- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

From museums to postcards, getting creative to keep people employed

Today, we look at online education as more than a stopgap, the Kentucky governor’s new fanbase, family “porchraits,” why we hoard toilet paper, and points of progress around the globe.

First, some thoughts on employment and creativity.

The March jobless rate – out today at 4.4% – doesn’t capture the real state of the labor market, because of survey lag. More likely, The New York Times estimates, unemployment is closer to 13%. We won’t sugar coat; that’s a gut punch.

Congress’s $2 trillion economic rescue package will bring relief to some. But around the country, people are thinking creatively about how they can employ others. In Kansas City, Missouri, the National WWI Museum and Memorial has avoided layoffs by putting 10 of its employees on a project digitizing thousands of old letters, photos, and journals.

Here in Washington, D.C., a local activism incubator and retailer called The Outrage is hiring unemployed people for $15 an hour to handwrite postcards on behalf of others. The recipients are friends, relatives, even love interests who would appreciate a little note of encouragement or humor. A couple who had to cancel their wedding enlisted the service, called The Outrage Postcard Project, to send cards to everyone on their guest list. Customers choose how much to spend, starting at $3 a card.

“We don’t manufacture things, so I can’t make masks,” Rebecca Lee Funk, founder of The Outrage, told the DCist local news site. “But I could probably make some people smile, and give some people some work.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How online learning may be more than a stopgap in the US

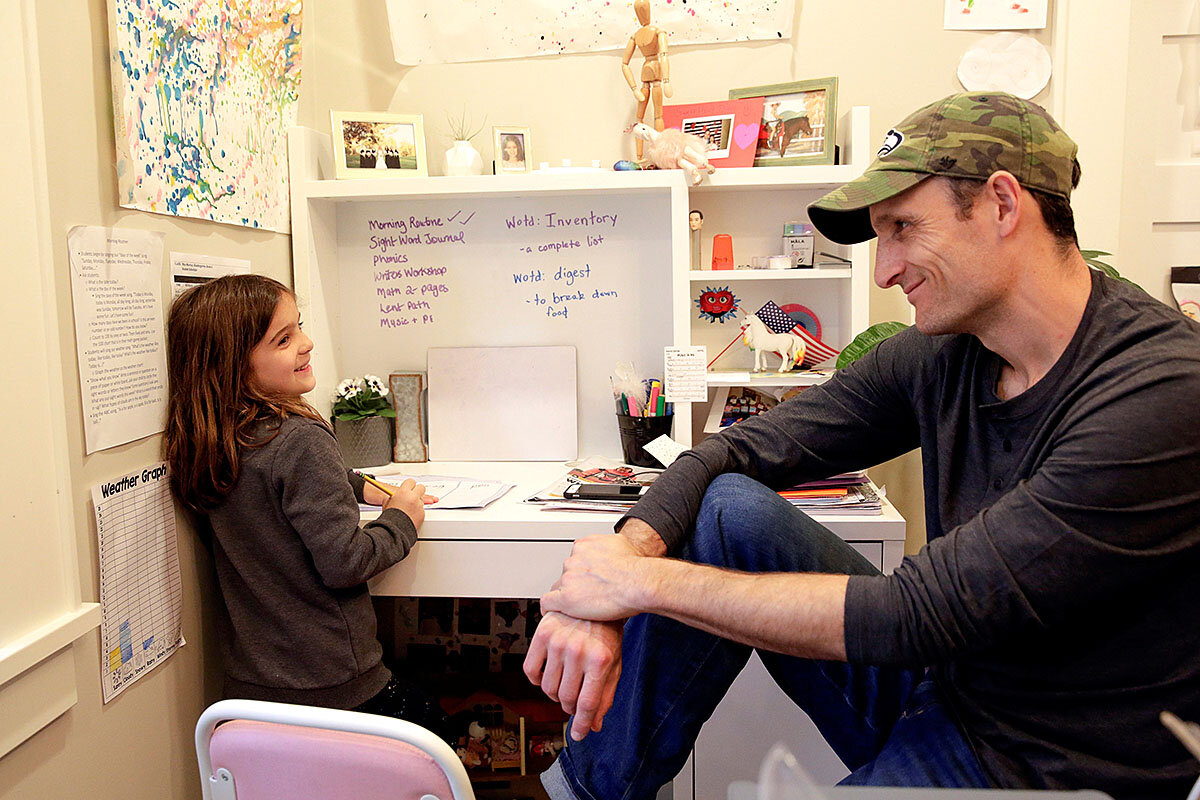

What changes to the way children are educated might come after the current pandemic? While there are still shortcomings to address, some see innovation happening in online learning – and in how people think about the goal of education.

Over the past weeks, students and teachers have jumped into all varieties of virtual education, from Google classroom videos to Zoom lectures to virtual field trips. Some see it as just scratching the surface of what can be accomplished using technology with teaching.

It is but one of the impacts that the coronavirus pandemic is having – and may continue to have – on the education system. With at least 55.1 million students out of school in the U.S. as of April 2, the outcomes of prolonged absence from a classroom are increasingly being considered.

The shortcomings of online learning and the advantages of in-person learning, like socialization, are being raised. But there is a shared sense that innovation and creativity around the delivery of learning are being explored at this time – along with deeper thinking about motives.

