Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

David Clark Scott

David Clark Scott

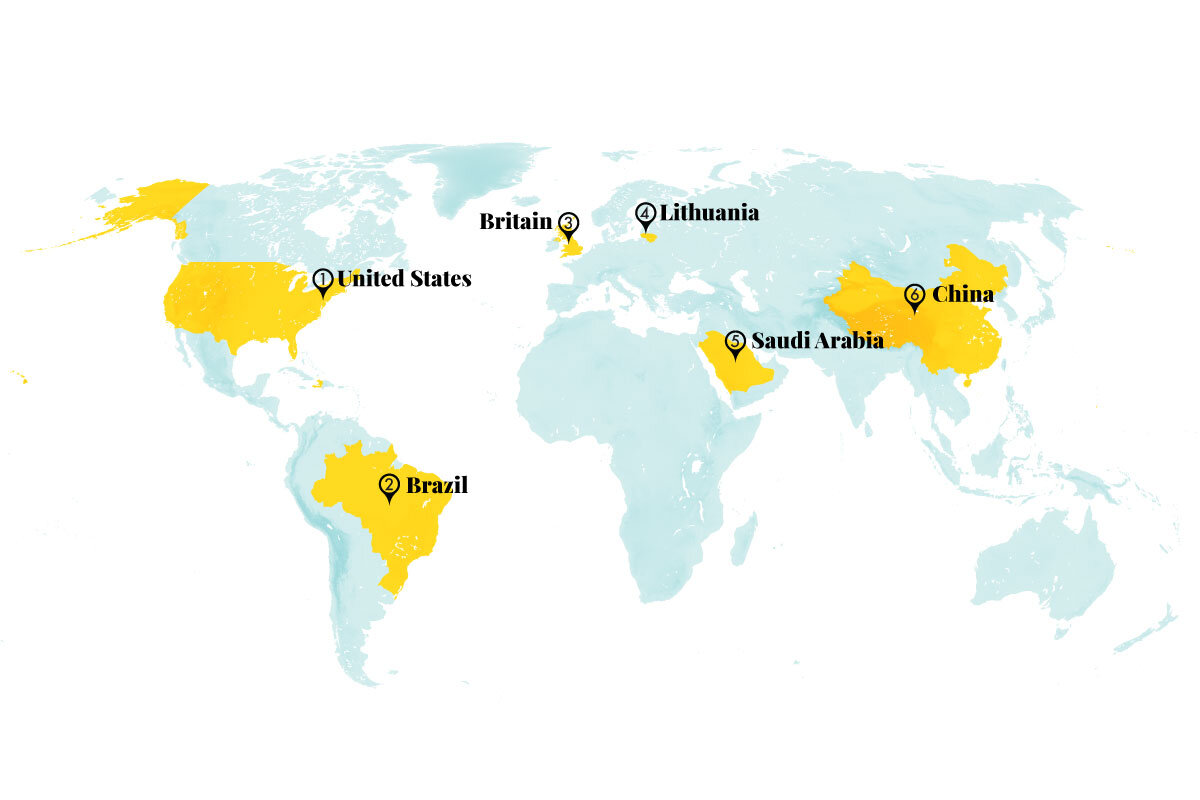

Today’s five selected stories include bridging the U.S. gap between digital haves and have-nots, leadership models in a pandemic, India’s quest for community in a lockdown, new ways to measure high school success, and our global points of progress report.

In American space lore, the Apollo 13 lunar mission has become synonymous with near-disaster – and innovation in a crisis.

After their spacecraft malfunctioned, the three astronauts jumped into their "lifeboat," the lunar module. You’ll recall there was enough air for only two of the three NASA astronauts to survive the journey home. But engineers on Earth helped the astronauts build a jury-rigged CO2 filter system with paper covers from manuals, duct tape, and a few other items on board.

I bring this up because Saturday is the 50th anniversary of that mission, and we are today collectively living through an Apollo 13 moment.

