. 129). In this way we discern the spiritual reality of God’s goodness, expressed throughout creation.

A few years ago, I was struggling with feelings of grief over the loss of a loved one. I felt overwhelmed and had a hard time coping with what felt like the “new normal.”

Realizing that I couldn’t continue on this path, I decided to deepen my understanding of God and my relation to Him as a beloved child. I reached out in heartfelt prayer, and soon felt enveloped by God’s tender love and care for my family and me. This love didn’t feel shallow or changeable. God’s love felt like a great deep welling up from within, bringing needed peace.

In several places, the Bible talks about finding refuge in God, and we can all do that. Quoting one of those Bible promises, the opening verse of Psalm 46, Mrs. Eddy says, “Step by step will those who trust Him find that ‘God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble’” (Science and Health, p. 444). Whatever storms we encounter, we can always go deeper in our understanding of God, divine Love, for refuge.

Adapted from the Feb. 7, 2020, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

When every living room is a newsroom

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: Ann Scott Tyson is working on a profile of Seattle’s Mayor Jenny Durkan, who has taken a collaborative, can-do approach to helping her community and combating the coronavirus.