“There’s no way you can get through an experience like this without some sort of impact,” says Vicki Zakrzewski, education director at the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley. “I wonder if it won’t change how we view the purpose of education. In the West it’s been about academics. How to survive in a global marketplace. This is making us step back and question what is important.”

How online learning may be more than a stopgap in the US

Jessica Calarco has been thinking a lot recently about the importance of school.

This isn’t just because the sociology professor has been learning firsthand, like so many millions of other parents around the country, how life works without school. (For her, it involves new locks on the office door to keep her 5- and 2-year old from interrupting the Indiana University classes she is now teaching by Zoom.)

No, for Professor Calarco, the new life of trying to get a preschooler to do worksheets while a toddler runs amok in the background has brought up a host of concerns about what this unprecedented moment in American education might mean long term – particularly for disadvantaged students.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Professor Calarco studies inequity in education. Recently, she published a paper on the difference in homework expectations for low-income families. So she worries about increasing educational disparity as tens of millions of students bring all of their work home, for an unknown length of time.

“Homework-related inequalities become even more consequential now that schooling has basically all been pushed home,” she says.

Professor Calarco is far from the only one thinking about the long-term impact of the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on the education system. As of April 2, at least 55.1 million students were out of school in the U.S., according to Education Week, which has been keeping a running tally of school closings. At least 124,000 schools have been impacted by the coronavirus crisis, according to their count – nearly all of the 98,000 public and 34,000 private schools that exist in the country, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

“There’s no way you can get through an experience like this without some sort of impact,” says Vicki Zakrzewski, education director at the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley. “I wonder if it won’t change how we view the purpose of education. In the West it’s been about academics. How to survive in a global marketplace. This is making us step back and question what is important.”

At this point, the predictions are theoretical. As Michael Hansen, senior fellow and the director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution, says, a lot depends on whether schools and families treat this moment like an extended snow storm – a monthlong closure after which everything goes back to normal – or a fundamental shift.

But he and others say that, at the very least, the experience in online learning for millions of students will change the way schools approach virtual education.

“There has been an overall resistance to technology [in schools],” Mr. Hansen says. “I do believe this will be something that will motivate more schools and districts and states to take the virtual learning environment and classroom much more seriously.”

Indeed, over the past weeks, students and teachers have jumped into all varieties of virtual education, from Google classroom videos to Zoom lectures to virtual field trips. But as Jennifer Mathes, interim chief executive officer for the nonprofit Online Learning Consortium, says, many educators are just scratching the technological surface.

“What we’re seeing right now doesn’t fully reflect what online can do,” she says. She expects that as educators continue teaching remotely – and even after they come back to the physical classroom – they will likely delve into a more concerted and sophisticated exploration of how to embrace online learning.

“I don’t think anyone ever saw something like this happening on this scale,” she says. “But it could happen again. We’re going to have to be prepared to shift into online learning and do it in a way that is effective.”

While Mr. Hansen says he doubts that the online classroom will replace much elementary education – just check out the memes posted by parents trying to work at home while managing their second graders’ internet-based lessons – he sees a potential for virtual education to affect older grades. High school, for instance, has long puzzled educational reformers, resisting the achievement gains enjoyed over the past decade by younger students. Perhaps, he says, online learning could be used for innovation in these older grades.

“I wouldn’t be surprised to see more and more states requiring one or two virtual classes in high school,” he says.

But as Professor Calarco points out, there are issues with any large movement to online education. There is still a large digital divide in the U.S. According to the Pew Research Center’s analysis of 2015 U.S. census data, nearly a third of lower income school-age children lack access to high-speed internet. Those same children are least likely to have parents with the time and resources to give extra academic help, Professor Calarco says.

This is part of the reason why Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, believes the pandemic will push schools in the opposite direction.

“People thought, ‘Online. It’s going to replace teaching and learning.’ Nope. Now people are seeing all the negatives,” she says. “What you’re seeing is the limitation of remote learning and online learning.”

In her view, the pandemic may well remind people of the importance of school. Beyond academics, schools can serve communities as a source of food for lower income students, counseling, and the arts. Teachers may also be able to do their jobs more creatively, she says. The federal government has lifted requirements for standardized testing; teachers now have more independence to create the best curriculum possible for their students.

“People are starting to appreciate again the bricks-and-mortar schools; what they mean for socialization, relationship building,” Ms. Weingarten says.

Claire Leheny, executive director of the Association of Independent Schools in New England, is also thinking about relationships.

“How do you keep community at this moment?” she says. “What does community mean when we don’t congregate? How do you keep community in a virtual world? Our leaders are grappling with that.”

She, too, is noticing a new sort of innovation and imagination within the education landscape. School leaders, even at the most rigorous schools in the country, are recognizing that they simply won’t be able to teach 100% of the intended curricular material – and some are starting to wonder whether that’s OK, whether the volume of content itself is less important than the underlying skills. The traditional approach of “synchronized learning,” where students are learning together at the same time, is shifting to individual learning. And teachers who have never taught virtually are experimenting with and creating innovative platforms – often doing so in amazing, new ways, she says.

“People ask, ‘What are the things we need to do to keep learning and curiosity alive, but not necessarily have to deliver curricular content in exactly the same way, or in the same volume or quantity,’” she says. “This is a moment that demands learning by our educators … and I’ve got to say, educators like learning.”