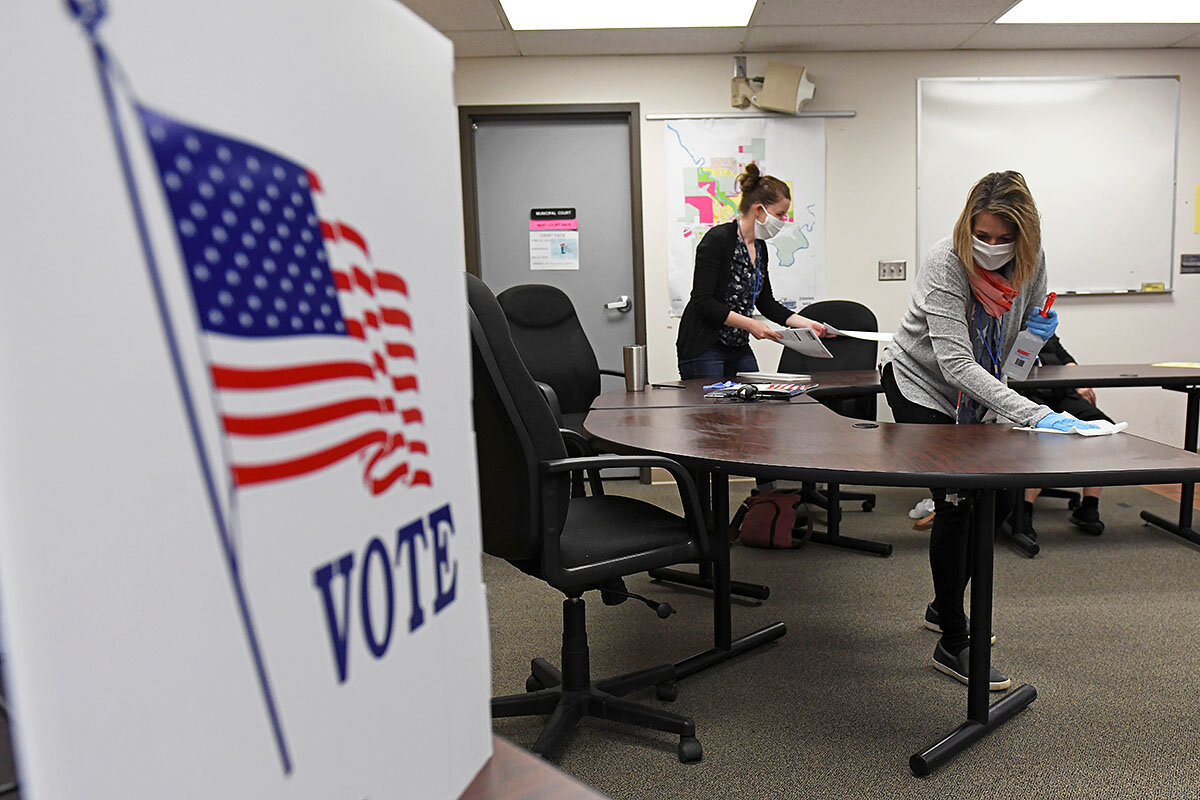

To paraphrase astronaut Jack Swigert, “Humanity, we have a problem.” And around the world, people are responding to the pandemic with all the verve and creativity of NASA engineers. Government bureaucracies are displaying uncharacteristic flexibility and responsiveness to save lives and economies. Rivals are working side by side. Parents are devising ingenious ways to work with children at home. Businesses are experimenting with new ways to deliver goods and services while social distancing.

But will all this duct tape hold?

Perhaps you’ll also recall one of the best lines from the 1995 film “Apollo 13.” Flight Director Gene Kranz (played by Ed Harris) overhears a NASA director say, “This could be the worst disaster NASA has ever experienced.”

“With all due respect, sir,” Mr. Kranz interjects, “I believe this is going to be our finest hour.”