Ms. Leheny sees it as inevitable that schools will have to grow and change from this pandemic. So does Ms. Zakrzewski, from the Greater Good Science Center. Her program recently launched the “Greater Good in Education” site, which shares research-based practices in social-emotional learning and character development, among other topics.

“Kids eventually will be going back to school,” she says. “There will be some processing that needs to happen with these children, and with the teachers. What just happened? What did we just live through? It’s not just about the academic tasks anymore. This idea of shared humanity is coming out as a theme. What kind of world do we want to live in?”

Stepping Up

In Kentucky, a Democratic governor gains new fans: Republicans

As they confront a pandemic, governors are seeing their popularity soar. Kentucky’s Andy Beshear is winning plaudits for a calm, pragmatic approach that some see as a model for bridging the partisan divide.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Every evening, he begins the same way. “We will get through this,” says Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear shortly after taking the podium. “And we will get through this together.”

Governor Beshear may not be speaking from one of the nation’s COVID-19 “hot spots,” but his nightly 5 p.m. press briefings have become a reassuring ritual for the Bluegrass State, with more than a dozen self-identified conservative Kentuckians interviewed by the Monitor offering unabashed praise for their Democratic governor. He presents practical advice, such as how to explain the current situation to children, as well as new executive orders, such as pausing housing evictions and expanding unemployment eligibility.

Most important, say his conservative supporters, Mr. Beshear is staying true to the “together” part of his opening statement by avoiding partisan language and blame shifting. Just a few months after beating an unpopular incumbent governor, Mr. Beshear is proving it’s possible to effectively communicate with both Republicans and Democrats during a crisis.

“He has given me hope that we can turn this around,” says Dominique Dye, a stay-at-home mom from Lexington who did not vote for Mr. Beshear but is now a vocal fan. “Both the coronavirus and our country’s polarization.”

In Kentucky, a Democratic governor gains new fans: Republicans

Every evening, he begins the same way. “We will get through this,” says Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear shortly after taking the podium. “And we will get through this together.”

No state has been spared from COVID-19, and while Governor Beshear may not be speaking from one of the nation’s “hot spots,” his nightly 5 p.m. briefings have become a reassuring ritual for Kentuckians. Mothers pause their dinner preparation to turn up the TV’s volume, and 20-somethings tune in to online watch parties.

Members of both parties in the Bluegrass State say Mr. Beshear’s daily briefings are a comforting antidote to these anxious times, with more than a dozen self-identified conservative Kentuckians interviewed by the Monitor offering unabashed praise for their Democratic governor. Dominique Dye, a stay-at-home mom from Lexington who voted for Mr. Beshear’s Republican opponent just four months ago, has found herself creating and sharing memes in a pro-Beshear Facebook group of more than 180,000. Some of the governor’s most popular phrases from his briefings are even being marketed on T-shirts and mugs, with proceeds going to the state’s COVID-19 relief funds.

He isn’t the only governor enjoying a surge in popularity right now. A recent national poll found strong bipartisan support for state executives, with almost 75% of Americans approving of their governor’s handling of the crisis. Republican Govs. Mike DeWine of Ohio and Larry Hogan of Maryland have won widespread praise for taking decisive action early. Some governors have hit record approval ratings, such as New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, whose daily briefings have made him something of a national star. Mr. Beshear’s audience is far smaller than Governor Cuomo’s, but his fans appear equally ardent.

Editor’s note: As a public service, we’ve removed the paywall for all our coronavirus coverage. It’s free.

Every night the newly elected governor updates his state calmly and confidently, but without fear-mongering, many Kentuckians say. He presents both practical advice, such as how to explain the current situation to children, as well as the state’s detailed containment plan. He announces new executive orders to make daily life easier, such as pausing all housing evictions and expanding unemployment eligibility.

Most important, say his conservative supporters, Mr. Beshear is staying true to the “together” part of his opening statement by avoiding partisan language and blame shifting. Like other U.S. governors elected in states that lean to the opposing party, Mr. Beshear campaigned as a moderate who would reach across the aisle. But locals say he’s done more than that, just a few months after barely beating a widely unpopular incumbent governor. He’s proving it’s possible to effectively communicate with both Republicans and Democrats during a crisis.

“He has given me hope that we can turn this around,” says Ms. Dye. “Both the coronavirus and our country’s polarization.”

Ms. Dye says she’s never voted for a Democrat before, but if Mr. Beshear runs for reelection in 2024, she will not only vote for him, she will volunteer for his campaign. Her mother, Deborah Dye, vowed she would never vote for a Democrat after seeing how the party treated President Donald Trump – but says she’ll break that promise for Mr. Beshear.

“He’s doing what I wish all politicians would do, which is set aside the politics of it and focus on what’s good for the country,” says Deborah Dye.

When reporters try to “bait” Mr. Beshear with questions about the federal response, or other states, he typically redirects the conversation. After President Trump said last week that he would like the country back up and running by Easter, for example, Mr. Beshear was asked during his daily press conference if he considered the president’s statement “realistic.” The governor didn’t reference the president in his answer, instead saying that Americans need to be prepared to sacrifice more and wait longer to protect one another.

“I just hear a lot of Trump bashing around this,” says Cathy Samuels, a registered nurse from Louisville, who voted for President Trump in 2016 and plans to vote for him again in November. She didn’t vote for Mr. Beshear, and if the election was held again tomorrow, she’s not sure she would change her vote. But for now, she appreciates how Mr. Beshear seems to be looking out for all of Kentucky, not just his own party. “I appreciate the fact that Beshear is not politicking this right now.”

“I’m starting to question whether he’s a Democrat or not,” says Ms. Dye, laughing. “I’m even starting to question if he’s a politician – and I love that.”

Of course, not everyone in Kentucky is happy with how their governor is handling things.

Similar to the partisan debate happening at the national level, some Kentucky conservatives believe the governor’s efforts to fight the pandemic have gone too far, unnecessarily hurting the economy. On March 19, a Republican legislator filed an amendment to a bill in the Kentucky state house allowing residents to sue the state if an executive order adversely affects their business. And Mr. Beshear has drawn criticism from the left, with some environmental advocates accusing the governor of using COVID-19 as a smokescreen to sign a new law criminalizing fossil fuel protests.

But his ability to communicate without “coded” language could offer a lesson for other politicians, says Stephen Voss, an associate professor of politics at the University of Kentucky. Instead of talking about the essential role of government in protecting public health, for example, Mr. Beshear is talking about the essential role of community. The governor’s daily briefings have become “the social media version of FDR’s fireside chats,” says Mr. Voss, blending comfort with competence.

“The lesson here is that in a crisis of this sort, where people are fearful, they don’t look at the government the same way they do under normal circumstances,” says Mr. Voss. “It’s not about ideology right now.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, we’ve removed the paywall for all our coronavirus coverage. It’s free.

Say cheese! Families commemorate isolation with ‘porchraits’

One of the surprising ironies of the social distancing era is that this time of isolation is fostering other kinds of togetherness. Canadian photographers are capturing that duality with “porchraits.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

A new phenomenon is sweeping the photography community in Canada: “porchraits.” These family portraits, often taken on porches, are one way of marking the physical isolation that many are feeling right now. But they also highlight a renewed embrace of togetherness felt by many families.

“People are together in a way they haven’t been in a long time,” says Erik McRitchie, a brand photographer in Calgary, Alberta.

Mr. McRitchie is part of a network of photographers using the hashtag #porchraits to inspire one another to get out and document their communities. Many of the images are whimsical, poking fun where they can. One family poses on their porch with rolls of toilet paper around their wrists. Other photos are more stark, revealing the stillness and solitude of the social distance era.

By sharing these images on social media, Mr. McRitchie hopes his work can serve as a buoy for others stuck at home. “When we see people are celebrating, laughing and having fun, and families that are together,” he says, “it's reminding us of the strength we can find together.”

Say cheese! Families commemorate isolation with ‘porchraits’

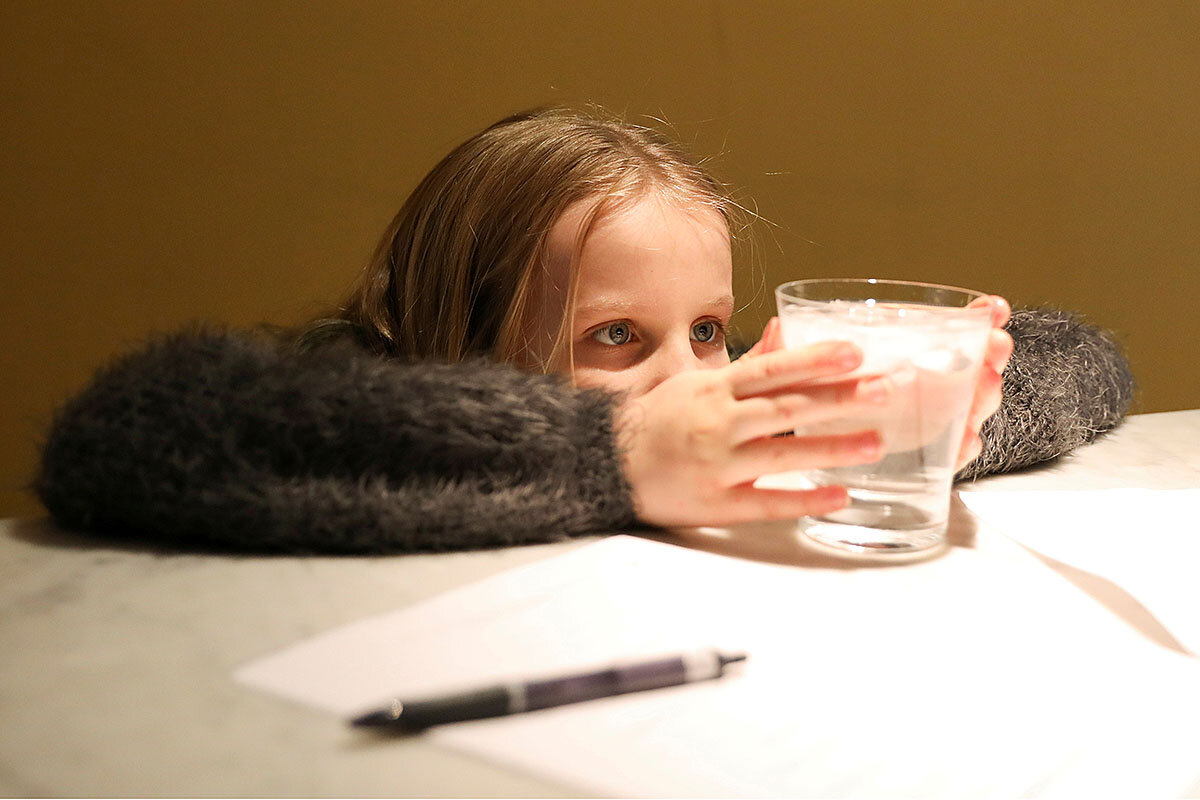

The children’s hands push into the glass pane as the family of five poses behind their front door. In some photos, family members peer over their fences, only their eyes visible. Many of the portraits play on space and distance – each member hangs a head out of a separate second-story window, for example.

Welcome to a new phenomenon sweeping the photography community in Canada: “porchraits.” These family portraits, often taken on porches, are one way of marking the physical isolation that many are feeling right now. But they also highlight a renewed embrace of togetherness felt by many families.

“We’re living through a unique period of time for all of us,” says Erik McRitchie, a brand photographer in Calgary, Alberta. “People are together in a way they haven’t been in a long time.”

That’s something families are keen to hold onto, judging by Mr. McRitchie’s busy calendar. At the middle of last week he had done 25 shoots and had 40 more to go.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Mr. McRitchie is part of a network of photographers inspired by one in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, who started taking photos of residents through their windows. Using the hashtag #porchraits, photographers have inspired one another to get out and document their communities. And the practice has started to pop up in the United States; though there’s a bit of debate over how to spell the new term and they are sometimes called #doortraits or #isolationportraits.

Many of the images are whimsical, poking fun where they can. One family poses on their porch with rolls of toilet paper around their wrists; even the dog gets one around its paw. Others dress up in costumes or party attire, taking a break from the stress and worry that the coronavirus pandemic has unleashed around the world.

Other photos are more stark, revealing the stillness and solitude of the social-distance era. And even today, in the midst of it, it’s easy to see that these collections, growing across North America and Europe, could easily hang on museum walls the way exhibits of stoic settlers of the Dust Bowl or cities in the Great Depression do a century later.

“These are really interesting documents at this time,” says Carol Payne, a professor of the history and theory of photography at Carleton University in Ottawa. While many of the journalistic photographs of the era revolve around barriers – adults separated from elderly parents in nursing homes, or isolated healthcare workers who can only see their children through windows – “porchraits” give subjects a sense of agency, she says, and in the end will show how ordinary people coped together.

“They are telling their future selves what it was like to live through what is really an historic crisis,” Professor Payne says. “People are writing their own social histories visually, not the history of politicians and nation-states but the history of individual people and how they got through it.”

Many of the photographers, like Mr. McRitchie, aren’t making money from it. If families can, he is encouraging them to donate to a local food bank. “It’s really just trying to take a moment of difficulty, and turning it into something positive,” he says, “and see if it can be replicated and grown into something bigger.”

Jon Neufeld’s family is the one outside the glass door last week in their residential community in Calgary. He says they were “hamming it up,” just having a bit of fun about being stuck inside all day. It also happened to be the day they were supposed to have their daughter’s 5th birthday party. Instead, she dressed up in pink and they ate birthday cake on the front steps (Mr. McRitchie was invited, one of four “front porch birthday parties” he’d celebrated that week).

Mr. Neufeld says it’s been fun to see the other portraits posted around social media. But collectively it tells a deeper tale. “The kind of struggle is implicit in the fact that if you look through the collection, we’re all on our porches. We’re all on the front steps of our houses,” he says, “where we are spending 99% of our time.”

That’s posed technical problems for photographers, who are more used to scenic backgrounds or studios where lighting possibilities are limitless. But through this work, Mr. McRitchie says he has documented something new: a family togetherness and a return to slower living. When he arrived at one house, two little children were sitting at their front window with a “campfire” they made from cardboard. They were pretending to roast marshmallows.

In between his shoots he’s noticed more teens out walking with their parents.

“That’s weird, right?” he says. “Before, mom or dad would go for a walk, and ask, ‘you guys want to come?’ And the kids are like, ‘no, not a chance.’ But now they’re out together.”

“It’s just so easy to be occupied with the negativity right now, and any break from that in a positive way is uplifting,” he continues. “When we see people are celebrating, laughing and having fun, and families that are together, it’s reminding us of the strength we can find together.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

The Explainer

Hot commodity: How toilet paper became an icon of stability

Mundane things can take on new meaning during times of crisis. In an uncertain time, toilet paper has taken on outsize proportions as something of an anchor, a marker of personal and societal stability.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

As stay-at-home guidelines swept the nation last month, rolls of toilet paper flew off the shelves while people contemplated what they didn’t want to run out of. Now bath tissue is one of the most sought-after products.

Although toilet paper may not be immediately available in retail stores or on Amazon, that doesn’t mean that all the toilet paper is gone. Shipments are still coming into stores regularly.

To address the shortage, many retailers have set limits on how much an individual shopper can purchase at a time. With office buildings largely closed, suppliers are also working to divert supplies meant for public bathrooms to residential customers.

Why is it we hoard toilet paper in times of crisis?

It might have something to do with a sense of cultural shame and privacy around toileting, says Richard Smyth, who has written a book on the history of toilet paper. But more than that, he says, “To a lot of people in the West, it stands for civilization.”

Hot commodity: How toilet paper became an icon of stability

The rush on toilet paper has provided ample comedic fodder to lighten the mood as fear around the novel coronavirus swirls. References to a toilet paper shortage have cropped up in countless memes, social media stand-up routines, and even pickup lines on dating apps. But it arises from a very real concern among consumers. For many, this bathroom staple has taken on outsize proportions as something of an anchor, a marker of personal and societal stability.

As stay-at-home guidelines swept the nation last month, rolls of bath tissue flew off the shelves while people contemplated what they didn’t want to run out of. The sudden surge in demand for toilet paper has raised questions about why we value toilet paper so much – and what its future in our lives might look like.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Where has all the toilet paper gone?

Although toilet paper may not be immediately available in retail stores or on Amazon, that doesn’t mean that all the toilet paper is gone. Shipments are still coming into stores regularly.

Unlike other consumer products in high demand right now, toilet paper is mostly produced domestically in the United States. And Procter & Gamble, for example, has said production at U.S. plants is at a record high.

The tricky part for suppliers, however, is that while demand for toilet paper is high now, it is likely to plummet to extremely low levels soon, as consumers work their way through the piles of toilet paper now residing in closets, basements, and garages.

Typically the demand for toilet paper rises in step with population growth, and in the long term that is unlikely to change. The respiratory symptoms associated with COVID-19 don’t typically call for increased usage of toilet paper. So companies are working to balance the need to meet current demand without creating a massive surplus down the line.

To mitigate this problem, many retailers have set limits on how much an individual shopper can purchase at a time. With office buildings largely closed, suppliers are also working to divert supplies meant for public bathrooms to residential customers.

How did toilet paper become essential?

Although toilet paper is largely considered a necessity across Western societies today, that hasn’t always been the case. In fact, it didn’t catch on right away.

Before a consumer product was designed for the task, humans used a variety of other items including leaves, moss, rocks, and corn cobs. The Romans had a sponge on a stick available in their communal lavatories.

As modern paper goods spread across the globe in the 19th century, people began ripping pages out of newspapers or catalogues. Then, in 1857, a New York businessman designed a paper product specifically for lavatory use.

It was initially considered a “quack product,” says Richard Smyth, author of “Bum Fodder: An Absorbing History of Toilet Paper.” Most Americans still used outhouses, and there wasn’t a place in the market for toilet paper. But as consumerism rose and indoor flush toilets became the norm, toilet paper became omnipresent.

Why do we hoard toilet paper in times of crisis?

This actually isn’t the first time that there has been this kind of a rush on toilet paper. In 1973, in the wake of a stock market crash, a rumor that there was a shortage prompted millions of American shoppers to begin hoarding toilet paper.

There wasn’t actually a shortage when it all began. But, much like bare shop shelves today, the suggestion alone that one might be forced to go without toilet paper triggered a buying spree that created a shortage.

But why toilet paper?

It might have something to do with a sense of cultural shame and privacy around toileting, Mr. Smyth says. “I think people see it as rock bottom. If you’re going to the toilet and you don’t have toilet paper, that’s the lowest you can go.”

Furthermore, Mr. Smyth adds, decades of marketing has contributed to this sense that toilet paper is essential to life as we know it. “To a lot of people in the West, it stands for civilization.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

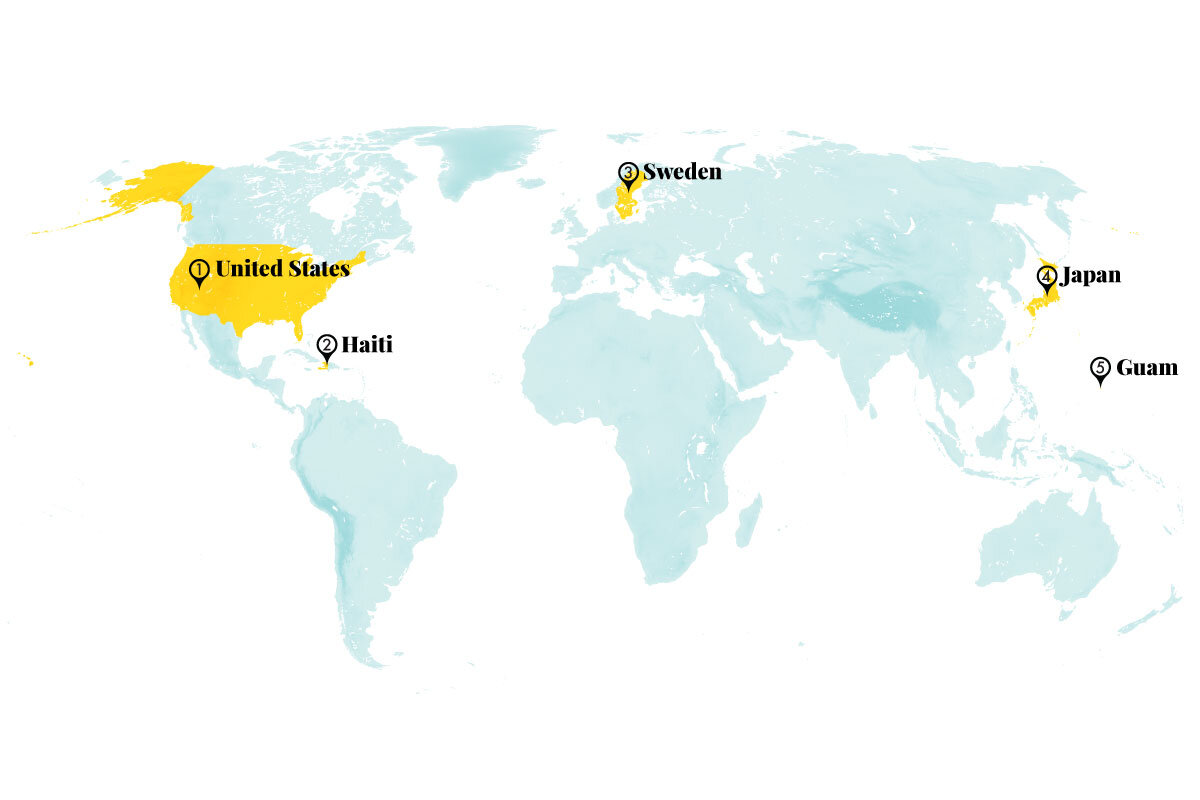

Points of Progress

Where one epidemic is in retreat

From an unconventional method to get a Mars rover moving again to the first Native American-owned studio in Hollywood’s history, here is our weekly roundup of positive stories to inspire you.

Where one epidemic is in retreat

1. United States

The Tesuque Pueblo tribe of New Mexico has repurposed a 75,000-square-foot casino into the first movie studio owned by a Native American tribe in the history of Hollywood. New Mexico has seen an exponential spike in filming to the point that Netflix has made Albuquerque its U.S. production hub. The Pueblo of Tesuque Development Corp. has invested $50 million in building out the new facility. The opening of the Camel Rock Studios will provide economic opportunities for the community, increase Native American representation in the film industry, and potentially establish internships and mentorships for the next generation of Native American filmmakers. (Variety)

2. Haiti

No new cases of cholera have been confirmed in more than 12 months in Haiti, indicating the decadelong epidemic appears to be over. The progress is credited to the fearless and formidable work of the Haitian health workers. Infecting 10% of the total population and killing 10,000 people, the cholera outbreak challenged a health care system dilapidated in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquakes. Although the early cases can be traced back to a United Nations base in Haiti that was flowing human waste into a river, it was the innovative efforts of the Haitian rapid response teams and health workers – not international organizations – that stabilized the outbreak. Experts say two more years must pass in order to definitively declare Haiti cholera-free. (The Guardian)

3. Sweden

One of five national pension funds in Sweden has committed to divesting all holdings in fossil fuel companies. As concerns over global climate change intensify, more Western funds are withdrawing from industries and companies responsible for emissions of carbon dioxide. At the close of 2019, pension fund AP1 held assets worth 4.5 billion Swedish crowns ($436 million) in fossil fuel companies. But the company announced it has already sold the larger part of these holdings, and plans to reach a “carbon-neutral portfolio” by 2050. AP1 joins a strategic shift among global money managers to comply with the United Nations Paris Agreement on climate change. (Reuters)

4. Japan

At the Tokyo Olympics, women are projected to make up almost half the field for the first time, the International Olympic Committee announced. The percentage of female athletes now competing in 2021 is expected to rise to nearly 49% – from 34% in 1996. In an effort to push for equal gender representation, the IOC also announced balanced gender representation across all 206 teams and that it will change its rules to allow one male and one female athlete to jointly carry their nation’s flag during the opening ceremony. For now this has to wait. On March 24, the IOC postponed the 2020 Olympics to a date no later than summer 2021, due to concerns about the coronavirus pandemic. The organization aims to reach full gender parity by the 2024 Olympics in Paris. (Reuters)

5. Guam

After decades of lobbying for reparations, more than 3,000 native islanders on Guam are expecting to receive overdue compensation from the U.S. government. U.S. forces heavily bombed Guam to recapture it from the Japanese during World War II. Recipients of the reparations report mixed feelings as they remember family and friends who were among the 1,100 islanders estimated to have died during Japan’s nearly three-year occupation of the U.S. territory. The newly opened war claims office is the culmination of years of political efforts by Guam’s nonvoting U.S. House delegates to persuade Congress to approve the reparations. (The Associated Press)

Mars

After its digging probe was stuck on the surface of Mars for over a year, NASA scientists finally figured out a way to get it back to work. It turns out the machine just needed a friendly whack from its own shovel. InSight has the task of mining the red planet’s soil to track temperature variations. But a few months after the probe landed in November 2018 it ran into a problem: The soil was too thick. With no one around to give it a shove, scientists had to improvise. Using a small shovel-like scoop on the end of InSight’s robotic arm, they commanded InSight to give itself a gentle nudge. Early data suggest it seems to have worked, but scientists are awaiting more data before they breathe a sigh of relief. (Popular Science)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Care for the social ills of isolation

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

As the COVID-19 shutdown of businesses goes global, governments are helping people deal with the hardship of lost jobs and wages. Yet they are discovering another need among people enduring prolonged isolation: problem behaviors that result in harm to others or themselves. For that, money is not a solution. Compassionate care is.

For many people, isolation at home combined with anxiety over COVID-19 has intensified existing personal problems, from addiction to bumpy relationships. Close to half of Americans told pollsters that the pandemic had affected their mental health.

The inner life of the isolated billions around the world now has an outer dimension. Many religious groups, therapists, and social activists are stepping up their outreach. Alcoholics Anonymous, for example, is holding meetings online or over the phone.

Most countries have the tools, such as the internet, to offer remote care and companionship for people cooped up at home and either physically alone or with someone who is abusive. The healing professions are helping people cope with fear of the virus. Others can help heal the emotions driving problem behaviors at home.

Care for the social ills of isolation

As the COVID-19 shutdown of businesses goes global, governments are helping people deal with the hardship of lost jobs and wages. Yet they are discovering another need among people enduring prolonged isolation: problem behaviors that result in harm to others or themselves.

For that, money is not a solution. Compassionate care is.

Spain, for example, has restricted most gambling advertising because of a spike in online gaming among people stuck at home and either lonely, bored, or stressed.

In many countries, hotlines for reporting domestic abuse have had to increase the number of social workers.

And with China disclosing a jump in divorces after ending its coronavirus lockdown, Russia decided to suspend the registration of divorces until June 1. Russians already have one of the world’s highest divorce rates.

For many people, isolation at home combined with anxiety over COVID-19 has intensified existing personal problems, from addiction to bumpy relationships. Close to half of Americans told pollsters for the Kaiser Family Foundation that the pandemic had affected their mental health.

The inner life of the isolated billions around the world now has an outer dimension. Many religious groups, therapists, and social activists are stepping up their outreach. Alcoholics Anonymous, for example, is holding meetings online or over the phone. Governments, meanwhile, are only catching up with the problem.

In Britain, a few members of Parliament have asked the gambling industry to help reduce the sudden increase in online wagering following the shutdown of brick-and-mortar gaming sites. They want caps on how much money a person can bet each day, for example, and an end to inducements to risk money on off-beat contests like table tennis in the absence of mainstream sports. An estimated 9% of online bettors in Britain are considered problem gamblers. The industry has responded by promising to “monitor the amount of time and money that players spend during the pandemic lockdown.”

Perhaps the term self-isolation needs to be dropped for something less self-oriented. Most countries have the tools, such as the internet, to offer remote care and companionship for people cooped up at home and either physically alone or with someone who is abusive. The healing professions are helping people cope with fear of the virus. Others can help heal the emotions driving problem behaviors at home.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Generosity that goes both ways

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Amy Richmond

In the face of employment uncertainty and economic volatility, meeting one’s own needs – much less helping others with theirs – can seem nearly impossible. But recognizing God as the source of limitless good empowers us to experience and share divine goodness in tangible ways.

Generosity that goes both ways

I braced myself as I watched a “60 Minutes” news segment called “Coronavirus and the economy: Best and worst-case scenarios from Minneapolis Fed president.” The interview was with Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. In the interview, Mr. Kashkari – who helped lift the U.S. out of 2008’s Great Recession – indicated that he’d learned, after the fact, that it’s better to err on the side of being generous rather than singling out some as deserving and others as not.

I love the idea of a connection between generosity and widespread benefits. While it may seem like a counterintuitive pairing on the surface, it coincides with what Christian Science refers to as God’s law of Love. Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, spent years studying the Holy Bible and learned about the expansive and loving nature of God. In fact, Love itself is a biblical name for God (see I John 4:16).

Mrs. Eddy was referring to God as divine Love when she wrote this in her book, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “Love is impartial and universal in its adaptation and bestowals. It is the open fount which cries, ‘Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters’” (p. 13). God is generously giving unlimited good to every one of us as God’s beloved children, the spiritual expression of divine Love – all the time.

I know it doesn’t always seem like it, especially these days with layoffs and greatly diminished retirement savings. But the spiritual fact of God’s goodness remains unchanged, and Mrs. Eddy – following in the path Jesus pointed out – proved this over and over, and we can experience evidence of divine good in our lives, too.

One of my favorite examples along these lines involved a farmer and his cows. There hadn’t been enough rain in the area, the farmer’s well was empty, and the cows were starting to go dry. When Mrs. Eddy learned of this, she said, “Oh! if he only knew, Love fills that well.” And the next morning the well was full, even though it hadn’t rained for days (see Yvonne Caché von Fettweis and Robert Townsend Warneck, “Mary Baker Eddy: Christian Healer,” Amplified Edition, p. 177).

Each of us, too, can experience how that same Love fills whatever empty well we seem to be facing. God doesn’t give “just enough,” but gives generously – and so we can express Love-impelled generosity toward others.

Once, right before I dropped a significant amount of weight, I purchased a two-piece suit. I needed it for work, and it was expensive! But I wore the suit only once or twice before it no longer fit and was too big to get altered.

I’d been praying a lot about some profound losses in my life, which had led to a sweet conviction of God’s abundant provision for all His children, me included. So when I met a woman who’d just started a new job and didn’t have the proper clothing for it, I offered her my suit. When she gratefully accepted, I honestly didn’t feel as though I was losing anything, even though some might say I’d wasted a chunk of money. I guess I was erring on the side of generosity.

That very same night, as I was walking into my apartment building, I ran into a neighbor. Guess what she gave me, with no prompting? A three-piece designer suit well out of my budget range. I loved it, and it fit perfectly!

My story is just one small example of how understanding God as the source of all good frees us up to be generous, and opens the door for us to see more evidence of that good in our lives. Sometimes it’s in small ways, other times larger ones. But whether the need relates to your “well,” mine, or someone else’s across the globe, God’s limitless giving is here to benefit us all.

A message of love

Call to prayer

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Come back on Monday, when Lenora Chu looks at how a chronic shortage of health care workers has dogged developed nations – and how the U.S. and Germany have addressed the problem.